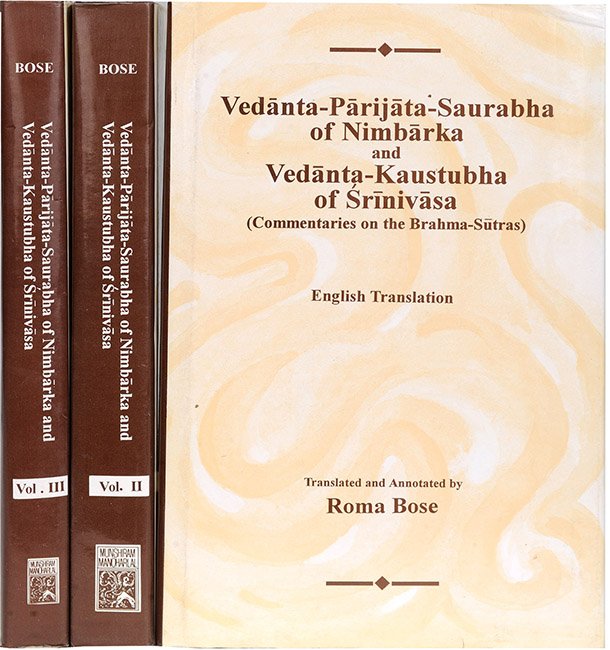

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 2.1.14, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 2.1.14

English of translation of Brahmasutra 2.1.14 by Roma Bose:

“(There is) non-difference (of the effect) from that (viz. the cause), on account of (the texts) beginning with the word ‘beginning’ and the rest.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

There is “non-difference” between the effect and the cause, and not absolute difference. Why? On account of the texts: ‘“The effect having its beginning in speech, is a name, the reality is just the clay”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.1.4[1]), ‘“All this has that for its soul. That is true... Thou art that”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.8.7, 6.9.4, 6.10.3-6.16.3[2]), “All this, verily, is Brahman” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1[3]).

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

In the first chapter, Brahman has been described many times as different from the sentient and the non-sentient, in order that there may be a proper discrimination between the peculiar natures of these three realities respectively.[4] Here, on the other hand, the nondifference of the world, the effect, from Brahman, the cause, resulting from the absence of separate existence, activity and the rest (on the part of the former), has been established under the aphorism: “If it be objected that (in that case the effect must be) non-existent, (we reply:) no, on account of there being a negation merely” (Brahma-sūtra 2.1,7) and so on. Now, with a view to confirming the stated conclusion, the author is refuting the view of the Vaiśesikas who hold that the effect is not non-different from the cause, but is something which originates (i.e. is an absolutely new creation).[5]

The compound (“tad ananyatvam”) is to be explained as follows: There is non-difference between the two, viz. the cause and the effect; or, there is non-difference of that, viz. the world, the effect, from Brahman, the cause; or, there is non-difference of the effect from that, viz. the cause. That is, the effect, which is of the form of the sentient and the non-sentient, which is limited, has many names and forms, and is dependent, is non-different from Brahman, the Supreme Cause, possessing the sentient and the non-sentient as His powers, unlimited, denoted by words like ‘one’, ‘without a second’ and so on, capable of abiding voluntarily in the causal state and in the effected state, and prior to the entire universe. The author states the proof with regard to it in the words: “on account of (the texts) beginning with the word ‘beginning’ and the rest”. (The compound “ārambhana-śabdādibhyaḥ” is to be explained thus:) The texts of which the beginning is the word ‘beginning’, on account of them. That is, on account of the texts: ‘“The effect, having its beginning in speech, is a name, the reality is just the clay’” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.1.4), “‘The existent alone, my dear, was this in the beginning, one, without a second”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.2.1), “‘He thought, ‘May I be many’, may I procreate”. He created the light’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.2.3), ‘“All that has this for its soul. That is true. That is the soul. Thou art that”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.8.7, etc.), “All this, verily, is Brahman, emanating from Him, disappearing into Him and breathing in Him” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1), “That was unmanifest then. It became manifest by name and form” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 1.4.7) and so on. There are many texts of such kinds which establish the non-difference of the world, the effect, from Brahman, the cause, but which are not quoted here for avoiding prolixity.

