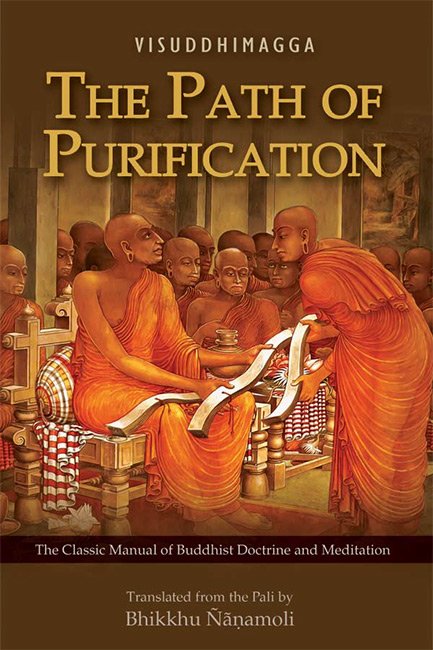

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes (1) The Kinds of Supernormal Power of the section The Supernormal Powers (iddhividha-niddesa) of Part 2 Concentration (Samādhi) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

(1) The Kinds of Supernormal Power

If a meditator wants to begin performing the transformation by supernormal power described as, “Having been one, he becomes many,” etc., he must achieve the eight attainments in each of the eight kasiṇas ending with the white kasiṇa. He must also have complete control of his mind in the following fourteen ways: [374] (i) in the order of the kasiṇa, (ii) in the reverse order of the kasiṇa, (iii) in the order and reverse order of the kasiṇa, (iv) in the order of the jhāna, (v) in the reverse order of the jhāna (vi) in the order and reverse order of the jhāna, (vii) skipping jhāna, (viii) skipping kasiṇa, (ix) skipping jhāna and kasiṇa, (x) transposition of factors, (xi) transposition of object, (xii) transposition of factors and object, (xiii) definition of factors, and (xiv) definition of object.

3. But what is “in the order of the kasiṇa” here? What is “definition of object”?

(i) Here a bhikkhu attains jhāna in the earth kasiṇa, after that in the water kasiṇa, and so progressing through the eight kasiṇas, doing so even a hundred times, even a thousand times, in each one. This is called in the order of the kasiṇas. (ii) Attaining them in like manner in reverse order, starting with the white kasiṇa, is called in the reverse order of the kasiṇas. (iii) Attaining them again and again in forward and reverse order, from the earth kasiṇa up to the white kasiṇa and from the white kasiṇa back to the earth kasiṇa, is called in the order and reverse order of the kasiṇas.

4. (iv) Attaining again and again from the first jhāna up to the base consistingof neither perception nor non-perception is called in the order of the jhānas. (v) Attaining again and again from the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception back to the first jhāna is called in the reverse order of the jhānas. (vi) Attaining in forward and reverse order, from the first jhāna up to the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception and from the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception back to the first jhāna, is called in the order and reverse order of the jhānas.

5. (vii) He skips alternate jhānas without skipping the kasiṇas in the followingway: having first attained the first jhāna in the earth kasiṇa, he attains the third jhāna in that same kasiṇa, and after that, having removed [the kasiṇa (X.6), he attains] the base consisting of boundless space, after that the base consisting of nothingness. This is called skipping jhānas. And that based on the water kasiṇa, etc., should be construed similarly. (viii) When he skips alternate kasiṇas without skipping jhānas in the following way: having attained the first jhāna in the earth kasiṇa, he again attains that same jhāna in the fire kasiṇa and then in the blue kasiṇa and then in the red kasiṇa, this is called skipping kasiṇas. (ix) When he skips both jhānas and kasiṇas in the following way: having attained the first jhāna in the earth kasiṇa, he next attains the third in the fire kasiṇa, next the base consisting of boundless space after removing the blue kasiṇa, next the base consisting of nothingness [arrived at] from the red kasiṇa, this is called skipping jhānas and kasiṇas.

6. (x) Attaining the first jhāna in the earth kasiṇa [375] and then attaining theothers in that same kasiṇa is called transposition of factors. (xi) Attaining the first jhāna in the earth kasiṇa and then that same jhāna in the water kasiṇa … in the white kasiṇa is called transposition of object. (xii) Transposition of object and factors together takes place in the following way: he attains the first jhāna in the earth kasiṇa, the second jhāna in the water kasiṇa, the third in the fire kasiṇa, the fourth in the air kasiṇa, the base consisting of boundless space by removing the blue kasiṇa, the base consisting of boundless consciousness [arrived at] from the yellow kasiṇa, the base consisting of nothingness from the red kasiṇa, and the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception from the white kasiṇa. This is called transposition of factors and object.

7. (xiii) The defining of only the jhāna factors by defining the first jhāna as fivefactored, the second as three-factored, the third as two-factored, and likewise the fourth, the base consisting of boundless space, … and the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception, is called definition of factors. (xiv) Likewise, the defining of only the object as “This is the earth kasiṇa,” “This is the water kasiṇa” … “This is the white kasiṇa,” is called definition of object. Some would also have “defining of factors and object”; but since that is not given in the commentaries it is certainly not a heading in the development.

8. It is not possible for a meditator to begin to accomplish transformation by supernormal powers unless he has previously completed his development by controlling his mind in these fourteen ways. Now, the kasiṇa preliminary work is difficult for a beginner and only one in a hundred or a thousand can do it. The arousing of the sign is difficult for one who has done the preliminary work and only one in a hundred or a thousand can do it. To extend the sign when it has arisen and to reach absorption is difficult and only one in a hundred or a thousand can do it. To tame one’s mind in the fourteen ways after reaching absorption is difficult and only one in a hundred or a thousand can do it. The transformation by supernormal power after training one’s mind in the fourteen ways is difficult and only one in a hundred or a thousand can do it. Rapid response after attaining transformation is difficult and only one in a hundred or a thousand can do it.

9. Like the Elder Rakkhita who, eight years after his full admission to the Order, was in the midst of thirty thousand bhikkhus possessing supernormal powers who had come to attend upon the sickness of the Elder Mahā-RohaṇaGutta at Therambatthala. [376] His feat is mentioned under the earth kasiṇa (IV.135). Seeing his feat, an elder said, “Friends, if Rakkhita had not been there, we should have been put to shame. [It could have been said], ‘They were unable to protect the royal nāga.’ So we ourselves ought to go about [with our abilities perfected], just as it is proper (for soldiers) to go about with weapons cleaned of stains.” The thirty thousand bhikkhus heeded the elder’s advice and achieved rapid response.

10. And helping another after acquiring rapidity in responding is difficult and only one in a hundred or a thousand can do it. Like the elder who gave protection against the rain of embers by creating earth in the sky, when the rain of embers was produced by Māra at the Giribhaṇḍavahana offering.[1]

11. It is only in Buddhas, Paccekabuddhas, chief disciples, etc., who have vast previous endeavour behind them, that this transformation by supernormal power and other such special qualities as the discriminations are brought to success simply with the attainment of Arahantship and without the progressive course of development of the kind just described.

12. So just as when a goldsmith wants to make some kind of ornament, he does so only after making the gold malleable and wieldy by smelting it, etc., and just as when a potter wants to make some kind of vessel, he does so only after making the clay well kneaded and malleable, a beginner too must likewise prepare for the kinds of supernormal powers by controlling his mind in these fourteen ways; and he must do so also by making his mind malleable and wieldy both by attaining under the headings of zeal, consciousness, energy, and inquiry,[2] and by mastery in adverting, and so on. But one who already has the required condition for it owing to practice in previous lives needs only prepare himself by acquiring mastery in the fourth jhāna in the kasiṇas.

13. Now, the Blessed One showed how the preparation should be done in saying, “When his concentrated mind,” and so on. Here is the explanation, which follows the text (see §2). Herein, he is a meditator who has attained the fourth jhāna. Thus signifies the order in which the fourth jhāna comes; having obtained the fourth jhāna in this order beginning with attaining the first jhāna, is what is meant. Concentrated: concentrated by means of the fourth jhāna. Mind: fine-material-sphere consciousness.

14. But as to the words “purified,” etc., it is purified by means of the state of mindfulness purified by equanimity. [377] It is bright precisely because it is purified; it is limpid (see A I 10), is what is meant. It is unblemished since the blemishes consisting of greed, etc., are eliminated by the removal of their conditions consisting of bliss, and the rest. It is rid of defilement precisely because it is unblemished; for it is by the blemish that the consciousness becomes defiled. It has become malleable because it is well developed; it suffers mastery, is what is meant, for consciousness that suffers mastery is called “malleable.” It is wieldy (kammanīya) precisely because it is malleable; it suffers being worked (kammakkhama), is fit to be worked (kammayogga), is what is meant.

15. For a malleable consciousness is wieldy, like well-smelted gold;and it is both of these because it is well developed, according as it is said: “Bhikkhus, I do not see anyone thing that, when developed and cultivated, becomes so malleable and wieldy as does the mind” (A I 9).

16. It is steady because it is steadied in this purifiedness, and the rest. It is attained to imperturbability (āneñjappatta) precisely because it is steady; it is motionless, without perturbation (niriñjana), is what is meant. Or alternatively, it is steady because steady in its own masterability through malleability and wieldiness, and it is attained to imperturbability because it is reinforced by faith, and so on.

17. For consciousness reinforced by faith is not perturbed by faithlessness; when reinforced by energy, it is not perturbed by idleness; when reinforced by mindfulness, it is not perturbed by negligence; when reinforced by concentration, it is not perturbed by agitation; when reinforced by understanding, it is not perturbed by ignorance; and when illuminated, it is not perturbed by the darkness of defilement. So when it is reinforced by these six states, it is attained to imperturbability.

18. Consciousness possessing these eight factors in this way is susceptible of being directed to the realization by direct-knowledge of states realizable by direct-knowledge.

19. Another method: It is concentrated by means of fourth-jhāna concentration. It is purified by separation from the hindrances. It is bright owing to the surmounting of applied thought and the rest. It is unblemished owing to absence of evil wishes based on the obtainment of jhāna.[3] It is rid of defilement owing to the disappearance of the defilements of the mind consisting in covetousness, etc.; and both of these should be understood according to the Anaṅgaṇa Sutta (MN 5) and the Vattha Sutta (MN 7). It is become malleable by masterability. It is wieldy by reaching the state of a road to power (§50). It is steady and attained to imperturbability by reaching the refinement of completed development; the meaning is that according as it has attained imperturbability so it is steady. And the consciousness possessing these eight factors in this way [378] is susceptible of being directed to the realization by direct-knowledge of states realizable by direct-knowledge, since it is the basis, the proximate cause, for them.

20. He directs, he inclines, his mind to the kinds of supernormal powers (iddhividha—lit. “kinds of success”): here “success” (iddhi) is the success of succeeding (ijjhana); in the sense of production, in the sense of obtainment, is what is meant. For what is produced and obtained is called “successful,” according as it is said, “When a mortal desires, if his desire is fulfilled” (samijjhati) (Sn 766), and likewise: “Renunciation succeeds (ijjhati), thus it is a success (iddhi) … It metamorphoses (paṭiharati) [lust], thus it is a metamorphosis (pāṭihāriya)[4] … The Arahant path succeeds, thus it is a success … It metamorphoses [all defilements], thus it is a metamorphosis” (Paṭis II 229).

21. Another method: success is in the sense of succeeding. That is a term for the effectiveness of the means; for effectiveness of the means succeeds with the production of the result intended, according as it is said: “This householder Citta is virtuous and magnanimous. If he should aspire, ‘Let me in the future become a Wheel-turning Monarch,’ being virtuous, he will succeed in his aspiration, because it is purified” (S IV 303).

22. Another method: beings succeed by its means, thus it is success. They succeed, thus they are successful; they are enriched, promoted, is what is meant.

That [success (power)] is of ten kinds, according as it is said, “Kinds of success: ten kinds of success,” after which it is said further, “What ten kinds of success? Success by resolve, success as transformation, success as the mind-made [body], success by intervention of knowledge, success by intervention of concentration, Noble Ones’ success, success born of kamma result, success of the meritorious, success through the sciences, success in the sense of succeeding due to right exertion applied here or there” (Paṭis II 205).

23. (i) Herein, the success shown in the exposition [of the above summary] thus, “Normally one, he adverts to [himself as] many or a hundred or a thousand or a hundred thousand; having adverted, he resolves with knowledge, “Let me be many” (Paṭis II 207), is called success by resolve because it is produced by resolving.

24. (ii) That given as follows, “Having abandoned his normal form, he shows [himself in] the form of a boy or the form of a serpent … or he shows a manifold military array” (Paṭis II 210), is called success as transformation because of the abandoning and alteration of the normal form. [379]

25. (iii) That given in this way, “Here a bhikkhu creates out of this body another body possessing visible form, mind-made” (Paṭis II 210), is called success as the mind-made (body) because it occurs as the production of another, mind-made, body inside the body.

26. (iv) A distinction brought about by the influence of knowledge either before the arising of the knowledge or after it or at that moment is called success by intervention of knowledge; for this is said: “The meaning (purpose) as abandoning perception of permanence succeeds through contemplation of impermanence, thus it is success by intervention of knowledge … The meaning (purpose) as abandoning all defilements succeeds through the Arahant path, thus it is success by intervention of knowledge. There was success by intervention of knowledge in the venerable Bakkula. There was success by intervention of knowledge in the venerable Saṅkicca. There was success by intervention of knowledge in the venerable Bhūtapāla” (Paṭis II 211).

27. Herein, when the venerable Bakkula as an infant was being bathed in the river on an auspicious day, he fell into the stream through the negligence of his nurse. A fish swallowed him and eventually came to the bathing place at Benares. There it was caught by a fisherman and sold to a rich man’s wife. The fish interested her, and thinking to cook it herself, she slit it open. When she did so, she saw the child like a golden image in the fish’s stomach. She was overjoyed, thinking, “At last I have got a son.” So the venerable Bakkula’s safe survival in a fish’s stomach in his last existence is called “success by intervention of knowledge” because it was brought about by the influence of the Arahant-path knowledge due to be obtained by [him in] that life. But the story should be told in detail (see M-a IV 190).

28. The Elder Saṅkicca’s mother died while he was still in her womb. At the time of her cremation she was pierced by stakes and placed on a pyre. The infant received a wound on the corner of his eye from the point of a stake and made a sound. Then, thinking that the child must be alive, they took down the body and opened its belly. They gave the child to the grandmother. Under her care he grew up, and eventually he went forth and reached Arahantship together with the discriminations. So the venerable Saṅkicca’s safe survival on the pyre is called, “success by intervention of knowledge” in the way just stated (see Dhp-a II 240).

29. The boy Bhūtapāla’s father was a poor man in Rājagaha. [380] He went into the forest with a cart to get a load of wood. It was evening when he returned to the city gate. Then his oxen slipped the yoke and escaped into the city. He seated the child beside the cart and went into the city after the oxen. Before he could come out again, the gate was closed. The child’s safe survival through the three watches of the night outside the city in a place infested by wild beasts and spirits is called, “success by intervention of knowledge” in the way just stated. But the story should be told in detail.

30. (v) A distinction brought about by the influence of serenity either before the concentration or after it or at that moment is called success by intervention of concentration for this is said: “The meaning (purpose) as abandoning the hindrances succeeds by means of the first jhāna, thus it is success by intervention of concentration … The meaning (purpose) as abandoning the base consisting of nothingness succeeds by means of the attainment of the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception, thus it is success by intervention of concentration. There was success by intervention of concentration in the venerable Sāriputta … in the venerable Sañjīva … in the venerable Khāṇu-Kondañña … in the laywoman devotee Uttarā … in the lay-woman devotee Sāmāvatī” (Paṭis II 211–12).

31. Herein, while the venerable Sāriputta was living with the Elder Mahā Moggallāna at Kapotakandarā he was sitting in the open on a moonlit night with his hair newly cut. Then a wicked spirit, though warned by his companion, gave him a blow on the head, the noise of which was like a thunder clap. At the time the blow was given the elder was absorbed in an attainment; consequently he suffered no harm from the blow. This was success by intervention of concentration in that venerable one. The story is given in the Udāna too (Ud 39).

32. While the Elder Sañjīva was in the attainment of cessation, cowherds, etc., who noticed him thought he was dead. They brought grass and sticks and cowdung and set fire to them. Not even a corner of the elder’s robe was burnt. This was success by intervention of concentration in him because it was brought about by the influence of the serenity occurring in his successive attainment [of each of the eight jhānas preceding cessation]. But the story is given in the Suttas too (M I 333).

