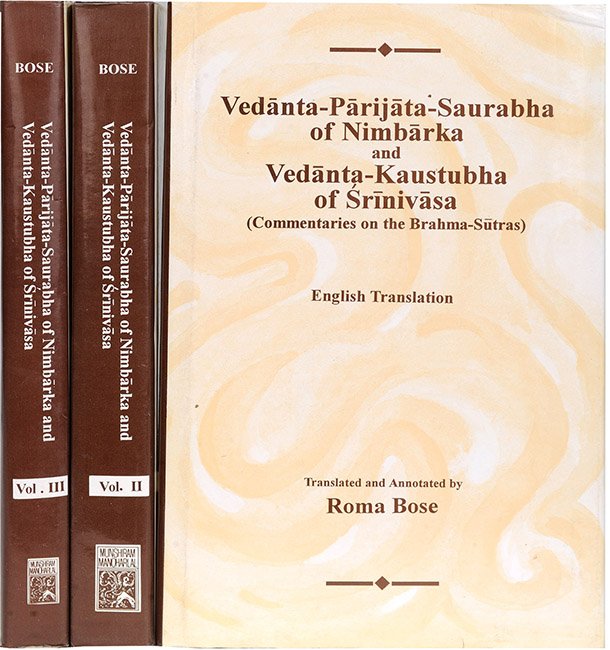

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 1.1.4, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 1.1.4

English of translation of Brahmasutra 1.1.4 by Roma Bose:

“But that (viz. that Brahman has Scripture as His sole proof) follows from the concordance (of all scriptural texts with regard to Brahman).”

Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha

If an objection be raised, viz.: In as much as the entire Veda is concerned with action (i.e. injunctions and prohibitions), the Vedānta-texts too, which are concerned with a different topic, are solely concerned with injunctions by way of establishing the excellence of the agent, who is a part of sacrifices,—just as the artha-vāda texts[1] are indirectly unanimous with the injunctive-texts, by way of establishing their excellence. Hence, how can Brahman have Scripture as His sole proof?[2]—the correct conclusion is as follows:

‘That’, i.e. Brahman alone, the object of enquiry and the cause of the universe, has Scripture for His proof, and not action and the rest, since the entire Veda is in concordance in proving Him alone. (The word) “samanvayāt” is to be explained thus: “Samanvaya”. means concordance in respect of the primary import,—on account of that—“samanvayāt”. Or else, because there is concordance among the Vedas in point of proving Him alone,—so much in brief.

It cannot be said that such a concordance exists with regard to actions, since actions fulfil their purpose by simply giving rise to a desire for knowledge.[3] To say that Brahman is a subsidiary factor of sacrifices is a mere childish prattle, since He is an independent Being as the regulator of all -works, their agents and so on, and their instruments; and is the giver of fruits. On the contrary, works themselves are in concordance (with regard to Brahman) as assisting indirectly the rise of knowledge—which is a means to attaining Him,—by way of generating a desire for knowledge.[4] This is ascertained from the text concerning the desire for knowledge.[5]

If it he objected: It being established in Scripture that Brahman is not an object of the proof, viz. Word, just as He is not an object of the proofs, viz. perception and the rest,—Brahman has not Scripture as His sole proof,—we reply: Brahman, the object of enquiry, has Scripture alone as His proof and not anything else, on account of the concordance of all the scriptural texts, directly or indirectly, with regard to Him alone. Among these, there is a direct concordance among the texts concerning His characteristic marks, proof and the rest, since they are (directly) concerned with Him; and there is an indirect concordance among the texts concerning the Śāṇḍilya-vidyā,[6] the Pañcāgni-vidyā,[7] the Madhu-vidyā[8] and so on, as well as among those which are symbolic in nature.[9] Or rather, there is a direct concordance alone among all the texts whatsoever, though leading to different procedures,[10] since the topics of all these different texts being equally Brahman in essence, they are all to be understood in their primary and literal sense.[11] It is not to be feared that in that case, the texts which are concerned with the denial of the object (viz. Brahman) will be precluded,[12] since they too, as being concerned with denying any limit with regard to Brahman’s nature, attributes and the rest, refer to the very same topic (viz. Brahman).[13]

Moreover, we ask your Worship: Do you or do you not mean that Brahman is the object of the statement: ‘Brahman is not an object of knowledge’? If the first, then Brahman is proved to be describable and hence the proposition that He is not describable is set aside. If the second, then Brahman is describable all the more. Hence, the object of enquiry is Lord Vāsudeva alone, omniscient, possessed of all inconceivable powers, the cause of the origin and the rest of the universe, known through the evidence of the Veda alone, different and non-different from all and the soul of all. All Scriptures are in concordance with regard to Him alone—this is the settled conclusion of the followers of the Upaniṣads (viz. the Vedāntins).

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Thus, it has been said that Lord Kṛṣṇa, the substratum of great qualities and powers and the non-distinct material and efficient cause of the world, has the Veda alone for His proof. Now, with a view to confirming it, the author, by showing the concordance of the entire Veda with regard to that very Brahman, refutes the following objection, viz.; The entire Veda has been associated with action by Jaimini who holds: ‘Since Scripture is concerned with action, there is purport-lessness of what does not refer to it (viz. action)’ (Pūrva-mīmāṃsā-sūtra 1.2.1[14]). Hence, what is not concerned with action being laid down as purportless, the Vedānta-texts, too, all refer to action (otherwise they will all become purportless). Consequently, how can Brahman have the Veda as His sole proof?

The term “but” disposes of the (above) prima facie view. “That”, i.e. Brahman alone, the object of enquiry and the cause of the world, has Scripture for His sole proof. Why? “On account of concordance”, i.e. because there is concordance among all the Vedas with regard to Him alone. (The word “samanvayāt” is to be explained as follows:) “Samanvaya” means: ‘Concordance in point of entirety of statement’,—on account of that,—“samanvayāt”, i.e. the entire Veda is in concordance with regard to denoting Brahman entirely or Lord Kṛṣṇa, the object to be enquired into by one who desires salvation, the one identical material and efficient cause of the world, having Scripture as His source (i.e. proof), the controller of matter, soul, time and works, having His footstool honoured by the crowns (i.e. the bowed heads) of Brahmā, Rudra, Indra and the rest, having His greatness untouched by any odour of fault, the abode of infinite qualities like omniscience and the rest and to be approached by the freed. The following groups of texts are in concordance with regard to Him alone:—‘From whom verily all these beings arise’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 3.1), ‘From bliss alone, verily, do these beings arise’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 3.6), ‘From Him arise the vital-breath, the mind, and all the sense-organs’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 2.1.3), ‘“The existent alone, my child, was this in the beginning, One only, without a second” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.2.1). “He thought: May I be many, may I procreate”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.2.3), ‘From Nārāyaṇa arises the vital-breath,...from Nārāyaṇa arises Brahmā, from Nārāyaṇa arises Rudra’ (Nārāyaṇa-upaniṣad 1), ‘There was verily, Nārāyaṇa alone, neither Brahmā nor Īśāna (Mahā-upaniṣad 1.2), ‘Brahman, verily, was this in the beginning, one only’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 1.4.10.11). ‘Brahman, verily, was this in the beginning; he knew that self alone thus: “I am Brahman”’, ‘From Him arose all this’, ‘The self, verily, was this in the beginning, one only’ (Aitareya-upaniṣad 1.1.1), ‘From this self, verily, the ether originated’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.1), ‘The word which all the Vedas record’ (Kaṭha 2.15), ‘That, in regard to which all the Vedas are unanimous’ (Taittirīya-āraṇyaka 3.11.1[15]), ‘Entered within, the ruler of man’ (Taittirīya-āraṇyaka 3.11.1.2[16]), ‘To whom all the gods bow down’, ‘Brahman is truth, knowledge and infinite’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.1), ‘Knowing the bliss of Brahman’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.9), ‘Brahman is knowledge and bliss’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.9.28), ‘All this, verily, is Brahman’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1), ‘The self that is free from sins, without decay, without death, without grief, without hunger, without thirst’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 8.7.1.3), ‘Who is omniscient, all-knowing’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.9; 2.2.7), ‘The knower of Brahman attains the highest’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.1), ‘Brahman, verily, is all this’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 2.5.1-14, 14 times) and so on.