Among these, the meaning of the text beginning with the word ‘beginning’ (ārambhaṇa) is as follows:

The Chandogas, having made an initial statement to the effect that through the knowledge of the material cause there arises the knowledge of all the effects, in the passage: ‘“Whereby the unheard becomes heard, the unthought thought, the unknown known”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.1.3), state a parallel instance to establish it, in the passage:

‘“Just as, my dear, through one lump of clay, everything made of clay may be known,—the effect, having its beginning in speech is a name, the reality is just the clay”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.1.4[6]). That is, just as ‘through, one lump of clay’ being known as clay, ‘everything made of clay’, i.e. the group of the evolutes of clay, may be known, since they are all made of clay;—for such a group of evolutes ‘has its beginning in speech’, i.e. is designated by speech. Speech is of two kinds: ‘effect’, i.e. meaning, and ‘name’, i.e. word. The function of speech rests on these two, viz. meaning and word, e.g. we say: ‘Fetch water by the pot’. Hence, ‘the truth’ is that the evolute, characterized by having a broad bottom and resembling the shape of a belly, having the name ‘pot’, and conducive to the function of fetching water and so on, is ‘just clay’. That is, the view that the effect is different from the cause, on account of the difference of individuality and conception, is incorrect, for it is not possible to attribute the individuality or the conception of a pot to the wind and the rest which are different from clay.[7] If the effect is to originate from the non-existent simply, then that would lead to the origin of everything everywhere, as well as to the futility of the activity of the agent. So desist from further arguments.

Comparative views of Śaṅkara:

Each commentator develops his peculiar theory in this connection. Śaṅkara understands the word “Aṇanyatva” as absolute identity, interprets the word ‘vācārambhaṇa’ to mean ‘that which begins from speech only, but does not exist in reality’, and thereby develops his theory of Vivarta at great length.[8]

Comparative views of Rāmānuja:

He understands the word “ananyatva” as non-difference, like Nimbārka, but connects it with his peculiar doctrine of the soul-body relation between Brahman and the universe.[9] He interprets the phrase: “vācārambhaṇa” as follows: ‘vācā’ means: on account of speech, i.e. on account of activity preceded by speech; ‘rambhaṇa’ means: what is touched. Hence the text means: On account of speech, (i.e. for the sake of certain activities, like the fetching of water and the rest,) there is touched (by the clay) an effect and a name; i.e. clay is transformed into a particular effect having a special name, in order that a certain activity may be accomplished.[10]

Comparative views of Bhāskara:

He, too, understands the word “ananyatva” as non-difference. He criticizes the Śaṃkarite view at length and insists on the reality of difference,[11] and interprets the phrase “vācārambhaṇa” like Śrīnivāsa.

Comparative views of Śrīkaṇṭha:

He, too, understands the word “ananyatva” as non-difference,[12] He explains the phrase “vācārambhaṇa” in the next sūtra, and gives two alternative explanations, viz. “That which is the beginning, i.e. the cause, of speech, i.e. of speech and practical activity”.[13] Hence, the text means that an effect (vikāra) is a name (nāma-dheya) which is the cause of speech and practical activity, i.e. of such expressions ‘Fetch water in a pot’ and so on. The second explanation is: “That which has speech for its beginning”.[14] Hence the text means that an effect (vikāra) is simply the object of such expressions: ‘This is a pot’, i.e. a special condition the clay has assumed for practical purposes, but is not a separate substance from the clay.

Footnotes and references:

[2]:

Quoted by Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja, Bhāskara, Śrīkaṇṭha and Baladeva.

[3]:

Quoted by Rāmānuja.

[4]:

[6]:

The passage is: “Yathā saumya! ekena mṛt-piṇḍena sarvaṃ mṛnmayaṃ vijñātaṃ syāt, vācārambhaṇaṃ vikāro nāmadheyaṃ mṛttikety eva satyam”.

[7]:

If the effect were absolutely different from its cause, then any and everything, e.g. wind, might very well have been conceived to be a pot. But this is never the ease, since clay alone, and nothing else, is conceived to be so.

[8]:

“Vācaiva kevalam asti....na tu vastu-vṛtteṇa vikāraḥ kaścid asti”, etc. Brahma-sūtras (Śaṅkara’s commentary) 2.1.14, p. 464.

[10]:

“Ārabhyate ālabhyate spṛśate,” etc. Śrī-bhāṣya (Madras edition) 2.1.15, p. 40, Part 2.

[12]:

Brahma-sūtras (Śrīkaṇṭha’s commentary) 2.1.15, p. 22, Parts 7 and 8.

[13]: