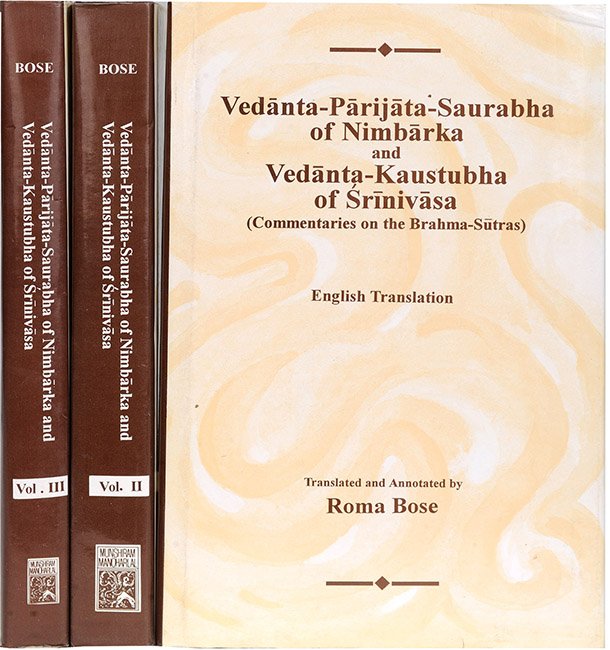

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 2.2.1, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 2.2.1

English of translation of Brahmasutra 2.2.1 by Roma Bose:

“And on account of the impossibility of arrangement also, not the inference.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

Pradhāna, knowable through inference[1] is not the cause of the world. Why? “On account also of the impossibility” of a varied “arrangement” from it, not acquainted with the arrangement of the objects to be created.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Thus, with a view to inducing those who desire for salvation to the hearing, thinking and the like of the nature, attributes and the rest of the Supreme Person, it has been firmly established above by the reverend author of the aphorisms that Lord Vāsudeva, the Highest Person, omnipotent, the Lord of all, and the Supreme Person, is the cause of the origin and the rest of the world; and that the views of the opponents arise not supported by Scripture has been shown under the aphorism: “Because (the creator of the world) sees, (pradhāna is) not (the creator), (it is) non-scriptural” (Brahma-sūtra 1.1.5). Now, with a view to establishing the acceptability of the conclusion of the Vedāntins, the reverend author of the aphorisms is exposing, in this section, the fallaciousness of the arguments put forward by the opponents. It is not to be said that those who desire for release being benefitted through a mere exposition of the conclusion of the Vedāntins, what is the use of villifying the views of the opponents? Since just as when a man, giving up the most beneficial food, is about to take injurious poison and the like, people try to induce him to food and to dissuade him from poison, etc. by pointing out the unwholesomeness of the latter, so the villification of the view of the opponents is justifiable for the purpose of preventing people from accepting the views which are opposed to the Veda, and for inducing those desiring for emancipation to our own view.