(Prima facie view.)

An objection may be raised here:—The entire Veda is but a collection of five kinds of texts, called, injunction, prohibition, explanation or eulogy, sacred formulae and name.[17] Of these, ‘One, who desires heaven should perform the Jyotiṣṭoma[18] sacrifice’ and so on, are injunctive texts. ‘A Brāhmaṇa should not be killed’ and so on, are prohibitive texts. ‘The wind, verily, is the quickest deity’ (Taittirīya-saṃhitā 2.1.1[19]), and so on are explanations or eulogisms, ‘Oblation to you’ (Taittirīya-saṃhitā 1.1.1[20]), ‘O, heavens, having the fire as your head’ (Ṛg-veda-saṃhitā 8.44.16a;[21] Śatapatha-brāhmaṇa 2.3.4.11a[22]), and so on are sacred formulae. ‘Jyotiṣṭoma’,[23] ‘Aśvamedha’[24] and the rest are names,—thus we distinguish them. Thus, in the beginning, in the aphorism: ‘Then, therefore, an enquiry into religious duties’ (Pūrva-mīmāṃsā-sūtra 1.1.1[25]), it is said that the Veda has meaning as possessing the fruit to he attained through the injunctions regarding conceptions which are instrumental to the Vedic studies. In the second aphorism which is concerned with mark, viz. ‘A religious duty has injunction for its mark’ (Pūrva-mīmāṃsā-sūtra 1.1.2[26]), it is established, on the ground of the vyāpti: ‘Whatever has the Veda for its proof, refers to action’, that in the sphere of religious duties, injunction is the authority.[27] Here a doubt arises as to whether the artha-vāda-texts like ‘The wind is the swiftest deity’ (Taittirīya-saṃhitā 2.1.1[28]) are authoritative in the sphere of religious duties, or not. With regard to it, the prima facie view is as follows: We have a text: ‘Since Scripture is concerned with action, there is purportlessness of what does not refer to it (viz. action)’ (Pūrva-mīmāṃsā-sūtra 1.2.1[29]). (It means:)—‘Scripture, i.e. the Veda, is ‘kriyārtha’, i.e. has ‘action’ alone as its ‘purport’, or subject-matter or topic,—for this reason, the artha-vāda-texts are not authoritative. What then are they?—anticipating this question, the text goes on to say that ‘there is purportlessness of what does not refer to it’, i.e. let there be simply ‘purportlessness’ or ‘meaninglessness’ of that which has not ‘action’ for its ‘purport’, viz. of artha-vāda and the rest, and in the very same manner, of the Vedānta-texts as well. Even those (Vedānta-) texts which comprise injunctions regarding study: viz. ‘One’s own text should be studied’, cannot be reasonably said to be authoritative, since they are (really) concerned with Brahman, leading to no fruit.[30]

(Here ends the prima facie view within the original prima facie view.)

With regard to this, we state the correct conclusion: ‘Because of their unanimity with the injunctions, let (them be authoritative) through having the glorification of injunctions as their purport’ (Pūrva-mīmāṃsā-sūtra 1.2.7[31]). That is, since the artha-vādas are unanimous with the injunctive texts, let them be authoritative ‘through having glorification as their purport’, i.e. by way of glorifying the matters to be enjoined. Similarly, in order to prevent the absolute purportlessness of the Vedānta-texts which are wanting in injunction and prohibition and teach an accomplished object (viz. Brahman), it is reasonable to take them too as indirectly connected with action,—which is something to be accomplished,—as included under the very mantras and artha-vādas, since they (viz. the Vedānta-texts) admit injunctions regarding the study of the Veda. But if they be taken to be independent (of action) they would lead to no fruit, and hence they must be understood to have fulfilled their purpose through establishing the agent, who is a part of a sacrifice (and not to be independent of action). Among these, the texts concerning the ‘that’ (viz. Brahman) and ‘thou’ (viz. the individual soul)[32] glorify the deity and the agent of the sacrificial act; and the knowledge concerning it (viz. the ‘that’) called the ‘higher knowledge’,[33] glorify the fruit. (Thus, we conclude:) The Vedānta-texts are not concerned with Brahman, but are like the artha-vāda-texts, since they are concerned with proclaiming the excellence of the agent, who is a subordinate factor in a sacrifice. (Here ends the original prima facie view.[34])

(Author’s conclusion.)

To this we reply:[35] No, because this is a mere imagination, invented by you; and because (on the contrary), works, being generative of knowledge which is a means to salvation, indirectly refer to Brahman alone, as declared by the scriptural text:—‘The Brāhmaṇas desire to know this self through the study of the Veda, through sacrifice, through penance, through fasting’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 4.4.22). Here, if in the statement ‘They desire to know through sacrifice’, there be a direct connection of the instrument, viz. ‘sacrifice’, with the meaning of the root,[36] as in the sentence ‘He desires to go by the horse’, then the sacrificial act should be known to be serving the purpose of knowledge (i.e. helping the rise of knowledge), and thereby referring to Brahman. If, on the other hand, owing to the primacy of the desiderative suffix,[37] there he a connection with the meaning of the suffix, it should be known to be serving the purpose of desire, (i.e. helping the rise of a desire for knowledge), to be a subordinate factor of knowledge through that desire and to be referring to Brahman thereby. And, the fact that action is a part of knowledge will be stated under the aphorism: ‘And, there is dependence on all, on account of the text concerning sacrifice, as in the case of a horse’ (Brahma-sūtra 3.4.26).

It cannot be said, also, that the reality to be known from the Vedānta (viz. Brahman) is a subordinate factor of sacrifices,—since He is self-dependent as the controller of all works, their agents and their instruments. Nor can it he said that the Vedānta-texts are subsidiary parts of injunctions like the artha-vādas, since the former have been referred to in a different context and are not in proximity to injunctions. Nor can it he said that the Vedānta-texts lead to no fruit, teaching, as they do, something which is neither an, injunction nor a prohibition,—since the knowledge of Brahman, who is to be known from the Vedānta, leads to a supremely excellent fruit, viz. salvation.

If it be said: As we read in texts like ‘Undecaying, verily, is the good deed of one who performs the Cātur-māsya[38] sacrifice’ (Āp.Ś.Ś. 8.1.1.1[39]) that works too have the same fruit like it (viz. knowledge), so there is nothing objectionable (in taking the scriptural texts) to be referring to works,—

(We reply:) No, because the scriptural text: ‘Just as here, the world gained through work perishes, so exactly does hereafter the world gained through merit perish’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 8.1.6[40]) is of a greater force; is in conformity with the inference, viz. ‘The world gained through mere work is non-permanent, because it is gained through work alone, as in the case of tilling and the rest’; and is confirmed by another scriptural text as well, viz. ‘Frail, indeed, are these boats of sacrifices’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.2.7); because the text: ‘Undecaying, verily’ (Āp.Ś.Ś. 8.1.1) and so on is a weaker one; and because it is improper to (take the scriptural texts) to he referring to works, which form the object of such texts wanting in force. On the other hand, the tests: ‘Those who know this, become immortal’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 4.4.14; Kaṭha 6.2.9; Śvetāśvatara-upaniṣad 3.1.10.13; 4.17.20), ‘The knower of Brahman attains the highest’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.1), are not contradicted by any scriptural text, and cannot be set aside by a thousand inferences. Further, the text: ‘Undecaying, indeed’ and so on (Āp.Ś.Ś. 8.1.1) is not really set aside, since it refers to the relative (permanence of works)[41], and since the holy Bhāgavata-smṛti (i.e. the Bhāgavad-gītā), which is a version of the Veda, is the authority in both the cases (viz. regarding the nonpermanence of karma, and the permanence of Brahman) thus:—‘“The worlds, beginning from the world of Brahman, come and go, O Arjuna! But, on attaining me, O Son of Kuntī! there is no re-birth”’ (Gītā 8.16).