33. The Elder Khāṇu Kondañña was naturally gifted in attainments. He was sitting absorbed in attainment one night in a certain forest. [381] Five hundred robbers came by with stolen booty. Thinking that no one was following them and needing rest, they put the booty down. Believing the elder was a tree stump (khāṇuka), they piled all the booty on him. The elder emerged at the predetermined time just as they were about to depart after resting, at the very time in fact when the one who had put his booty down first was picking it up. When they saw the elder move, they cried out in fear. The elder said, “Do not be afraid, lay followers; I am a bhikkhu.” They came and paid homage. Such was their confidence in the elder that they went forth into homelessness, and they eventually reached Arahantship together with the discriminations. The absence here of harm to the elder, covered as he was by five hundred bundles of goods, was success by intervention of concentration (see Dhp-a II 254).

34. The laywoman devotee Uttarā was the daughter of a rich man called Puṇṇaka. A harlot called Sirimā who was envious of her, poured a basin of hot oil over her head. At that moment Uttarā had attained [jhāna in], loving-kindness. The oil ran off her like water on a lotus leaf. This was success by intervention of concentration in her. But the story should be given in detail (see Dhp-a III 310; Aa I 451).

35. King Udena’s chief queen was called Sāmāvatī. The brahman Māgaṇḍiya, who aspired to elevate his own daughter to the position of chief queen, put a poisonous snake into Sāmāvatī’s lute. Then he told the king, “Sāmāvatī wants to kill you, sire. She is carrying a poisonous snake about in her lute.” When the king found it, he was furious. Intending to kill her, he took his bow and aimed a poisoned arrow. Sāmāvatī with her retinue pervaded the king with lovingkindness. The king stood trembling, unable either to shoot the arrow or to put it away. Then the queen said to him, “What is it, sire, are you tired?”—“Yes, I am tired.”—“Then put down the bow.” The arrow fell at the king’s feet. Then the queen advised him, “Sire, one should not hate one who has no hate.” So the king’s not daring to release the arrow was success by intervention of concentration in the laywoman Sāmāvatī (see Dhp-a I 216; A-a I 443).

36. (vi) That which consists in dwelling perceiving the unrepulsive in the repulsive, etc., is called Noble Ones’ success, according as it is said: “What is Noble Ones’ success? Here, if a bhikkhu should wish, “May I dwell perceiving the unrepulsive in the repulsive,” he dwells perceiving the unrepulsive in that … he dwells in equanimity towards that, mindful and fully aware” (Paṭis II 212). [382] This is called “Noble Ones’ success” because it is only produced in Noble Ones who have reached mind mastery.

37. For if a bhikkhu with cankers destroyed possesses this kind of success, then when in the case of a disagreeable object he is practicing pervasion with loving-kindness or giving attention to it as elements, he dwells perceiving the unrepulsive; or when in the case of an agreeable object he is practicing pervasion with foulness or giving attention to it as impermanent, he dwells perceiving the repulsive. Likewise, when in the case of the repulsive and unrepulsive he is practicing that same pervasion with loving-kindness or giving attention to it as elements, he dwells perceiving the unrepulsive; and when in the case of the unrepulsive and repulsive he is practicing that same pervasion with foulness or giving attention to it as impermanent, he dwells perceiving the repulsive. But when he is exercising the six-factored equanimity in the following way, “On seeing a visible object with the eye, he is neither glad nor …” (Paṭis II 213), etc., then rejecting both the repulsive and the unrepulsive, he dwells in equanimity, mindful and fully aware.

38. For the meaning of this is expounded in the Paṭisambhidā in the way beginning: “How does he dwell perceiving the unrepulsive in the repulsive? In the case of a disagreeable object he pervades it with loving-kindness or he treats it as elements” (Paṭis II 212). Thus it is called, “Noble Ones’ success” because it is only produced in Noble Ones who have reached mind mastery.

39. (vii) That consisting in travelling through the air in the case of winged birds, etc., is called success born of kamma result, according as it is said: “What is success born of kamma result? That in all winged birds, in all deities, in some human beings, in some inhabitants of states of loss, is success born of kamma result” (Paṭis II 213). For here it is the capacity in all winged birds to travel through the air without jhāna or insight that is success born of kamma result; and likewise that in all deities, and some human beings, at the beginning of the aeon, and likewise that in some inhabitants of states of loss such as the female spirit Piyaṅkara’s mother (see S-a II 509), Uttara’s mother (Pv 140), Phussamittā, Dhammaguttā, and so on.

40. (viii) That consisting in travelling through the air, etc., in the case of Wheelturning Monarchs, etc., is called success of the meritorious, according as it is said: “What is success of the meritorious? The Wheel-turning Monarch travels through the air with his fourfold army, even with his grooms and shepherds. The householder Jotika had the success of the meritorious. The householder Jaṭilaka had the success of the meritorious. [383] The householder Ghosita had the success of the meritorious. The householder Meṇḍaka had the success of the meritorious. That of the five very meritorious is success of the meritorious” (Paṭis II 213). In brief, however, it is the distinction that consists in succeeding when the accumulated merit comes to ripen that is success of the meritorious.

41. A crystal palace and sixty-four wishing trees cleft the earth and sprang into existence for the householder Jotika. That was success of the meritorious in his case (Dhp-a IV 207). A golden rock of eighty cubits [high] was made for Jaṭilaka (Dhp-a IV 216). Ghosita’s safe survival when attempts were made in seven places to kill him was success of the meritorious (Dhp-a I 174). The appearance to Meṇḍaka (= Ram) of rams (meṇḍaka) made of the seven gems in a place the size of one sītā[5] was success of the meritorious in Meṇḍaka (Dhp-a III 364).

42. The “five very meritorious” are the rich man Meṇḍaka, his wife Candapadumasiri, his son the rich man Dhanañjaya, his daughter-in-law Sumanadevī, and his slave Puṇṇa. When the rich man [Meṇḍaka] washed his head and looked up at the sky, twelve thousand five hundred measures were filled for him with red rice from the sky. When his wife took a nāḷi measure of cooked rice, the food was not used up though she served the whole of Jambudīpa with it. When his son took a purse containing a thousand [ducats (kahāpaṇa)], the ducats were not exhausted even though he made gifts to all the inhabitants of Jambudīpa. When his daughter-in-law took a pint (tumba) measure of paddy, the grain was not used up even when she shared it out among all the inhabitants of Jambudīpa. When the slave ploughed with a single ploughshare, there were fourteen furrows, seven on each side (see Vin I 240; Dhp-a I 384). This was success of the meritorious in them.

43. (ix) That beginning with travelling through the air in the case of masters of the sciences is success through the sciences, according as it is said: “What is success through the sciences? Masters of the sciences, having pronounced their scientific spells, travel through the air, and they show an elephant in space, in the sky … and they show a manifold military array” (Paṭis II 213).

44. (x) But the succeeding of such and such work through such and such right exertion is success in the sense of succeeding due to right exertion applied here or there, according as it is said: “The meaning (purpose) of abandoning lust succeeds through renunciation, thus it is success in the sense of succeeding due to right exertion applied here or there … The meaning (purpose) of abandoning all defilements succeeds through the Arahant path, thus it is success in the sense of succeeding due to right exertion applied here or there” (Paṭis II 213). [384] And the text here is similar to the previous text in the illustration of right exertion, in other words, the way. But in the Commentary it is given as follows: “Any work belonging to a trade such as making a cart assemblage, etc., any medical work, the learning of the Three Vedas, the learning of the Three Piṭakas, even any work connected with ploughing, sowing, etc.—the distinction produced by doing such work is success in the sense of succeeding due to right exertion applied here or there.”

45. So, among these ten kinds of success, only (i) success by resolve is actually mentioned in the clause “kinds of supernormal power (success),” but (ii) success as transformation and (iii) success as the mind-made [body] are needed in this sense as well.

46. (i) To the kinds of supernormal power (see §20): to the components of supernormal power, or to the departments of supernormal power. He directs, he inclines, his mind: when that bhikkhu’s consciousness has become the basis for direct-knowledge in the way already described, he directs the preliminary-work consciousness with the purpose of attaining the kinds of supernormal power, he sends it in the direction of the kinds of supernormal power, leading it away from the kasiṇa as its object. Inclines: makes it tend and lean towards the supernormal power to be attained.

47. He: the bhikkhu who has done the directing of his mind in this way. The various: varied, of different sorts. Kinds of supernormal power: departments of supernormal power. Wields: paccanubhoti = paccanu-bhavati (alternative form); the meaning is that he makes contact with, realizes, reaches.

48. Now, in order to show that variousness, it is said: “Having been one, [he becomes many; having been many, he becomes one. He appears and vanishes. He goes unhindered through walls, through enclosures, through mountains, as though in open space. He dives in and out of the earth as though in water. He goes on unbroken water as though on earth. Seated cross-legged he travels in space like a winged bird. With his hand he touches and strokes the moon and sun so mighty and powerful. He wields bodily mastery even as far as the Brahmā-world]” (D I 77).

