Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

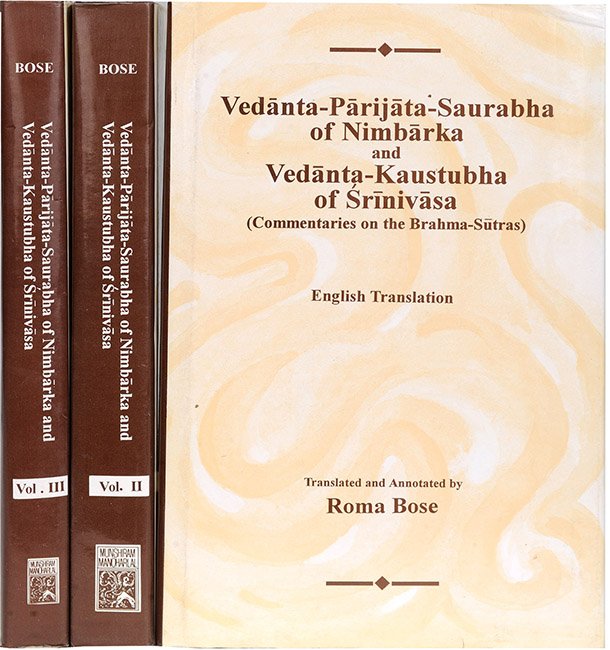

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra Preface, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Preface

Nimbārka’s commentary on the Brahma-Sūtras known as the Vedānta-Parijāta-Saurabha, and that of his immediate disciple Śrīnivāsa styled the Vedānta-Kaustubha are the chief works of the school of philosophy associated with the name of Nimbārka. The latter is not, however, a mere commentary on the former, as is sometimes wrongly supposed, but a full exposition of the views expressed in the Vedānta-Parijāta-Saurabha which is very terse and concise and is not always clear. Both the treatises are therefore essential for the proper understanding of the doctrine of Nimbārka.

Hitherto no translation of either of these works was available in the English language, and the task was undertaken by Dr. Roma Bose (Chaudhuri) at the suggestion of Prof. F. W. Thomas, Boden Professor of Sanskrit in the University of Oxford, under whose supervision it was carried out during 1934-1936, as part of the thesis for the Degree of D. Phil. of that University.

This authoritative English Edition of the Vedānta-Parijāta-Saurabha has been prepared after carefully comparing the manuscripts Nos. E164, 2480, 2481 and 3273 of the India Office Library and the printed Sanskrit texts of the Kāśī, Brindāban and Chowkhāmbā Series. The translation of the Vedānta-Kaustubha was based on the Sanskrit texts of the Kāśī and Brindāban editions. Differences of readings of the various manuscripts and printed texts of both the treatises have been noted in the footnotes.

As is well-known the doctrine of Advaita, as developed by Śaṃkara, was the earliest of the Vedāntic systems, and in the great efflorescence of philosophic thought in India during the 9th-16th centuries, various schools of thought arose, mostly as protests against the extreme views held by the Advaita school. There is no doubt that by reason of its great metaphysical appeal and the rigid application of logical canons, Śaṃkara’s Advaita-vāda exercised the most profound influence on Indian thought and marked him out as the greatest philosophical genius born in this country. His insistence, however, on the sole reality of ‘Abheda’ or non-difference and the unreality of Bheda or difference evoked strong reactions, the foremost of which was the Viśiṣṭādvaita-vāda of Rāmānuja, whose importance was only second to that of Śaṃkara. According to him the reality is not an abstract concept in the Śaṃkarite sense in which the non-difference completely loses its identity, but is a synthetic unity of both—the relation between the two being that of the substance-attribute. That is, the attribute is different from the substance in the sense that it inheres in it though the latter cannot be equated with any particular attribute and is not a mere assemblage of them all, but is something over and above. In other words, the substance and the attribute, or the unity and plurality are both real and form an organic whole, and the relation between them is the relation of non-difference, and not of absolute identity. Rāmānuja’s doctrine is hence known as Viśiṣṭādvaita-vāda or qualified monism as against the absolutism of Śaṃkara.

Śrīkaṇṭha, who followed Rāmānuja, agreed that the relation between the Brahman and the Universe was that of non-difference, but while the latter identified Brahman with Viṣṇu, according to Śrīkaṇṭha it was Śiva. His theory is therefore called Viśiṣṭa-Śivādvaita-vāda.

The school of Bhāskara holds that both the unity and plurality are real. The relation between the two is one of difference-non-difference during the effected state of Brahman, i.e. during the cosmic existence and creation, but one of complete identity during the causal state of Brahman, i.e. during salvation and dissolution. In other words, the individual Soul or Jīva, during the state of Saṃsāra, is different from Brahman due to the presence of the Upādhis (limiting adjuncts) such as the body, the sense organs, etc., but when these are not present and it is Mūkta, the Jīva becomes absolutely identical with Brahman of which it is only the effect. Similarly, the world is both different and non-different from Brahman during creation, but identical with Him in Pralaya (dissolution). Hence Bhāskara’s view is known as ‘Aupādhika-Bhedābheda-vāda’, i.e. the Bhedābheda relation between Brahman and the Universe is only Aupādhika or due to the limiting adjuncts only and therefore lasts as long as these adjuncts last. But when the Saṃsāra is over and the Upādhis are no more, there is no longer any Bhedābheda between Brahman and the Universe, the former alone becomes the reality and no separate soul or matter can then exist.

