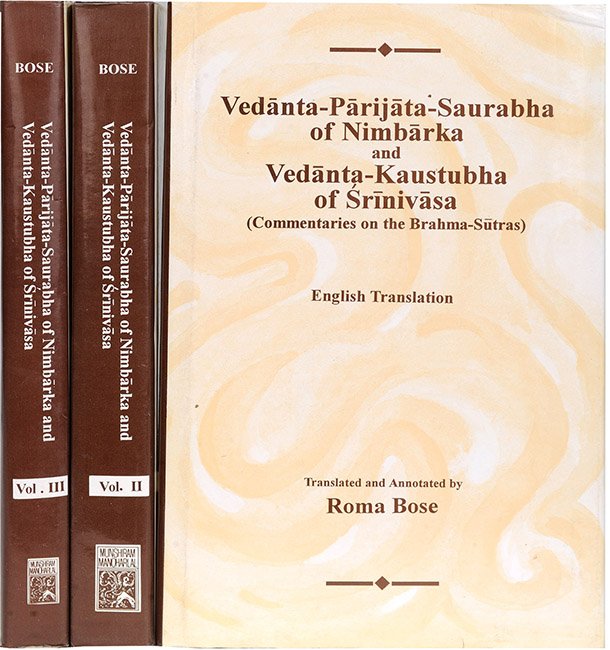

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 3.4.40, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 3.4.40

English of translation of Brahmasutra 3.4.40 by Roma Bose:

“But of one who has become that there is no becoming not that, (this is the view) of Jaimini too on account of restriction, on account of the absence of the forms of that.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

“But” the giving up of the state of chastity which one has reached is not allowed,—this the view of “Jaimini too”, on account of the absence of texts, on account of the absence of a cause, on account of the absence of good custom.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Now the problem is being considered, viz. whether those also who have fallen from the stage of a perpetual religious student bound by chastity and so on are entitled to knowledge or not.

It has been established above that there are such stages of life where chastity is obligatory. The doubt is as to whether those who have fallen from these are entitled to the knowledge of Brahman, or not. If it be suggested that like widowers and so on, they are so entitled, through the muttering of prayers and so on,—

We reply: The word “but” is meant for disposing of the objection. “Of one who has become that,” i.e. of one who has reached, as a supreme fruit, the stage where chastity is obligatory, there is “no becoming not that”, i.e. no falling off,—this is the view “of Jaimini too”. The word “too” indicates that the author’s own view is confirmed through being held by Jaimini as well. The sense is that it being impossible for a perpetual religious student bound by chastity[1], a hermit belonging to the third religious order[2] and a mendicant belonging to the fourth religious order[3] to stay outside a stage of life like widowers and the rest, they cannot be entitled to the knowledge of Brahman.

The author states the reasons why such a falling off is not allowable thus: “On account of restriction, on account of the absence of the forms of that”, that is, on account of the restriction with regard to the non-deviation from a stage of life, in the passages: A “student of sacred knowledge, dwelling in the house of a teacher, exhausting himself completely in the house of a teacher, is the third” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 2.23.1), “One should go to the forest, thence one should not return any more”. “Having once given up the fire, one should not return any more” (Kaṭha 5.4). The compound “on account of the absence of the forms of that” is to be explained as follows: The word “that” means ‘not becoming that’. The words “the forms” mean scriptural tests. Hence, the clause means: because of the absence of texts indicative of the falling from a stage of life. That means, there are no texts negativing the steady adherence to a stage of life. By the plural (in “abhāvebhyaḥ”) other kinds of absence are to be understood, viz. on account of the absence of texts indicative of descent (from a higher stage), unlike the texts indicative of ascent (to a higher stage), such as; “Having completed the life of a religious student, let one become a house-holder; having become a house-holder let one become a dweller in the forest; having become a dweller in the forest, let one wander forth” (Jābāla 4); on account of the absence of any cause for such a falling off; and on account of the absence of good custom.

Comparative views of Śaṅkara:

Reading slightly different, viz. “niyamātad rūpābhāvebhyaḥ”.[4]

Comparative views of Bhāskara:

Reading slightly different, viz. “Jaimini” instead of “Jaimineḥ”.[5]

Comparative views of Baladeva:

Reading like Śaṅkara’s. Interpretation different, viz. “But one who has become that (viz. a nirapekṣa), there is no becoming not that, (this is the view) of Jaimini too, on account of the restriction (viz. that the senses of the nirapekṣa devotee are devoted to the Lord alone and never to worldly objects), on account of the want of desire (for anything other than Brahman), and on account of the absence (of the life of a house-holder)”. That is, a nirapekṣa devotee never deviates from his vow and enters worldly life.[6]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Naiṣṭhika.

[2]:

Vaikhānasa.

[3]:

Parivrājaka.

[4]:

Brahma-sūtras (Śaṅkara’s commentary) 3.4.40, p. 885.

[5]:

Brahma-sūtras (Bhāskara’s Commentary) 3.4.39, (written as 3.4.40), p. 213.

[6]:

Govinda-bhāṣya 3.4.40, pp. 283-284, Chap. 3.