The Dawn of the Dhamma

Illuminations from the Buddha’s First Discourse

by Sucitto Bhikkhu | 76,370 words

Dedication: May all beings live happily, free from fear, and may all share in the blessings springing from the good that has been done....

Introduction

The Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta is the first sermon of the Buddha. In the Theravada recension of the Buddha"s teaching, presented in the ancient Pali language of India, there are three main divisions: the Discourses (Sutta Pitaka), the Books of the Discipline (Vinaya Pitaka) and the Books of Metaphysics (Abhidhamma Pitaka). The Sutta appears twice in this body of work known as the Pali Canon: namely in the Vinaya Pitaka (Mahavagga: [I], 6, 17-31) and in the Sutta Pitaka (Samyutta Nikaya: [V], Truths; II, 1).

Scholars generally agree that the material in these works was collected over a period of time which extended beyond the Buddha"s passing away (Parinibbana). It is traditionally held that the main body of the Sutta Pitaka was recited by the Venerable Ananda at a Sangha Council held soon after the Parinibbana, and, at that same meeting, the Venerable Upali recited the texts of the Vinaya. Even though these are enormous texts, it is not impossible for clear minded beings to remember them and learn them by heart—in fact, there are a few bhikkhus in this present day and age who can do just that. However, it is generally agreed that these early recitations were later polished and augmented into the texts that we have today. In fact, some of the suttas are set in a time that postdates the Buddha"s life, while chapters of the Vinaya relate the affairs of the First and Second Sangha Councils (held about 100 years apart). So, subsequent additions and commentaries are an accepted part of the Canon. It is generally agreed that the text of the Abhidhamma is of a later date than that of the other two Pitakas; which does not mean that the ideas expressed in the Abhidhamma are necessarily of a later date—only that its casting into a fixed form is.

As these texts became established, a high degree of uniformity and agreement prevailed. The Sangha was obviously most concerned to preserve the teaching of the Buddha, and if groups of monks learned and recited sections of it by heart, any spurious additions would immediately be noticed by others who had learned that text. Much the same practice prevails today with the monks" regular recitation of the Patimokkha (the Monastic Rule). Since it is always recited in a group, mistakes become quite apparent. With this method of preserving the teachings, any subsequent additions would only be made with the consent of a council of elders.

The process of oral transmission affects the style of the text—formulae and stock passages abound. These may be irritating to a modern reader, but are helpful to a reciter and supportive to a listener. Rather like a mantra, or an often repeated story, familiar phrases have a calming effect. They establish certain themes in the memory of the listener, change the mental mode from discursive rational processes to those of reflection, and create a feeling of belonging. Thereby the listener, the reciter and the text itself come together. The listener and the reciter are taken into the timelessness of a tradition. This is an experience that lifts us out of the particular concerns of the day or of our personal identity. Chanting itself, done in a monotone, has a tranquilizing effect on the mind, whatever the content, both for those who listen and those who chant. The reciters have to learn, when chanting in a group, to enunciate simultaneously and at the same rhythm and pitch; this requires the attention that is supportive of contemplation.

After a few hundred years, the material of the Pali Canon was written down. This occurred at the beginning of the Christian Era in what is now Sri Lanka. After that, no further addition to the Canon took place. There are several extant manuscripts, which differ slightly, owing to copyists" errors and the ravages of time. The first text using the Roman alphabet was composed in Thailand under the direction of King Chulalongkorn in the latter years of the 19th century. Somewhat after that, the Pali Text Society was founded in Britain by T.W. Rhys Davids. This Society has taken upon itself the task of producing a Roman alphabet edition of the Pali texts as well as a translation into English. The text that I have used as a basis for the illuminations is actually the version written in the Royal Thai Chanting Book, and is chanted by contemporary Thai bhikkhus. It differs from the Pali Text Society edition on a few minor points.

The accepted status of the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta as the first of the Buddha"s discourses gives it a particular appeal. It also elucidates the Four Noble Truths, the teaching that he calls “particular to Buddhas,” and which is considered to be the heart of his dispensation. Nowadays the Sutta is especially chanted on Asalha Puja which, in the Buddhist calendar, usually falls on the full moon day of July. This is traditionally held to be the day when the Sutta was first taught by the Buddha, and it also immediately precedes the beginning of the three month monastic Rains Retreat (Vassa).

