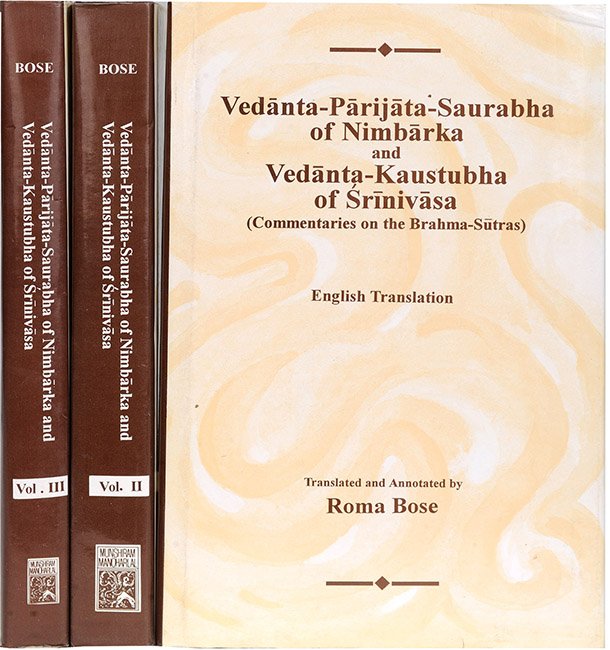

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 2.2.3, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 2.2.3

English of translation of Brahmasutra 2.2.3 by Roma Bose:

“And if it be argued that (pradhāna acts spontaneously) like milk and water, (we reply:) there too (lord is the inciter).”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

If it be argued that like milk, etc. pradhāna acts for the origin and the rest of the world by itself, (we reply:) that “there too” the Supreme Being is the inciter is learnt from the scriptural text: “Who abiding within water” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.7.4 [1]).

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

If it be argued: How can it be said that on account of the impossibility of spontaneous activity on its part the non-sentient pradhāna is not the cause of the world? Just as milk, though non-sentient, is by itself transformed into the form of sour milk, and flows spontaneously for the nourishment of the calf; and just as water discharged from the cloud is transformed into the form of various saps of the earth, as well as into the forms of ice, bubble and the rest, and pours down spontaneously for the growth of plants and the rest, as well as flows on, so exactly pradhāna too, independent of a sentient being, having entered into a state of mutual inequality of the guṇas, is transformed into many forms,—

We reply: “There too”. That is, in the case of milk and the rest too, no activity is possible independently of a sentient being. On the contrary, milk and the rest attain the form of sour milk and so on only when superintended by a sentient being. It is the cow herself, fond of her calf, that makes the milk flow out of filial affection, and being liquid the milk oozes out. If it be argued that even when the calf is dead, the presence of the milk is observed, and hence to say that it is the cow that makes the milk flow out of filial affection does not stand to reason,—(we reply:) there is the flow of the milk then by reason of her remembrance of the caff, or else it is explicable on the ground of her love for her master. [2]

Water, too, comes to have the form of ice, bubble and the rest only when superintended by a conscious being; appears to be of the form of various saps through its contact with the earth; and flows on as dependent on a low ground [3] and on account of being liquid. Everything being superintended by a sentient being, the above examples all fit in, in accordance with the scriptural texts: ‘Who abiding within water’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.7.4), ‘“At the command of this Imperishable, Gārgi, some rivers flow to the east”’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.8.9) and so on. Hence the inference (i.e. the inferrible pradhāna) is not the cause of the world.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Quoted by Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja and Bhāskara.

[2]:

I.e. the cow gives milk even when the calf is dead because she still remembers the calf, or because she loves her master and wants to be of benefit to him.

[3]:

I.e. the flowing of the water depends on its being on a sloping ground.