If it be objected: It may he that the Upaniṣadic portion is somehow or other concerned with Brahman, since we see it to be so. But the prior portion (viz. the Karma-kāṇḍa) is known from the texts: ‘He performs the Agnihotra[42] as long as he lives’, ‘One who desires heaven should perform the Jyotiṣṭoma sacrifice’ (Āp. Ś.Ś. 10.2.1) and so on, to fulfil its purpose by enjoining obligatory and optional works and the rest; and hence how can they be concerned with Brahman?—

(We reply:) Not so. The entire Veda is concerned only with Brahman, and although some part of it is found to refer to action somehow, its complete concordance is found in Brahman alone. Among these the Upaniṣadic portion refers directly to Brahman, directly concerned, as it is, with demonstrating His nature, attributes and the rest. Among these, again, the statements of difference refer to Brahman by way of being concerned with the nature of the sentient, the non-sentient and Brahman; the statements of non-difference, by being concerned with proving that everything has Brahman for its essence; the statements of creation and the rest, by being concerned with proving attributes like creatorship and the rest; the statements that Brahman is non-qualified, by being concerned with the denial of the qualities due to māyā; the statements that Brahman is qualified, by being concerned with proving the natural qualities of the Lord; and the statements like: ‘That which is not manifested through speech’ (Kena 1.4), by being concerned with proving that Brahman is not limited by so-muchness.

The texts, concerned with the daily and occasional duties,[43] too, refer to Brahman alone, by way of effecting the purification of the nature of the person entitled (to the study of Brahman) and being thereby co-operative towards the rise of knowledge and so on concerning Brahman; while (the texts) concerned with the optional duties,[44] by way of being an atomic bit of the bliss of Brahman, since the text: ‘Other beings subsist on a portion only of His bliss alone’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 4.3.32) declares even worldly pleasure to be an atomic portion of the bliss of Brahman. Moreover, the optional duties are in concordance (with regard to Brahman), since they are concerned with the knowledge of Brahman by way of giving rise to a pure body, like that of a god and the rest, entitled to salvation. Moreover, just as in accordance with the maxim of ‘connection and disconnection’,[45] curd, used in connection with daily duties (nitya),—as laid down in the passage: ‘He performs a sacrifice with curd’,—brings about the attainment of objects of sense,—as laid down in the passage: ‘One who desires for objects of sense should perform a sacrifice with curd’ (Taittirīya-brāhmaṇa 2.1.5.6[46]),—so the sacrificial acts, though bringing about heaven and the rest, should yet be known to be serving the purpose (i.e. helping the rise) of knowledge.[47] And (finally) texts like: ‘Golden right from the tip of His nails’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 1.6.6[48]) refer to Brahman as being concerned with His divine body.

Or else, since the entire mass of objects has Brahman for its essence, the mass of texts, denoting them, directly refer to Him.[49]

Hence it is established that the entire Veda is in concordance with regard to Brahman alone or Lord Kṛṣṇa the Highest Person, omniscient, possessing infinite natural and inconceivable powers, the cause of the world, and different and non-different from the sentient and the non-sentient, as declared by the Lord Himself in the passage: ‘“By all the Vedas, I alone am to be known”’ (Gītā 15.15).

The four aphorisms constituting the basis of Scripture are hereby explained. This treatise (viz. the Vedānta) is but an expounding of these.

Here ends the section entitled ‘Concordance’ (4).

Here ends the explanation of the four aphorisms in the first quarter of the first chapter in the commentary Vedānta-kaustubha, composed by the reverend teacher Śrīnivāsa, the incarnation of the Pāñcajanya and dwelling under the lotus-feet of the reverend Lord Nimbāditya, the founder of the sect of the reverend Sanatkumāra.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

An artha-vāda is the explanation of the meaning of a precept, or eulogism.

[2]:

The sense of the objection is: All Vedas set forth injunctions or prohibitions with regard to action. Bat besides the texts which directly or explicitly set forth the above, there are in the Vedas some texts which are merely indicative, and not injunctive. And, these latter kind of texts are to be explained, not literally, but as eulogising the direct injunctive texts and thereby indirectly forming a part of injunctions, etc., otherwise the integrity of the Vedas cannot be maintained. Hence, the Vedanta-texts too must be taken as not establishing Brahman, but as simply extolling the sacrificer by identifying him with the Supreme Soul and so on, and as such really concerned with sacrificial acts.