In Thailand today, many men will take ordination as Buddhist monks for the period of the Vassa. The Vassa is recognized as a time for more detailed and thorough practice when the bhikkhus refrain from traveling, and determine to abide together in their monasteries. This gives the teacher an excellent chance to supervise his disciples, as well as allowing the Sangha the opportunity to clarify the observances and principles of training together. So for many monks, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta signifies a time when they can attend to their meditation practice and training with vigor and in a supportive environment of stability and instruction.

Part of that practice may well be to learn the recitation of several suttas, including the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, both for their own reflection and to support the practice of the laity, who will congregate at such recitations. A group recitation followed by a period of meditation and a desana (talk on Dhamma) on the theme of the Sutta would form an intrinsic part of the monks" and laity"s observance of Asalha Puja. Because this happens every year throughout the Buddhist world, the occasion has a value that extends beyond the meaning of the Sutta itself. It establishes a community in the Dhamma, and a sense of kinship with Buddhists near and far, from bygone ages up to the present.

All of these considerations may help to explain the approach that I have taken in this current work. My intention is not to present a scholarly exegesis of the meaning of the Sutta; such interpretations as I offer should be understood as reflections from my own practice of the Dhamma rather than absolute statements about the meaning of the words. However, I have tried to consult the extensive compilations of the suttas and to follow a pattern of reviewing the Sutta phrase by phrase, if not always word by word.

Some Notes on the Text

The quotations of translations from the Pali scriptures are from various sources, all of which I would recommend reading. The comprehensive edition is that presented by the Pali Text Society, which has been working on authoritative editions of the texts in Pali, with translations into English, for most of this century. Some of the earlier translations have aged a little, especially when seen in the fuller light of understanding of the nature of the teachings and the practice. There is a recent translation of the Digha Nikaya (The Long Discourses) by Maurice Walshe, entitled “Thus Have I Heard,” and published by Wisdom Publications. Wisdom are also currently in the process of publishing a new translation of the Majjhima Nikaya (Middle Length Discourses) by Venerable Nanamoli Thera. Ven. Nanamoli also made some other fine translations of Suttas and produced a book called “The Life of the Buddha” (published by the Buddhist Publication Society), which is made up, for the most part, of extracts of suttas compiled into a narrative framework. Its excellence is not only in the quality of translation, but in the breadth and interest of the numerous extracts, which avoid the repetition of the complete texts. The Buddhist Publication Society produces many good books, commentaries on suttas and writings of contemporary Buddhists at very low cost.

I have quoted from the Pali scriptures many times in the course of this book. Generally I have used the Pali Text Society translation, or Ven. Nanamoli"s; occasionally I have used a translation of my own. Quotations from the Sutta Nipata are generally from the translations of Ven. Dr. H. Saddhatissa, published by Curzon Press. I have retained the Pali titles for the Nikayas to avoid the confusion of differing English translations. Digha Nikaya, for example, is literally “The Collection of Long (Suttas),” although the PTS translation is titled “Dialogues of the Buddha” and Maurice Walshe"s is titled “Thus Have I Heard.” Majjhima Nikaya has up to now been known as “Middle Length Sayings,” and Anguttara Nikaya as “Gradual Sayings.” What new translators make of these titles is yet to be seen.

I have referred to the suttas of the Digha and Majjhima Nikaya by their Pali name and their number in the Nikaya: for example, Sabbasava Sutta is the second sutta in the Majjhima Nikaya. The Samyutta and Anguttara Nikayas have always had more complex references, owing to their construction—small suttas collected into chapters in books based on a particular theme within the Nikaya as a whole. In the Samyutta, the theme is a topic such as “Cause;” in the Anguttara, the theme is a number—“Nines,” for example, brings together suttas in which nine fold topics are referred to. In the case of these Nikayas, my reference begins with a Roman numeral in square brackets. This refers to the volume of the PTS English translation. The subsequent word refers to the “book” within that volume, and any other word to the chapter within that book. A subsequent Roman number refers to any other subsection, with the Arabic numeral referring to the number of the actual Sutta.