Baladeva’s school also admitted the reality of both the unity and plurality. In a sense, both the Jīva and the Jagat are different from Brahman but in another they are non-different as effects of Brahman. This relation of difference-non-difference is transcendental and cannot be comprehended by reason and must be accepted on the authority of the Scriptures (revelation). His doctrine goes, therefore, under the name of ‘Acintya-Bhedābheda-vāda’, i.e. the Bhedābheda relation of Brahman and the Universe is Acintya or incomprehensible by reason.

The doctrine of Nimbārka, which developed in the atmosphere of general reaction against Śaṃkara’s Advaitism, shared the views of the above schools in their insistence on the reality of the Many. According to Nimbārka, Brahman and Jīva-Jagat are equally real as was also held by Rāmānuja, but the difference between them is not superseded by non-difference as the latter supposed. In fact, the difference between the two is just as significant as their non-difference. While it is true, as Rāmānuja thought, that the Jīva-Jagat or the entire universe inheres in the unity of Brahman as an organic whole and as such can lay no claim to separate existence, yet as the effect is different from the cause, in the same sense is the Many different from the One, and their difference is as fundamental as their non-difference. Nimbārka’s system has therefore been called the Svābhāvika-Bhedābheda-vāda in which the relation between Brahman and the Jīva-Jagat is regarded as one of eternal difference-non-difference during Saṃsāra or the cosmic existence as well as Pralaya or dissolution, and not only during the former state as Bhāskara thought. According to his view even the freed Soul (Mūkta-Jīvātman) is both different and non-different from Brahman and even in Pralaya does the Jagat inhere in Brahman as a distinct entity.

In her English rendering of the Vedānta-Pārijāta-Saurabha and Vedānta-Kaustubha, Dr. Bose has not only given Nimbārka’s reading and interpretation of each Sūtra, but has compared them with those of Śaṃkara, Rāmānuja, Śrīkaṇṭha, Bhāskara and Baladeva belonging to the antagonistic and allied schools of the Yedānta Philosophy. Differences from the religious and ethical grounds have not either been ignored. The present work therefore is not to be considered as a mere translation, but it gives also reviews of the main tenets of the post-Śaṃkara theistic schools which arose in opposition to Advaita-Vedāntism, though the full philosophical exposition of Nimbārka’s doctrine and the comparative study of the development of Indian thought during this period has been discussed by her in a separate work which will form the third and concluding volume of this series.

The work consists of four chapters. In Chapter I (Samanvayādhyāya), it is sought to establish that Brahman is the sole subject of all Scriptures. The nature of Brahman, His attributes and the sources of our knowledge of Him are discussed in this chapter. In Chapter II (Avirodhādhyāya), Nimbārka first refutes the rival views of Sāṃkhya-Yoga, Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, Buddhism, Jainism, Śaivaism and Śāktaism, and considers the problems of Jīva and Jagat, their natures and attributes and the manner in which they are related to Brahman. These two chapters are purely metaphysical and supply the philosophical foundations of the doctrine of Nimbārka. The remaining ones are chiefly of devotional and ethical interests. In Chapter III (Sādhanādhyāya), for example, the means of attaining Mokṣa (salvation), the nature and importance of meditations as mentioned in the Upanishads are discussed. In Chapter IV (Phalādhyāya), Nimbārka gives his views on Mokṣa, the fruit and the conditions of the Mūkta (released) Jīvātman or soul, etc. According to him Mokṣa or salvation implies two conditions, namely, the attainment of qualities and nature similar to Brahman (Brahma-Svarūpa-lābha), and the full development of one’s own individuality (Ātma-Svarūpa-lābha). This full development means the complete manifestation of one’s real nature as consciousness (Jñāna-Svarūpa) and bliss (Ānanda), untainted and unimpeded by matter which screens it during Saṃsāra, and deceives it into believing that it is self-sufficient and independent of Brahman. When, however, Mokṣa is attained, it is realized that it is dependent on Brahman as His organic part and in that sense non-different from Him. It implies the destruction of narrow egoity, hut not the annihilation of individuality as is the goal of the Advaita school. Nimbārka’s ideas on Mokṣa or salvation therefore are the logical outcome of his theistic mind which seeks to find a place for the devotional soul without completely merging it in Brahman.

The first two chapters containing the metaphysical portion of the work is now issued as Volume I consisting of 474 pages. Volume II will comprise the remaining two chapters and indexes for both the volumes. The latter is expected also to be published during this year.

29th February, 1940.

B. S. GUHA,

General Secretary,

Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal.