Bhagavad-gita-rahasya (or Karma-yoga Shastra)

by Bhalchandra Sitaram Sukthankar | 1935 | 327,828 words

The English translation of the Bhagavad-Gita Rahasya, also known as the Karma-yoga Shastra or “Science of Right Action”, composed in Marathi by Bal Gangadhar Tilak in 1915. This first volume represents an esoteric exposition of the Bhagavadgita and interprets the verses from a Mimamsa philosophical standpoint. The work contains 15 chapters, Sanskri...

Chapter 8 - The Construction and the Destruction of the Cosmos

guṇā guṇeṣu jāyante tatraiva niviśanti ca |

—Mahābhārata, Śānti. (305.23)."Constituents (guṇas) are born out of constituents, and are merged in them".

I have so far dealt with the nature of the two independent fundamental principles of the world according to the Kapila Sāṃkhya philosophy, namely. Matter and Spirit, and have described how one has to release one's Self from the network of the constituent qualities of Matter which it places before one's eyes, as a result of its union with Spirit. But the explanation of how this 'Saṃsāra' (worldly illusion) is placed by Matter before the Spirit–this its diffusion, or its drama which Marathi poets have given the vivid name of 'saṃsṛticā piṃgā' (the fantastic dance of worldly life), and which is called "the Mint of Matter" by Jñāneśvara Mahārāja–and in what way the same is destroyed, has still to be given; and I shall deal with that subject in this chapter. This activity of Matter is known as "the Construction and Destruction of the Cosmos", because, according to the Sāṃkhya philosophy, prakṛti (Matter) has created this world or creation for the benefit of in- numerable Spirits. Śrī Samartha Rāmdāsa has in two or three places in the Dāsabodha given a beautiful description of how the entire Cosmos is created from Matter, and I have taken the phrase "Construction and Destruction of the Cosmos" from that description. Similarly, this subject-matter has been dealt with principally in the seventh and eighth chapters of the Bhagavadgītā, and from the following prayer of Arjuna to Śrī Kṛṣṇa in the beginning of the eleventh chapter, namely: "bhavāpyayau hi bhūtanāṃ śrutau vistaraśo mayā" (Bhagavadgītā 11.2), i.e., "I have heard (what You have said) in detail about the creation and the destruction of created beings; now show me actually Your Cosmic Form, and fulfill my ambition", it is clearly seen that the construction and the destruction of the Cosmos is an important part of the subject-matter of the Mutable and the Immutable. The Knowledge by which one realises that all the perceptible objects in the world, which are more than one (are numerous), contain only one fundamental imperceptible substance, is called 'jñāna' (Bhagavadgītā 18.20); and the Knowledge by which one understands how the various innumerable perceptible things severally camo into existence out of one fundamental imperceptible substance is called 'vijñāna'; and not only does this subject-matter include the consideration of the Mutable and the Immutable, but it also includes the knowledge of the Body and the Ātman and the knowledge of the Absolute Self.

According to the Bhagavadgītā, Matter does not carry on its activities independently, but has to do so according to the will of the Parameśvara (Bhagavadgītā 9.10). But, as has been stated before, Kapila Ṛṣi considered Matter as independent. According to the Sāṃkhya philosophy, its union with Spirit is a sufficient proximate cause for its diffusion to commence. Matter needs nothing else for this purpose. The Sāṃkhyas say that as soon as Matter is united with Spirit, its minting starts; and just as in spring, trees get foliage and after that, leaves, flowers, and fruits follow one after the other (Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 231.73; and Manu-Smṛti 1.30), so also is the fundamental equable state of Matter disrupted, and its constituents begin to spread out.

On the other hand, in the Veda-Saṃhitās, the Upaniṣads, and the Smṛti texts, the Parabrahman is looked upon as fundamental instead of Matter, and different descriptions are found in those books about the creation of the Cosmos from that Parabrahman (Highest Brahman), namely that:

"hiraṇyagarbhaḥ samavartatāgre bhūtasya jātaḥ patir eka āsīt",

I.e., "the Golden Egg first came into existence" (Ṛg-veda 10.121.1).

And from this Golden Egg, or from Truth, the whole world was created (Ṛg-veda 10.72; 10.190); or first, water was created (Ṛg-veda 10.83.6; Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa 1.1.3.7; Aitareyopaniṣad 1.1.2), and from that water, the Cosmos; or that when in this water an egg had come into existence, the Brahmadeva was born out of it, and either from this Brahmadeva, or from the original Egg, the entire world was later on created (Manu-Smṛti 1.8–13; Chāndogyopaniṣad 3.19); or that the same Brahmadeva (male) was turned, as to half of him, into a female (Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣad 1.4.3; Manu-Smṛti 1.32); or that Brahmadeva was a male before water came into existence (Kaṭhopaniṣad 4.6); or that from the Parabrahman only three elements, were created, namely, brilliance, water and the earth (food), and that later on, all things were created as a result of the intermixture of the three (Chāndogyopaniṣad 6.2–6). Nevertheless, there is a, clear conclusion in the Vedānta-Sūtras (Vedānta-Sūtras 2.3.1–15), that the five primordial elements, namely. Ether (ākāśa) etc., came into existence in their respective order from the fundamental Brahman in the shape of the Ātman (Taittirīya Upaniṣad 2. 1); and there are clear references in the Upaniṣads to prakṛti, mahat, and Other elements, e. g., see Kaṭha (3.11), Maitrāyaṇī (6.10), Śvetāśvatara (4.10; 6.16) etc. From this it can be seen that though according to Vedānta philosophy, Matter is not independent, yet after the stage when a transformation makes its appearance in the Pure Brahman in the shape of an illusory Prakṛti, there is an agreement between that philosophy and the Sāṃkhya philosophy about the subsequent creation of the Cosmos; and it is, therefore, stated in the Mahābhārata that: "all knowledge which there is in history or in the Purāṇas, or in economics has all been derived from Sāṃkhya philosophy" (Śān. 301.108, 109). This does not mean that the Vedāntists or the writers of the Purāṇas have copied this knowledge from the Kapila Sāṃkhya philosophy; but only that everywhere the conception of the order in which the Cosmos was created is the same. Nay, it may even be said that the word 'Sāṃkhya' has been used here in the comprehensive meaning of 'Knowledge'. Nevertheless, Kapilācārya has explained the order of the creation of the Cosmos in a particularly systematic manner from the point of view of a science, and as the Sāṃkhya theory has been principally accepted in the Bhagavadgītā, I have dealt with it at length in this chapter.

Not only have modern "Western materialistic philosophers accepted the Sāṃkhya doctrine that the entire perceptible Cosmos has come out of one avyakta (imperceptible to the organs), subtle, homogeneous, unorganised, fundamental substance, which completely pervades everything on all sides, but they have come to the further conclusions that the energy in this fundamental substance has grown only gradually, and that nothing has come into existence suddenly and like a spout, giving the go-bye to the previous and continuous order of creation of the universe. This theory is called the Theory of Evolution. When this theory was first enunciated in the Western countries in the last century, it caused there a great commotion. In the Christian Scriptures, it is stated that the Creator of the world created the five primordial elements and every living being which fell into the category of moveables one by one at different times, and this genesis was believed in by all Christians before the advent of the Evolution Theory. Therefore, when this doctrine ran the risk of being refuted by the Theory of Evolution, that theory was attacked on all sides, and that opposition is still more or less going on in those countries. Nevertheless, in as much as the strength of a scientific truth must always prevail, the Evolution Theory of the creation of the Cosmos is now becoming more and more acceptable to all learned scholars. According to this theory, there was originally one subtle, homogeneous substance in the Solar system, and as the original motion or heat of that substance gradually became less and less, it got more and more condensed, and the Earth and, the other planets gradually came into existence, and the Sun is the final portion of it which has now remained. The Earth was originally a very hot ball, same as the Sun, but as it gradually lost its heat, some portion of the original substance remained in the liquid from, while other portions became solidified, and the air and water which surround the earth and the gross, material earth under them.

'Came gradually into existence; and later on, all the living and non-living creation came into existence as the result of the union, of these three. On the line of this argument, Darwin and other philosophers have maintained that even.man has in this way gradually come into existence by evolution from microorganisms. Yet, there is still a great deal of difference of opinion between Materialists and Meta-physicians as to whether or not the Soul (Ātman) should be considered as an independent fundamental principle. Haeckel -and some others like him maintain that the Soul and Vitality have gradually come into existence out of Gross Matter, and support the jaḍādvaita (Gross Monistic) doctrine; on the other hand, Metaphysicians like Kant say that in as much as all the knowledge we get of the Cosmos is the result of the synthetic activity of the Soul, the Soul must be looked upon as an independent entity. Because, saying that the Soul which perceives the external world is a part of the world which is perceived by it, or that it has come into existence out of the world, is logically as meaningless as saying that one can sit on one's own shoulders. For the same reason, Matter and Spirit are looked upon as two independent principles in the Sāṃkhya philosophy. In short, it is even now being maintained by many learned scholars in the Western countries that however much the Materialistic knowledge of the universe may grow, the consideration of the form of the Root Principle of the Cosmos must always be made from a different point of view. But my readers will see that as regards the question of the order in which all perceptible things came to be created from one Gross Matter, there is not much difference of opinion between the Western Theory of Evolution, and the Diffusion- out of Matter described in the Sāṃkhya philosophy; because, the principal proposition that the heterogeneous perceptible Cosmos (both subtle and gross) came to be gradually created from one imperceptible, subtle, and homogeneous fundamental Matter, is accepted by both. But, as the knowledge of the Material sciences has now considerably increased, modern natural scientists have considered as prominent the three qualities of motion, heat and attraction, instead of the three qualities of sattva, rajas, and tamas of the Sāṃkhya philosophy.

It is true that from the point of view of the natural sciences, it is easier to realise the diversity in the mutual strength of heat or attraction than the diversity in the mutual intensity of the three qualities of sattva, rajas, and tamas. Nevertheless,, the principle: " guṇā guṇeṣu, vartante" (Bhagavadgītā 3.28), i.e., "constituents come out of constituents", which is the principle of the diffusion or expansion of constituent qualities, is common to both. Sāṃkhya philosophers say that in the same way as a folding-fan is gradually opened out, so also when the folds of Matter in its equable state (in which its sattva, rajas, and tamas constituent qualities are equal) are opened out, the whole perceptible universe begins to come into- existence; and there is no real difference between this conception and the Theory of Evolution. Nevertheless, the fact that the Gītā, and partly also the Upaniṣads and other Vedic texts have without demur accepted the theory of the growth of the guṇas (constituents) side by side with the Monistic Vedānta doctrines, instead of rejecting it as is done by the Christian religion, is a difference which ought to be kept in mind from the point of view of the Philosophy of Religion.

Let us now consider what the theory of the Sāṃkhya philosophers is about the order in which the folds of Matter are un-folded. This order of unfoldment is known as 'guṇotkarṣa-vāda' (the theory of the unfolding of constituent qualities), or 'guṇā- pariṇāma-vāda' (the theory of the development of qualities). It need not be said that every man comes to a decision according to his own intelligence to perform an act or that he must first get the inspiration to do an act, before he commences to do the act. Nay, there are statements even in the Upaniṣads, that the universe came to be created after the One fundamental Paramātman was inspired with the desire to multiply, e.g., "bahu syāṃ prajāyeya" (Chāndogyopaniṣad 6.2.3; Taittirīya Upaniṣad 2.6). On the same line of argument, imperceptible Matter first comes to a decision to break up its own equable state and to create the perceptible universe. Decision means 'vyavasāya', and coming to a decision is a sign of Reason. Therefore, the Sāṃkhya philosophers have come to the conclusion that the first quality which comes into existence in Matter is Pure (deciding) Reason (vyavasāyātmikā buddhi). In short, in the same way as a man has first to be inspired with the desire of doing some particular act, so also is it necessary that Matter- should first be inspired with the desire of becoming diffuse. But because man is vitalised, that is to say, because in him there has taken place a union between the Reason of Matter and the vitalised Spirit (Ātman), he understands this deciding Reason which inspires him; and as Matter itself is non-vital or Gross, it does not understand its own Reason. This is the great difference between the two, and this difference is the result of the Consciousness which Matter has acquired as a result of its union with the Spirit. It is not the quality of Gross Matter. When one bears in mind that even modern Materialistic natural scientists have now begun to admit that unless one credits Matter with some Energy which, though non-selfintelligible (asvayaṃvedya), is yet of the same nature as human intelligence, one cannot reasonably explain the mutual attraction or repulsion seen in the material world in the shape of gravitation, or magnetic attraction or repulsion, or other chemical actions,[1] one need not be surprised about the proposition of the Sāṃkhya philosophy that Reason is the first quality which is acquired by Matter. You may, if you like, give this quality which first arises in Matter the name of Reason which is non-vitalised or non-self-perceptible (asvayaṃvedya)., But it is clear that the desire which a man gets and the desire which inspires Matter belong originally to one and. the same class; and, therefore, both are defined in the same way in both the places. This Reason has also such other names as 'mahat', 'jñāna', 'mati', 'āsurī ', 'prajña', 'khyāti' etc. Out of these, the name 'mahat' (first person singular masculine, mahān, i.e., ' big ') must have been given because Matter now begins to be enlarged, or on account of the importance of this quality. In as much as this quality of 'mahān' or Reason is the result of the admixture of the three constituent qualities of sattva, rajas, and tamas, this quality of Matter can later on take diverse forms, though apparently it is singular. Because, though the sattva, rajas and tamas constituents are apparently only three in number, yet, in as much as the mutual ratio of these three can be infinitely different in each mixture, the varieties of Reason which result from the infinitely different ratios of each constituent in each mixture can also be infinite. This Reason, which arises from imperceptible Matter, is also subtle like Matter. But although Reason is subtle like Matter, in the sense in which the words 'perceptible', 'imperceptible', 'gross', and 'subtle' have been explained in the last chapter, yet it is not imperceptible like Matter, and one can acquire Knowledge of it. Therefore, this Reason falls into the category of things which are 'vyakta' (i.e., perceptible to human beings); and not only Reason, but all other subsequent evolutes (vikāra) of Matter are also looked upon as perceptible in the Sāṃkhya philosophy. There is no imperceptible principle other than fundamental Matter.

Although perceptible Discerning Reason thus enters imperceptible Matter, it (Matter) still remains homogeneous. This homogeneity being broken up and heterogeneity being acquired is known as 'Individuation' (pṛthaktva) as in the case of mercury falling on the ground and being broken up into small globules. Unless this individuality or heterogeneity comes into existence, after Reason has come into existence, it is impossible that numerous different objects should be formed out of one singular Matter. This individuality which subsequently arrives as a result of Reason is known as 'Individuation' (ahaṃkāra), because, individuality is first expressed by the words 'I–you', and saying 'I–you' means 'ahaṃkāra', that is, saying 'aham' 'aham' ('I' 'I'). This quality of Individuation which enters Matter may, if you like, be called a non-self-perceptible (asvayaṃvedya) Individuation, But the Individuation in man, and the Individuation by reason of which trees, stones, water, or other fundamental atoms spring out of homogeneous Matter are of the same kind; and the only difference is that as the stone is not self-conscious, it has not got the knowledge of 'aham' ('I'), and as it has not got a mouth, it cannot by self-consciousness say 'I am different from you'. Otherwise, the elementary principle of remaining separate individually from others, that is, of consciousness or of Individuation is the same everywhere. This Individuation has also the other names of 'taijasa', 'abhimāna', 'bhūtādi, and 'dhātu'. As Individuation is a sub-division of Reason it cannot come into existence, unless Reason has in the first instance come into existence. Sāṃkhya philosophers have, therefore, laid down that Individuation is the second quality, that is, the quality which comes into existence after Reason. It need not be said that there are infinite varieties of Individuation as in the case of Reason, as a result of the differences of the sattva, rajas and tamas constituents. The subsequent qualities are in the same way also of three infinite varieties. Nay, everything which exists in the perceptible world falls in the same way into infinite categories of sāttvika, rājasa and tāmasa; and consistently with this proposition, the Gītā has mentioned the three categories of qualities and the three categories of Devotion (Bhagavadgītā Chap. 14 & Chap. 17).

When Matter, which originally is in an equable state, acquires the perceptible faculties of Discerning Reason and Individuation, homogeneity is destroyed and it begins to be transformed into numerous objects. Yet, it does not lose its subtle nature, and we may say that the subtle Atoms of the Nyāya school now begin to come into existence. Because, before Individuation came into existence, Matter was unbroken and unorganised. Reason and Individuation by themselves are, strictly speaking, only faculties. But, on that account the above proposition is not to be understood as meaning that they exist independently of the substance of Matter. What is meant is, that when these faculties enter the fundamental, homogeneous, and organised Matter, that Matter itself acquires the form of perceptible, heterogeneous, and organised substance. When fundamental Matter has thus acquired the faculty of becoming transformed into various objects by means of individualization, its further development falls into two categories. One of these is the creation consisting of life having organs, such as trees, man etc., and its other is of the world consisting of unorganised things. In this place the word 'organs' is to be understood as meaning only "the faculties of the organs of organised beings". Because, the gross body of organised beings is included in the gross, that is, unorganised world, and their 5lman falls into the different category of 'Spirit'. Therefore, in dealing with the organised world, Sāṃkhya philosophy leaves out of consideration the Body and the Atman, and considers only the organs. In as much as there can be no third substance in the world besides organic and inorganic substances, it goes without saying that Individuation cannot give rise to more than two categories. As organic faculty is more powerful than inorganic substance, the organic world is called sāttvika, that is, something which comes into existence as a result of the preponderance of the sattva constituent; and the inorganic world is called tāmasa, that is something which comes into existence as a result of the preponderance of the tamas constituent. In short, when the faculty of Individuation begins to create diverse objects, there is sometimes a preponderance of the sāttvika constituent, leading to the creation of the five organs of Perception, the five organs of Action, and the Mind, making in all the eleven fundamental organs of the organic world; and at other times, there is a preponderance of the tamas constituent, whereby the five fundamental Fine Elements (tanmātra) of the inorganic world come into existence. But in as much as Matter still continues to remain in a subtle form, these sixteen elements, which are a result of Individuation, are still subtle elements[2]