Now, the Sāṃkhyas, discarding the Highest Person, omnipotent and omniscient, as the cause of the origin and the rest of the world, hold prakṛti, devoid of any connection with Him, non-sentient and the equilibrium of the three guṇas, to be the cause of the world. This has been said in the treatise treating of the sixty (categories)[2]: “The primary prakṛti (i.e. matter) is not an effect. There are seven, beginning with mahat, which are (both) causes and effects. There are sixteen which are effects (only). ‘Puruṣa (i.e. soul) is neither a cause, nor an effect’ (Sāṃkhya-kārikā 3[3]). They state the five reasons for the existence of prakṛti thus: The cause is pradhāna, ‘(1) on account of the transformation of the divisions[4]; (2) on account of concordance[5]; (3) on account of the activity preceding from power[6]; (4) on account of the distinction between the cause and the effect[7]; (5) on account of the non-distinction of what is possessed of all form’ (Sāṃkhya-kārikā 15[8]). The word ‘Vaiśva-rūpa’ means the same as ‘Viśva-rūpa’ or what is possessed of all forms, i.e. the universe of varied configurations. Whatever is limited is due to a common cause, like pots and the rest. Similarly, a mahat and ahaṃkāra, the five pure essences, the eleven sense-organs, and the five great elements which are limited are ‘divisions’; they are due to one cause which is unlimited in space and time and the common substratum of three guṇas.[9] Whatever is observed to be connected with something else, is due to that one cause; as dishes and the rest, connected with the clay, are due to it. Similarly, the external and internal divisions, connected with pleasures (sattva), pain (rajas) and delusion (tamas) should properly be due to a common cause consisting in pleasure, pain and delusion.[10] Similarly, just as there is the origin of pots and the like from the power of the cause, so the origin of the effects like mahat and the rest, too, must be held to be due to the power of the cause. This being so, the cause, possessed of such a power, is pradhāna.[11] Moreover, it is observed that there is a distinction betweeen the effects, like ear-rings and the rest, and the cause, similar to them, such as gold and the rest, as well as a nondistinction. Similarly, there is both distinction and non-distinction on the part of the manifold universe. Through these two, a cause, viz. the unmanifest which is the substratum of all beings and consists of the three guṇas in a state of equilibrium, is inferred.[12]

On this suggestion, the author replies: “The inference”, i.e. what is inferred, viz. pradhāna, not having Brahman as its common cause, is not the cause of the world. Why? “On account of the impossibility of arrangement,” i.e. because it is impossible that the arrangement of the world,—variegated by the aggregate of manifold objects of enjoyment, conforming to the diverse works of the souls,—can arise from pradhāna, not having Brahman for its cause, an object of inference, non-sentient and devoid of any knowledge of the objects to be created; as we see in ordinary life that the arrangement of manifold and variegated palaces, chariots, ornaments and the rest is due to one who is possessed of the knowledge of the objects to be created.

The particle “and” (in the sūtra) indicates that the reasons, intended for proving the existence of pradhāna, can very well be set aside by valid opposite arguments, since the following inference establishes the non-validity of the object established (by the Sāṃkhya, viz. pradhāna):—

Pradhāna as admitted by the Sāṃkhyas and not having Brahman for its soul, is non-existent; because it is not perceived.

Whatever is this (i.e. not perceived) is that (i.e. non-existent); like the sky-flower.

Whatever is not this (i.e. not non-perceived) is not that (i.e. not non-existent); like the sun.

Comparative views of Rāmānuja and Śrīkaṇṭha:

They take this and the next sūtra as one sūtra.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See footnote 1, p. 42 of the book.

[2]:

Peculiar to the Sāṃkhyas.

[3]:

p. 4.

[4]:

I.e. on account of the limitedness (pariṇāma) of the effects (bheda) like mahat and the rest. Thus: Whatever is limited has a cause, like the pot.

The effects are limited.

* they have a cause, viz . pradhāna.

I.e. all the effects possess the common qualities of pleasure (sattva), pain (rajas) and delusion (tamas). Hence they must have a common cause which possesses all these qualities, viz. pradhāna.

[5]:

I.e. the cause can give rise to the effect only if it has the requisite power. Now pradhāna alone has the power to give rise to mahat and the rest.

[6]:

The difference of the effect from the cause proves the existence of the cause. Thus, the difference of the pot from a lump of clay, viz. the first can fetch water, the second not—proves that the pot has clay for its common cause. Similarly, from the mahat and the rest we argue to pradhāna, different from them.

the rest.

[7]:

I.e. the whole universe merges in a common cause during dissolution, and such a cause is pradhāna. Vide Candrikā-vyākhyā of Sāṃkhya-kārikā, pp. 18-19; also Gauḍapāda-bhāṣya on same, pp. 13-14.

[8]:

P. 18.

[9]:

This explains the first reason.

[10]:

This explains the second reason.

[11]:

This explains the third reason.

[12]:

This explains the fourth and the fifth reasons.