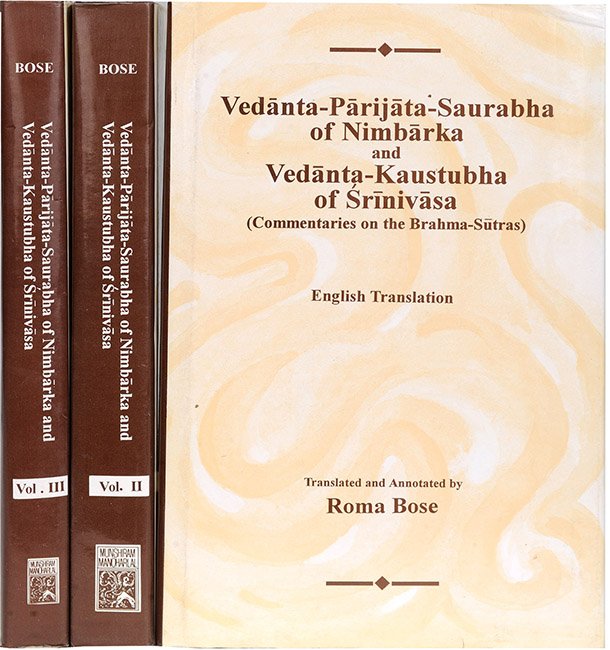

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 3.3.26, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 3.3.26

English of translation of Brahmasutra 3.3.26 by Roma Bose:

but in the abandonment (of merit and demerit, the taking of them by others is to be supplied) on account of the word ‘taking’ being supplementary (to the word ‘abandoning’), as in the case of kuśa, metre, praise, and accompanying song, it has been said (in pūrva-mīmāṃsā).”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

In the abandonment,” consisting in getting rid of merits and demerits, stated in the scriptural passage: “Then the knower, having discarded merits and demerits” (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 3.1.3[1]), the taking, consisting in taking the merits and demerits, discarded by the knower, stated in the passage: “His sons obtain the inheritance, his friends the good deeds, his enemies the bad deeds”,[2] is included. Why? Because the word ‘taking’, mentioned in another branch, is supplementary to the word ‘abandoning’, just as the text: “The progeny of the udumbara tree”[3] is supplementary to the text: “The kuśas are progeny of tree”; just as the text: “The metres of the gods are the prior” is supplementary to the text: “Let one praise by the metres”; just as the text: “The sun is half-risen” (Śat.Śrutyanta-suradruma 9.7.19[4]) is supplementary to the text: “He assists the chanting of the ṣoḍaśin[5] with gold[6]”, and just as the text: “The Adhvaryyu [Adhvaryu][7] does not[8] join the singing” (Taittirīya-saṃhitā 6.3.1[9]) is supplementary to the text: “The sacrificial priests join the singing”.[10] Moreover, it is said by Jaimini as well: “Let it be supplementary to the text, on account of the impropriety of an option” (Pūrva-mīmāṃsā-sūtra 10.8.15[11]).

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Now the author points out that the inclusion of a particular matter in a particular place, with which it is connected, stands to reason.

In the Upaniṣad of the Tāṇḍins, it is declared: “Shaking off evil, as a horse his hairs, shaking off the body as the moon frees itself from the mouth of Rāhu, I, with the self obtained, pass into the uncreated world of Brahman” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 8.13.1). Similarly, it is declared by the text of the followers of the Atharva-veda: “His sons obtain the inheritance, his friends the good deeds, his enemies the bad deeds”. The Śāṭyāyanins read: “Then he discards good and evil deeds. His dear relatives obtain the good deeds, those not dear the evil deeds” (Kauṣītaki-upaniṣad 1.4).

Now, in the Upaniṣad of the Tāṇḍins, as well as in the text of the followers of the Atharva-veda, the abandonment of merit and demerit is declared. In the text of the Śāṭyāyanins, the obtainment of merit and demerit by the dear and the not dear is declared. In the text of the Kauṣītakins, on the other hand, both are declared. This being the case, there is no room for any doubt in the case where both abandoning and taking are mentioned. Where there is the direct mention of taking only, there abandoning too is implied, since taking is impossible without (prior) abandoning.[12] But where only abandoning is mentioned, there the following (question) is to be considered: The doubt is as to whether the taking of the abandoned merit and demerit, which taking is mentioned elsewhere, is to be inserted in the Upaniṣad of the Tāṇḍins and in the text of the followers of the Atharva-veda, or not. On the suggestion, viz. It is not to be inserted owing to the force of separate mention. Otherwise, the double implication (viz. abandoning and taking)—which is the result of such an insertion—being already established in the cases of the two texts of the Tāṇḍins and the followers of the Atharva-veda through such an insertion from the text of the Kauṣītakins, the mention of abandoning in those two texts must become useless,[13]—

We reply: “But in the abandonment, on account of the word ‘taking’ being supplementary”. The word “but” disposes of the (above) prima facie view. “In the abandonment,” i.e. in the text which designates abandoning only, taking is to be inserted. Why? “On account of the word ‘taking’ being supplementary,” i.e. on account of the word ‘taking’ being supplementary to the word ‘abandoning’. The sense is that in the Upaniṣad of the Kauṣītakins, the text designating the taking of the good and evil deeds is recorded as being supplementary to the text designating the abandoning of the good and evil deeds. Similarly here too, it is essential that the merits and demerits, abandoned by a knower, should be obtained by others.