The Fine Elements (tanmātras) of sound, touch, colour, taste and smell–that is to say, the extremely subtle fundamental forms of each of these properties which do not mix with each other–are the fundamental elements of the inorganic creation, and the remaining eleven organs, including the Mind, are the seeds of the organic creation. The explanation given in the Sāṃkhya philosophy as to why there are -only five of the first kind and only eleven of the second kind deserves consideration. Modern natural scientists have divided the substances in the world into solid, liquid, and gaseous. But the principle of classification of substances according to Sāṃkhya philosophy is different. Sāṃkhya philosophers say that man acquires the knowledge of all worldly objects by means of the five organs of Perception; and the peculiar construction of these organs is such that any one organ perceives only one quality. As the eyes cannot smell, the ears cannot see, the skin cannot distinguish between sweet and bitter, the tongue does not recognise sound, and the nose cannot distinguish between black and white. If the five organs of Perception and their five objects, namely, sound, touch, sight, taste, and smell, are in this way fixed, one cannot fix the number of the properties of matter at more than five. Because, even if we imagine that there are more than five such properties, we have no means to perceive them. Each of these five objects of sense can of course be sub-divided into many divisions. For example, though sound is only one object of sense, yet, it is divided into numerous kinds of sound, such as small, large, harsh, hoarse, broken or sweet; or, as described in the science of music, it may be the note B or E or C etc.; or according to grammar, it may be guttural, palatal, labial etc.; and similarly, though taste is in reality only one object of sense, yet, it is also divided into many kinds such as, sweet, pungent, saltish, hot, bitter, astringent, acid etc.; and although colour is in reality only one object of sense, it is also divided: into diverse colours such as white, black, green, blue, yellow, red etc.; similarly even if sweetness is taken as a particular kind of taste, yet. the sweet tastes of sugarcane, milk, jaggery, or sugar are all different divisions of sweetness; and if one makes different mixtures of different qualities, this diversity of qualities becomes infinite in an infinite number of ways. But, whatever happens, the fundamental properties of substance can never be more than five; because, the organs of

Perception are only five in number and each of them perceives only one object of sense. Therefore, although we do not come across any object which is an object of sound only or of touch only, that is, in. which different properties are not mixed up, yet, according to- Sāṃkhya philosophy, there must be fundamentally only five distinct subtle tanmātra modifications of fundamental. Matter, namely, merely sound, merely touch, merely colour, merely taste, and merely smell–that is, the fine sound element (śabda-tanmātra), the fine touch element (sparśa-tanmātra), the fine colour element (rūpa -tanmātra), the fine taste element (rasa-tanmātra) and the fine smell element (gandha-tanmātra), I have further on dealt with what the writers of the Upaniṣads have to say regarding the five Fine Elements or the five primordial elements springing from them.

If, after having thus considered the inorganic world and come to the conclusion that it has only five subtle fundamental; elements, we next consider the organic world, we likewise come; to the conclusion that no one has got more than eleven organs, namely, the five organs of Perception, the five organs of Action and the Mind. Although we see the organs of hands, feet etc., only in their gross forms in the Gross Body, yet, the. diversity of the various organs cannot be explained, unless we admit the existence of some subtle element at the root of each of them. The western Materialistic theory of Evolution bas- gone into a considerable amount of discussion on this question. Modern biologists say that the most minute fundamental' globular micro-organisms have only the organ of skin, and that from that skin other physical organs have come into' existence one by one. They say, for instance, that the eye came into existence as a result of the contact of light with the skin of the original micro-organism; and that, similarly, the other gross organs came into existence by the contact of light etc.

This doctrine of Materialistic philosophers is to be found even in Sāṃkhya philosophy. In the Mahābhārata there is a description of the growth of the organs consistent with the tenets of Sāṃkhya philosophy, as follows:–

śabdarāgāt śrotram asya jāyate bhāvitātmanaḥ |

rūparāgāt tathā cakṣuḥ ghrāṇaṃ gandhajighṛkṣayā ||

(Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 313.16).

That is, "When the Ātman in a living being gets the desire of hearing sound, the ears come into existence; when it gets the desire of perceiving colour, the eyes are formed; when it gets the desire of smelling, the nose is created".

But the Sāṃkhya philosophers say that though the skin may be the first thing- to come into existence, yet, how can any amount of contact of the Sun's rays with the skin of micro-organisms in the living world give rise to eyes–and that too in a particular portion of the body–unless fundamental Matter possesses an inherent possibility of different organs being created? Darwin's theory only says that when one organism with eyes and another organism without eyes have been created, the former lives longer than the latter in the struggle for existence of the material world, and the latter is destroyed. But the Western Materialistic science of biology does not explain why in the first place the eyes and other physical organs at all come into existence. According to the Sāṃkhya philosophy, these various organs do not grow one by one out of one fundamental organ, but when Matter begins to become heterogeneous as a result of the element of Individuation, such Individuation causes the eleven different faculties or qualities, namely, the five organs of Perception, the five organs of Action and the Mind, to come into existence in fundamental Matter, independently of each other and simultaneously (yugapat); and thereby, later on, the organic world comes into existence. Out of these eleven organs, the Mind is dual, that is, it performs two different functions, according to tie difference in the organs with which it works, as has been explained before it the sixth chapter: that is to say, it is discriminating and classifying (saṃkalpa-vikalpātmaka) in co-operation with the organs of Perception and arranges tie various impressions experienced by tie various organs, end after classifying them. places them before Reason for decision; and it is executive (vyākaraṇātmaka) in co-operation with tie organs of Action, that is to say, it executes tie decisions, arrived at by Season with the help of tie organs of Action. In the Upaniṣads, the organs themselves are given the name of 'Vital Force' (prāṇa); and the authors, of the Upaniṣads (Muṇḍa 2.1.3), like the Sāṃkhya philosophers, are of the opinion that these vital forces are not the embodiment of tie five primordial elements, but are individually born out of the Paramātman (Absolute Self). Tie number of these vital forces or organs is stated in the Upaniṣads to be seven in some places and to be ten, eleven, twelve, or thirteen in other places; but Śrī Śaṃkarācārya has proved on the authority of the Vedānta- Sūtras, that if an attempt is made to harmonise the various statements in the Upaniṣads, the number of these organs is fixed at eleven (Śāṃkarabhāṣya 2.4.5, 6); and in the Gītā, it has been clearly stated that "indriyāṇi daśaikaṃ ca" (Bhagavadgītā 13.5), i.e., "the organs are ten plus one, or eleven". In short, there is no difference of opinion on this point between the Sāṃkhya and the Vedānta philosophy.

According to the Sāṃkhya philosophy, after the eleven organic faculties or qualities, which are the basis of the organic world, and the five subtle elementary essences (tanmātras) which are the basis of the inorganic world have thus come into existence as a result of sāttvika and tāmasa Individuation respectively, the five gross primordial elements (which are also called 'viśeṣa'), as also gross inorganic substances, come into.existence out of the five fundamental subtle essences (tanmātras); and when these inorganic substances, come into contact with the eleven subtle organs, the organic universe comes into existence.

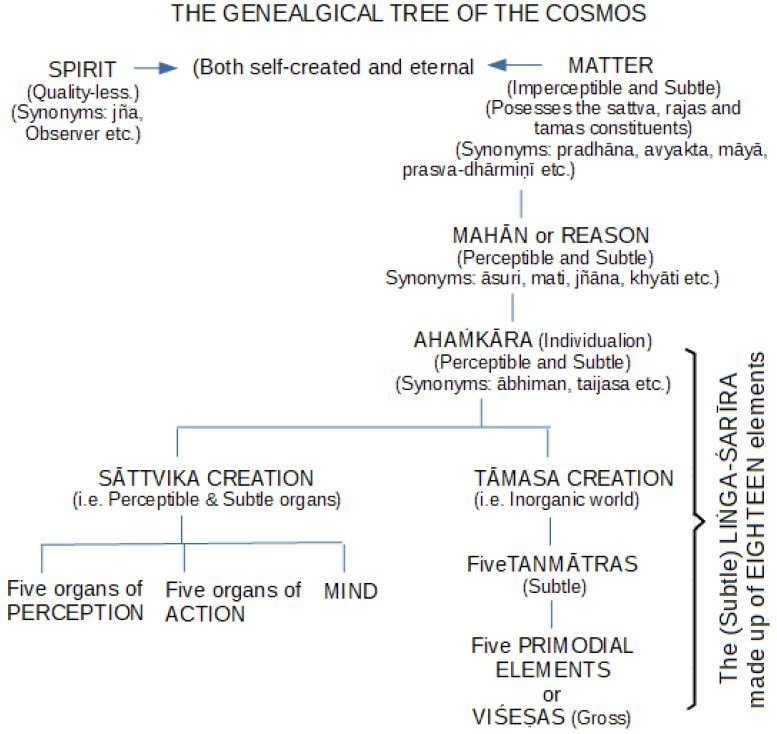

The order in which the various Elements come out of fundamental Matter according to Sāṃkhya philosophy, and which has been so far described, will be clear from the genealogical tree given below:–

There are thus twenty-five elementary principles, counting the five gross primordial elements and Spirit. Out of these, the twenty-three elements including and after Mahān (Reason), are the evolutes (vikāras) of fundamental Matter. But even then, the subtle Tanmātras and the five gross primordial elements are substantial (dravyātmaka) evolutes and Reason. Individuation, and the organs are merely faculties or qualities. The further distinction is that whereas these twenty-three elements are perceptible, fundamental Matter is imperceptible. Out of these twenty-three elements, Cardinal Directions (east, west etc.,) and Time are included by Sāṃkhya philosophers in Ether (ākāśa), and instead of looking upon Vital

Force (prāṇa) as independent, they give the name of Vital Force to the various activities of the organs, when these activities have once started (Sāṃkhya Kārikā 29). But this opinion is not accepted by Vedāntists, who consider Vital Force as an independent element (Vedānta-Sūtras 2.49). Similarly, as has been stated before, Vedāntists do not look upon either Matter or Spirit as self-created and independent, but consider them to be two modifications (vibhūti) of one and the same Parameśvara. Except for this difference between the Sāṃkhyas and the Vedāntists, the other ideas about the order of creation of the Cosmos are common to both.

For instance, the following description of the Brahmavṛkṣa or Brahmavana, which has occurred twice in the Anugītā in the Mahābhārata (Śriman Mahābhārata Aśva. 35.20–23 and 47.12–15) is in accordance with the principles of Sāṃkhya philosophy:–

avyaktabījaprabhavo buddhiskabandhamayo mahān |

mahāhaṃkāravitapaḥ indriyāntarakotaraḥ ||

mahābhutaviśākhāś ca viśeṣapratiśākhavān |

sadāparṇaḥ sadāpuṣpaḥ śubhāśubhaphalodayaḥ ||

ājīvyaḥ sarva bhūtānām brahmavṛkṣaḥ sanātanaḥ |

enam chittvā ca bhittvā ca tattvajñānāsinā budhaḥ ||

hitvā sañgamayān pāśān mṛtyujamnajarodayān |

nirmamo nirahaṃkāro mucyate nātra saṃśayaḥ ||

That is: "the Imperceptible (Matter) is its seed, Reason (mahān) is its trunk, Individuation (ahaṃkāra) is its principal foliage, the Mind and the ten organs are the hollows inside the trunk, the (subtle) primordial elements (the five tanmātras) are its five large branches, and the Viśeṣas or the five Gross primordial elements are its sub-branches, and it is always covered by leaves, flowers, and auspicious or inauspicious fruit, and is the fundamental support of all living things; such is the ancient gigantic Brahmavṛkṣa. By cutting it with the philosophical sword and chopping it up into bits, a scient should destroy the bonds of Attachment (saṅga) which cause life, old age, and death, and should abandon the feeling of mine-ness and individuality; in this way alone can he be released".

In short, this Brahmavṛkṣa is nothing but the 'dance of creation' or the 'diffusion' of Matter or of Illusion. The practice of referring to it as a 'tree' is very ancient and dates from the time of the Ṛg-veda, and it has been called by the name 'the ancient Pipal Tree' (sanātana aśvatthavṛkṣa) in the Upaniṣads (Kaṭhopaniṣad 6.1). But there, that is, in the Vedas, the root of this tree (Parabrahman) is stated to be above and the branches (the development of the visible world) to be below. That the description of the Pipal tree in the Gītā has been made by harmonising the principles of Sāṃkhya philosophy with the Vedic description has been made clear in my commentary on the 1st and 2nd stanzas of the 15th chapter of the Gītā.

As the Sāṃkhyas and the Vedāntists classify in different ways the twenty-five elements described above in the form of a tree, it is necessary to give here some explanation about this classification. According to the Sāṃkhyas, these twenty-five elements fall into the four divisions of (i) fundamental prakṛti, (ii) prakṛti-vikṛti, (iii) vikṛti and [iv) neither prakṛti nor vikṛti. (1) As Prakṛti is not created from anything else, it is called fundamental prakṛti (Matter). (2) When you leave this fundamental Matter and come to the second stage, you come to the element Mahān. As Mahān springs from Prakṛti, it is said to be a vikṛti or an evolute of fundamental Matter; and as later on, Individuation comes out of the Mahān element, this Mahān is the prakṛti or root of Individuation. In this way this Mahān (Reason) becomes the prakṛti or root of Individuation on the one hand, and the vikṛti (evolute) of the fundamental Prakṛti (Matter) on the other hand. Therefore, Sāṃkhya philosophers have classified it under the heading of 'prakṛti-vikṛti'; and in the same way Individuation (ahaṃkāra), and the five Tanmātras are also classified under the heading of 'prakṛti-vikṛti'. That element which, being itself horn out of some other element, i.e., being a vikṛti, is at the same time the parent (prakṛti) of the subsequent element is called a 'prakṛti-vikṛti'. Mahat (Reason) Individuation, and the five Tanmātras, in all seven, are of this kind. (3) But the five organs of Perception, the five organs of Action, the Mind, and the five Gross primordial elements, which are in all sixteen, give birth to no further elements. On the other hand, they themselves are born out of some element or other. Therefore, these sixteen elements are not called 'prakṛti-vikṛti', but are called 'vikṛti' (evolutes). (4) The Spirit (Puruṣa) is neither prakṛti nor vikṛti; it is an independent and apathetic observer.

This classification has been made by Īśvarakṛṣṇa, who has explained it as follows:–

mūlaprakṛtir avikṛtiḥ mahadādyāḥ prakṛtivikṛtayaḥ sapta |

ṣoḍaṣakastu vikāro na prakṛtir na vikṛtiḥ puruṣaḥ ||

That is: "The fundamental Prakṛti is 'a-vikṛti', that is, it is the vikāra (evolute) of no other substance; Mahat and the others, in all seven–Mahat, Ahaṃkāra and the five Tanmātras are prakṛti-vikṛti and the eleven organs, including the Mind, and the five gross primordial elements, making in all sixteen, are called merely vikṛti or vikāra (evolutes). The Puruṣa (Spirit) is neither a prakṛti nor a vikṛti" (Sāṃkhya Kārikā 3).

And these twentyfive elements are again classified into the three classes of Imperceptible, Perceptible and Jña. Out of these, fundamental Matter is imperceptible, the twenty-three elements, which have sprung from Matter are perceptible, and the Spirit is 'Jña'. Such is the classification according to Sāṃkhya philosophy, In the Purāṇas, the Smṛtis, the Mahābhārata and other treatises relating to Vedic philosophy, these same twenty-five elements are generally mentioned (See Maitryupaniṣat (or Maitrāṇyupaniṣad) 6. 10: Manu 1, 14, 15). But in the Upaniṣads, it is stated that all these are created out of the Parabrahman, and there is no further discussion or classification. One comes across such classification in treatises later than the Upaniṣads, but it is different from the Sāṃkhya classification mentioned above.

