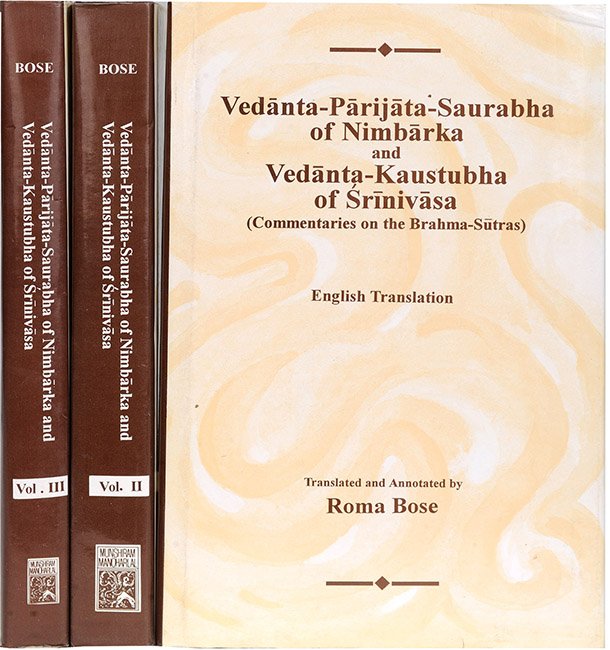

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 1.4.10, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 1.4.10

English of translation of Brahmasutra 1.4.10 by Roma Bose:

“And on account of the teaching of the fashioning (of the universe), there is no contradiction, as in the case of the honey (-meditation).”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

No contradiction is involved in taking one and the same substratum of qualities as unborn and having, at the same time, Brahman for its material cause. On account of the teaching of the creation of the universe from Brahman, the cause of the world and possessing subtle powers, both fit in, “as in the case of the honey-meditation”.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

To the objection, viz. How can an unborn one be something generated, the author replies:

The word “and” is for disposing of the objection. There is no contradiction in taking an unborn one as something generated. Why? “On account of the teaching of fashioning.” The word “fashioning” means making or creation, on account of the teaching of that[1], i.e. on account of the teaching of the creation of the universe from Brahman, possessing subtle powers, in the passage: ‘From this, the Māyin creates this universe’ (Śvetāśvatara-upaniṣad 4.9). The unmanifest prakṛti, subtle in form and a power of Brahman, is said to be unborn because of being non-different from Brahman as His power. That very same prakṛti, emanated from the possessor of powers or Brahman and abiding in the form of effects, is said to have Brahman for its beginning or cause, and hence there is no contradiction. Here the author states a parallel ease in the words: “As in the case of the honey-meditation”. In the honey-meditation,[2] which begins: ‘Verily, this sun is the honey of the gods’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.1.1), in the concluding text: ‘Then, having risen up from thence, it will neither rise nor set, it will remain alone in the middle’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.11.1), the very same thing, which in. its causal state abides in a subtle form and is not, as such, designable as honey, is, in its effected state, imagined to be the honey, enjoyable by gods like Vasu and the rest, and to he possessed of rising and setting, without giving rise to any contradiction. Similarly, the very same eternally existent prakṛti is designated by the sacred text in its causal form in relation to the bondage and release of the eternally existent individual soul. Here, the individual soul, indicated by the term: ‘unborn one’ (aja),—eternal by nature, carried away by the current of beginningless karmas, and hence devoid of a true knowledge of the real nature of itself or of the Supreme Being,—having identified itself through nescience with the bodies, such as of men, gods and the rest which are the evolutes of prakṛti, lies by, enjoying sounds and the rest, the parts of prakṛti; such a one, devoid of the bliss of Brahman, is said to be ‘bound’. But one, who having attained by chance the grace of the Lord through humbleness and the like, and having attained the bliss of Brahman by means of the repetition of the means,—‘hearing’ (śravaṇa) and the rest of the Vedānta,—learnt from a holy spiritual preceptor, discards prakṛti, is said to be ‘freed’. If in accordance with the etymology: ‘An unborn one (ajā) is one that is not born’, it is said that the unborn one is not prakṛti, eternally existent and having Brahman for its soul, then the conventional distinction between the bondage and release of the created souls cannot be explained by the non-sentient pradhāna, devoid of any connection with Brahman. Hence it is established that the unborn one, mentioned in the sacred text, has Brahman for its soul.

Here ends the section entitled ‘The cup’ (2).

Comparative views of Śaṅkara and Bhāskara:

Interpretation different: viz. ‘On account of the teaching of an imagination (i.e. a metaphor); there is no contradiction’. That is, the word ‘ajā’ here does not stand for one who is literally unborn, but simply metaphorically represents prakṛti, the source of all things, as a she-goat, just as the sun, though not really honey, is metaphorically represented as such in the Chāndogya.[3]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

This explains the compound: ‘kalpanopadeśāt’.

[2]:

Vide Vedānta-kaustubha 1.3.31-33. See footnote 1, p. 193.

[3]:

Ś.B. 1.1.10, pp. 404-5. Brahma-sūtras (Bhāskara’s Commentary) 1.1.10, p. 758. Cf. Rāmānuja’s criticism of this interpretation.