[3]:

That is, the proper function of karmas is simply to purify the mind, and thereby create a desire for knowledge. Karma, thus, is a means and not an end, the way to truth and not truth itself. Hence the Vedanta-texts, dealing as they do, with the Supreme Truth, cannot be concerned with mere karmas. Vide Vedānta-pārijata-saurabha 3.4.26.

[4]:

I.e. knowledge is not an aṅga of karma, on the contrary, karma is an aṅga of knowledge. Vide Vedānta-pārijata-saurabha 3.4.8.

[5]:

Viz. Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 4.4.22.

[6]:

Vide Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 5.6.1; Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1-4.

[7]:

Vide Chāndogya-upaniṣad 5.5.4-10. Also Vedānta-kaustubha 3.1.1.

[8]:

Vide Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 2.5.1-19 (whole section); Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.1-11.

[9]:

Vide e.g. Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 5.7-9, etc.; Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.18-21; 7.1-12, etc.

[10]:

The sense is that the various kinds of texts may impel a man to different procedures. Some may lead a man to meditate on Brahman directly as the self, others to meditate on Him as the sun and so on.

[11]:

That is, even the texts concerning the various meditations and symbols, are to be understood as directly referring to Brahman, i.e. to be interpreted literally, and not as referring to Brahman indirectly, i.e. to be interpreted figuratively, as suggested before. This modifies the statement made immediately before that some texts are direct and primary, some indirect and secondary, and takes all to be equally direct and primary.

[13]:

That is, the view that all texts are concerned with Brahman directly in no way precludes the negative texts, since these negative texts also are concerned with Brahman equally.

[14]:

P. 36, vol. 1.

[15]:

P. 19. Reading: ‘Yatraikaṇ’.

[16]:

P. 181.

[18]:

[19]:

P. 125, lines 1-2, vol. 1.

[20]:

P. 1, line 1, vol. 1.

[21]:

P. 132, line 7.

[22]:

P. 163, line 16.

[23]:

See footnote 4, above.

[24]:

The horse-sacrifice.

[25]:

P. 1, vol. 1.

[26]:

P. 3, vol. 1.

[27]:

That is, the inference is as follows:—

Whatever has the Veda for its proof, refers to action.

A religious duty has the Veda for its proof.

* a religious duty refers to action, i.e. is concerned with injunctions and prohibitions.

[28]:

P. 125, lines 1-2, vol. 1.

[29]:

p. 39, vol. 1.

[30]:

That is, there are some Vedānta-texts, which do refer to action, i.e. to injunction, yet they are not to be taken as authoritative, since they really refer to Brahman who is outside the sphere of actions and fruits.

[31]:

P. 42, vol. 1.

[32]:

Cf. the famous text ‘Thou art that’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.8.7, etc.).

[33]:

Vide e.g. Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.4-5.

[34]:

It began on p. 35.

[35]:

The correct conclusion begins here.

[36]:

Viz. ‘vid’—to know.

[37]:

Viz. ‘san’, imply ing ‘desire’.

[38]:

See footnote 2, p. 5.

[39]:

P. 1, vol. 1.

[40]:

Correct quotation: ‘Karma-cita’ and not ‘karma-jita’, which is translated here. Vide Chāndogya-upaniṣad 8.1.6, p. 415.

[41]:

That is, this text simply shows that the deeds of one who performs the Cātur-māsya sacrifice are relatively more permanent than the deeds of one who does not, and not that they are absolutely permanent.

[42]:

Sacrificing to Agni. Cf. Atharvaveda-saṃhitā 6.97.1, p, 130.

[43]:

The daily or nitya karmas are ablution, prayer and so on, to be performed every day; while the occasional or naimittaka karmas are the ceremony in honour of the dead and so on, to be performed on special occasions. Both of these kinds are obligatory.

[44]:

The optional or kāmya karmas are sacrifices and the rest, undertaken with special objects in view, viz. heaven and the rest.

[45]:

A term applied to express the disconnection of what is optional from what is a necessary constituent of anything. Vide Pūrva-mīmāṃsā-sūtra 4.3.5, and Śabara’s commentary, pp. 493 and ff., vol. 1.

[46]:

P. 180, line 3, vol. 2.

[47]:

Vide Vedānta-kaustubha 3.4.26.

[49]:

That is, instead of the laborious explanation given above, it is simpler to accept this alternative explanation.