The total number of elements is twenty-five. As sixteen elements out of these are admittedly Vikṛtis, that it, as they are looked upon as created from other elements, even according to Sāṃkhya philosophy, they are not classified in these treatises as prakṛti or fundamental substances. That leaves nine elements:–(l) Spirit, (2) Matter, (3–9) Mahat, Ahaṃkāra and the five subtle elements (Tanmātras). The Sāṃkhyas call the last seven, after Spirit and Matter, 'prakṛtivikṛti'. But according to Vedānta philosophy, Matter is not looked upon. as independent. According to their doctrine, both Spirit and Matter come out of one Parameśvara (Absolute Īśvara). If this proposition is accepted, the distinction made by Sāṃkhya philosophers between fundamental Prakṛti and prakṛti-vikṛti comes to an end; because, as Prakṛti itself is looked upon as having sprung from the Parameśvara, it cannot be called the Root, and it falls into the category of 'prakṛtivikṛti'. Therefore, in describing the creation of the Cosmos, Vedānta philosophers say that from the Parameśvara there spring on the one hand the Jīva (Soul), and on the other hand, eight-fold Prakṛti (i.e., Prakṛti and seven prakṛti-vikṛtis, such as Mahat etc.,) (Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 306.29, and 310.10). That is to say, according to Vedānta philosophers, keeping aside sixteen elements out of twenty-five, the remaining nine fall into the two classes of 'Jīva' (Soul) and the 'eight-fold Prakṛti'. This classification of Vedānta philosophers has been accepted in the Bhagavadgītā; but therein also, a small distinction is ultimately made. What the Sāṃkhyas called 'Puruṣa' is called 'Jīva' by the Gītā, and the Jīva is described as being the 'parāprakṛti' or the most sublime form of the Īśvara, and that which the Sāṃkhyas call the 'fundamental Prakṛti' is referred to in the Gītā as the 'apara' or inferior form of the Parameśvara (Bhagavadgītā 7.4, 5). When in this way, two main divisions have been made, then, in giving the further sub-divisions or kinds of the second main division, namely, of the inferior form of the Īśvara, it becomes necessary to mention the other elements which have sprung from this inferior form, in addition to that inferior form. Because, the inferior form (that is, the fundamental Prakṛti of Sāṃkhya philosophy) cannot be a kind or subdivision of itself. For instance, when you have to say how many children a father has, you cannot include the father in the counting of the children. Therefore, in enumerating the subdivisions of the inferior form of the Parameśvara, one has to exclude the fundamental Prakṛti from the eight-fold Prakṛti mentioned by the Vedāntists, and to say that the remaining seven, that is to say, Mahān, Ahaṃkāra, and the five Fine Elements are the only kinds or sub-divisions of the fundamental Prakṛti; but if one does this, one will have to say that the inferior form of the Parameśvara, that is, fundamental Prakṛti is of seven kinds, whereas, as mentioned above, Prakṛti is of eight kinds according to the Vedāntists. Thus, the Vedāntists will say that Prakṛti is of eight kinds, and the Gītā will say that Prakṛti is of seven kinds, and an apparent conflict will come into existence between the two doctrines. The author of the Gītā, however, considered it advisable not to create such a conflict, but to be consistent with the description of Prakṛti as 'eight-fold'. Therefore, the Gītā has added the eighth element, namely, Mind, to the seven, namely Mahān, Ahaṃkāra, and the five Fine Elements, and has stated that the inferior form of the Parameśvara is of eight kinds (Bhagavadgītā 7.5). But, the ten organs are included in the Mind, and the five primordial elements are included in the five Fine Elements. Therefore, although the classification of the Gītā, may seem different from both the Sāṃkhya and the Vedantic classification, the total number of the elements is not, on that account, either increased or decreased. The elements are everywhere twenty-five. Yet, in order that confusion should not arise as a result of this difference in classification, I have shown below these three methods of classification in the form of a tabular statement. In the thirteenth chapter of the Gītā (13.5), the twenty-five elements of the Sāṃkhyas are enumerated one by one, just as they are, without troubling to classify them; and that shows that though the classification may be different, the total number of the elements is every- where the same:–

Classification of the Twenty-five Fundamental elements:

| Sāṃkhya classification | Elements | Vedānta classification | Gītā classification |

| (1) Neither Prakṛti nor vikṛti | 1 SPIRIT | (1) The Superior form of Parabrahman | (1) parā Prakṛti |

| (1) Fundamental Prakṛti | 1 PRAKṚTI | (8) The inferior form of Parabrahman (eight-fold). | (1) aparā Prakṛti |

| (7) Prakṛti-vikṛti | 1 Mahā; 1 Ahaṃkāra; 5 Tanmātras |

(8) There are eight subdivisions of the aparā Prakṛti. | |

| (16) Vikāras | 1 MIND; 5 Organs of Perception; 5 Organs of Action; 5 Primordial Elements 25 |

(16) These sixteen Elements are not looked upon as Fundamental Elements by Vedāntists as they are (evolutes). | (15) These fifteen Elements are not looked upon as Fundamental Elements by the Gītā, as they are (evolutes). |

I have thus concluded the description of how the homogeneous, inorganic, imperceptible, and gross Matter, which was fundamentally equable, acquires organic heterogeneity as a result of Individuation after it has become inspired by the non-self-perceptible 'Desire' (buddhi) of creating the visible universe, and also how, later on, as a result of the principle of the Development of Constituents (guṇapariṇāma), namely that, "'Qualities spring out of qualities" (guṇā guṇeṣu jāyante), the eleven sāttvika subtle elements, which are the fundamental elements of the organic world come into existence on the one hand, and the five subtle Fine Elements (tanmātras), which are the fundamental elements of the tāmasa world come into existence on the other hand. I must now explain in what order the subsequent creation, namely, the five gross primordial elements, or the other gross material substances which spring from them, have come into existence. Sāṃkhya philosophy only tells us that the five gross primordial elements or Viśeṣas have come out of the five Fine Elements, as a result of guṇa-pariṇāma. But, as this matter has been more fully dealt with in Vedānta philosophy, I shall also, as the occasion has arisen, deal with that subject-matter, but after warning my readers that this is part of Vedānta philosophy and not of Sāṃkhya philosophy. Gross earth, water, brilliance, air and the ether are called the five primordial elements or Viśeṣas.

Their order of creation has been thus described in the Taittirīyopaniṣad:–

ātmanaḥ ākāśaḥ saṃbhūtaḥ | ākāśād vāyuḥ | vāyor agniḥ | agner āpaḥ | adabhyaḥ pṛthivī | pṛthivyā oṣadhayaḥ | etc.

(Taittirīya Upaniṣad 2.1).

From the Paramātman, (not from the fundamental Gross Matter as the Sāṃkhyas say), ether was first created; from ether, the air; from the air, the fire; from the fire, water; and from water, later on, the earth has come into being. The Taittirīyopaniṣad does not give the reason for this order. But in the later Vedānta treatises, the explanation of this order of creation of the five primordial elements seems to be based on the guṇapariṇāma principle of the Sāṃkhya system. These later Vedānta writers say that by the law of "guṇa guṇeṣu vartante" (qualities spring out of qualities), a substance having only one quality first conies into existence, and from that substance other substances having two qualities, three qualities etc., subsequently come into existence. As ether out of the five primordial elements has principally the quality of sound only, it came into existence first. Then came into existence the air, because, the air has two qualities, namely, of sound and touch. Not only do we hear the sound of air, but we feel it by means of our organ of touch. Fire comes after the air, because, besides the qualities of sound and touch, it has also the third quality of colour. As water has, in addition to these three qualities, the quality of taste also, water must have come into existence after fire; and as the earth possesses the additional quality of smell besides these four qualities,, we arrive at the proposition that the earth must have sprung' later on out of water. Yāska has propounded this very doctrine (Nirukta 14.4).

The Taittirīyopaniṣad contains the further description that when the five gross primordial elements had come into existence in this order,

pṛthivyā oṣadhayaḥ | oṣadhibhyo 'nnam | annāt puruṣaḥ |

(Taittirīya Upaniṣad 2.1),

I.e., "from the. earth have grown vegetables; from the vegetables, food; and from food, man.”

This subsequent creation is the result of the mixture of the Ave primordial elements, and the process of that mixture is called ' pañcī-karaṇa' in the Vedānta treatises. Pañcī-karaṇa means the coming into existence of a new substance by the mixture of different qualities of each of the five primordial elements.

This union of five (pañcī-karaṇa) can necessarily take place in an indefinite number of ways. In the ninth daśaka (collection of ten verses each) of the Dāsabodha, it is stated:–

By mixing black and white |

we get the grey colour |

By mixing black and yellow |

we get the green colour ||

(9. 6. 40)

And in the 13th daśaka, it is stated as follows:

In the womb of that earth |

there is a collection of an infinite number of seeds ||

When water gets mixed with the earth |

sprouts come out ||

Creepers of variegated colours |

with waving leaves and flowers are next born ||

After that come into existence |

fruits of various tastes ||

… … … … … … …

The earth and water are the root |

of all oviparous, viviparous, steam-engendered, and vegetable life

Such is the wonder |

of the creation of the universe ||

There are four classes and four modes of voice |

eighty-four lakhs[3] of species of living beings ||

Have come into existence in the three worlds |

which is the Cosmic Body ||

(Dāsabodha 13.3.10–15).

This description in the Dāsabodha given by Samartha Rāmadāsa is based on this idea. But it must not be forgotten that by the union of five (pañcīkaraṇa) only gross objects or gross bodies come into existence, and this gross body must become united first with subtle organs and next with the Ātman or the Spirit before it becomes a living body.

I must also make it clear here that this union of five, which has been described in the later Vedānta works, is not to be found in the ancient Upaniṣads. In the Chāndogyopaniṣad, these Tanmātras or primordial elements are not considered to be five; but brilliance, water and food (earth) are the only three which are considered as subtle fundamental elements, and the entire diverse universe is said to have come into existence by the mixture of these three, that is, by 'trivṛtkaraṇa'; and it is stated in the Śvetāśvataropaniṣad that: "ajām ekaṃ lohitaśuklakṛṣṇāṃ bahvīḥ prajāḥ sṛjamānāṃ sarūpāḥ" (Śvetāśvataropaniṣad 4.5), i.e., "this she-goat (ajā) is red, or of the nature of fire; and white, or of the nature of water; and black, or of the nature of earth; and is thus made of three elements of three colours, and from it all creation (prajā) embodied in Name and Form has been created". In the 6th chapter of the Chāndogyopaniṣad has been given the conversation between Śvetaketu and his father. In it, the father of Śvetaketu clearly tells him: "O, my son I in the commencement of the world, there was nothing except 'ekam evādvitīyaṃ sat' (single and unseconded sat), that is to say, nothing else except one homogeneous and eternal Parabrahman. How can 'sat' (something which exists) come into existence out of 'asat' (something which does not exist)? Therefore, in the beginning sat pervaded everything. Then that sat conceived the desire of becoming multifarious, that is, heterogeneous, and from it grew one by one, brilliance (tejas) water (āpa) and food (pṛthivī) in their subtle forms. Then, after the Parabrahman had entered these three elements in the form of Life, all the various things in the universe which are identified hy Name and Form came into existence as a result of the union of those three (trivṛtkaraṇa). The red (lohita) colour, which is to be found in the gross fire or the Sun or in electricity, is the result of the subtle fundamental element of brilliance; the white (śukla) colour, of the fundamental subtle element of water; and the black (kṛṣṇa) colour, of the fundamental subtle element of earth. In the same way, subtle fire, subtle water, and subtle food (pṛthivī) are the three fundamental elements which are contained even in the food which man eats. Just as butter comes to the surface when you churn curds, so when this food, made up of the three subtle elements enters the stomach, the element of brilliance in it, creates gross, medium and subtle products in the shape of bones, marrow and speech respectively; and similarly, the element of water (āpa) creates: urine, blood and Vital Force; and the element of earth (pṛthivī) creates the three substances, excrement, flesh and mind" (Chāndogyopaniṣad 6.2–6). This system of the Chāndogyopaniṣad of not taking the primordial elements as five, but as only three, and of explaining the creation of all visible things by the union of these three substances (trivṛtkaraṇa) has been mentioned in the VedāntaSūtras (2.4.20), and Bādarāyaṇācārya does not even mention the word 'Pañcīkaraṇa'. Nevertheless, in the Taittirīya (2.1), Praśna (4.8), Bṛhadāraṇyaka (4.4.5) and other Upaniṣads, and in the Śvetāśvatara itself (2.12) and in the Vedānta-Sūtras (2. 3. 1–14) and lastly in the Gītā (7.4; 13.5), five primordial elements are mentioned instead of three; and in the Garbhopaniṣad, the human body is in the very beginning stated to be 'pañcātmaka', that is, made up of five; and the Mahābhārata and the Purāṇas give clear descriptions of Pañcīkaraṇa (Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 184–186). From this it becomes quite clear, that the idea of the 'union of five' (pañcīkaraṇa) becomes ultimately acceptable to all Vedānta philosophers and that although the 'union of three' (trivṛtkaraṇa) may have been ancient, yet, after the primordial elements came to be believed to be five instead of three, the idea of Pañcīkaraṇa was based on the same sample as the Trivṛtkaraṇa, and the theory of Trivṛtkaraṇa went out of vogue. Not only is the human body formed of the five primordial elements, but the meaning of the word Pañcīkaraṇa has been extended to imply that each one of these five is divided in five different ways in the body. For instance, the quinary of skin, flesh, bone, marrow, and muscles grows out of earth etc. etc. (Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 186.20–25; and Dāsabodha 17.8). This idea also seems to have been inspired by the description of Trivṛtkaraṇa in the Chāndogyopaniṣad mentioned above. There also, there is a statement at the end that brilliance, water, and earth are each to be found in three different forms in the human body.

The explanation of how the numerous inactive (acetana), that is to say, lifeless or gross objects in the world, which can be distinguished by Name and Form, came into existence out of the fundamental imperceptible Matter–or according to the Vedānta theory, from the Parabrahman–is now over. I shall now consider what more the Sāṃkhya philosophy tells us about the creation of the sacetana (that is, active) beings in the world, and later on, see how far that can be harmonised with the Vedānta doctrines. The body of living beings comes into existence when the five gross primordial elements sprung from the fundamental Matter are united with the subtle organs. But though this body is organic, it is still gross. The element which activates these organs is distinct from Gross Matter and it is known as Spirit (puruṣa). I have, in the previous 'chapter, mentioned the various doctrines of the Sāṃkhya philosophy that this Spirit is fundamentally inactive, that the living world begins to come into existence when this Spirit is united with fundamental Matter, and that when the Spirit acquires the knowledge that "I am different from Matter", its union with Matter is dissolved, failing which it has to peregrinate in the cycle of birth and death. But as I have not, in that chapter, explained how the Ātman–or according to Sāṃkhya terminology, the Puruṣa–of the person, who dies without having realised that the Ātman is different from Matter, gets one birth.after another, it is necessary now to consider that question more in detail. It is quite clear that the Ātman of the man who dies without having acquired Self-Realisation does not escape entirely from the meshes of Matter; because, if such were the case, one will have to say with Cārvāka, that every man escapes from the tentacles of Matter or attains Release immediately after death; and Self-Realisation or the difference between sin and virtue will lose its importance. Likewise, if you say that after death, the Ātman or the Spirit alone survives, and that it, of its own accord, performs the action of taking new births, then the fundamental theorem that Spirit is inactive and apathetic, and that all the activity is of Matter is contradicted. Besides, by acknowledging that the Ātman takes new births of its own accord, you admit that to be its property and fall into the impossible position that it will never escape from the cycle of birth and death. It, therefore, follows that though a man may have died without having acquired SelfRealisation, his Ātman must remain united with Matter, in order that Matter should give it new births. Nevertheless, as the Gross Body is destroyed after death, it is quite clear that this union cannot continue to be with Matter composed of the five gross primordial elements. But it is not that Matter consists only of the five gross primordial elements. There are in all twenty-three elements which arise out of Matter, and the five gross primordial elements are the last five out of them.

When these last five elements (the five primordial elements) are subtracted from the twenty-three, eighteen elements remain, It, therefore, follows as a natural conclusion that though a man, who dies without having acquired SelfRealisation escapes from the Gross Body made up of the five gross primordial elements, that is to say, from the last five elements, yet, his death does not absolve him from his union with the remaining eighteen elements arising out of Matter. Reason (Mahān) Individuation, Mind, the ten organs, and the five Fine Elements are these eighteen elements. (See the Genealogical tree of the Cosmos given at page 243). All these elements are subtle. Therefore, that Body which is formed as a result of the continued union of Spirit (puruṣa) with them is called the 'Subtle Body', or the 'Liṅga-śarīra' as the opposite of the Gross Body or 'Sthūla-śarīra' (Sāṃkhya Kārikā 40). If any person dies without having acquired Self-Realisation, this his Subtle Body, made up of the eighteen elements of Matter, leaves his Gross Body on his death along with the Ātman, and compels him to take birth after birth. To this, an objection is raised by some persons to the following effect: when a man dies, one can actually see that the activities of Reason, Individuation, Mind, and the ten organs come to an end in his Gross Body along with life; therefore, these thirteen elements may rightly be included in the Subtle Body; but there is no reason for including the five Fine Elements in the Subtle Body along with these thirteen elements. To this the reply of the Sāṃkhya philosophers is, that the thirteen elements, pure Reason, pure Individuation, the Mind and the ten organs are only qualities of Matter, and in the same way as a shadow requires the support of some substance or other, or as a picture requires the support of the wall or of paper, so also must these thirteen elements, which are only qualities, have the support of some substance in order that they should stick together. Out of these, the Ātman (puruṣa), being itself qualityless and inactive, cannot by itself become the support for any quality. When the man is alive, the five gross primordial elements in his body form the support for these thirteen elements. But after his death, that is, after the destruction of the Gross Body, this support in the shape of the five primordial elements ceases to exist. Therefore, these thirteen elements, which are qualities, have to look for some other substance as a support. If you say that they can get the support of fundamental Matter, then, that is imperceptible and in an unevolved condition, that is to say, eternal and all-pervasive; and therefore, it cannot become the support of qualities like Reason etc., which go to form one small Subtle Body. Therefore, the five Fine Elements, which are the bases of the five gross primordial elements, have to be included in the Subtle Body side by side with the thirteen qualities, as a support for them in the place of the five gross primordial elements which are the evolutes of fundamental Matter (Sāṃkhya Kārikā 41). Some writers belonging to the Sāṃkhya school imagine the existence of a third body, composed of the five Fine Elements, intermediate between the Subtle Body and the Gross Body, and maintain that this third body is the support for the Subtle Body. But that is not the correct interpretation of the forty-first couplet of the Sāṃkhya Kārikā, and in my opinion these commentators have imagined such a third, body merely by confusion of thought. In my opinion this couplet has no use beyond explaining why the five Fine Elements have to be included in the Subtle Body along with the thirteen other elements, namely, Reason etc.[4]

