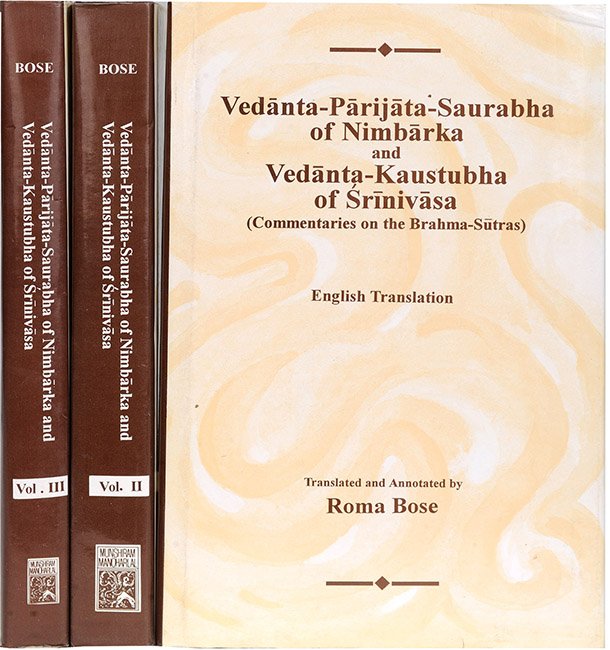

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 1.2.22, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 1.2.22

English of translation of Brahmasutra 1.2.22 by Roma Bose:

“That which possesses the qualities of invisibility and so on (is brahman), on account of the mention of (his) qualities.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

That which is mentioned by the Ātharvaṇikas in the text: ‘Invisible’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.6[1]) and so on, as ‘possessed of the qualities of invisibility and the rest’, is the Highest Self alone. Why? “On account of the mention” of His “qualities” in the passage ‘He who is omniscient’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.9[2]), etc.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

In the preceding section, pradhāna was set aside on the ground of qualities like ‘being a seer’ and the like which belong to a sentient being only. Now, by showing that the text: ‘Now, the higher is that whereby that Imperishable’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.5), and so on refers to Brahman, the author is disposing of the objection, viz. Let pradhāna be understood here (in the above text), owing to the absence of that (i.e. owing to the fact that the above text contains no reference to the qualities of a sentient being).

In the Ātharvaṇa, it is said: ‘There are two knowledges to be known’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.4). Among these, the knowledge of works, viz, the Ṛg-veda and the rest, is the lower.[3] With a view to teaching the higher, viz. the knowledge of Brahman, in contrast to it, it is said: ‘Now, the higher is that whereby the Imperishable is apprehended, that which is invisible, incapable of being grasped, without family, without caste, without eye, without ear, it is without hands and feet, eternal, all-pervasive, omnipresent, excessively subtle, it is unchangeable, which the wise perceive as the source of beings’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.5-6), ‘Without the vital-breath, without mind, pure, higher than the high Imperishable’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 2.1.12) and so on. Here a doubt arises as to whether here the Imperishable, the source of beings and possessed of the qualities of invisibility and the rest, is pradhāna, or the individual soul, or the Highest Self. The prima facie view is as follows:—As invisibility and such other qualities are possible on the part of pradhāna and the individual soul; as pradhāna is established to be the source of beings; and as the individual soul too, the cause of the body and the rest through its own works, can be so,—let one of these two be the Imperishable.

With regard to this, we reply: The Imperishable, the source of beings and possessed of the qualities of invisibility and the rest, is the Highest Self alone. Why? “On account of the mention of qualities”, i.e. because in the passage: ‘He who is all-knowing, omniscient, whose penance consists of knowledge, from Him alone Brahman, name and form, and food arise’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.9), the permanent attributes of the Highest Self, viz. omniscience, etc. are stated, with a view to laying down the attributes of the Imperishable, the source of beings.

If it be objected: This view is not reasonable. Having referred to the Imperishable in the passage: ‘The Imperishable is apprehended’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.5), then again having designated the Imperishable as a limit in the passage: ‘Higher than the high Imperishable’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 2.1.2), the text next goes on to designate the meaning of the word ‘higher’ as the Highest Self, in the passage: ‘He who is all-knowing’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.9). If here the Highest Self be understood by the word ‘Imperishable’ in the first passage, then how can the text: ‘Higher than the Imperishable, the Light’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 2.1.2) be possible, it being impossible for one to be higher than one’s own self, and there being no reality higher than Brahman, the Imperishable, the cause of the world and the topic of discussion, as evident from the declaration by the Lord Himself, viz. ‘“There is nothing else, higher than me, O Dhanañjaya”!’ (Gītā 7.7), as well as from the scriptural text: ‘There is nothing higher than the Person’ (Kaṭha 3.11)? Hence, let either pradhāna or the individual soul be the meaning of the word ‘Imperishable’, mentioned first, (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.5); and let the Highest Self, higher than that high Imperishable, be omniscient,—

(We reply:) Not so, because the word ‘Imperishable’, mentioned for the second time, (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 2.1.5) does not refer to the Highest Self. Thus, from the knowledge, called ‘higher’,—mentioned in the passage: ‘The higher is that whereby that Imperishable is apprehended’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.5),—it is gathered that the Imperishable is the Highest Brahman alone, since no other knowledge, except that of Brahman, can be high. Thus, having begun with the Highest Self, denoted by the word ‘Imperishable’ and celebrated in the texts: ‘He teaches in truth that knowledge of Brahman whereby one knows the Imperishable, the Person, the True’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.2.13), ‘As the hairs and the body-hairs arise from a living person, so from the Imperishable arises this Universe’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.7), ‘As from a well-lit fire thousands of sparks of a similar form emit forth, so do, my dear, manifold existences from the Imperishable’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 2.1.1) and so on, and with the Imperishable, possessed of the attributes of invisibility and the rest, in the passage: ‘Now, the higher is that whereby that Imperishable is known’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.5), Scripture, with a view to demonstrating His qualities and nature, designates Him once more as ‘higher’ than the ‘Imperishable’, i.e. than the individual soul which is His own part; as well as than the ‘high’, i.e. pradhāna which His own power,—i.e. designates Him as their source and controller. Or, else, the ‘Imperishable’ is that which pervades the mass of its own modifications; ‘higher’ than that imperishable is pradhāna which is superior to its own modifications; and ‘higher’ than this pradhāna is the Highest Self. Or, else, the Supreme Person is ‘higher’ than the Person within the aggregate (or Hiraṇyagarbha) who is higher than the Imperishable, viz. pradhāna,—this is the sense.

Footnotes and references:

[2]:

Op. cit.

[3]:

Vide Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.5.