The Dawn of the Dhamma

Illuminations from the Buddha’s First Discourse

by Sucitto Bhikkhu | 76,370 words

Dedication: May all beings live happily, free from fear, and may all share in the blessings springing from the good that has been done....

Chapter 9 - Light On Dukkha

Idam dukkham … cakkhum udapadi nanam udapadi panna udapadi vijja udapadi aloko udapadi.

Idam dukkham … cakkhum udapadi nanam udapadi panna udapadi vijja udapadi aloko udapadi.

There is this Noble Truth of Suffering: …

This Noble Truth must be penetrated to by fully understanding Suffering: …

This Noble Truth has been penetrated to by fully understanding Suffering:

such was the vision, insight, wisdom, knowing and light that arose in me

about things not heard before.

With these words, the Buddha goes on to deepen the significance of what he has just outlined. The repeated phrases of this section point to a penetration of the meaning of the Truths. In some ways, nothing new is declared, but here the Truths are gone through in twelve stages, three to each Truth. In each case, the first stage is a fuller reflection on the import of bearing the meaning of the Truth in mind; the second stage demonstrates the way of practicing with that Truth; the third fully penetrates the significance of that Truth. Together, the twelve stages define the practice.

The most striking feature of this section (particularly evident when chanted) is that there seems to be similar results both from each successive level of understanding as well as from applying oneself to each of the twelve aspects of the Four Noble Truths. The understanding that there is suffering or that suffering has been abandoned are described alike as “vision, insight, wisdom, knowing and light” (or “enlightenment”). Together, these present the Truths and “Awakening” in an interesting way: could it be that the mind that can see dukkha is operating in the same liberated mode as the mind that sees the cessation of dukkha? Since it appears to be so, how are we to define Awakening?

Could it be that we don"t progressively “become” Awake? In a sense, we already “are” Awake, but our wrong ways of interpreting things keep blurring the picture. There is only one thing that all twelve stages have in common, apart from being symptomatic of enlightenment—they all present a highly subjective experience without mention of self. They are all expressed as: “There is; it is to be; it has been.” The unenlightened perspective surely is: “I am; I should; I have…” If I was a mathematician, I could probably draw up an equation based upon these data which concludes: “I am” = “unenlightenment.”

The description of the practice of the Four Noble Truths does not suggest a process of becoming enlightened. It seems that a particular viewpoint is sustained, and understanding arises through it. The viewpoint is a focus upon dukkha in an objective, dispassionate way. This affects intention—the mind inclines towards understanding Truth rather than experiencing calm, stimulation or happiness. The way the mind works is that intention guides and sustains the quality of attention. So when the intention is to penetrate the experience of dukkha, attention gathers onto that feeling and investigates it. This leads to a most powerful insight because it reveals that dukkha is structured, created and not absolute, and therefore possible to be dismantled or not created.

In brief, the sequence as it appears—because words have to appear sequentially—does not indicate a progressive quality in terms of awareness but of the way that awareness sweeps through the experience of dukkha and fully maps out the predicament of the five aggregates. In speaking of the Way, the Buddha said it was one of deepening realization, but the essence of that realization is not delayed in time.

Whoever sees suffering, sees also the arising of suffering, the cessation of suffering, and the Path leading to the cessation of suffering.

(Samyutta Nikaya: [V], Truths, III, 10)

A common recollection of the Dhamma chanted in monasteries every day is of the teaching being likened to a lamp or the sun illuminating the world. The extension of practice is one of bringing that light to bear on all aspects of the khandhas. Then the Path is one of bringing consciousness into accord with Ultimate Truth.

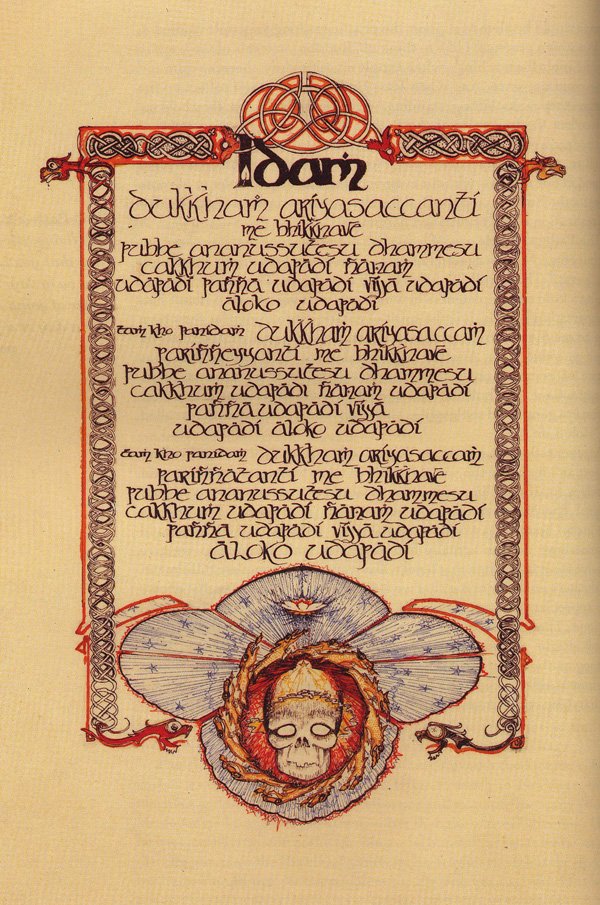

The sequence of illustrations that cover this fourfold exposition on practice uses repeated motifs. At the top center is the symbol of the self. It is an interweave of lines that appear to create a solid form, but which is mostly empty space woven by one line that manifests as two creatures. These two signify un knowing and desire. This subject undergoes transformation in how it appears throughout the sequence. It is not eliminated but turned into a source of radiance by the practice of Dhamma. The bottom center image is a reflection or further comment upon the top center image. In this first picture, we have the human paradox—the physical scenario of mortality played out against a backdrop of something more boundless, radiant and pure. We intuit a possible Deathless, immortal or liberated state. In a way, all our desires are sublimations of the yearning for freedom. The picture on the bottom suggests that the circling twelve headed fiery Wheel of Dependent Arising is getting in the way. But notice, there is a light rising behind that skull. And someone with sharp eyes can see that the very form of fiery heads proceeding in a clockwise direction intrinsically creates a twelve headed form of the radiant blue backdrop interconnecting with the clockwise circle. Going anti clockwise, and purely because there is a Dependent Arising, is the Dependent Ceasing: “With the cessation of ignorance is the cessation of "sankhara" … the cessation of dukkha.”

However, the general mood of this illustration is one of being bound up. That is what the intertwining of the borders suggests. Liberation seems a long way from the experience of dukkha. We don"t feel very inspired or liberated by the statement “there is suffering”; after all, what is enlightening about that?

The clue to liberation is hinted at in the expression used. The formulation of the words is slightly unusual: it"s not the way that the average person would formulate the experience; they would probably say “I am suffering” or “She is suffering,” etc. In such a case, the unstated implication is that something has gone wrong for that person and we should do something to stop them suffering. The instinctive response to stop the suffering is firstly to see it all in personal terms, and secondly, to postulate non suffering and then to bring it about. So the movement is one of identification and desire.

However, based upon that appraisal, one might question if any such attempts can abolish dukkha in the way that the Buddha uses the word. With reflection, one may assume that, ultimately, we cannot get rid of “suffering;” that the best that can be effected are temporary alleviations of the problem through medicine, counseling, aid and amusement. This is the despair of existentialism. These methods of alleviation are so instinctive that even to question them brings up the response: “You mean, you can just coldheartedly sit back in a state of inertia and say, "There is suffering"; and that any attempt to do something about it is just unawakened desire!”

On the other hand, the approach of the Buddha"s teaching is based upon giving up the defenses, distractions or complaining that dukkha normally evokes in us; it feels like giving up the self that hides behind the defenses or goes elsewhere or does the complaining. To see if the method works, give it a test—not on the suffering that we can get rid of temporarily like discomfort or hunger—but on the dukkha that we can"t do anything about: for example, the dukkha of birth, aging and death (which we cannot control); then the dukkha of being separated from what we love and having to face what we dislike (a pattern which we can alter in detail but not in a fundamental way); and the dukkha of living as a separate individual in a world with which we must come to terms and which is bounded by the passage of time and the limitations of physical existence. Such subjects would be a worthwhile test; and in fact we have nothing to lose in not attempting to alleviate them.

What happens when we approach our fundamental predicament with close attention to the way it feels? As human beings, we have to get old and die. That feels like this. We feel frightened; and that is like this. When we reflect in this way, isn"t this conducive to a sense of stability and calm? Does this not give rise to a “knowing of the way it is” and hence, the possibility of relinquishing impossible expectations and notions of the way it “should” be? And when we have no notions of how things should be, doesn"t that make us clear and sensitive, more fully alive? In one who maintains clarity and openness, a strength of heart is available that we forget we have.

What becomes apparent is that the pain of death and grief is really the pain of not wanting it to be this way, not wanting to be experiencing these feelings. And the real internalization of the dukkha comes through trying to be separate from these feelings, trying to get rid of them. When we can accept separation and loss as a natural part of life, then the real soul destroying sense of alienation and “Why me?” does not arise. When we realize that we"re all subject to dukkha, then the pettiness, the jealousies and the grudges disappear. And we find, sometimes to our surprise, that we can cope with life"s changes. In the peace of not suffering and with the presence of knowing and clarity, there are new, real and relevant possibilities of what we can do. Instead of feeling hopeless and agitated in the presence of death, we can be with it in a loving and peaceful way.

The young have the dukkha of feeling they have to conform to the authority of those who are older, the dukkha of being restless, not having a good position, needing to prove themselves, having a lot of sense desire and being anxious about the future. The middle aged experience dukkha through the increased pressure of responsibilities, having a position to maintain, getting stuck in habits, losing some of their vigor and initiative and being anxious about the future. The elderly experience dukkha through not being able to keep up, loss of position and role in society, feeling unwanted, dimming of the sense faculties and being anxious about the future. Then there"s always the regret over past actions, the limitations of body and mind and the sense of needing to find some meaning in life. So there is dukkha; but isn"t it a relief to know that it"s not my fault?

I recall people hearing these teachings in monasteries and Dhamma centers and meeting others who had come to the realization that “there is dukkha.” The response is generally: “So it"s not just "me" who feels like that!”—and sometimes even elation at having come out of the dull cocoon of confusion and self questioning: “Why me? Why did I get this bad deal?” Having birth traumas, being damaged as a child, being jilted, losing a job, being betrayed, getting sick, having your mother die, getting shortsighted, going grey, losing your husband, being manipulated by your boss, and the rest of it, is dukkha. But when these are seen as non personal—as aspects of a common experience—there is an opening of the heart to something more serene, less demanding and more compassionate. Our “own” stuff doesn"t seem so much then.

Isn"t it strange that sometimes the greatest sense of solace is to know that you"re not alone, and that you won"t be ostracized? So it"s not that there isn"t any dukkha, but now we know the pitch, and our heart feels free from that; what has changed is the perspective—a perspective that we call Right View, the view that is not self. As has been described, Right View is the basis for Right Intention and Right Action; so it doesn"t mean that we won"t try to change or improve our experiences and circumstances, but that our actions will not be compulsive, bitter or arrogant. Consider the actions of exploitation and even wanton destruction of life that come about through the wish to make things better—for “me” and “mine.”

To know “there is dukkha” is a radical step. The common myth that is perpetuated in society is that the normal person is happy, balanced and integrated—otherwise there is something wrong; maybe they"re mentally unstable. We"re even alarmed by unhappy people. Everyone in the media is smiling and cheerful; the politicians are all smiling, cheerful, confident; they even make corpses up to look smiling, cheerful and confident. The problem arises when you don"t feel cheerful and confident, when you can"t live up to one of the images of the model person. This happens when you don"t have the right appearance or status symbols, your performance doesn"t make it and you"re out of touch with the latest trends; or maybe you are just poor, someone that the society doesn"t want to acknowledge. Unhappiness, then is a sign of failure. Others think, “They"re not happy, maybe they didn"t do enough. And maybe they"ll want something from me; so better steer away from them.”

But “there is dukkha” brings us all together. The rich suffer from the fear of losing their wealth and security, and the mistrust of others—or even the guilt of being more affluent. The poor suffer from material need and the degradation of being treated as second rate; and the suffering is compounded when those positions are taken as personal identities. It"s the difference between “an enslaved person” and “a slave.” As long as those circumstances are taken to be identities, we adopt the degradation or bitterness, or the conceit and paranoia that each entails. Then the dukkha of circumstance becomes a permanent feature of the heart and mind and affects our attitudes and actions. Is a poor person, for example, someone who has little money; or is it someone who does not have a good proportion of what the society"s model for a happy human being has? Isn"t their experience of suffering compounded out of being rejected, and therefore feeling inadequate, bitter and depressed?

On a recent pilgrimage in India, I met many people with very little cash and only a few old clothes; but they were not carrying poverty around as an identity, so they weren"t suffering from it. I met a Sikh temple attendant who lived in one room with his wife and four children. His only furnishings comprised a bed, a stove and a cupboard. They were not embittered or depressed; far from it. They were in touch with something more reliable than material good fortune. There was the dukkha of lack, and yet not of suffering. That"s the way it is; the social model (at the village level at least) is not the person who is happy because of what they own, but who lives according to principles of dhamma.

When people live in accordance with Dhamma, then the limitations, the needs and the lacks, are acknowledged and effort is put into obtaining the necessities of life through what material comforts are available. In cases of real deprivation, surely a major contributor is the greed and exploitation of others; and that comes from the identification with material excellence. If we could all accept the experience of limitation on our resources and comforts, if our standard of living were not so high, there would be less people who felt “poor.” Maybe with more sharing, there would be less severe physical deprivation. Instead of having a golf course in desert regions, refrigeration, air conditioning and 48 T.V. channels, we could try to accept the limitations that acknowledge “there is suffering.”

It"s not just a matter of everyone feeling wretched, but of learning to know and accept that this realm is one of limitation; to wake up to how it is; and where the real problem is—dukkha puts us in touch with the heart of what motivates our lives. The practice is one of sharpening the attention to catch our instinctive reactions of blaming ourselves, blaming our parents or blaming society. In this way, there is a focus on that recurring mood and the knowing of it as a mood; not to deny it, but to know it as it is. Then there is the realization of that which is not suffering, that which is knowing and insightful. This way of insight can help us to cope with dukkha even on a small scale in daily life situations such as when we feel bored or ill at ease; so instead of trying to avoid these feelings by buying another fancy gadget, we can look into the heart and develop a gentle and nourishing response to any sense of inadequacy.

Hence dukkha is to be understood, looked at and investigated in order to find its roots in the heart, and what connects our conscious motivation to the Awakened mind. Rather than denying that there is any dukkha: “Life"s great! I"m going to Hawaii, and I"m going to have a good time!”, we recognize that the constant need to be entertained, to progress or to be appreciated by someone is a sign of not being fully at ease with ourselves. Again, the instincts leap to the defense: “What"s wrong with going to Hawaii, getting ahead in life, or having a loving relationship?” In itself, nothing. Where the dukkha is depends upon what has motivated those impulses and we can only know that for ourselves. Relationships tend to go wrong when we need something from the other person; they seem to work when we support one another. The most productive activities are the ones that ask us to develop in ourselves. Knowing this, we can use the dukkha, the inevitable misunderstandings and inadequacies, to develop new perspectives or, at least, tolerance in ourselves.

If inadequacy is taken as a personal attribute, the dukkha is driven deeper and life can be lived in a very wretched or distracted way. Through dukkha not having been understood, there"s a kind of despair about the human predicament—when will we ever get rid of the social injustices and the violence and the unfairness? Why is it that the law and order campaign is a failure; that the civil rights movement is not working; that emancipation and independence do not necessarily bring about contentment and opportunity; that Communism was a failure; that the American Dream went wrong; that better pay and better working conditions have not produced the Utopia? Because we haven"t understood dukkha, that"s why. None of these ideas is wrong, and they have not been without some good effects, but they don"t rule out self view. As long as that view is maintained, the system is always going to be used for selfish aims—by some, at least—or for noble intentions by others, but based upon personal perspectives of what is thought to be good for someone else.

To have understood dukkha is to have known that taking the five aggregates as a personal identity is the problem. Thus, understanding comes about through one"s own dispassionate awareness to bear upon how, where and when it hurts. When one takes the five aggregates as a personal identity, it follows that there is the desire to be someone; hence the identification with race, nationality and sex, and all the desires and prejudices that accompany these. Subsequently we identify with those desires and perceptions; and we believe that that"s what we are. So we expect our bodies, mental and physical feelings and perceptions of ourselves to be contented. Waking up means we accept that it can"t be that way. Then we can stop suffering over it and sift our attention and intention beyond self view. That is the essence of liberation. It is just one point. To have understood the point thoroughly means that this seeming imponderable mass of human confusion and pain has a source that can be abandoned.