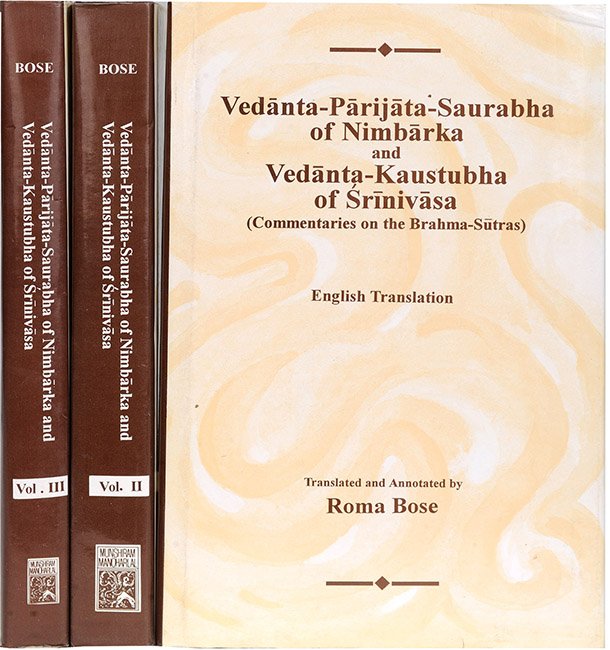

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 2.2.28, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 2.2.28

English of translation of Brahmasutra 2.2.28 by Roma Bose:

“(There is) no non-existence (of external objects), on account of perception.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

There is “no non-existence” of external objects as held by the maintainers of the reality of consciousness alone; but they are, indeed, existent. Why? “On account of perception.”

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Now, the view of the Yogācāra is being disposed of.

The Yogācāra Buddhist, the maintainer of the reality of consciousness alone, holds that those objects which are other than consciousness are all non-existent. Thus, to think that manifold external objects exist is an error. There are only manifold cognitions which are momentary, variegated, perceptible and have definite forms. Only cognitions like ‘blue’, ‘yellow’, which have definite forms, are revealed (directly to the mind). It must be admitted certainly even by the maintainers of the reality of external objects that the cognitions arising from the contact of sense-organs with those particular objects have forms of those objects respectively. If this he so, then all practical transactions being possible through those forms alone, what is the use of imagining external objects? It (viz. a cognition) being self-manifesting like a lamp, is directly perceived. If what is non-perceived be cognized, then there will he non-distinction between one’s own cognitions and the cognitions of others. But there is indeed a distinction (between them). A man acts or refrains from acting on the basis of his own cognitions. This has been declared by Viprabhikṣu as well thus: ‘There is no understanding of the meaning of what is non-perceived. The cognitive self, though non-divided, is yet looked upon by men of perverted understanding to be possessed of the differences of object perceived, the perceiver and consciousness’. Thus, the object-form is the object to be known, the perceiver-form is the act of knowledge, and his consciousness is the result, and thus these three are imagined in one and the same process of consciousness. Hence there are no external objects.

For this reason also (there are no external objects—viz.): On account of being uniformly perceived together, there is no difference between ‘blue’ and its cognition. Whenever there is the cognition of blue, blue, too, is cognized at the very same moment. Hence, there is no difference between these two.

For this reason, too, (there are no external objects, viz.): The cognitions in our waking state are devoid of (i.e. do not correspond to) external objects, because they are mere cognitions, like the dream-cognitions and the rest.

If it be asked: How can there be a variety of cognitions in the absence of external objects? We reply: owing to the variety of the past impressions. The variety (of cognitions) is explicable by reason of the fact that the cognitions and the past impressions stand in the relation of mutual causes and effects, like the seed and the shoot.

(Correct conclusion.) On this suggestion, we reply: The nonexistence of external objects is not possible. Why? “On account of perception,” i.e. because of the direct perception of external objects, other than cognitions. Although the individual soul, having the stated marks, is eternal knowledge by nature and its attribute of knowledge, too, is indeed eternal like the ray of the sun, yet since it has its knowledge veiled by nescience due to the beginningless māyā,[1] it errs in cognizing objects in birth after birth, as well as in one birth even. And it knows once more the sun and the rest, installed by the Highest Self, as well as the objects collected by its father and forefathers, which are all already existent, from the surrounding company of people. The sense is that, hence, there is no non-existence of the objects which are different from knowledge, the sun and the moon, fire, mountain, the earth, water, cow, horse and the rest being established on the ground of direct perception.

The argument,—viz. It is to be admitted certainly even by the maintainers of the reality of external objects that cognitions arising from the contact of sense-organs with those particular objects have the forms of those objects respectively. If this be so, then all practical transactions being possible through those forms alone, what is the use of imagining external objects?—is not tenable, since in the absence of objects, the cognitions of the objects cannot have forms similar to them. Thus, an external object is other than knowledge and its knowledge is other than it.

The argument—viz. that owing to their being uniformly perceived together, there is no difference between blue and its perception,—too, is not tenable, for there is an admission of difference through this very admission of a simultaneous perception.[2]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

I.e. prakṛti or matter.

[2]:

That is, to say that A and B are perceived together is to say that there is a difference between them, Otherwise there is no sense in saving that A and B are perceived together.