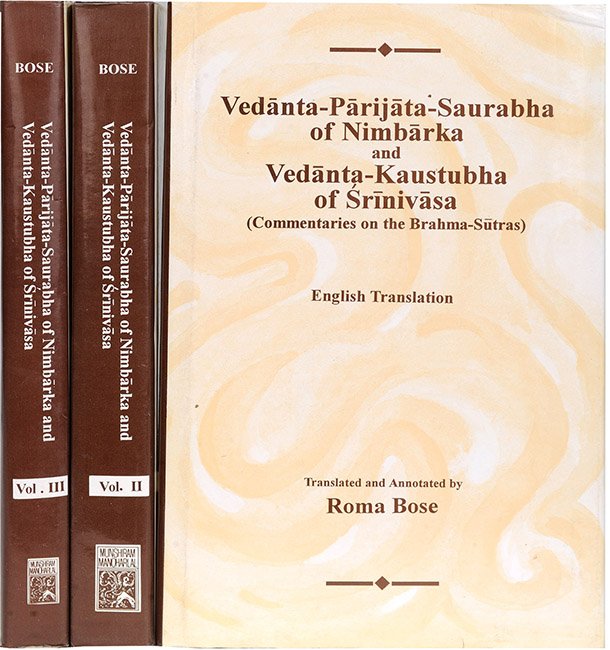

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 3.4.46, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 3.4.46

English of translation of Brahmasutra 3.4.46 by Roma Bose:

“(There is) injunction of another auxiliary for one who possesses that, as in the case of injunction and so on, (the term ‘mauna’ denoting), in accordance with the other alternative, a third something.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

In the text: “Hence let a Brāhmaṇa, being disgusted with learning, desire to live in the childlike state; being disgusted with the states of childhood and learning, then he becomes an ascetic” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.5.1[1]), the term ‘ascetic’ may, of course, mean ‘one possessed of knowledge’, yet “according to the other alternative”, it may also mean ‘one given to profound reflection’. Hence, “another auxiliary”, “a third” something as distinguished from learning and childlike state, viz. asceticism, has been enjoined here, like sacrifice and the rest and like calmness and the rest.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Previously, sacrifices and the rest and calmness and the rest have been determined as auxiliaries to one who is possessed of knowledge. Similarly, asceticism is another auxiliary to one possessed of knowledge. Now, a discussion relating to this is being undertaken.

In the Bṛhadāraṇyaka, to the question of Kahola, it is said: “Hence let a Brāhmaṇa, being disgusted with learning, desire to live in the childlike state; being disgusted with the states of childhood and learning, then he becomes an ascetic; being disgusted with the non-ascetic and ascetic states, then he becomes a Brāhmaṇa” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.5.1). Here the doubt is as to whether here like the states of childhood and learning, asceticism too is enjoined, or is only referred back (as something already enjoined). If it be suggested that ‘asceticism’ means knowledge, and that has indeed been already established by the phrase: ‘Being disgusted with learning’, and (hence) the word ‘ascetic’ simply refers back to this,—

We reply: “For one who is possessed of that”, i.e. for one possessed of knowledge, “a third”, i.e. a means, viz. asceticism, a third something as distinguished from learning and childlike state, is enjoined. This very thing the author states in the phrase: “An injunction of another auxiliary”. The states of learning and childhood are auxiliaries to a direct vision of Brahman, the object to be attained; asceticism is another auxiliary as distinguished from them; and the word ‘ascetic’ is nothing but an injunction with regard to it. “As in the ease of injunction and so on.” An injunction is what is enjoined as helpful, such as, all the duties incumbent on the stages of life, sacrifice, charity and so on, and calmness and the rest. By the words “and so on” the states of learning and childhood are understood.

To the argument, viz. that ‘asceticism’ means knowledge, and that has indeed already been established by the phrase: ‘Being disgusted with learning’, and hence the word ‘ascetic refers back to this,—we reply: “In accordance with the other alternative”. That is, since the word ‘ascetic’ is well known to mean, alternately, ‘one given to profound reflection’, as in the statement “Among ascetics also, I am Vyāsa” (Gītā 10.37) ‘asceticism’ is a different thing, a third something, distinguished from the state of learning. Here although in the phrase: ‘Then an ascetic’, there is no employment of the imperative, yet this special kind of reflection, not enjoined before, must be taken as something to be enjoined. As in this way the previous Brāhmaṇas have attained their ends ‘so’ let another Brāhmaṇa too, ‘being disgusted with’, i.e. having succeeded with certainty, in ‘the state of learning’, i.e. the duties of a learned man, viz. hearing of the Veda, ‘desire to stay in the childlike state’, i.e. wish to stay reflecting. Having succeeded in both, he may be an ‘ascetic’, i.e. given to profound meditation. After that, having succeeded in non-asceticism, i.e. in the group of means other than asceticism, as well as ‘asceticism’, he becomes a ‘Brāhmaṇa’, i.e. comes to attain knowledge,—this is the meaning of the text.[2]

Comparative views of Baladeva:

He too begins a new adhikaraṇa here (one sūtra), but continues the topic of the nirapekṣa devotees. This is sūtra 47 in his commentary. Hence the sūtra: “(There is) the injunction of another third auxiliary (viz. meditation), an alternative (to hearing and thinking) for one who has that, (viz. for the nirapekṣa devotees), as in the case of injunction and so on”. That is, in the case of the svaniṣṭha and pariniṣṭha devotees, sacrifice and calmness, self-control and so on are enjoined as auxiliaries to knowledge. But the nirapekṣa devotees already possess these, and so in their case these two sets of auxiliaries cannot be enjoined. Hence in their case meditation is enjoined instead, and this they must practise necessarily, just as house-holders and the rest must necessarily perforin the saṃdhyā-ceremony and so on.[3]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Quoted by Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja, Bhāskara and Śrīkaṇṭha.

[2]:

I.e. here pāṇḍitya means: śravaṇa, bālya manana and mauna nididhyāsana.

[3]:

Govinda-bhāṣya 3.4.47, p. 293-294, Chap. 3.