Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

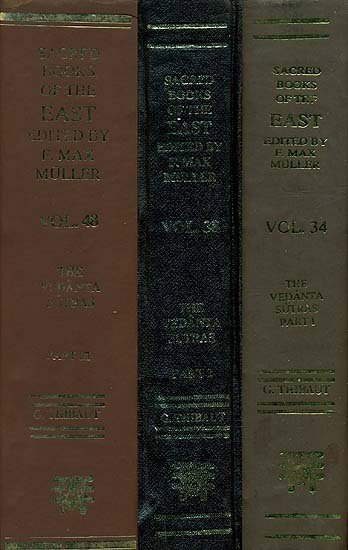

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Summary statement as to the way in which different scriptural texts are to reconciled

Summary statement as to the way in which different scriptural texts are to reconciled.

The whole matter may be summarily stated as follows. Some texts declare a distinction of nature between non-intelligent matter, intelligent beings, and Brahman, in so far as matter is the object of enjoyment, the souls the enjoying subjects, and Brahman the ruling principle. 'From that the Lord of Māyā creates all this; in that the other one is bound up through that Māyā' (Śvet. Up. IV, 9); 'Know Prakṛti to be Māyā, and the great Lord the ruler of Māyā' (10); 'What is perishable is the Pradhāna, the immortal and imperishable is Hara: the one God rules the Perishable and the Self' (Śvet Up. I, 10)—In this last passage the clause'the immortal and imperishable is Hara,' refers to the enjoying individual soul, which is called 'Hara,' because it draws (harati) towards itself the pradhāna as the object of its enjoyment.—' He is the cause, the lord of the lords of the organs, and there is of him neither parent nor lord' (Śvet. Up. VI, 9); 'The master of the pradhāna and of the individual souls' (Śvet. Up. VI, 16); 'The ruler of all, the lord of the Selfs, the eternal, blessed, undecaying one' (Mahānār. Up. XI, 3); 'There are two unborn ones, one knowing, the other not knowing, one a ruler, the other not a ruler' (Śvet. Up. 1, 9); 'The eternal among the non-eternal, the intelligent one among the intelligent, who though one fulfils the desires of many' (Śvet. Up. VI, 13); 'Knowing the enjoyer, the object of enjoyment and the Mover' (Śvet. Up. I, 12); 'One of them eats the sweet fruit, the other looks on without eating' (Śvet. Up. IV, 6); 'Thinking that the Self is different from the Mover, blessed by him he reaches Immortality' (Śvet. Up. I, 6); 'There is one unborn female being, red, white, and black, uniform but producing manifold offspring. There is one unborn male being who loves her and lies by her; there is another who leaves her after he has enjoyed her' (Śvet. Up. IV, 5). 'On the same tree man, immersed, bewildered, grieves on account of his impotence; but when he sees the other Lord contented and knows his glory, then his grief passes away' (Śvet. Up. IV, 9).—Smṛti expresses itself similarly.—'Thus eightfold is my nature divided. Lower is this Nature; other than this and higher know that Nature of mine which constitutes the individual soul, by which this world is supported' (Bha. Gì. VII, 4, 5). 'All beings at the end of a Kalpa return into my Nature, and again at the beginning of a Kalpa do I send them forth. Resting on my own Nature again and again do I send forth this entire body of beings, which has no power of its own.

being subject to the power of nature' (Bha. Gī. IX, 7, 8); 'With me as supervisor Nature brings forth the movable and the immovable, and for this reason the world ever moves round' (Bha. Gī. IX, 10}; 'Know thou both Nature and the Soul to be without beginning' (XIII, 19); 'The great Brahman is my womb, in which I place the embryo, and thence there is the origin of all beings' (XIV, 3). This last passage means—the womb of the world is the great Brahman, i.e. non-intelligent matter in its subtle state, commonly called Prakṛti; with this I connect the embryo, i.e. the intelligent principle. From this contact of the non-intelligent and the intelligent, due to my will, there ensues the origination of all beings from gods down to lifeless things.

Non-intelligent matter and intelligent beings—holding the relative positions of objects of enjoyment and enjoying subjects, and appearing in multifarious forms—other scriptural texts declare to be permanently connected with the highest Person in so far as they constitute his body, and thus are controlled by him; the highest Person thus constituting their Self. Compare the following passages: 'He who dwells in the earth and within the earth, whom the earth does not know, whose body the earth is, and who rules the earth within, he is thy Self, the ruler within, the immortal,' etc. (Bṛ. Up. III, 7, 3-23); 'He who moves within the earth, whose body the earth is, etc.; he who moves within death, whose body death is,' etc.(Subāla Up. VII, 1). In this latter passage the word 'death' denotes what is also called 'darkness,' viz. non-intelligent matter in its subtle state; as appears from another passage in the same Upanishad,'the Imperishable is merged in darkness.' And compare also 'Entered within, the ruler of creatures, the Self of all' (Taitt. Ār. III, 24).

Other texts, again, aim at teaching that the highest Self to whom non-intelligent and intelligent beings stand in the relation of body, and hence of modes, subsists in the form of the world, in its causal as well as in its effected aspect, and hence speak of the world in this its double aspect as that which is (the Real); so e.g. 'Being only this was in the beginning, one only without a second—it desired, may I be many, may I grow forth—it sent forth fire,' etc., up to 'all these creatures have their root in that which is,' etc., up to 'that art thou, O Śvetaketu' (Ch. Up. VI, 2-8); 'He wished, may I be many,' etc., up to 'it became the true and the untrue' (Taitt. Up. II, 6). These sections also refer to the essential distinction of nature between non-intelligent matter, intelligent beings, and the highest Self which is established by other scriptural texts; so in the Chāndogya passage, 'Let me enter those three divine beings with this living Self, and let me then evolve names and forms'; and in the Taitt. passage, 'Having sent forth that he entered into it; having entered it he became sat and tyat, knowledge and (what is) without knowledge, the true and the untrue,' etc. These two passages evidently have the same purport, and hence the soul’s having its Self in Brahman—which view is implied in the Kh. passage—must be understood as resting thereon that the souls (together, with matter) constitute the body of Brahman as asserted in the Taitt. passage ('it became knowledge and that which is without knowledge,' i.e. souls and matter). The same process of evolution of names and forms is described elsewhere also, 'All this was then unevolved; it became evolved by form and name' (Bṛ. Up. I, 4, 7). The fact is that the highest Self is in its causal or in its 'effected' condition, according as it has for its body intelligent and non-intelligent beings either in their subtle or their gross state; the effect, then, being non-different from the cause, and hence being cognised through the cognition of the cause, the result is that the desired 'cognition of all things through one' can on our view be well established. In the clause 'I will enter into these three divine beings with this living Self,' etc., the term 'the three divine beings' denotes the entire aggregate of non-sentient matter, and as the text declares that the highest Self evolved names and forms by entering into matter by means of the living souls of which he is the Self, it follows that all terms whatsoever denote the highest Self as qualified by individual Selfs, the latter again being qualified by non-sentient matter. A term which denotes the highest Self in its causal condition may therefore be exhibited in co-ordination with another term denoting the highest Self in its 'effected' state, both terms being used in their primary senses. Brahman, having for its modes intelligent and non-intelligent things in their gross and subtle states, thus constitutes effect and cause, and the world thus has Brahman for its material cause (upādāna). Nor does this give rise to any confusion of the essential constituent elements of the great aggregate of things. Of some parti-coloured piece of cloth the material cause is threads white, red, black, etc.; all the same, each definite spot of the cloth is connected with one colour only white e.g., and thus there is no confusion of colours even in the 'effected' condition of the cloth. Analogously the combination of non-sentient matter, sentient beings, and the Lord constitutes the material cause of the world, but this does not imply any confusion of the essential characteristics of enjoying souls, objects of enjoyment, and the universal ruler, even in the world’s 'effected' state. There is indeed a difference between the two cases, in so far as the threads are capable of existing apart from one another, and are only occasionally combined according to the volition of men, so that the web sometimes exists in its causal, sometimes in its effected state; while non-sentient matter and sentient beings in all their states form the body of the highest Self, and thus have a being only as the modes of that—on which account the highest Self may, in all cases, be denoted by any term whatsoever. But the two cases are analogous, in so far as there persists a distinction and absence of all confusion, on the part of the constituent elements of the aggregate. This being thus, it follows that the highest Brahman, although entering into the 'effected' condition, remains unchanged—for its essential nature does not become different—and we also understand what constitutes its 'effected' condition, viz. its abiding as the Self of non-intelligent and intelligent beings in their gross condition, distinguished by name and form. For becoming an effect means entering into another state of being.