Herein, having been one: having been normally one before giving effect to the supernormal power. He becomes many: wanting to walk with many or wanting to do a recital or wanting to ask questions with many, he becomes a hundred or a thousand. But how does he do this? He accomplishes, (1) the four planes, (2) the four bases (roads), (3) the eight steps, and (4) the sixteen roots of supernormal power, and then he (5) resolves with knowledge.

49. 1. Herein, the four planes should be understood as the four jhānas; for this has been said by the General of the Dhamma [the Elder Sāriputta]: “What are the four planes of supernormal power? They are the first jhāna as the plane born of seclusion, the second jhāna as the plane of happiness and bliss, the third jhāna as the plane of equanimity and bliss, the fourth jhāna as the plane of neither pain nor pleasure. These four planes of supernormal power lead to the attaining of supernormal power, to the obtaining of supernormal power, to the transformation due to supernormal power, to the majesty[6] of supernormal power, to the mastery of supernormal power, to fearlessness in supernormal power” (Paṭis II 205). And he reaches supernormal power by becoming light, malleable and wieldy in the body after steeping himself in blissful perception and light perception due to the pervasion of happiness and pervasion of bliss, [385] which is why the first three jhānas should be understood as the accessory plane since they lead to the obtaining of supernormal power in this manner. But the fourth is the natural plane for obtaining supernormal power.

50. 2. The four bases (roads) should be understood as the four bases of success (iddhi-pāda—roads to power); for this is said: “What are the four bases (pāda—roads) for success (iddhi—power)? Here a bhikkhu develops the basis for success (road to power) that possesses both concentration due to zeal and the will to strive (endeavour); he develops the basis for success (road to power) that possesses both concentration due to energy and the will to strive; he develops the basis for success (road to power) that possesses both concentration due to [natural purity of] consciousness and the will to strive; he develops the basis for success (road to power) that possesses both concentration due to inquiry and the will to strive. These four bases (roads) for success (power) lead to the obtaining of supernormal power (success) … to the fearlessness due to supernormal power (success)” (Paṭis II 205).

51. And here the concentration that has zeal as its cause, or has zeal outstanding,is concentration due to zeal; this is a term for concentration obtained by giving precedence to zeal consisting in the desire to act. Will (formation) as endeavour is will to strive; this is a term for the energy of right endeavour accomplishing its fourfold function (see §53). Possesses: is furnished with concentration due to zeal and with the [four] instances of the will to strive.

52. Road to power (basis for success): the meaning is, the total of consciousness and its remaining concomitants [except the concentration and the will], which are, in the sense of resolve, the road to (basis for) the concentration due to zeal and will to strive associated with the direct-knowledge consciousness, which latter are themselves termed “power (success)” either by treatment as “production” (§20) or in the sense of “succeeding” (§21) or by treatment in this way, “beings succeed by its means, thus they are successful; they are enriched, promoted” (§22). For this is said: “Basis for success (road to power): it is the feeling aggregate, [perception aggregate, formations aggregate, and] consciousness aggregate, in one so become” (Vibh 217).

53. Or alternatively: it is arrived at (pajjate) by means of that, thus that is a road (pāda—basis); it is reached, is the meaning. Iddhi-pāda = iddhiyā pāda (resolution of compound): this is a term for zeal, etc., according as it is said: “Bhikkhus, if a bhikkhu obtains concentration, obtains unification of mind supported by zeal, this is called concentration due to zeal. He [awakens zeal] for the non-arising of unarisen evil, unprofitable states, [strives, puts forth energy, strains his mind and] struggles. [He awakens zeal for the abandoning of arisen evil, unprofitable states … He awakens zeal for the arousing of unarisen profitable states … He awakens zeal for the maintenance, non-disappearance, increase, growth, development and perfection of arisen profitable states, strives, puts forth energy, strains his mind and struggles]. These are called instances of the will to strive. So this zeal and this concentration due to zeal and these [four] instances of will to strive are called the road to power (basis for success) that possesses concentration due to zeal and the will to strive” (S V 268). And the meaning should be understood in this way in the case of the other roads to power (bases for success).[7]

54. 3. The eight steps should be understood as the eight beginning with zeal; for this is said: “What are the eight steps? If a bhikkhu obtains concentration, obtains unification of mind supported by zeal, then the zeal is not the concentration; the concentration is not the zeal. [386] The zeal is one, the concentration is another. If a bhikkhu … supported by energy … supported by [natural purity of] consciousness … supported by inquiry … then the inquiry is not the concentration; the concentration is not the inquiry. The inquiry is one, the concentration is another. These eight steps to power lead to the obtaining of supernormal power (success) … to fearlessness due to supernormal power (success)” (Paṭis II 205). For here it is the zeal consisting in the desire to arouse supernormal power (success), which zeal is joined with concentration, that leads to the obtaining of the supernormal power. Similarly in the case of energy, and so on. That should be understood as the reason why they are called the “eight steps.”

55. 4. The sixteen roots: the mind’s unperturbedness[8] should be understood in sixteen modes, for this is said: “What are the sixteen roots of success (power)? Undejected consciousness is not perturbed by indolence, thus it is unperturbed. Unelated consciousness is not perturbed by agitation, thus it is unperturbed. Unattracted consciousness is not perturbed by greed, thus it is unperturbed. Unrepelled consciousness is not perturbed by ill will, thus it is unperturbed. Independent consciousness is not perturbed by [false] view, thus it is unperturbed. Untrammelled consciousness is not perturbed by greed accompanied by zeal, thus it is unperturbed. Liberated consciousness is not perturbed by greed for sense desires, thus it is unperturbed. Unassociated consciousness is not perturbed by defilement, thus it is unperturbed. Consciousness rid of barriers is not perturbed by the barrier of defilement, thus it is unperturbed. Unified consciousness is not perturbed by the defilement of variety, thus it is unperturbed. Consciousness reinforced by faith is not perturbed by faithlessness, thus it is unperturbed. Consciousness reinforced by energy is not perturbed by indolence, thus it is unperturbed. Consciousness reinforced by mindfulness is not perturbed by negligence, thus it is unperturbed. Consciousness reinforced by concentration is not perturbed by agitation, thus it is unperturbed. Consciousness reinforced by understanding is not perturbed by ignorance, thus it is unperturbed. Illuminated consciousness is not perturbed by the darkness of ignorance, thus it is unperturbed. These sixteen roots of success (power) lead to the obtaining of supernormal power (success) … to fearlessness due to supernormal power (success)” (Paṭis II 206).

56. Of course, this meaning is already established by the words, “When his concentrated mind,” etc., too, but it is stated again for the purpose of showing that the first jhāna, etc., are the three planes, bases (roads), steps, and roots, of success (to supernormal powers). And the first-mentioned method is the one given in the Suttas, but this is how it is given in the Paṭisambhidā. So it is stated again for the purpose of avoiding confusion in each of the two instances.

57. 5. He resolves with knowledge (§48): when he has accomplished these things consisting of the planes, bases (roads), steps, and roots, of success (to supernormal power), [387] then he attains jhāna as the basis for direct-knowledge and emerges from it. Then if he wants to become a hundred, he does the preliminary work thus, “Let me become a hundred, let me become a hundred,” after which he again attains jhāna as basis for direct-knowledge, emerges, and resolves. He becomes a hundred simultaneously with the resolving consciousness. The same method applies in the case of a thousand, and so on. If he does not succeed in this way, he should do the preliminary work again, and attain, emerge, and resolve a second time. For it is said in the Saṃyutta Commentary that it is allowable to attain once, or twice.

58. Herein, the basic-jhāna consciousness has the sign as its object;but the preliminary-work consciousnesses have the hundred as their object or the thousand as their object. And these latter are objects as appearances, not as concepts. The resolving consciousness has likewise the hundred as its object or the thousand as its object. That arises once only, next to change-of-lineage [consciousness], as in the case of absorption consciousness already described (IV.78), and it is fine-material-sphere consciousness belonging to the fourth jhāna.