Anybody can see after a little thought, that there is not much of a difference between the Subtle Body made up of eighteen elements described in the Sāṃkhya philosophy and the Subtle Body described in the Upaniṣads. It is stated in the Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣad that: "just as a leech (jalāyukā) having reached the end of a blade of grass, places the anterior part of its body on the next blade (by its anterior feet), and then draws up the posterior part, which was placed on the former blade of grass, in the same way, the Ātman leaves one body and enters the other body " (Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣad 4.4.3). But from this single illustration, the two inferences that (i) only the Ātman enters another body and that (ii) it does so immediately after leaving the first body, do not follow. Because, in the Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣad itself, there is another statement further on (Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣad 4.4.5), that the five subtle elements, the Mind, the organs, Vital Force and a man's righteous or unrighteous record, all leave the body along with the Ātman, which goes according to its mundane Actions to different spheres, where it remains for some time. (Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣad 6.2.14 and 15). In the same way, it becomes quite clear from the description of the course followed by Jīva along with the fundamental element of water (āpa) in the Chāndogyopaniṣad (Chan. 5. 3. 3; 5. 9. 1) as also from the interpretation put thereon in the Vedānta-Sūtras (Vedānta-Sūtras 3.1.1–7) that the Chāndogyopaniṣad included the three fundamental elements, viz., water (āpa) and along with it brilliance (tejas) and food (anna) in the Subtle Body. In short, it will be seen that when one adds Vital Force and 'dharmādharma' (i.e., righteous and unrighteous actions) or Karma to.the Sāṃkhya Subtle Body of eighteen elements, one gets the Vedantic Subtle Body. But in as much as Vital Force (prāṇa) is included in the inherent tendencies of the eleven organs, and righteous and unrighteous action (dharmādharma) are included in the activities of Reason and Mind, one may say that this difference is merely verbal, and that there is no real difference of opinion about the components of the Subtle Body between the Vedānta and the Sāṃkhya philosophies. It is for this reason that the description of the Subtle Body According to the Sāṃkhyas as "mahadādi sūkṣmaparyantam" has been repeated, as it is, in the words "mahadādyaviśeṣāntam", in the Maitryupaniṣad (Mai. 6.10).[5] In the Bhagavadgītā, the Subtle Body is described as consisting of "manaḥ ṣaṣṭhānīndriyāṇi" (Bhagavadgītā 15.7), that is, of "the mind and the five organs of Perception"; and further on there is a description that life, in leaving the Gross Body, takes with itself this Subtle Body in the same way as the breeze carries scent from the flowers: "vāyur gandhān ivāśayāt" (Bhagavadgītā 15.8). Nevertheless in as much as the metaphysical knowledge in the Gītā, has been borrowed from the Upaniṣads, one must say that the Blessed Lord has intended to include the five organs of Action, the five Fine Elements, Vital Force, and sin and virtue, in the- words "the six organs including the mind". There is a statement also in the Manu-Smṛti that after a man dies, he acquires a Subtle Body made up of the five Fine Elements in. order to suffer the consequences of his virtuous or evil actions (Manu-Smṛti 12.16, 17). The words "vāyur gandhān ivāśayāt" in the Gītā, prove only that this body must be subtle; but they do not convey any idea as to the size of that body.

But from the statement in the Sāvitryupākhyāna in the Mahābhārata (Śriman Mahābhārata Vana. 296. 16), that Yama took out a Spirit as. large as a thumb from the (gross) body of Satyavāna–"aṃguṣṭhamātraṃ puruṣaṃ niścakarṣa yamo balāt"–it is clear that this Subtle Body was in those days, at least for purposes of illustration, taken to be as big as a thumb.

I have so far considered what inferences lead one to the- conclusion that the Subtle Body exists, though it might be invisible to the eyes, as also what the component parts of that Subtle Body are. But it is not enough to merely say that the Subtle Body is formed by the combination of eighteen elements excluding fundamental Matter and the five gross primordial elements. There is no doubt that wherever this Subtle Body exists, this combination of eighteen elements will, according to its inherent qualities, create gross parts of the body, like hands and feet or gross organs, whether out of the gross bodies of parents, or later on, out of the food in the gross material world; and that it will maintain such a body. But, it remains to be explained why this Subtle Body, made up by the combination of eighteen elements, creates different bodies, such as, animals, birds, men etc. The elements of consciousness in the living world are called 'Puruṣa' by the Sāṃkhyas, and according to them, though these 'Puruṣas' are in- numerable, yet, in as much as each Puruṣa is inherently apathetic and inactive, the responsibility of creating different bodies, such as, birds, beasts etc. cannot rest with the Puruṣa. According to Vedānta philosophy, these differences are said to arise as a result of the sinful or virtuous Actions performed during life. This subject-matter of Karma-Vipāka (the effects caused by Actions) will be dealt with later on. According to Sāṃkhya philosophy, Karma cannot be looked upon as a third fundamental principle which is different from Spirit and Matter; and in as much as Spirit is apathetic, one has to say that Karma (Action) is something evolved from the sattva, rajas, and tamas constituents of Matter. Reason is the most important element out of the eighteen of which the Subtle Body is made up; because, it is from Reason that the subsequent seventeen elements, namely, Individuation, etc. come into existence. Therefore, that which goes under the name of 'Karma' in Vedānta philosophy is referred to in Sāṃkhya philosophy as the activity, property, or manifestation of Reason resulting from the varying intensity of the sattva, rajas and tamas constituents. This property or propensity of Reason is technically called 'Bhāva', and innumerable Bhāvas come into existence as a result of the varying intensity of the sattva, rajas and tamas constituents. These Bhāvas adhere to the Subtle Body in the same way as scent adheres to a flower or colour to cloth (Sāṃkhya Kārikā 40). The Subtle Body takes up new births according to these Bhāvas, or–in Vedāntic terminology–according to Karma; and the elements, which are drawn by the Subtle Body from the bodies of the parents in taking these various births, later on acquire various other Bhavas. The different categories of gods or men or animals or trees, are the results of the combination of these Bhavas (Sāṃkhya Kārikā 43–55). When the sāttvika constituent becomes absolute and preeminent in these Bhāvas, man acquires Self-Realisation and apathy towards the world, and begins to see the difference between Matter and Spirit; and then the Spirit reaches its original state of Isolation (kaivalya), and the Subtle Body being discarded, the pain of man is absolutely eradicated. But, if this difference between. Matter and Spirit has not been realised, and merely the sattva constituent has become predominant, the Subtle Body is reborn, among gods, that is, in heaven; if the rajas quality has become predominant, it is re-born among men, that is, on the earth; and if the tamas quality has become predominant, it is re-born in the lower (tiryak) sphere (Bhagavadgītā 14.18). When in this way it has been re-born among men, the description of how a kalala (state of the embryo a short time after conception), a budbuda (bubble), flesh, muscles, and other different gross organs grow out of a drop of semen has been given in Sāṃkhya philosophy on the basis of the theory of "guṇā guṇeṣu jāyante". (Sāṃkhya Kārikā 43: Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 320). That description is more or less similar to the description given in the Garbhopaniṣad. Although the above-mentioned technical meaning given to the word 'Bhāva' in Sāṃkhya philosophy may not be found in Vedānta treatises, yet, it will be seen from what has been stated above, that the reference by the Blessed Lord to the various qualities "buddhir jñānam asaṃmohaḥ kṣamā satyāṃ damaḥ śamaḥ" by the use of the word 'Bhāva' in the following verse (Bhagavadgītā 10.4, 5; 7.12) must primarily have been made keeping in mind the technical terminology of Sāṃkhya philosophy.