Those texts, again, which speak of Brahman as devoid of qualities, explain themselves on the ground of Brahman being free from all touch of evil. For the passage, Ch. Up. VIII, 1, 5—which at first negatives all evil qualities 'free from sin, from old age, from death, from grief, from hunger and thirst', and after that affirms auspicious qualities 'whose wishes and purposes come true'—enables us to decide that in other places also the general denial of qualities really refers to evil qualities only.—Passages which declare knowledge to constitute the essential nature of Brahman explain themselves on the ground that of Brahman—which is all-knowing, all-powerful, antagonistic to all evil, a mass of auspicious qualities—the essential nature can be defined as knowledge (intelligence) only—which also follows from the 'self-luminousness' predicated of it. Texts, on the other hand, such as 'He who is all-knowing' (Mu. Up. I, 1, 9); 'His high power is revealed as manifold, as essential, acting as force and knowledge' (Śvet. Up. VI, 8);; 'Whereby should he know the knower' (Bṛ. Up. II, 4, 14), teach the highest Self to be a knowing subject. Other texts, again, such as 'The True, knowledge, infinite is Brahman' (Taitt. Up. II, 1, 1), declare knowledge to constitute its nature, as it can be denned through knowledge only, and is self-luminous. And texts such as 'He desired, may I be many' (Taitt. Up. II, 6); 'It thought, may I be many; it evolved itself through name and form' (Ch. Up. VI, 2), teach that Brahman, through its mere wish, appears in manifold modes. Other texts, again, negative the opposite view, viz. that there is a plurality of things not having their Self in Brahman. 'From death to death goes he who sees here any plurality'; 'There is here not any plurality' (Bṛ. Up. IV, 4, 19); 'For where there is duality as it were' (Bṛ. Up. II, 4, 14). But these texts in no way negative that plurality of modes—declared in passages such as 'May I be many, may I 'grow forth'—which springs from Brahman’s will, and appears in the distinction of names and forms. This is proved by clauses in those 'negativing' texts themselves, 'Whosoever looks for anything elsewhere than in the Self', 'from that great Being there has been breathed forth the Ṛg-veda,' etc. (Bṛ. Up. II, 4, 6, 10).— On this method of interpretation we find that the texts declaring the essential distinction and separation of non-sentient matter, sentient beings, and the Lord, and those declaring him to be the cause and the world to be the effect, and cause and effect to be identical, do not in any way conflict with other texts declaring that matter and souls form the body of the Lord, and that matter and souls in their causal condition are in a subtle state, not admitting of the distinction of names and forms while in their 'effected' gross state they are subject to that distinction. On the other hand, we do not see how there is any opening for theories maintaining the connexion of Brahman with Nescience, or distinctions in Brahman due to limiting adjuncts (upādhi)—such and similar doctrines rest on fallacious reasoning, and flatly contradict Scripture.

There is nothing contradictory in allowing that certain texts declare the essential distinction of matter, souls, and the Lord, and their mutual relation as modes and that to which the modes belong, and that other texts again represent them as standing in the relation of cause and effect, and teach cause and effect to be one. We may illustrate this by an analogous case from the Karmakāṇḍa. There six separate oblations to Agni, and so on, are enjoined by separate so-called originative injunctions; these are thereupon combined into two groups (viz. the new moon and the full-moon sacrifices) by a double clause referring to those groups, and finally a so-called injunction of qualification enjoins the entire sacrifice as something to be performed by persons entertaining a certain wish. In a similar way certain Vedānta-texts give instruction about matter, souls, and the Lord as separate entities ('Perishable is the pradhāna, imperishable and immortal Hara,' etc., Śvet Up. I, 10; and others); then other texts teach that matter and souls in all their different states constitute tbc body of the highest Person, while the latter is their Self ('Whose body the earth is,' etc.); and finally another group of texts teaches—by means of words such as 'Being,' 'Brahman,' 'Self,' denoting the highest Self to which the body belongs—that the one highest Self in its causal and effected states comprises within itself the triad of entities which had been taught in separation ('Being only this was in the beginning'; 'In that all this has its Self; 'All this is Brahman').—That the highest Self with matter and souls for its body should be simply called the highest Self, is no more objectionable than that that particular form of Self which is invested with a human body should simply be spoken of as Self or soul—as when we say 'This is a happy soul.'