59. Now, it is said in the Paṭisambhidā: “Normally one, he adverts to [himself as] many or a hundred or a thousand or a hundred thousand; having adverted, he resolves with knowledge, ‘Let me be many.’ He becomes many, like the venerable Cūḷa-Panthaka” (Paṭis II 207). Here he adverts is said with respect only to the preliminary work. Having adverted, he resolves with knowledge is said with respect to the knowledge of the direct-knowledge. Consequently, he adverts to many. After that he attains with the last one of the preliminary-work consciousnesses. After emerging from the attainment, he again adverts thus, “Let me be many,” after which he resolves by means of the single [consciousness] belonging to the knowledge of direct-knowledge, which has arisen next to the three, or four, preparatory consciousnesses that have occurred, and which has the name “resolve” owing to its making the decision. This is how the meaning should be understood here.

60. Like the venerable Cūḷa-Panthaka is said in order to point to a bodily witness of this multiple state; but that must be illustrated by the story. There were two brothers, it seems, who were called, “Panthaka (Roadling)” because they were born on a road. The senior of the two was called Mahā-Panthaka. He went forth into homelessness and reached Arahantship together with the discriminations. When he had become an Arahant, he made Cūḷa-Panthaka go forth too, and he set him this stanza: [388]

As a scented kokanada lotus

Opens in the morning with its perfume,

See the One with Radiant Limbs who glitters[9]

Like the sun’s orb blazing in the heavens (A III 239; S I 81).

Four months went by, but he could not get it by heart. Then the elder said, “You are useless in this dispensation,” and he expelled him from the monastery.

61. At that time the elder had charge of the allocation of meal [invitations]. Jīvaka approached the elder, saying, “Take alms at our house, venerable sir, together with the Blessed One and five hundred bhikkhus.” The elder consented, saying, “I accept for all but Cūḷa-Panthaka.” Cūḷa-Panthaka stood weeping at the gate. The Blessed One saw him with the divine eye, and he went to him. “Why are you weeping?” he asked, and he was told what had happened.

62. The Blessed One said, “No one in my dispensation is called useless for being unable to do a recitation. Do not grieve, bhikkhu.” Taking him by the arm, he led him into the monastery. He created a piece of cloth by supernormal power and gave it to him, saying, “Now, bhikkhu, keep rubbing this and recite over and over again: ‘Removal of dirt, removal of dirt.’” While doing as he had been told, the cloth became black in colour. What he came to perceive was this: “The cloth is clean; there is nothing wrong there. It is this selfhood that is wrong.” He brought his knowledge to bear on the five aggregates, and by increasing insight he reached the neighbourhood of conformity [knowledge] and change-of-lineage [knowledge].

63. Then the Blessed One uttered these illuminative stanzas:

Now greed it is, not dust, that we call “dirt,”

And “dirt” is just a term in use for greed;

This greed the wise reject, and they abide

Keeping the Law of him that has no greed.

Now, hate it is, not dust, that we call “dirt,”

… … …

Delusion too, it is not dust, that we call “dirt,”

And “dirt” is just a term used for delusion;

Delusion the wise reject, and they abide

Keeping the Dhamma of him without delusion (Nidd I 505). [389]

When the stanzas were finished, the venerable Cūḷa-Panthaka had at his command the nine supramundane states attended by the four discriminations and six kinds of direct-knowledge.

64. On the following day the Master went to Jīvaka’s house together with the Community of Bhikkhus. Then when the gruel was being given out at the end of the water-offering ceremony,[10] he covered his bowl. Jīvaka asked, “What is it, venerable sir?”—“There is a bhikkhu at the monastery.” He sent a man, telling him, “Go, and return quickly with the lord.” 65. When the Blessed One had left the monastery:

Now, having multiplied himself

Up to a thousand, Panthaka Sat in the pleasant mango wood until the time should be announced (Th 563).

66. When the man went and saw the monastery all glowing with yellow, he returned and said, “Venerable sir, the monastery is crowded with bhikkhus. I do not know which of them the lord is.” Then the Blessed One said, “Go and catch hold of the hem of the robe of the first one you see, tell him, ‘The Master calls you’ and bring him here.” He went and caught hold of the elder’s robe. At once all the creations vanished. The elder dismissed him, saying, “You may go,” and when he had finished attending to his bodily needs such as mouth washing, he arrived first and sat down on the seat prepared.

It was with reference to this that it was said, “like the venerable Cūḷa-Panthaka.”

67. The many who were created there were just like the possessor of the supernormal power because they were created without particular specification. Then whatever the possessor of the supernormal powers does, whether he stands, sits, etc., or speaks, keeps silent, etc., they do the same. But if he wants to make them different in appearance, some in the first phase of life, some in the middle phase, and some in the last phase, and similarly some long-haired, some half-shaved, some shaved, some grey-haired, some with lightly dyed robes, some with heavily dyed robes, or expounding phrases, explaining Dhamma, intoning, asking questions, answering questions, cooking dye, sewing and washing robes, etc., or if he wants to make still others of different kinds, he should emerge from the basic jhāna, do the preliminary work in the way beginning ‘Let there be so many bhikkhus in the first phase of life’, etc.; then he should once more attain and emerge, and then resolve. They become of the kinds desired simultaneously with the resolving consciousness.[11]

68. The same method of explanation applies to the clause having been many, he becomes one: but there is this difference. After this bhikkhu thus created a manifold state, then he again thinks, “As one only I will walk about, do a recital, [390] ask a question,” or out of fewness of wishes he thinks, “This is a monastery with few bhikkhus. If someone comes, he will wonder, ‘Where have all these bhikkhus who are all alike come from? Surely it will be one of the elder’s feats?’ and so he might get to know about me.” Meanwhile, wishing, “Let me be one only,” he should attain the basic jhāna and emerge. Then, after doing the preliminary work thus, “Let me be one,” he should again attain and emerge and then resolve thus, ‘Let me be one’. He becomes one simultaneously with the resolving consciousness. But instead of doing this, he can automatically become one again with the lapse of the predetermined time.

69. He appears and vanishes: the meaning here is that he causes appearance, causes vanishing. For it is said in the Paṭisambhidā with reference to this: “‘He appears’: he is not veiled by something, he is not hidden, he is revealed, he is evident. ‘Vanishes’: he is veiled by something, he is hidden, he is shut away, he is enclosed” (Paṭis II 207).[12]

Now, this possessor of supernormal power who wants to make an appearance, makes darkness into light, or he makes revealed what is hidden, or he makes what has not come into the visual field come into the visual field.

70. How? If he wants to make himself or another visible even though hidden or at a distance, he emerges from the basic jhāna and adverts thus, “Let this that is dark become light” or “Let this that is hidden be revealed” or “Let this that has not come into the visual field come into the visual field.” Then he does the preliminary work and resolves in the way already described. It becomes as resolved simultaneously with the resolve. Others then see even when at a distance; and he himself sees too, if he wants to see.

71. But by whom was this miracle formerly performed? By the Blessed One. For when the Blessed One had been invited by Cūḷa-Subhaddā and was traversing the seven-league journey between Sāvatthī and Sāketa with five hundred palanquins[13] created by Vissakamma (see Dhp-a III 470), he resolved in suchwise that citizens of Sāketa saw the inhabitants of Sāvatthī and citizens of Sāvatthī saw the inhabitants of Sāketa. And when he had alighted in the centre of the city, he split the earth in two and showed Avīci, and he parted the sky in two and showed the Brahmā-world.

72. And this meaning should also be explained by means of the Descent of the Gods (devorohaṇa). When the Blessed One, it seems, had performed the Twin Miracle[14] and had liberated eighty-four thousand beings from bonds, he wondered, “Where did the past Enlightened Ones go to when they had finished the Twin Miracle?” He saw that they had gone to the heaven of the Thirty-three. [391] Then he stood with one foot on the surface of the earth, and placed the second on Mount Yugandhara. Then again he lifted his first foot and set it on the summit of Mount Sineru. He took up the residence for the Rains there on the Red Marble Terrace, and he began his exposition of the Abhidhamma, starting from the beginning, to the deities of ten thousand world-spheres. At the time for wandering for alms he created an artificial Buddha to teach the Dhamma.

73. Meanwhile the Blessed One himself would chew a tooth-stick of nāgalatā wood and wash his mouth in Lake Anotatta. Then, after collecting alms food among the Uttarakurus, he would eat it on the shores of that lake. [Each day] the Elder Sāriputta went there and paid homage to the Blessed One, who told him, “Today I taught this much Dhamma,” and he gave him the method. In this way he gave an uninterrupted exposition of the Abhidhamma for three months. Eighty million deities penetrated the Dhamma on hearing it.

74. At the time of the Twin Miracle an assembly gathered that was twelve leagues across. Then, saying, “We will disperse when we have seen the Blessed One,” they made an encampment and waited there. Anāthapiṇḍika the Lesser[15] supplied all their needs. People asked the Elder Anuruddha to find out where the Blessed One was. The elder extended light, and with the divine eye he saw where the Blessed One had taken up residence for the Rains. As soon as he saw this, he announced it.

75. They asked the venerable Mahā Moggallāna to pay homage to the Blessed One. In the midst of the assembly the elder dived into the earth. Then cleaving Mount Sineru, he emerged at the Perfect One’s feet, and he paid homage at the Blessed One’s feet. This is what he told the Blessed One: “Venerable sir, the inhabitants of Jambudīpa pay homage at the Blessed One’s feet, and they say, ‘We will disperse when we have seen the Blessed One.’” The Blessed One said, “But, Moggallāna, where is your elder brother, the General of the Dhamma?”—“At the city of Saṅkassa, venerable sir.”—“Moggallāna, those who wish to see me should come tomorrow to the city of Saṅkassa. Tomorrow being the Uposatha day of the full moon, I shall descend to the city of Saṅkassa for the Mahāpavāraṇā ceremony.”

76. Saying, “Good, venerable sir,” the elder paid homage to Him of the Ten Powers, and descending by the way he came, he reached the human neighbourhood. And at the time of his going and coming he resolved that people should see it. This, firstly, is the miracle of becoming apparent that the Elder Mahā Moggallāna performed here. Having arrived thus, he related what had happened, and he said, “Come forth after the morning meal and pay no heed to distance” [thus promising that they would be able to see in spite of the distance].

77. The Blessed One informed Sakka, Ruler of Gods, “Tomorrow, O King, I am going to the human world.” The Ruler of Gods [392] commanded Vissakamma, “Good friend, the Blessed One wishes to go to the human world tomorrow. Build three flights of stairs, one of gold, one of silver and one of crystal.” He did so.

78. On the following day the Blessed One stood on the summit of Sineru and surveyed the eastward world element. Many thousands of world-spheres were visible to him as clearly as a single plain. And as the eastward world element, so too he saw the westward, the northward and the southward world elements all clearly visible. And he saw right down to Avīci, and up to the Realm of the Highest Gods. That day, it seems, was called the day of the Revelation of Worlds (loka-vivaraṇa). Human beings saw deities, and deities saw human beings. And in doing so the human beings did not have to look up or the deities down. They all saw each other face to face.

79. The Blessed One descended by the middle flight of stairs made of crystal; the deities of the six sense-sphere heavens by that on the left side made of gold; and the deities of the Pure Abodes, and the Great Brahmā, by that on the right side made of silver. The Ruler of Gods held the bowl and robe. The Great Brahmā held a three-league-wide white parasol. Suyāma held a yak-tail fan. Five-crest (Pañcasikha), the son of the gandhabba, descended doing honour to the Blessed One with his bael-wood lute measuring three quarters of a league. On that day there was no living being present who saw the Blessed One but yearned for enlightenment. This is the miracle of becoming apparent that the Blessed One performed here.

80. Furthermore, in Tambapaṇṇi Island (Sri Lanka), while the Elder Dhammadinna, resident of Taḷaṅgara, was sitting on the shrine terrace in the Great Monastery of Tissa (Tissamahāvihāra) expounding the Apaṇṇaka Sutta, “Bhikkhus, when a bhikkhu possesses three things he enters upon the untarnished way” (A I 113), he turned his fan face downwards and an opening right down to Avīci appeared. Then he turned it face upwards and an opening right up to the Brahmā-world appeared. Having thus aroused fear of hell and longing for the bliss of heaven, the elder taught the Dhamma. Some became stream-enterers, some once-returners, some non-returners, some Arahants.

81. But one who wants to cause a vanishing makes light into darkness, or he hides what is unbidden, or he makes what has come into the visual field come no more into the visual field. How? If he wants to make himself or another invisible even though unconcealed or nearby, he emerges from the basic jhāna and adverts thus, “Let this light become darkness” or [393] “Let this that is unhidden be hidden” or “Let this that has come into the visual field not come into the visual field.” Then he does the preliminary work and resolves in the way already described. It becomes as he has resolved simultaneously with the resolution. Others do not see even when they are nearby. He too does not see, if he does not want to see.

82. But by whom was this miracle formerly performed? By the Blessed One. For the Blessed One so acted that when the clansman Yasa was sitting beside him, his father did not see him (Vin I 16). Likewise, after travelling two thousand leagues to meet [King] Mahā Kappina and establishing him in the fruition of non-return and his thousand ministers in the fruition of stream-entry, he so acted that Queen Anojā, who had followed the king with a thousand women attendants and was sitting nearby, did not see the king and his retinue. And when he was asked, “Have you seen the king, venerable sir?,” he asked, But which is better for you, to seek the king or to seek [your] self?” (cf. Vin I 23). She replied, “[My] self, venerable sir.” Then he likewise taught her the Dhamma as she sat there, so that, together with the thousand women attendants, she became established in the fruition of stream-entry, while the ministers reached the fruition of non-return, and the king that of Arahantship (see A-a I 322; Dhp-a II 124).

83. Furthermore, this was performed by the Elder Mahinda, who so acted on the day of his arrival in Tambapaṇṇi Island that the king did not see the others who had come with him (see Mahāvaṃsa I 103).

84. Furthermore, all miracles of making evident are called an appearance, and all miracles of making unevident are called a vanishing. Herein, in the miracle of making evident, both the supernormal power and the possessor of the supernormal power are displayed. That can be illustrated with the Twin Miracle; for in that both are displayed thus: “Here the Perfect One performs the Twin Miracle, which is not shared by disciples. He produces a mass of fire from the upper part of his body and a shower of water from the lower part of his body …” (Paṭis I 125). In the case of the miracle of making unevident, only the supernormal power is displayed, not the possessor of the supernormal power. That can be illustrated by means of the Mahaka Sutta (S IV 200), and the Brahmanimantanika Sutta (M I 330). For there it was only the supernormal power of the venerable Mahaka and of the Blessed One respectively that was displayed, not the possessors of the supernormal power, according as it is said:

85. “When he had sat down at one side, the householder Citta said to the venerable Mahaka, ‘Venerable sir, it would be good if the lord would show me a miracle of supernormal power belonging to the higher than human state.’—‘Then, householder, spread your upper robe out on the terrace [394] and scatter[16] a bundle of hay on it.’—‘Yes, venerable sir,’ the householder replied to the venerable Mahaka, and he spread out his upper robe on the terrace and scattered a bundle of hay on it. Then the venerable Mahaka went into his dwelling and fastened the latch, after which he performed a feat of supernormal power such that flames came out from the keyhole and from the gaps in the fastenings and burned the hay without burning the upper robe” (S IV 290).

86. Also according as it is said: “Then, bhikkhus, I performed a feat of supernormal power such that Brahmā and Brahmā’s retinue, and those attached to Brahmā’s retinue might hear my voice and yet not see me, and having vanished in this way, I spoke this stanza:

I saw the fear in [all kinds of] becoming,

Including becoming that seeks non-becoming;

And no becoming do I recommend;

I cling to no delight therein at all (M I 330).

87. He goes unhindered through walls, through enclosures, through mountains, as though in open space: here through walls is beyond walls; the yonder side of a wall, is what is meant. So with the rest. And wall is a term for the wall of a house; enclosure is a wall surrounding a house, monastery (park), village, etc.; mountain is a mountain of soil or a mountain of stone. Unhindered: not sticking. As though in open space: just as if he were in open space.

88. One who wants to go in this way should attain the space-kasiṇa [jhāna] and emerge, and then do the preliminary work by adverting to the wall or the enclosure or some such mountain as Sineru or the World-sphere Mountains, and he should resolve, “Let there be space.” It becomes space only; it becomes hollow for him if he wants to go down or up; it becomes cleft for him if he wants to penetrate it. He goes through it unhindered.

89. But here the Elder Tipiṭaka Cūḷa-Abhaya said: “Friends, what is the use of attaining the space-kasiṇa [jhāna]? Does one who wants to create elephants, horses, etc., attain an elephant-kasiṇa jhāna or horse-kasiṇa jhāna, and so on? Surely the only standard is mastery in the eight attainments, and after the preliminary work has been done on any kasiṇa, it then becomes whatever he wishes.” The bhikkhus said, “Venerable sir, only the space kasiṇa has been given in the text, so it should certainly be mentioned.”