When, in this way, all the living and non-living perceptible things in the universe have come into existence one after the other out of fundamental imperceptible Matter (according to the Sāṃkhya philosophy), or out of fundamental Parabrahman in the form of Sat (according to the Vedānta philosophy), all perceptible things are, both according to the Sāṃkhya and Vedānta philosophies, re-merged either into imperceptible Matter or into fundamental Brahman in a way which is the reverse of the order of development of constituents mentioned above, when the time for the destruction of the Cosmos comes (Vedānta-Sūtras 2.3.14; Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 232); that is to say, earth, out of the five primordial elements, is merged into water, water into fire, fire into air, air into ether, ether into the Fine Elements, the Fine Elements into Individuation, Individuation into Reason, and Reason or Mahān into Matter and-according to the Vedānta philosophy–Matter becomes merged into the fundamental Brahman. What period of time lapses between the creation of the universe and its destruction or merging in nowhere mentioned in the Sāṃkhya Kārikā. Yet, I think that the computation of time mentioned in the Manu-Saṃhitā (1.66–73), Bhagavadgītā (8.17), or the Mahābhārata (Śān. 231) must have been accepted by the Sāṃkhya philosophers Our Uttarāyaṇa, that is, the period when the Sun seams, to travel towards the North is the day of the gods, and our Dakṣiṇāyana, when the Sun seems to travel towards the South, is the night of the gods; because, there are statements not only in the Smṛtis, hut also in astronomical treatises that the gods live on the Meru Mountain, that is to say, on the north pole, (SūryaSiddhānta, 1.13; 12.35.67). Therefore, the period made up of the Uttarāyaṇa and the Dakṣiṇāyana, which is one year according to our calculations, is only one day and one night of the gods, and three hundred and sixty of our years are three hundred and sixty days and nights or one year of the gods. We have four yugas called, Kṛta, Tretā, Dvapara and Kali. The periods of the yugas are counted as four thousand years for the Kṛta, three thousand years for the Tretā, two thousand years for the Dvapara and one thousand years for the Kali. But one yuga does not start immediately after the close of the previous one, and there are intermediate years which are conjunctional. On either side of the Kṛta yuga, there are four hundred years; on either side of the. Tretā, three hundred; on either side of the Dvapara, two hundred; and on either side of Kali there are one hundred. In all, these transitional periods of the four yugas amount to two thousand years. Adding these two thousand years to the ten thousand years over which the Kṛta, Tretā, Dvāpara and Kali yugas extend, we get twelve thousand years. Now, are these twelve thousand years of human beings or of the gods? If these are considered to be human years, then, as more than five thousand years have elapsed since the commencement of the Kali yuga, not only is the Kali yuga of a thousand human years over, but the following Kṛta yuga is also over, and we must believe that we are now in the Tretā yuga. In order to get over- this difficulty, it has been stated in the Purāṇas that theses twelve thousand years are of the gods. Twelve thousand years of the gods mean 360 x 12000 = 43,20,000, that is, fortythree lakhs and twenty thousand years. The fixing of the yuga in our present almanacs is based on that method of calculation. This period of twelve thousand years of the gods, is one mahāyuga of human beings, or one cycle of four yuga of the gods. Seventy-one such cycles of yugas of the gods make up one 'manvantara', and there are fourteen such manvantaras. But, at the commencement and the end of the first manvantara and subsequently at the end of each manvantara, there is a conjunctional period equal to one Kṛta yuga, that is to say, there are fifteen such conjunctional periods. These fifteen conjunctional periods and fourteen manvantaras make up one thousand yugas of the gods or one day of Brahmadeva (Sūrya-Siddhānta 1. 15–20); and one thousand more such yugas make up one night of Brahmadeva, as has been stated in the Manu-Smṛti and in the Mahābhārata (Manu-Smṛti 1.69–75 and 79; Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 231. 18–31 and the Nirukta by Yāska 14.9).

According to this calculation, one day of Brahmadeva amounts to four hundred and thirty-two crores of human years, that is to say, 4,320,000,000 years. And this is called a 'kalpa'[6],

When, this day of Brahmadeva or kalpa starts:-

avyaktād vyaktayaḥ sarvāḥ prabhavanty aharāgame |

rātryāgame pralīyante tatraivāvyaktasaṃjñake ||

(Bhagavadgītā 8.18).

that is, "all the perceptible things in the universe begin to be created out of the Imperceptible; and when the night of Brahmadeva starts, the same perceptible things again begin to be merged in the Imperceptible", as has been stated in the Bhagavadgītā (Bhagavadgītā 8.18 and 9.7), as also in the Smṛti treatises, and elsewhere in the Mahābhārata. There are besides this, other descriptions of Cosmic Destruction (pralaya) in the Purāṇas. But as in those pralayas the entire universe, Including the Sun and the Moon, are not destroyed, they are not taken into account in the consideration of the creation and the destruction of the Cosmos. One kalpa means one day or one night of Brahmadeva and 360 such days and 360 such nights make up one of his years, and taking the life of Brahmadeva at one hundred such years, one half of his life is now over and the first day of the second half of his life, that is, of his fifty-first year, or the Śvetavārāha kalpa has now started; and there are statements in the Purāṇas that out of the fourteen manvantaras of this kalpa, six manvantaras are over, as also 27 mahāyugas out of the seventy-one mahāyugas of the seventh manvantara called Vaivasvata, and that the first caraṇa, or quarter of the 28th mahāyuga of the Vaivasvata manvantara is now going on (See Viṣṇu-Purāṇa 1.3). In the Śaka year 1821, exactly five thousand years of this Kaliyuga were over; and according to this calculation, there were in the Śaka year 1821, three lakhs and ninety-one thousand years still in hand for the pralaya in the Kaliyuga to take place; therefore, the consideration of the Mahāpralaya to take place at the end of the present kalpa is a far, far, distant thing. The day of Brahmadeva, made up of four hundred and thirty-two crores of human years, is now going on and not even the noon of that day, that is to say, seven manvantaras are yet over.

As the description which has been given above of the creation and the destruction of the Cosmos is consistent with Vedānta philosophy–and if you omit the Parabrahman, also consistent with Sāṃkhya philosophy–this tradition of the order of formation of the universe has been accepted as correct by our philosophers, and the same order has been mentioned in the Bhagavadgītā. As has been stated in the beginning of this chapter, we come across other ideas regarding the creation of the universe in some places in the Śrutis, the Smṛtis, and the Purāṇas, namely, that the Brahmadeva or Hiranyagarbha first came into existence, or that water first came into existence and a Golden Egg was born in that water from the seed of the Parameśvara etc. But all these ideas are looked upon as inferior or merely descriptive; and when there is any occasion to explain them, people say that Hiranyagarbha or Brahma-deva is the same as Matter. Even the Blessed Lord has in the Bhagavadgītā called this Matter of three constituents by the name 'Brahma' in the words "mama yonir mahad brahma" (Bhagavadgītā 14.3), and He has said that from this His seed, numerous beings are created out of Matter, as a result of three constituents. Vedānta treatises say that the description found in different places that Dakṣa and other seven mind-born sons, or the seven Manus, were born from. Brahmadeva, and that they thereafter created the moveable and immobile universe (Śriman Mahābhārata Ā. 65–67; Śriman Mahābhārata Śān. 207; Manu-Smṛti 1.34–63), which is once referred to also in the Gītā (Bhagavadgītā 10.6), can be made consistent with the above-mentioned scientific theory of the creation of the Cosmos, by interpreting Brahmadeva as meaning Matter; and the same argument is also applicable in other places. For instance, in the Śaiva or Pāśupata Darśana, Śiva is looked upon as the actual creator and five things, causes, products etc. are supposed to have come into existence from him; and in the Nārāyaṇīya or Bhāgavata religion, Vāsudeva is supposed to be the primary cause, and it is stated that Saṃkarṣaṇa (Jīva or Soul) was first born from Vasudeva, Pradyumna (Mind) from Saṃkarṣaṇa, and Aniruddha (Individuation) from Pradyumna. But as, according to the Vedānta philosophy, Jīva (Soul) is not something which comes into existence anew every time, but is a permanent or eternal part of a permanent or eternal Parameśvara, the above-mentioned doctrine of the Bhāgavata religion regarding the birth of Jīva has been refuted in the second portion of the second chapter of the Vedānta-Sūtras (Vedānta-Sūtras 2.2.42–45); and it is stated there that this doctrine is contrary to the Vedas, and, therefore, objectionable; and this proposition of the Vedānta-Sūtras has been repeated in the Gītā (Bhagavadgītā 13.4; 15. 7). In the same way, Sāṃkhya philosophers believe that there are two independent principles, Prakṛti and Puruṣa. But Vedānta philosophy does not accept this dualism, and says that both Prakṛti and Puruṣa are manifestations of one eternal and qualityless Absolute Self (Paramātman); and this doctrine has been accepted in the Bhagavadgītā (Bhagavadgītā 9. 10). But, this matter will be more fully dealt with in the next chapter. I have to state here only this, that although the Bhagavadgītā accepts the principle of the devotion to Vāsudeva and the theory of Action (pravṛtti) propounded in the Nārāyaṇīya or Bhāgavata religion, it does not accept the further doctrine of that religion, that Saṃkarṣaṇa (Jīva) was first created out of Vasudeva, and Pradyumna (Mind) out of Saṃkarṣaṇa, and

Aniruddha (Individuation) out of Pradyumna; and the words Saṃkarṣaṇa, Pradyumna, or Aniruddha are nowhere come across in the Gītā. This is the important difference between the Bhāgavata religion mentioned in the Pañcarātra, and the Bhāgavata religion mentioned in the Gītā. I have expressly mentioned this fact here in order that one should not draw the mistaken conclusion that the creed of devotional schools like the Bhāgavata school regarding the creation of the Cosmos or the Jīva-Parameśvara is acceptable to the Gītā, from the mere fact that the Bhāgavata religion has been mentioned in the Bhagavadgītā. Let us now consider whether or not there is some element or principle at the root of the perceptible and imperceptible or mutable and immutable universe, which is beyond the Prakṛti and Puruṣa mentioned in Sāṃkhya philosophy. This is what is known as Adhyātma (the philosophy of the Absolute Self) or Vedānta.

–-:o:–-

Footnotes and references:

[1]: