There’s No Place Like Here

by Ajahn Sumedho | 1999 | 1,740 words

Summary: There’s No Place Like Here

From Fearless Mountain Newsletter, Summer 1999, Vol 4 No 2

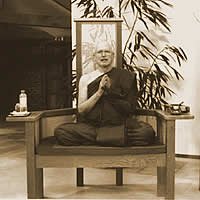

Ajahn Sumedho

December 24, 2004

Source 1: exoticindiaart.com

Source 2: abhayagiri.org

Read contents:

" . . . real wisdom can be detected only in very rare people"

" . . . real wisdom can be detected only in very rare people"

American born monk Ajahn Sumedho was ordained in Thailand 34 years ago. The senior Western disciple of the late Thai meditation master Ajahn Chah, he is abbot of Amaravati Buddhist Monastery near London, England, and spiritual leader of its many branches, including Abhayagiri Monastery in California. He was interviewed in May during a recent visit.

Fearless Mountain: What are some of your impressions of Abhayagiri Monastery, having spent a few days visiting?

Ajahn Sumedho: I"m very pleased with Abhayagiri. It has a good feeling. When I first visited a few years ago, it seemed very far away from the Buddhist group in San Francisco. But now everybody here feels it"s a good thing that there"s distance. In order to develop the atmosphere of a forest monastery, you don"t want to be right in the middle of the city or in a place that"s too convenient. Besides, here in the United States, most people have their own cars, so if people really want to come here, they can.

It"s impressive to see how many people are interested in the monastery—from the local area, to the San Francisco area, and even further. People come from Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington. That"s good. There"s an interest in Buddhism and in Buddhist monasticism.

FM: It"s certainly a perfect place for a forest monastery.

AS: Yes, it"s in a beautiful area, and there"s a lot of land. It has great potential. It"s also the kind of land that isn"t very suitable for purposes other than a forest monastery. You wouldn"t want to try to grow anything here.

FM: Although, this being Mendocino County, it"s rumored there used to be a marijuana farm here.

AS: Yes, well monks are forbidden to cultivate anything, marijuana included. [Laughter]

FM: Is there anything that"s particularly unique about Abhayagiri among the various monasteries in your wider monastic community?

AS: Before arriving here, Ajahn Pasanno had been Abbot of Wat Pah Nanachat for fifteen years. That"s special. Usually most new abbots have to learn on the job, but he"s already done that. He"s very experienced at monastic training and running a monastery. That"s rare. Both Ajahn Pasanno and Ajahn Amaro are well trained monks and seem dedicated and committed to staying here and developing Abhayagiri. California is quite lucky to have two such monks. They"re not all that common, and a lot of other places are begging for monks.

FM: You"ve spoken a lot about your experiences as a young monk in Thailand and how significant it was for you to be in a Buddhist country. What are your thoughts on how different it might be for somebody ordained here in California who may never spend any time as a monk in a Buddhist country?

AS: Well, I try to keep an open mind about it. I"ve seen too many people think that you can"t really live as a monk in the West, or that it"s better in Thailand. I have enormous gratitude and appreciation for my years in Thailand. I also recognize that in one"s practice, hanging onto views and opinions is the real problem, not the actual place or situation. The practice is about the mind. It"s about learning how to use what you have. It"s often difficult to see this. Because people can travel so easily, they don"t develop much contentment with the place they"re in. When they feel discontented, they can easily move on. This is a problem when Western people ordain. But from my own experience, I"ve realized that learning to be content and grateful for what I have is the essence of the holy life, not always looking for some better place. To get this across to people and for them to really appreciate it is another thing. Even though they can understand those sentiments, to actually feel them takes a real transformation of character, especially in a country where people have so many options and alternatives. So I"m simply encouraging the practice without holding up any place as being any better than any other place.

FM: I remember the story you tell in which, while still in Thailand, Ajahn Chah asked whether you"d return to America. When you said you didn"t think it would be possible to live as monk in America, he asked, "Why not. Aren"t there any kind people there?"

AS: Yes. To me, there seemed to be a real difference between living in an Asian country and a Western country. But the significance of his statement was to point out that wherever there are good hearted and generous people, I can go there. It"s not a matter of whether they are Buddhist or not. Having trained in Thailand, I was connecting my experience as a monk with a culture, with a people, with a situation. Because of that, I felt that my situation depended on these things. Eventually going to England, not really a country with a strong connection to Buddhism, I have had no problem in terms of support or respect. It"s given me a strong sense of the value of Buddhist monasticism as something that brings out the better qualities in humanity in terms of giving, looking after others, helping out, living in a contented way and so forth.

FM: You"re touching on some of the ways in which the monastic community can point out beneficial ways for laypeople to practice or provide a connection to the teachings.

We"ve developed the intellect—the ability to experiment, the wonders of modern science and so forth—but we"ve done it mostly out of curiosity and greed. If we had developed wisdom as well, then our intelligence would work in harmony with nature rather than by exploiting it.

AS: Because the monastic system is dependent on the lay community for requisites like food, we are connected in a very basic way. This draws out the generous qualities in people, simply to provide a meal or other requisites for the monastics. In affluent countries, the monastic lifestyle also provides an opportunity for people to reflect on what they really need in life. Doesn"t contentment come from the heart rather than from having everything you want? This sense of gratitude and contentment creates a mental state that"s very pure and conducive for seeing clearly. Our society is very restless, very critical, very aware of what"s wrong. We"re always thinking of ways to make things better than they are. So I think Buddhist monasticism is a good example for Americans to reflect on. Abhayagiri Monastery also provides an opportunity for people to make a short term or a life time commitment to monastic life in a country where monasticism has never played much of a role or exerted an important influence on the culture. And even if it doesn"t in the future, monasticism represents the goodness of humanity—letting go of things, being responsible for how you live, being kind, taking only what you need, and practicing in a way to free your mind from the causes of suffering. Just to have these operating in this country is a very hopeful sign, especially at a time when signs of gloom and doom are the dominant ones in the media. We can see the panic of the age. Fear of the future is coming from wondering what kind of monsters we"ve created and how they"re going to affect us. We"ve developed the intellect—the ability to experiment, the wonders of modern science and so forth—but we"ve done it mostly out of curiosity and greed. If we had developed wisdom as well, then our intelligence would work in harmony with nature rather than by exploiting it. But real wisdom can be detected only in very rare people. I think this is one reason why Western people are finding Buddhist meditation such a necessity in their lives. They realize it offers a way of training the mind and developing human potential in a way that our society has never before even thought of.

FM: Spirit Rock Center and the lay vipassana community are already veryAS1clip.jpg (7K) strong in this area. I"m wondering how you think the monastery can relate to this established lay community and what it will have to offer.

AS: I"ve been very impressed with Spirit Rock as a meditation center. Jack Kornfield first took me to look at the land before there was anything there, and I"ve seen it develop since then. It"s wonderful to see something come out of seemingly nothing. I find it very joyful to see what"s happening here in California and wish to encourage everybody to keep going. I"ve also seen what seem to be a real interest in and appreciation among the lay teachers for connecting to a tradition. Oftentimes, Buddhism is seen as just meditation techniques or the like. Really, though, there"s a whole tradition that has grown from the time of the Buddha up to the present. We are a part of something that reaches back to its founder in India two thousand five hundred forty two years ago. There"s a sense of belonging and continuity, that this isn"t just some kind of new age movement or fashion of the moment. It"s something that has proved itself as being of benefit through rising and falling kingdoms, empires, and civilizations. The remarkable thing with the Buddha- dhamma is that it"s still very pure. The teaching has never been corrupted or really damaged. It"s based on a truth that is still valid for this time. It"s not an antiquity. It"s not interesting because of its age, but because of its wisdom.

Comments: