The Dawn of the Dhamma

Illuminations from the Buddha’s First Discourse

by Sucitto Bhikkhu | 76,370 words

Dedication: May all beings live happily, free from fear, and may all share in the blessings springing from the good that has been done....

Chapter 25 - The One Who Knows

Athakho bhagava udanam … anna kondannotveva namam ahositi.

Athakho bhagava udanam … anna kondannotveva namam ahositi.

Then the Blessed One uttered the great exclamation: “Truly, it is the good Kondanna

who has understood, it is the good Kondanna who has understood.”

Thus it was that the name of Venerable Kondanna became: Anna Kondanna—

“Kondanna who understands.”

These are the concluding words of the Sutta. They remind us once again, after this long account, of the response to the turning of the Dhamma Wheel—the central significance of the teaching. The Buddha himself makes no comment on the delight of the devas or the effect of the teaching. He simply relishes the significance of that insight, “whatever has the nature to arise, all that has the nature to cease.” When one person attains Right View, it means more in terms of transmission of the Dhamma than any other response, regardless how jubilant, where insight is lacking. Jubilation, after all, arises and passes away and the world in general remains none the wiser for it—as anyone who has witnessed the finals of a sporting event can testify.

This great utterance of the Buddha about Kondanna"s understanding is not meant to celebrate his teaching of the abstract doctrinal aspects of Dhamma but that of the Dhamma becoming a living experience through Right Understanding. Kondanna heard the Buddha"s words and his insight was a realization of the causal nature of existence. This is a true transmission, a personal realization expressed in his own terms, rather than a mimicking of the Teacher. No wonder the Buddha expresses his approval! And he does so with that difficult to translate word “bho,” a term of address implying both friendship and respect. The first disciple has arisen. A way to the Truth which the Buddha felt would be difficult for people to understand has been communicated. There is hope for this world.

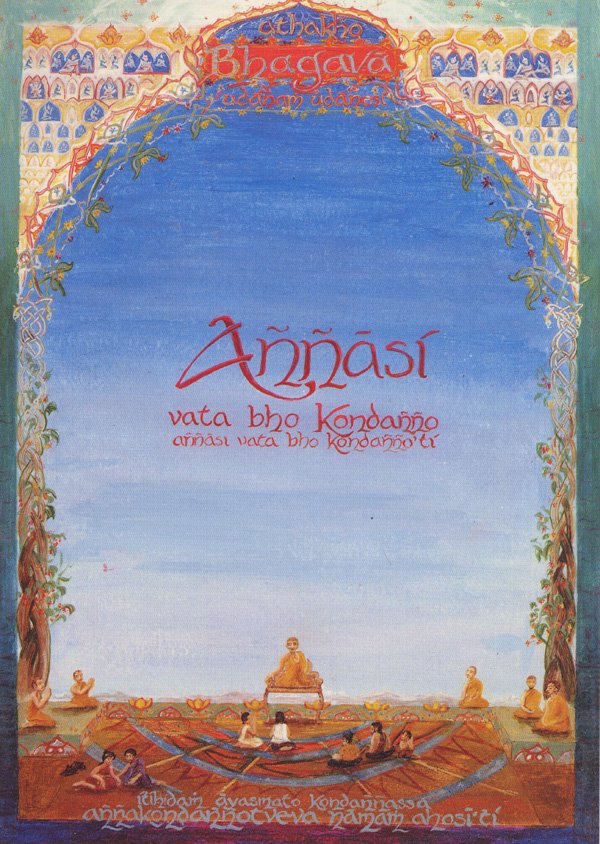

In this painting, I use the word “Annasi”—“he has understood”—as the central feature with the serene and all embracing sky as the background. Understanding is the subject, rather than Kondanna. More central to the theme than Kondanna as an identity is the non personal quality of awareness. This quality of knowing, of insightful awareness, does not arise and pass away even though the mind consciousness that connects or looks into that state of knowing can be very impermanent. For most people, such moments of profound insight are very brief and rare at first. But they are never really forgotten, and there is the possibility of remembering. It becomes possible to let go, own up to timeless Truth and allow the mind consciousness to relax and move towards a more serene, timeless reflection. That which knows causality and the limitation of all causal conditions is not itself caused. So sometimes it is called the Uncaused, or the Unconditioned, or the Unborn. Because it does not arise, it does not pass away, so we also call it the Deathless.

Some people like to personalize that which knows and call it “The One Who Knows” or “Buddha nature” or they give it a function such as “the Knowing.” Of course, these are all terms, ideas that act as pointers but they too just arise and pass away. The cultivator of Dhamma contemplates this “Knowing” and sees that it does not belong to anyone—it has no personal characteristics, it is not bound or located in time or space. Hence arises the insight known as anatta, not self (or non self)—the complete freedom of the mind from any need to hold, identify or attain. Truth is no one"s servant or possession, nor is it limited. It is like the sky of this painting. The sky above India in 500 B.C. may have been bluer and cleaner than that above the twentieth century industrialized world, but its all embracing quality has not changed. So Truth is void of all characteristics apart from boundlessness and the ability to contain all manner of phenomena. Here, it is painted blue—the color of peace and infinity, the coolest receding color. The focus of the painting is that sky—that all embracing peace and infinity. It is accessible to all; that is the real encouragement. From our own insight, perhaps expressed in different words, we can all recognize Truth.

Truth, however, requires expression in ways that are not ultimate because language is not an ultimate reality. Language deals with appearances. Even the language of our own thoughts is based upon perceptions which we have seen are not ultimate truths. They mirror conventional reality. So when it comes down to the teaching and encapsulation of the Dhamma, conventional expressions are necessary because the Dhamma has to be realized by people living in the conventional world. There are many different means of describing the Path and the goal, and encouraging the interest and right attitudes that will be conducive to practice. These painting"s are of those means.

I use the elaborate arch that frames the sky to depict the conventions of the world. Conventional teachings can be elaborate or simple, beautiful or functional—it"s a matter of taste. But there are plenty of them. Each teacher may add one or two more to the general stockpile. Some conventions get outdated or lose their appeal but for the most part they all have a beauty and a value, and when used skillfully, they encourage the realization of Ultimate Truth. In fact, most people would never realize Ultimate Truth without them. The Buddha left the teachings of Dhamma (which include the Four Noble Truths) and the Vinaya. These form the arch that improves our view of the Unconditioned sky and helps us to see it clearly. But if we get fascinated by the conventions, we miss the point too!

Another feature at the bottom of the painting is the bhikkhu giving a Dhamma talk. This could be Kondanna, or some other monk, giving a sermon to a few fellow monks and some lay people. It"s true, Kondanna had insight but he was not mentioned as a great teacher. It is said that he spent most of his time practicing on his own, returning after twelve years to pay his respects to the Buddha. He did not become a chief disciple like Sariputta and Moggallana, nor a great teacher like Kaccayana, nor a bastion of the Sangha like Maha Kassapa, Upali and Ananda. Yet he did realize the Deathless.

Teaching Dhamma is not easy for everyone—some enlightened beings have no gift for words while some great speakers are far from enlightenment. Here, the speaker is meeting a rather unreceptive audience. One of the monks seems to be following what is being said. The others appear bored or even displeased. Similarly with the families below, only one couple seem to be interested. As for the rest of them, they"re thinking, “Everything that arises passes away? So what!” The floor tells us why this message isn"t well received. The place where we are, where we walk, sit, live and die, is a place of strong movement this way and that. It is impermanent, true, but the movement whirls us away from the quiet reflection of wisdom. How many of the people in the painting are really listening? Does anyone notice the sky that looms behind?

Teaching Dhamma is not easy for everyone—some enlightened beings have no gift for words while some great speakers are far from enlightenment. Here, the speaker is meeting a rather unreceptive audience. One of the monks seems to be following what is being said. The others appear bored or even displeased. Similarly with the families below, only one couple seem to be interested. As for the rest of them, they"re thinking, “Everything that arises passes away? So what!” The floor tells us why this message isn"t well received. The place where we are, where we walk, sit, live and die, is a place of strong movement this way and that. It is impermanent, true, but the movement whirls us away from the quiet reflection of wisdom. How many of the people in the painting are really listening? Does anyone notice the sky that looms behind?

Other teachers fare better. Some have a tool kit filled with skillful means such as clever arguments, meditation techniques or personal charisma which capture people"s attention. Some great teachers have everything going for them; so do some great frauds. When one uses skillful means, and they are successful, it does not really matter who the teacher is. For this reason, much of Buddhist practice is described and conveyed in terms of skillful means. Techniques, practices or conventions are used as access points to the Dhamma. Skillful means are established but not each one is suitable for every personal taste. In order to survive through time, abstract concepts are needed. Myth, symbols, archetypes and even temples and shrines or living beings are commonly used vehicles by which conceptual and abstract terms can be conveyed. Within Buddhism, there is a rich storehouse of skillful means as well as abstract concepts. It is so rich and varied, people actually quarrel over which is the right one! This is why the presence of a living teacher is invaluable to help us assess the suitability of skillful means or to properly interpret the language of the teaching. Such a person should be one who is well trusted and who has contemplated the teachings in the light of his or her own experience. If this teaching can be communicated so that it is understood by just one person, then it can survive. The living, breathing individual experience of the Dhamma is an indispensable aspect of the teaching. It brings the teaching to a life that goes beyond the end of the discourse. Hence, the Buddha rejoices.