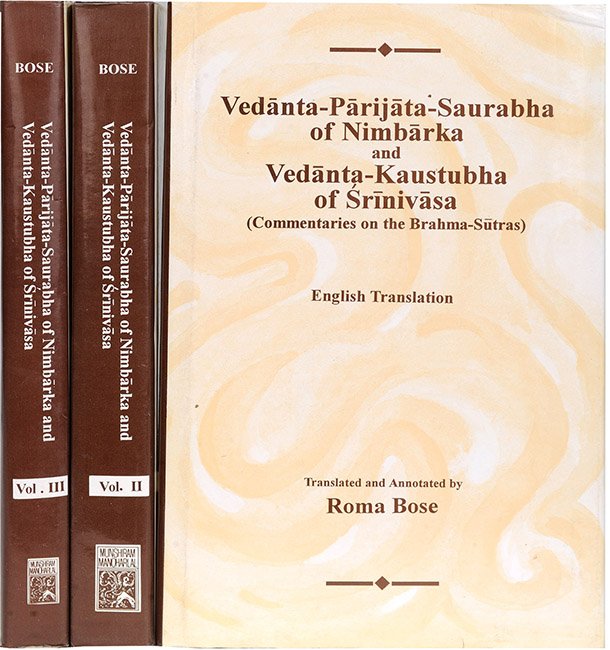

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 1.3.26, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 1.3.26

English of translation of Brahmasutra 1.3.26 by Roma Bose:

“Even those who are above them (i.e. men) (are entitled to the worship of Brahman), (so) Bādarāyaṇa (holds), because of possibility.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

The gods and the rest also, who are above men, are entitled to such a worship of Brahman,—so thinks the reverend “Bādarāyaṇa.”

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

It has been said in the last section that the text about the Person of the size of merely a thumb is explicable in reference to the heart of men, as men are entitled to Scripture. Now, incidentally, the question as to whether or not gods too are entitled to the worship of Brahman is being considered.

In the Bṛhadāraṇyaka, we read: ‘Whoever among the gods was awakened to this, he alone became that; likewise among the sages’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 1.4.10). (The sense is:) Whoever among the gods, and similarly among the sages ‘was awakened’, i.e. directly perceived Brahman, ‘he alone’ attained the nature of Brahman. Here, on the doubt, viz. whether or not the gods are entitled to the worship of Brahman, which is a means to attaining His nature, if the suggestion be: As men are entitled to Scripture; and as Indra and the rest are incapable of practising meditation,—seeing that they, whose bodies consist of sacred texts, are not possessed of physical bodies, [1]—the worship of Brahman is not possible on the part of the gods,—we reply: Such a worship of Brahman is possible on the part of gods as well, who are “above” men,—so the reverend “Bādarāyaṇa” thinks. Why? “On account of possibility,” i.e. because the worship and the like of Brahman, leading to salvation which is characterized by the attainment of Brahman and is preceded by the cessation of all retributive experience due to their own works, is possible on their part as well. Thus, although they have supermundane and celestial enjoyment, yet since such an enjoyment is subject to the faults of non-permanency, surpassability and the rest, its cessation, one day or other, is possible; hence, a desire for salvation, too, is possible on their part, by reason of their learning the unsurpassability, supreme blissfulness and permanency of the attainment of the nature of Brahman; and finally through this desire for salvation, a worship of Brahman, too, is possible on their part[2] there being proofs establishing their right to the worship of Brahman, viz. the texts: ‘For one hundred and one years, forsooth Indra dwelt with Prajāpati, practising chastity’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 8.11.3), ‘Verily, Bhṛgu, the son of Varuṇa, approached his father Varuṇa, (with the request) “Sir, teach me Brahman”’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 3.1.1) and so on. Similarly, corporality, too, is possible on their part in accordance with text about the evolution of name and form,[3] as well as in accordance with sacred formulae, explanatory and glorificatory passages and tradition.[4] Thus it is declared by Scripture: ‘When about to say “vaṣat”, he should meditate on that deity for whom the offering is taken’ (Aitareya-upaniṣad Br. 11.8[5]). Here, no meaning of the text being possible unless the god referred to, be possessed of a body,[6] the god must be understood to have a body. In tradition too, the sun, the moon, Vasu and the rest are well-known to have bodies. The sons of Kuntī were born from gods like Dharma and the rest, possessed of bodies.[7] In the Purāṇas, too, there is a multitude of legends of various kinds about them, possessing bodies. The verses from those chapters are not quoted here for fear of increasing the bulk of the book.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

That is, in order that one might carry on meditation, one must have a physical body, which a god lacks. Hence a god cannot practise meditation.

[2]:

That is, just as in the case of a man, the non-permanency of the earthly enjoyment leads him to seek for salvation, which yields a permanent fruit, and that, again, leads him to worship the Lord as a means thereto, so exactly the non-permanency of the heavenly enjoyment leads a god to seek for salvation, which leads him to worship the Lord.

[3]:

Vide Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.3.2-4.

[4]:

Mantras, artha-vāda and itihāsa.

[6]:

[7]:

Kuntī, the wife of Pāṇḍu, had, with his approval, three sons, Yudhiṣṭhira, Bhīma and Arjuna, by the three deities, Dharma, Vāyu and Indra respectively. Vide Mahābhārata (Asiatic Society edition) 1.4760 et seq. (chap. 123), pp, 174 et seq., vol. 1.