90. Here is the text: “He is normally an obtainer of the space-kasiṇa attainment. He adverts: “Through the wall, through the enclosure, through the mountain.” [395] Having adverted, he resolves with knowledge: “Let there be space.” There is space. He goes unhindered through the wall, through the enclosure, through the mountain. Just as men normally not possessed of supernormal power go unhindered where there is no obstruction or enclosure, so too this possessor of supernormal power, by his attaining mental mastery, goes unhindered through the wall, through the enclosure, through the mountain, as though in open space” (Paṭis II 208).

91. What if a mountain or a tree is raised in this bhikkhu’s way while he is travelling along after resolving; should he attain and resolve again?—There is no harm in that. For attaining and resolving again is like taking the dependence (see Vin I 58; II 274) in the preceptor’s presence. And because this bhikkhu has resolved, “Let there be space,” there will be only space there, and because of the power of his first resolve it is impossible that another mountain or tree can have sprung up meanwhile made by temperature. However, if it has been created by another possessor of supernormal power and created first, it prevails; the former must go above or below it.

92. He dives in and out of the ground (pathaviyā pi ummujjanimmujjaṃ): here it is rising up that is called “diving out” (ummujja) and it is sinking down that is called “diving in” (nimmujja). Ummujjanimmujjaṃ = ummujjañ ca nimmujjañ ca (resolution of compound).

One who wants to do this should attain the water-kasiṇa [jhāna] and emerge. Then he should do the preliminary work, determining thus, “Let the earth in such an area be water,” and he should resolve in the way already described. Simultaneously with the resolve, that much extent of earth according as determined becomes water only. It is there he does the diving in and out.

93. Here is the text: “He is normally an obtainer of the water-kasiṇa attainment. He adverts to earth. Having adverted, he resolves with knowledge: “Let there be water.” There is water. He does the diving in and out of the earth. Just as men normally not possessed of supernormal power do diving in and out of water, so this possessor of supernormal power, by his attaining mental mastery, does the diving in and out of the earth as though in water” (Paṭis II 208).

94. And he does not only dive in and out, but whatever else he wants, such as bathing, drinking, mouth washing, washing of chattels, and so on. And not only water, but there is whatever else (liquid that) he wants, such as ghee, oil, honey, molasses, and so on. When he does the preliminary work, after adverting thus, “Let there be so much of this and this” and resolves, [396] it becomes as he resolved. If he takes them and fills dishes with them, the ghee is only ghee, the oil, etc., only oil, etc., the water only water. If he wants to be wetted by it, he is wetted, if he does not want to be wetted by it, he is not wetted. And it is only for him that that earth becomes water, not for anyone else. People go on it on foot and in vehicles, etc., and they do their ploughing, etc., there. But if he wishes, “Let it be water for them too,” it becomes water for them too. When the time determined has elapsed, all the extent determined, except for water originally present in water pots, ponds, etc., becomes earth again.

95. On unbroken water: here water that one sinks into when trodden on is called “broken,” the opposite is called “unbroken.” But one who wants to go in this way should attain the earth-kasiṇa [jhāna] and emerge. Then he should do the preliminary work, determining thus, “Let the water in such an area become earth,” and he should resolve in the way already described. Simultaneously with the resolve, the water in that place becomes earth. He goes on that.

96. Here is the text: “He is normally an obtainer of the earth-kasiṇa attainment. He adverts to water. Having adverted, he resolves with knowledge: ‘Let there be earth.’ There is earth. He goes on unbroken water. Just as men normally not possessed of supernormal power go on unbroken earth, so this possessor of supernormal power, by his attaining of mental mastery, goes on unbroken water as if on earth” (Paṭis II 208).

97. And he not only goes, but he adopts whatever posture he wishes. And not only earth, but whatever else [solid that] he wants such as gems, gold, rocks, trees, etc. he adverts to that and resolves, and it becomes as he resolves. And that water becomes earth only for him; it is water for anyone else. And fishes and turtles and water birds go about there as they like. But if he wishes to make it earth for other people, he does so too. When the time determined has elapsed, it becomes water again.

98. Seated cross-legged he travels: he goes seated cross-legged. Like a winged bird: like a bird furnished with wings. One who wants to do this should attain the earth kasiṇa and emerge. [397] Then if he wants to go cross-legged, he should do the preliminary work and determine an area the size of a seat for sitting cross-legged on, and he should resolve in the way already described. If he wants to go lying down, he determines an area the size of a bed. If he wants to go on foot, he determines a suitable area the size of a path, and he resolves in the way already described: “Let it be earth.” Simultaneously with the resolve it becomes earth.

99. Here is the text: “‘Seated cross-legged he travels in space like a winged bird’: he is normally an obtainer of the earth-kasiṇa attainment. He adverts to space. Having adverted, he resolves with knowledge: ‘Let there be earth.’ There is earth. He travels (walks), stands, sits, and lies down in space, in the sky. Just as men normally not possessed of supernormal power travel (walk), stand, sit, and lie down on earth, so this possessor of supernormal power, by his attaining of mental mastery, travels (walks), stands, sits, and lies down in space, in the sky” (Paṭis II 208).

100. And a bhikkhu who wants to travel in space should be an obtainer of the divine eye. Why? On the way there may be mountains, trees, etc., that are temperature-originated, or jealous nāgas, supaṇṇas, etc., may create them. He will need to be able to see these. But what should be done on seeing them? He should attain the basic jhāna and emerge, and then he should do the preliminary work thus, “Let there be space,” and resolve.

101. But the Elder [Tipiṭaka Cūḷa-Abhaya] said: “Friends, what is the use of attaining the attainment? Is not his mind concentrated? Hence any area that he has resolved thus, ‘Let it be space’ is space.” Though he spoke thus, nevertheless the matter should be treated as described under the miracle of going unhindered through walls. Moreover, he should be an obtainer of the divine eye for the purpose of descending in a secluded place, for if he descends in a public place, in a bathing place, or at a village gate, he is exposed to the multitude. So, seeing with the divine eye, he should avoid a place where there is no open space and descend in an open space.

102. With his hand he touches and strokes the moon and sun so mighty and powerful: here the “might” of the moon and sun should be understood to consist in the fact that they travel at an altitude of forty-two thousand leagues, and their “power” to consist in their simultaneous illuminating of three [of the four] continents. [398] Or they are “mighty” because they travel overhead and give light as they do, and they are “powerful” because of that same might. He touches: he seizes, or he touches in one place. Strokes: he strokes all over, as if it were the surface of a looking-glass.

103. This supernormal power is successful simply through the jhāna that is made the basis for direct-knowledge; there is no special kasiṇa attainment here. For this is said in the Paṭisambhidā: “‘With his hand … so mighty and powerful’: here this possessor of supernormal power who has attained mind mastery … adverts to the moon and sun. Having adverted, he resolves with knowledge: ‘Let it be within hand’s reach.’ It is within hand’s reach. Sitting or lying down, with his hand he touches, makes contact with, strokes the moon and sun. Just as men normally not possessed of supernormal power touch, make contact with, stroke, some material object within hand’s reach, so this possessor of supernormal power, by his attaining of mental mastery, sitting or lying down, with his hands touches, makes contact with, strokes the moon and sun” (Paṭis II 298).

104. If he wants to go and touch them, he goes and touches them. But if he wants to touch them here sitting or lying down, he resolves: “Let them be within hand’s reach. Then he either touches them as they stand within hand’s reach when they have come by the power of the resolve like palmyra fruits loosened from their stalk, or he does so by enlarging his hand. But when he enlarges his hand, does he enlarge what is clung to or what is not clung to? He enlarges what is not clung to supported by what is clung to.

105. Here the Elder Tipiṭaka Cūḷa-Nāga said: “But, friends, why does what is clung to not become small and big too? When a bhikkhu comes out through a keyhole, does not what is clung to become small? And when he makes his body big, does it not then become big, as in the case of the Elder Mahā Moggallāna?”

106. At one time, it seems, when the householder Anāthapiṇḍika had heard the Blessed One preaching the Dhamma, he invited him thus, Venerable sir, take alms at our house together with five hundred bhikkhus,” and then he departed. The Blessed One consented. When the rest of that day and part of the night had passed, he surveyed the ten-thousandfold world element in the early morning. Then the royal nāga (serpent) called Nandopananda came within the range of his knowledge.

107. The Blessed One considered him thus: “This royal nāga has come into the range of my knowledge. Has he the potentiality for development?” Then he saw that he had wrong view and no confidence in the Three Jewels. [399] He considered thus, “Who is there that can cure him of his wrong view?” He saw that the Elder Mahā Moggallāna could. Then when the night had turned to dawn, after he had seen to the needs of the body, he addressed the venerable Ānanda: “Ānanda, tell five hundred bhikkhus that the Perfect One is going on a visit to the gods.”