Use of Pali

I have used Pali in the commentary when that Pali word covers a range of meanings that the English can"t. If one tries to translate every word into English, one frequently has to use different English words in different contexts. The ideal solution is for the English language to take in these words as its own—as it has embraced “igloo” and “khaki” for example. When such incorporation seems possible, as in the familiar, almost untranslatable “dukkha,” I have used ordinary Roman type; otherwise, the Pali appears in italics.

“Kamma”—the Pali version of Sanskrit “karma”—is used not just to be consistent with the use of Pali throughout, but also to avoid confusion with the Vedic view of “karma.” The Vedic use, or at least the modern rendition of that term, signifies a process of cause and effect that pertains above and beyond the individual will. As such, it brings in notions of fate and destiny. The Buddha recognized that the kamma of the body, for example, was beyond our will—it is born, ages and dies according to bodily kamma. However, he stressed that the most significant kamma was the activity produced by intention, whose results are experienced by the mind. Because of the significance of intentional activity of body, speech or mind in the present, liberation is possible in this lifetime—we don"t have to exhaust the results of all past kamma.

Another problematic word is sankhara. Often, and most broadly, the word is translated as “condition,” which doesn"t immediately mean very much to a modern reader, although conditionality (and therefore, the Unconditioned) is the understanding of existence that is the foundation for the Buddha"s transcendence.

The Tathagata has taught the root of all that grows into existence; and he has explained what brings around its cessation. (Vinaya Mahavagga: [1])

A “condition” is something that affects the existence of something else: a necessary condition for fire may be wood, for example. Note that a condition is more than a cause: wood doesn"t cause fire. And one might add many other conditions that are necessary for fire: the intention to create a fire, the application of heat, the non appearance of water, etc.

The understanding of the Buddha was that what the ordinary person perceives as reality are conditions, and all conditions are ephemeral and impermanent (as the intention to create fire, the wood and the rest in the above example). Also, all conditions depend on other conditions: wood on trees, trees on earth, rain and air (and the non manifestation of herbivores), and so on. But where does it all begin? Where is the root condition of them all? Here the Buddha concerned himself only with the conditions of the human body and mind, most particularly with the mind. Hence sankhara, is often translated as “mental formations.”

One of the most significant conditions that arises through the activity of the mind is volition (or intention, or will). The mind not only receives impressions from the other senses, it determines what to attend to, what to ignore, and what to do with what it attends to. This determining is intention (cetana). Intention is the basis of kamma—actions that have a result which sustains a mode of personality. When thoughts are kamma productive, they stimulate activity and the results of the activity are acquired by the agent of the thought. If you think of stealing something and are moved by that thought, then what is immediately created is the impression of being the owner of that thought. One may then dismiss the thought (good kamma, kammically wholesome) or act upon it. If it is acted upon, this is bodily sankhara, and kammically unwholesome, which again sets up conditions of identity. By one"s actions, good or bad, is one known and defined; for one"s actions, one is responsible. Therefore kamma formations is another important condition of sankhara.

When thoughts and actions are not identified with, then they are called dhamma, meaning “things” in a more universal, impersonal way. An important Buddhist reflection is that “all sankhara are impermanent; all dhamma is not self.” The conditions that we identify with are of a transient nature; and things which we do not take as ours do not belong to some higher, other self either. Hence God—or the Universal Whole, or Ultimate Truth—is not a super person either, or an identity. It is the whole, not a fragment that can be defined into an identity separate from anything. The Buddhist reference to this whole is “the Dhamma,” a term also reserved for the presentation of Truth that we call the Buddha"s “teachings.”

The Background

“Buddha” means “The One Who Knows,” “The Awakened One.” It is, of course, a title that can be applied to a rare kind of human being—one who has realized Ultimate Truth through his own personal efforts (unlike “Arahants,” who realize enlightenment through following the teaching of a Buddha). The title Buddha is sometimes expanded to “Sammasambuddha,” meaning “completely self enlightened.” There are also Paccekabuddhas (Lone Buddhas), who have accomplished an enlightenment in like fashion, but who have no ability to teach others. The Buddha of this age spoke occasionally of Buddhas of past ages. They are listed as 28 in number in a way that is suggestive of mythical truth rather than historical record. There is also mention of a future Buddha, Metteyya (or Maitreya in Sanskrit), who will arise in the world of humans when the teachings of the Buddha Gotama have died out.

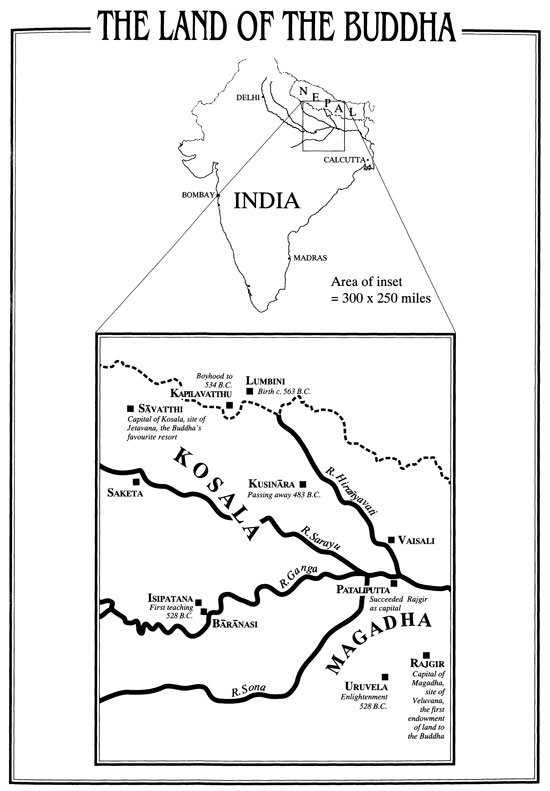

Before his enlightenment, the Buddha was known as Siddhattha Gotama, born the son and heir to Suddhodana, an elected chief of the Sakyan Republic. This republic, occupying a fragment of modern Nepal, was a vassal state of the larger kingdom of Kosala. Kosala occupied the northeast corner of modern Uttar Pradesh, and now includes Gorakhpur, Ayodhya and Varanasi. Throughout his adult life he gave ethical and contemplative teachings, acquired a considerable reputation and a number of followers, and passed away at a ripe old age, near the present town of Kasla in Uttar Pradesh. Nothing more definite than that is certain concerning the biography of the Buddha. Scholars even question the dates of his birth and death, mostly plumping for 563–483 B.C.

The Buddha regarded his teaching, rather than his past life, as the thing of importance; he only alluded occasionally to his life before enlightenment. Therefore, much of what passes for his biography has been pieced together from allusions in the scriptures and commentarial and apocryphal accounts—which were, no doubt, affected by devotees of later centuries trying to assemble a human image of the Master for devotional purposes. A notable modern effort, which also provides interesting descriptions of the Buddha"s country at that time, is “The Historical Buddha” (H.W. Schumann; trans. M.O"C. Walshe; Penguin London 1989).

By his own later accounts, Siddhattha, as a young man, reflected on the human lot of aging, sickness and death. The futility of living in a way that provided no means of dealing with these issues motivated him to leave home and wander as a religious ascetic (equivalent to a modern sadhu) at the age of 29. At that time, it was not unusual for older men to leave the family life when they were advanced in years and had fulfilled their family responsibilities. A strong family structure and inter dependency however, made it more unusual for younger men, and even rarer for women.

The Indian spiritual culture, into which Siddhattha was born, had two main branches: that of the brahmins, who were priests learned in the lore of the Vedas, and the only ones legitimately entitled to interpret the scriptures and perform rites and sacrifices to the Vedic gods on behalf of other folk; and samanas (literally “strivers”), who stepped outside of the brahmin framework, and were seeking religious truth by themselves in any number of heterodox ways. The Buddha frequently referred to his disciples as samanas, just as those who were not his disciples would refer to him in terms of no greater respect than “the samana Gotama.”