(The author) states a number of parallel instances, illustrating the fact that a text, mentioned in one branch, may form the supplement of a text, mentioned in another branch, thus: “As in the case of the kuśa, metre, praise and accompanying song”. Thus, just as it being known in a general manner that the kuśas are the progeny of, tree from the text of the Kauṣītakins, viz. “You kuṣas are the progeny of the tree, do protect me”, it is known from the specific text of the Śāṭyāyanins: “The progeny of the udumbara tree”, that the kuśas are the progeny of the udumbara tree,—this being so, the text of the Śāṭyāyanins becomes the supplement of the text of the Kauṣītakins,—the construction of this (latter) text is as follows: O Kuśas! You are the progeny of the tree, protect, i.e. save me, the sacrificer;—just as no specific order of priority and posteriority of gods and demons being mentioned in the text: “Let one praise by metres”, a specific order is known from the text of the Paiṅgins, viz. “The metres of the gods are prior”; just as on an enquiry into the time of chanting, which is a subsidiary part of the taking of a particular kind of pot, viz. ṣoḍaśin, the time not being known specifically from the text: “He assists the chanting of the ṣoḍaśin with gold”, the text of the Taittirīyas, designating the time specifically thus: “When the sun is half risen, he assists the chanting of the ṣoḍaśin” (Śat. Śrutyanta-suradruma 9.7.19) becomes the supplement of that text; and just as the prohibitive text of one branch, viz. “The Adhvaryyu [Adhvaryu] does not join the singing” (Taittirīya-saṃhitā 6.3.1) becomes the supplement of the non-specific text of a different branch, viz. “The sacrificial priests join the singing”—so in the matter under discussion too, viz. abandoning, there is the insertion of taking.

(The author) shows that this view that general texts imply specific texts is supported by another teacher as well, thus: “It has been said”, i.e. said by Jaimini, viz. “Let it be, on the contrary, supplementary to the text, on account of the impropriety of an option. Let the injunction refer to the same place” (Pūrva-mīmāṃsā-sūtra 10.8.15). The establishing of the double implication (viz. of abandoning and taking) in places concerned, on the other hand, should be known to be meant for the benefit of the respective readers of those (treatises). Hence it is established that “in the abandonment”, taking is inserted.

Here ends the section entitled “Abandonment” (11).

Comparative views of Baladeva:

This is sūtra 27 in his commentary. He begins a new adhikaraṇa here (two sūtras), concerned with an entirely different question, viz, whether the meditation on the Lord is obligatory or optional to the freed souls. He reads “Āchanda” instead of “chanda”, interpreting it as ‘option’. Hence the sūtra: “But on the destruction (of bondage, the released souls are under no obligation to practise meditation, because they have obtained) nearness (i.e. upāyana) (to the Lord), (and) because scriptural texts are supplementary (to this, i.e. are meant for leading the soul to this stage, viz. release), just as the singing of hymns with the kuśa (in hand) is optional (i.e. āchanda) (for a student who has finished his daily duties), it is declared (by Scripture)”. That is, the aim of all scriptural texts is to teach men meditation so that they may attain salvation. When that end is reached, i.e, men are freed and approach the Lord, it is no longer necessary for them to go on with further meditation.[14]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Quoted by Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja, Bhāskara and Śrīkaṇṭha.

[2]:

Op. cit.

[3]:

Op. cit.

[4]:

P. 901. The text reads: “Samayābiṣite sūryye Niraṇyeṇa vahirbhyām ca”, etc.

[5]:

A hymn or a formula consisting of sixteen parts.

[6]:

Quoted by Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja, Bhāskara and Śrīkaṇṭha.

[7]:

One of the four classes of priests. His special duty was to measure the ground, build the altar, prepair sacrificial vessels, etc., and he had to recite the hymns of the Yajur-veda while doing these duties.

[8]:

Correct reading; Na upagāyet=should not sing.

[9]:

P. 175, line 9, vol. 2. Quoted by Rāmānuja, Bhāskara and Quoted by Śrīkaṇṭha.

[10]:

Quoted by Rāmānuja, Bhāskara and Śrīkaṇṭha.

[11]:

P. 031, vol. 2. Quoted by Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja, Bhāskara and Śrīkaṇṭha.

[12]:

Hence these two cases present no difficulty.

[13]:

I.e. in the text of the Kauṣītakins both abandoning and taking are mentioned, while in the texts of the Tāṇḍins and the followers of the Atharva-veda only abandoning is mentioned. Kow if it be said that taking is inserted from the first to the last two, then abandoning too may very well be so inserted. In that case, the mention of abandoning in the last two texts becomes meaningless.

[14]:

Govinda-bhāṣya 3.3.28, pp. 155-158, Chap. 3.