108. It was on that day that they had got a banqueting place ready for Nandopananda. He was sitting on a divine couch with a divine white parasol held aloft, surrounded by the three kinds of dancers[17] and a retinue of nāgas, and surveying the various kinds of food and drink served up in divine vessels. Then the Blessed One so acted that the royal nāga saw him as he proceeded directly above his canopy in the direction of the divine world of the Thirty-three, accompanied by the five hundred bhikkhus.

109. Then this evil view arose in Nandopananda the royal nāga: “There go these bald-headed monks in and out of the realm of the Thirty-three directly over my realm. I will not have them scattering the dirt off their feet on our heads.” He got up, and he went to the foot of Sineru. Changing his form, he surrounded it seven times with his coils. Then he spread his hood over the realm of the Thirtythree and made everything there invisible.

110. The venerable Raṭṭhapāla said to the Blessed One: “Venerable sir, standing in this place formerly I used to see Sineru and the ramparts of Sineru,[18] and the Thirty-three, and the Vejayanta Palace, and the flag over the Vejayanta Palace. Venerable sir, what is the cause, what is the reason, why I now see neither Sineru nor … the flag over the Vejayanta Palace?”—“This royal nāga called Nandopananda is angry with us, Raṭṭhapāla. He has surrounded Sineru seven times with his coils, and he stands there covering us with his raised hood, making it dark.”—“I will tame him, venerable sir.” But the Blessed One would not allow it. Then the venerable Bhaddiya and the venerable Rāhula and all the bhikkhus in turn offered to do so, but the Blessed One would not allow it.

111. Last of all the venerable Mahā Moggallāna said, “I will tame him, venerable sir.” The Blessed One allowed it, saying, “Tame him, Moggallāna.” The elder abandoned that form and assumed the form of a huge royal nāga, and he surrounded Nandopananda fourteen times with his coils and raised his hood above the other’s hood, and he squeezed him against Sineru. The royal nāga produced smoke. [400] The elder said, “There is smoke not only in your body but also in mine,” and he produced smoke. The royal nāga’s smoke did not distress the elder, but the elder’s smoke distressed the royal nāga. Then the royal nāga produced flames. The elder said, “There is fire not only in your body but also in mine,” and he produced flames. The royal nāga’s fire did not distress the elder, but the elder’s fire distressed the royal nāga.

112. The royal nāga thought, “He has squeezed me against Sineru, and he has produced both smoke and flames.” Then he asked, “Sir, who are you?”—“I am Moggallāna, Nanda.”—“Venerable sir, resume your proper bhikkhu’s state.” The elder abandoned that form, and he went into his right ear and came out from his left ear; then he went into his left ear and came out from his right ear. Likewise he went into his right nostril and came out from his left nostril;then he went into his left nostril and came out from his right nostril. Then the royal nāga opened his mouth. The elder went inside it, and he walked up and down, east and west, inside his belly.

113. The Blessed One said, “Moggallāna, Moggallāna, beware; this is a mighty nāga.” The elder said, “Venerable sir, the four roads to power have been developed by me, repeatedly practiced, made the vehicle, made the basis, established, consolidated, and properly undertaken. I can tame not only Nandopananda, venerable sir, but a hundred, a thousand, a hundred thousand royal nāgas like Nandopananda.”

114. The royal nāga thought, “When he went in the first place I did not see him. But now when he comes out I shall catch him between my fangs and chew him up.” Then he said, “Venerable sir, come out. Do not keep troubling me by walking up and down inside my belly.” The elder came out and stood outside. The royal nāga recognized him, and blew a blast from his nose. The elder attained the fourth jhāna, and the blast failed to move even a single hair on his body. The other bhikkhus would, it seems, have been able to perform all the miracles up to now, but at this point they could not have attained with so rapid a response, which is why the Blessed One would not allow them to tame the royal nāga.

115. The royal nāga thought, “I have been unable to move even a single hair on this monk’s body with the blast from my nose. He is a mighty monk.” The elder abandoned that form, and having assumed the form of a supaṇṇa, he pursued the royal nāga demonstrating the supaṇṇa’s blast. [401] The royal nāga abandoned that form, and having assumed the form of a young brahman, he said, “Venerable sir, I go for refuge to you,” and he paid homage at the elder’s feet. The elder said, “The Master has come, Nanda; come, let us go to him.” So having tamed the royal nāga and deprived him of his poison, he went with him to the Blessed One’s presence.

116. The royal nāga paid homage to the Blessed One and said, “Venerable sir, I go for refuge to you.” The Blessed One said, “May you be happy, royal nāga.” Then he went, followed by the Community of Bhikkhus, to Anāthapiṇḍika’s house. Anāthapiṇḍika said, “Venerable sir, why have you come so late?”—“There was a battle between Moggallāna and Nandopananda.”—“Who won, venerable sir? Who was defeated?”—“Moggallāna won; Nanda was defeated.”

Anāthapiṇḍika said, “Venerable sir, let the Blessed One consent to my providing meals for seven days in a single series, and to my honouring the elder for seven days.” Then for seven days he accorded great honour to the five hundred bhikkhus with the Enlightened One at their head.

117. So it was with reference to this enlarged form created during this taming of Nandopananda that it was said: “When he makes his body big, does it not then become big, as in the case of the Elder Mahā Moggallāna?” (§105). Although this was said, the bhikkhus observed, “He enlarges only what is not clung to supported by what is clung to.” And only this is correct here.[19]

118. And when he has done this, he not only touches the moon and sun, but if he wishes, he makes a footstool [of them] and puts his feet on it, he makes a chair [of them] and sits on it, he makes a bed [of them] and lies on it, he makes a leaning-plank [of them] and leans on it. And as one does, so do others. For even when several hundred thousand bhikkhus do this and each one succeeds, still the motions of the moon and sun and their radiance remain the same. For just as when a thousand saucers are full of water and moon disks are seen in all the saucers, still the moon’s motion is normal and so is its radiance. And this miracle resembles that.

119. Even as far as the Brahmā-world: having made even the Brahmā-world the limit. He wields bodily mastery: herein, he wields self-mastery in the Brahmāworld by means of the body. The meaning of this should be understood according to the text.

Here is the text: “‘He wields bodily mastery even as far as the Brahmāworld’: if this possessor of supernormal power, having reached mental mastery, wants to go to the Brahmā-world, though far, he resolves upon nearness, ‘Let it be near.’ [402] It is near. Though near, he resolves upon farness, ‘Let it be far.’ It is far. Though many, he resolves upon few, ‘Let there be few.’ There are few. Though few, he resolves upon many, ‘Let there be many.’ There are many. With the divine eye he sees the [fine-material] visible form of that Brahmā. With the divine ear element he hears the voice of that Brahmā. With the knowledge of penetration of minds he understands that Brahmā’s mind. If this possessor of supernormal power, having reached mental mastery, wants to go to the Brahmāworld with a visible body, he converts his mind to accord with his body, he resolves his mind to accord with his body. Having converted his mind to accord with his body, resolved his mind to accord with his body, he arrives at blissful (easy) perception and light (quick) perception, and he goes to the Brahmāworld with a visible body. If this possessor of supernormal power, having reached mental mastery, wants to go to the Brahmā-world with an invisible body, he converts his body to accord with his mind, he resolves his body to accord with his mind. Having converted his body to accord with his mind, resolved his body to accord with his mind, he arrives at blissful (easy) perception and light (quick) perception, and he goes to the Brahmā-world with an invisible body. He creates a [fine-material] visible form before that Brahmā, mind-made with all its limbs, lacking no faculty. If that possessor of supernormal power walks up and down, the creation walks up and down there too. If that possessor of supernormal power stands … sits … lies down, the creation lies down there too. If that possessor of supernormal power produces smoke … produces flames … preaches Dhamma … asks a question … being asked a question, answers, the creation, being asked a question, answers there too. If that possessor of supernormal power stands with that Brahmā, converses, enters into communication with that Brahmā, the creation stands with that Brahmā there too, converses, enters into communication with that Brahmā there too. Whatever that possessor of supernormal power does, the creation does the same thing’” (Paṭis II 209).

120. Herein, though far, he resolves upon nearness: having emerged from the basic jhāna, he adverts to a far-off world of the gods or to the Brahmā-world thus, “Let it be near.” Having adverted and done the preliminary work, he attains again, and then resolves with knowledge: “Let it be near.” It becomes near. The same method of explanation applies to the other clauses too.