Among the samanas were the wanderers, called paribbajikas, apparently from brahmin caste. They had no particular doctrine in common, but were all independent seekers who might adopt a wide range of views and practices, staying with one teacher for a while and forming a group, then wandering off to another teacher and practice—rather in the fashion of modern spiritual seekers. The only commonly held ascetic practice seems to have been that of celibacy, while some would take up extreme forms of self mortification. In the suttas, there is mention of six famous teachers: Purana Kassapa, Makkhali Gosala, Ajita Kesakambali, Pakudha Kaccayana, Nigantha Nataputta (another name for Mahavira, the founder of the Jains) and Senjaya Belatthaputta. The teaching of Nigantha Nataputta prescribed a rigorous purification by asceticism and sense restraint, whereas the other teachings, though not fully presented, ascribe no importance to the actions of the individual in determining their future destiny.

Tradition has it that, after leaving his father"s home, Siddhattha spent six years as a wandering ascetic. He practiced for some time with Alara Kalama, a yogi who taught him how to attain the meditative absorption called the Sphere of Nothingness. Having mastered this, Siddhattha still felt dissatisfied, as it seemed to be a temporary evasion of the problems of life. He then sought out another teacher, Uddaka Ramaputta, who taught him a deeper absorption called the Sphere of Neither Perception nor Non Perception. Siddhattha also perfected this state but rejected it on the same grounds. During this time, perhaps periodically, the Buddha to be lived with a group of five fellow ascetics, who all looked to him as an example. They, however, lost faith in him when, after six years of extreme asceticism, he decided to abandon that path and adopt a more moderate (though by modern standards austere) style of practice. He wandered off on his own, and came at last to a place in the kingdom of Magadha called Uruvela—now known as Bodh Gaya. Here he practiced a form of meditation which was endowed with the reflective faculties of the mind, rather than being merely a temporary trance like transfiguration of consciousness. This led to the insights that undermined the foundations of the unawakened state. What was left was clarity, liberation and profound understanding of how the mind works.

The Buddha had realized that it was not going to be easy to convey his insights to others in a way that they could follow. By all accounts, he even doubted whether it was worth the effort—given the power that attachment has over people"s minds. Fortunately, compassion prevailed and he felt that there were those with “but little dust in their eyes” who would be able to see what he was pointing at. He considered locating his former teachers, but ascertained that they were both dead. Then he thought of his five former companions who were at that time some 130 miles away in the Deer Park near the ancient holy city of Varanasi (also called Baranasi). Accordingly, he set off on foot in that direction.

This was only seven weeks after his own unique enlightenment, so at that time he probably had not formulated a teaching. Certainly, his first dialog, with a naked ascetic called Upaka, whom he met on the way, bore no fruit. The Buddha coolly but confidently proclaimed to him his own realization in personal terms:

“Victorious over all, omniscient am I

Among all things undefiled,

Leaving all, through death of craving freed….”

To this, Upaka replied: “May it be so, friend,” and went off taking a different road.(Mahavagga: [I])

So the approach of giving a direct, personal testimonial to enlightenment was not well understood. Upaka responded with the equivalent of “So what?” The teaching was too subjective, and ultimately, it didn"t relate to the listener"s experience. The Buddha must have learned from that uninterested response; in the future, he rarely made proclamations about Ultimate Truth. Instead, he taught conventional truths which, if used skillfully, would lead to the experience of Ultimate Reality. The most constantly reiterated theme of this teaching is, of course, the exposition in terms of the Four Noble Truths.

When the Buddha arrived at the Deer Park, the Group of Five at first did not want to receive him. However, being moved by his radiant presence, they found themselves offering him a place to sit, although they still did not want to hear what he had to say. But the Buddha touched upon a theme that would have had immediate relevance to those seekers: “Give ear … the Deathless has been found; I instruct, I teach Dhamma. If you practice as I teach you, you will gain realization in terms of your own experience here and now. And you will come upon and abide in the supreme goal of the spiritual life….” Though they were still reluctant, they were impressed by the clarity and the confidence with which the Buddha spoke. So they listened and opened their hearts….