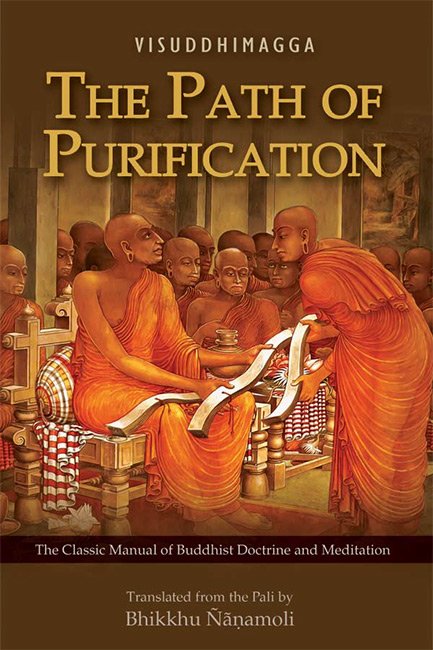

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes (9) Mindfulness of Breathing of the section Other Recollections as Meditation Subjects of Part 2 Concentration (Samādhi) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

(9) Mindfulness of Breathing

145. Now comes the description of the development of mindfulness of breathing as a meditation subject. It has been recommended by the Blessed One thus: “And, bhikkhus, this concentration through mindfulness of breathing, when developed and practiced much, is both peaceful and sublime, it is an unadulterated blissful abiding, and it banishes at once and stills evil unprofitable thoughts as soon as they arise” (S V 321; Vin III 70).

[Text]

It has been described by the Blessed One as having sixteen bases thus: “And how developed, bhikkhus, how practiced much, is concentration through mindfulness of breathing both peaceful and sublime, an unadulterated blissful abiding, banishing at once and stilling evil unprofitable thoughts as soon as they arise?

“Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, gone to the forest or to the root of a tree or to an empty place, sits down; having folded his legs crosswise, set his body erect, established mindfulness in front of him, [267] ever mindful he breathes in, mindful he breathes out.

“(i) Breathing in long, he knows: ‘I breathe in long;’ or breathing out long, he knows: ‘I breathe out long.’ (ii) Breathing in short, he knows: ‘I breathe in short;’ or breathing out short, he knows: ‘I breathe out short.’ (iii) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in experiencing the whole body;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out experiencing the whole body.’ (iv) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in tranquilizing the bodily formation;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation.’

“(v) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in experiencing happiness;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out experiencing happiness.’ (vi) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in experiencing bliss;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out experiencing bliss.’ (vii) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in experiencing the mental formation;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out experiencing the mental formation.’ (viii) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in tranquilizing the mental formation;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out tranquilizing the mental formation.’

“(ix) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in experiencing the [manner of] consciousness;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out experiencing the [manner of] consciousness.’ (x) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in gladdening the [manner of] consciousness;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out gladdening the [manner of] consciousness.’ (xi) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in concentrating the [manner of] consciousness;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out concentrating the [manner of] consciousness.’ (xii) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in liberating the [manner of] consciousness;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out liberating the [manner of] consciousness.’

“(xiii) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in contemplating impermanence;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out contemplating impermanence.’ (xiv) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in contemplating fading away;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out contemplating fading away.’ (xv) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in contemplating cessation;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out contemplating cessation.’ (xvi) He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in contemplating relinquishment;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out contemplating relinquishment’ (S V 321–22).

146. The description [of development] is complete in all respects, however, only if it is given in due course after a commentary on the text. So it is given here (§186) introduced by a commentary on the [first part of the] text.

[Word Commentary]

And how developed, bhikkhus, how practiced much, is concentration through mindfulness of breathing: here in the first place how is a question showing desire to explain in detail the development of concentration through mindfulness of breathing in its various forms. Developed, bhikkhus, … is concentration through mindfulness of breathing: this shows the thing that is being asked about out of desire to explain it in its various forms. How practiced much … as soon as they arise?: here too the same explanation applies.

147. Herein, developed means aroused or increased, concentration through mindfulness of breathing (lit. “breathing-mindfulness concentration”) is either concentration associated with mindfulness that discerns breathing, or it is concentration on mindfulness of breathing. Practiced much: practiced again and again.

148. Both peaceful and sublime (santo c’ eva paṇīto ca): it is peaceful in both ways and sublime in both ways; the two words should each be understood as governed by the word “both” (eva). What is meant? Unlike foulness, which as a meditation subject is peaceful and sublime only by penetration, but is neither (n’ eva) peaceful nor sublime in its object since its object [in the learning stage] is gross, and [after that] its object is repulsiveness—unlike that, this is not unpeaceful or unsublime in any way, but on the contrary it is peaceful, stilled and quiet both on account of the peacefulness of its object and on account of the peacefulness of that one of its factors called penetration. And it is sublime, something one cannot have enough of, both on account of the sublimeness of its object and on [268] account of the sublimeness of the aforesaid factor. Hence it is called “both peaceful and sublime.”

149. It is an unadulterated blissful abiding: it has no adulteration, thus it is unadulterated; it is unalloyed, unmixed, particular, special. Here it is not a question of peacefulness to be reached through preliminary work [as with the kasiṇas] or through access [as with foulness, for instance]. It is peaceful and sublime in its own individual essence too starting with the very first attention given to it. But some[1] say that it is “unadulterated” because it is unalloyed, possessed of nutritive value and sweet in its individual essence too. So it should be understood to be “unadulterated” and a “blissful abiding” since it leads to the obtaining of bodily and mental bliss with every moment of absorption.

150. As soon as they arise: whenever they are not suppressed. Evil: bad. Unprofitable (akusala) thoughts: thoughts produced by unskilfulness (akosalla). It banishes at once: it banishes, suppresses, at that very moment. Stills (vūpasameti): it thoroughly calms (suṭṭhu upasameti); or else, when eventually brought to fulfilment by the noble path, it cuts off, because of partaking of penetration;it tranquilizes, is what is meant.

151. In brief, however, the meaning here is this: “Bhikkhus, in what way, in what manner, by what system, is concentration through mindfulness of breathing developed, in what way is it practiced much, that it is both peaceful … as soon as they arise?”

152. He now said, “Here, bhikkhus,” etc., giving the meaning of that in detail.

Herein, here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu means: bhikkhus, in this dispensation a bhikkhu. For this word here signifies the [Buddha’s] dispensation as the prerequisite for a person to produce concentration through mindfulness of breathing in all its modes,[2] and it denies that such a state exists in any other dispensation. For this is said: “Bhikkhus, only here is there an ascetic, here a second ascetic, here a third ascetic, here a fourth ascetic; other dispensations are devoid of ascetics” (M I 63; A II 238).[3] That is why it was said above “in this dispensation a bhikkhu.”

153. Gone to the forest … or to an empty place: this signifies that he has found an abode favourable to the development of concentration through mindfulness of breathing. For this bhikkhu’s mind has long been dissipated among visible data, etc., as its object, and it does not want to mount the object of concentrationthrough-mindfulness-of-breathing; it runs off the track like a chariot harnessed to a wild ox.[4] Now, suppose a cowherd [269] wanted to tame a wild calf that had been reared on a wild cow’s milk, he would take it away from the cow and tie it up apart with a rope to a stout post dug into the ground; then the calf might dash to and fro, but being unable to get away, it would eventually sit down or lie down by the post. So too, when a bhikkhu wants to tame his own mind which has long been spoilt by being reared on visible data, etc., as object for its food and drink, he should take it away from visible data, etc., as object and bring it into the forest or to the root of a tree or to an empty place and tie it up there to the post of in-breaths and out-breaths with the rope of mindfulness. And so his mind may then dash to and fro when it no longer gets the objects it was formerly used to, but being unable to break the rope of mindfulness and get away, it sits down, lies down, by that object under the influence of access and absorption. Hence the Ancients said:

154. “Just as a man who tames a calf

Would tie it to a post, so here

Should his own mind by mindfulness

Be firmly to the object tied.”

This is how an abode is favourable to his development. Hence it was said above: “This signifies that he has found an abode favourable to the development of concentration through mindfulness of breathing.”

155. Or alternatively, this mindfulness of breathing as a meditation subject—which is foremost among the various meditation subjects of all Buddhas, [some] Paccekabuddhas and [some] Buddhas’ disciples as a basis for attaining distinction and abiding in bliss here and now—is not easy to develop without leaving the neighbourhood of villages, which resound with the noises of women, men, elephants, horses, etc., noise being a thorn to jhāna (see A V 135), whereas in the forest away from a village a meditator can at his ease set about discerning this meditation subject and achieve the fourth jhāna in mindfulness of breathing; and then, by making that same jhāna the basis for comprehension of formations [with insight] (XX.2f.), he can reach Arahantship, the highest fruit. That is why the Blessed One said “gone to the forest,” etc., in pointing out a favourable abode for him.

156. For the Blessed One is like a master of the art of building sites (see D I 9, 12; II 87). [270] As the master of the art of building sites surveys the proposed site for a town, thoroughly examines it, and then gives his directions, “Build the town here,” and when the town is safely finished, he receives great honour from the royal family, so the Blessed One examines an abode as to its suitability for the meditator, and he directs, “Devote yourself to the meditation subject here,” and later on, when the meditator has devoted himself to the meditation subject and has reached Arahantship and says, “The Blessed One is indeed fully enlightened,” the Blessed One receives great honour.

157. And this bhikkhu is compared to a leopard. For just as a great leopard king lurks in a grass wilderness or a jungle wilderness or a rock wilderness in the forest and seizes wild beasts—the wild buffalo, wild ox, boar, etc.—so too, the bhikkhu who devotes himself to his meditation subject in the forest, etc., should be understood to seize successively the paths of stream-entry, once-return, non-return, and Arahantship; and the noble fruitions as well. Hence the Ancients said:

“For as the leopard by his lurking [in the forest] seizes beasts

So also will this Buddhas’ son, with insight gifted, strenuous,

By his retreating to the forest seize the highest fruit of all” (Mil 369).

So the Blessed One said “gone to the forest,” etc., to point out a forest abode as a place likely to hasten his advancement.

158. Herein, gone to the forest is gone to any kind of forest possessing the bliss of seclusion among the kinds of forests characterized thus: “Having gone out beyond the boundary post, all that is forest” (Paṭis I 176; Vibh 251), and “A forest abode is five hundred bow lengths distant” (Vin IV 183). To the root of a tree: gone to the vicinity of a tree. To an empty place: gone to an empty, secluded space. And here he can be said to have gone to an “empty place” if he has gone to any of the remaining seven kinds of abode (resting place).[5] [271]

159. Having thus indicated an abode that is suitable to the three seasons, suitable to humour and temperament,[6] and favourable to the development of mindfulness of breathing, he then said sits down, etc., indicating a posture that is peaceful and tends neither to idleness nor to agitation. Then he said having folded his legs crosswise, etc., to show firmness in the sitting position, easy occurrence of the in-breaths and out-breaths, and the means for discerning the object.

160. Herein, crosswise is the sitting position with the thighs fully locked. Folded: having locked. Set his body erect: having placed the upper part of the body erect with the eighteen backbones resting end to end. For when he is seated like this, his skin, flesh and sinews are not twisted, and so the feelings that would arise moment by moment if they were twisted do not arise. That being so, his mind becomes unified, and the meditation subject, instead of collapsing, attains to growth and increase.

161. Established mindfulness in front of him (parimukhaṃ satiṃ upaṭṭhapetvā) = having placed (ṭhapayitvā) mindfulness (satiṃ) facing the meditation subject (kammaṭṭhānābhimukhaṃ). Or alternatively, the meaning can be treated here too according to the method of explanation given in the Paṭisambhidā, which is this: Pari has the sense of control (pariggaha), mukhaṃ (lit. mouth) has the sense of outlet (niyyāna), sati has the sense of establishment (upaṭṭhāna); that is why parimukhaṃ satiṃ (‘mindfulness as a controlled outlet’) is said” (Paṭis I 176). The meaning of it in brief is: Having made mindfulness the outlet (from opposition, forgetfulness being thereby] controlled.[7]

162. Ever mindful he breathes in, mindful he breathes out: having seated himself thus, having established mindfulness thus, the bhikkhu does not abandon that mindfulness; ever mindful he breathes in, mindful he breathes out; he is a mindful worker, is what is meant.

[Word Commentary Continued—First Tetrad]

163. (i) Now, breathing in long, etc., is said in order to show the different ways in which he is a mindful worker. For in the Paṭisambhidā, in the exposition of the clause, “Ever mindful he breathes in, mindful he breathes out,” this is said: “He is a mindful worker in thirty-two ways: (1) when he knows unification of mind and non-distraction by means of a long in-breath, mindfulness is established in him; owing to that mindfulness and that knowledge he is a mindful worker. (2) When he knows unification of mind and non-distraction by means of a long out-breath … (31) by means of breathing in contemplating relinquishment … (32) When he knows unification of mind and non-distraction by means of breathing out contemplating relinquishment, mindfulness is established in him; owing to that mindfulness and that knowledge he is a mindful worker” (Paṭis I 176).

164. Herein, breathing in long (assasanto) is producing a long in-breath. [272] “Assāsa is the wind issuing out; passāsa is the wind entering in” is said in the Vinaya Commentary. But in the Suttanta Commentaries it is given in the opposite sense. Herein, when any infant comes out from the mother’s womb, first the wind from within goes out and subsequently the wind from without enters in with fine dust, strikes the palate and is extinguished [with the infant’s sneezing]. This, firstly, is how assāsa and passāsa should be understood.

165. But their length and shortness should be understood by extent (addhāna). For just as water or sand that occupies an extent of space is called a “long water,” a “long sand,” a “short water,” a “short sand,” so in the case of elephants’ and snakes’ bodies the in-breaths and out-breaths regarded as particles[8] slowly fill the long extent, in other words, their persons, and slowly go out again. That is why they are called “long.” They rapidly fill a short extent, in other words, the person of a dog, a hare, etc., and rapidly go out again. That is why they are called “short.”

166. And in the case of human beings some breathe in and breathe out long, by extent of time, as elephants, snakes, etc., do, while others breathe in and breathe out short in that way as dogs, hares, etc., do. Of these, therefore, the breaths that travel over a long extent in entering in and going out are to be understood as long in time; and the breaths that travel over a little extent in entering in and going out, as short in time.

167. Now, this bhikkhu knows “I breathe in, I breathe out, long” while breathing in and breathing out long in nine ways. And the development of the foundation of mindfulness consisting in contemplation of the body should be understood to be perfected in one aspect in him who knows thus, according as it is said in the Paṭisambhidā:

168. “How, breathing in long, does he know: ‘I breathe in long,’ breathing out long, does he know: ‘I breathe out long?’ (1) He breathes in a long in-breath reckoned as an extent. (2) He breathes out a long out-breath reckoned as an extent. (3) He breathes in and breathes out long in-breaths and out-breaths reckoned as an extent. As he breathes in and breathes out long in-breaths and out-breaths reckoned as an extent, zeal arises.[9] (4) Through zeal he breathes in a long in-breath more subtle than before reckoned as an extent. (5) Through zeal he breathes out a long out-breath more subtle than before reckoned as an extent. (6) Through zeal he breathes in and breathes out long in-breaths and out-breaths more subtle than before reckoned as an extent. As, through zeal, he breathes in and breathes out long in-breaths and out-breaths more subtle than before reckoned as an extent, gladness arises. [273] (7) Through gladness he breathes in a long in-breath more subtle than before reckoned as an extent. (8) Through gladness he breathes out a long out-breath more subtle than before reckoned as an extent. (9) Through gladness he breathes in and breathes out long in-breaths and out-breaths more subtle than before reckoned as an extent. As, through gladness, he breathes in and breathes out long in-breaths and out-breaths more subtle than before reckoned as an extent, his mind turns away from the long inbreaths and out-breaths and equanimity is established.

“Long in-breaths and out-breaths in these nine ways are a body. The establishment (foundation)[10] is mindfulness. The contemplation is knowledge. The body is the establishment (foundation), but it is not the mindfulness. Mindfulness is both the establishment (foundation) and the mindfulness. By means of that mindfulness and that knowledge he contemplates that body. That is why ‘development of the foundation (establishment) of mindfulness consisting in contemplation of the body as a body’ (see D II 290) is said” (Paṭis I 177).

169. (ii) The same method of explanation applies also in the case of short breaths. But there is this difference. While in the former case “a long in-breath reckoned as an extent” is said, here “a short in-breath reckoned as a little [duration]” (Paṭis I 182) is given. So it must be construed as “short” as far as the phrase “That is why ‘development of the foundation (establishment) of mindfulness consisting in contemplation of the body as a body’ is said” (Paṭis I 183).

170. So it should be understood that it is when this bhikkhu knows in-breaths and out-breaths in these nine ways as “a [long] extent” and as “a little [duration]” that “breathing in long, he knows ‘I breathe in long;’ … breathing out short, he knows ‘I breathe out short’ is said of him. And when he knows thus:

“The long kind and the short as well,

The in-breath and the out-breath too,

Such then are the four kinds that happen

At the bhikkhu’s nose tip here.”

171. (iii) He trains thus: “I shall breathe in … I shall breathe out experiencing the whole body”: he trains thus: “I shall breathe in making known, making plain, the beginning, middle and end[11] of the entire in-breath body. I shall breathe out making known, making plain, the beginning, middle and end of the entire outbreath body,” thus he trains. Making them known, making them plain, in this way he both breathes in and breathes out with consciousness associated with knowledge. That is why it is said, “He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out …’”

172. To one bhikkhu the beginning of the in-breath body or the out-breath body, distributed in particles, [that is to say, regarded as successive arisings (see note 45)] is plain, but not the middle or the end; he is only able to discern the beginning and has difficulty with the middle and the end. To another the middle is plain, not the beginning or the end; he is only able to discern the middle and has difficulty with the beginning and the end. To another the end is plain, not the beginning or the middle; he is only able to discern the end [274] and has difficulty with the beginning and the middle. To yet another all stages are plain; he is able to discern them all and has no difficulty with any of them. Pointing out that one should be like the last-mentioned bhikkhu, he said: “He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out experiencing the whole body.’”

173. Herein, he trains: he strives, he endeavours in this way. Or else the restraint here in one such as this is training in the higher virtue, his consciousness is training in the higher consciousness, and his understanding is training in the higher understanding (see Paṭis I 184). So he trains in, repeats, develops, repeatedly practices, these three kinds of training, on that object, by means of that mindfulness, by means of that attention. This is how the meaning should be regarded here.

174. Herein, in the first part of the system (nos. i and ii)[12] he should only breathe in and breathe out and not do anything else at all, and it is only afterwards that he should apply himself to the arousing of knowledge, and so on. Consequently the present tense is used here in the text, “He knows: ‘I breathe in’ … he knows: ‘I breathe out.’” But the future tense in the passage beginning “I shall breathe in experiencing the whole body” should be understood as used in order to show that the aspect of arousing knowledge, etc., has to be undertaken from then on.

175. (iv) He trains thus: “I shall breathe in … shall breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation;” he trains thus: “I shall breathe in, shall breathe out tranquilizing, completely tranquilizing, stopping, stilling, the gross bodily formation[13]”.

176. And here both the gross and subtle state and also [progressive] tranquilizing should be understood. For previously, at the time when the bhikkhu has still not discerned [the meditation subject], his body and his mind are disturbed and so they are gross. And while the grossness of the body and the mind has still not subsided the in-breaths and out-breaths are gross. They get stronger; his nostrils become inadequate, and he keeps breathing in and out through his mouth. But they become quiet and still when his body and mind have been discerned. When they are still then the in-breaths and out-breaths occur so subtly that he has to investigate whether they exist or not.

177. Suppose a man stands still after running, or descending from a hill, or putting down a big load from his head, then his in-breaths and out-breaths are gross, his nostrils become inadequate, and he keeps on breathing in and out through his mouth. But when he has rid himself of his fatigue and has bathed and drunk [275] and put a wet cloth on his heart, and is lying in the cool shade, then his in-breaths and out-breaths eventually occur so subtly that he has to investigate whether they exist or not; so too, previously, at the time when the bhikkhu has still not discerned, … he has to investigate whether they exist or not.

178. Why is that? Because previously, at the time when he has still not discerned, there is no concern in him, no reaction, no attention, no reviewing, to the effect that “I am [progressively] tranquilizing each grosser bodily formation.” But when he has discerned, there is. So his bodily formation at the time when he has discerned is subtle in comparison with that at the time when he has not. Hence the Ancients said:

“The mind and body are disturbed,

And then in excess it occurs;

But when the body is undisturbed,

Then it with subtlety occurs.”

179. In discerning [the meditation subject the formation] is gross, and it is subtle [by comparison] in the first-jhāna access; also it is gross in that, and subtle [by comparison] in the first jhāna; in the first jhāna and second-jhāna access it is gross, and in the second jhāna subtle; in the second jhāna and third-jhāna access it is gross, and in the third jhāna subtle; in the third jhāna and fourth-jhāna access it is gross, and in the fourth jhāna it is so exceedingly subtle that it even reaches cessation. This is the opinion of the Dīgha and Saṃyutta reciters. But the Majjhima reciters have it that it is subtler in each access than in the jhāna below too in this way: In the first jhāna it is gross, and in the second-jhāna access it is subtle [by comparison, and so on]. It is, however, the opinion of all that the bodily formation occurring before the time of discerning becomes tranquilized at the time of discerning, and the bodily formation at the time of discerning becomes tranquilized in the first-jhāna access … and the bodily formation occurring in the fourth-jhāna access becomes tranquilized in the fourth jhāna. This is the method of explanation in the case of serenity.

180. But in the case of insight, the bodily formation occurring at the time of not discerning is gross, and in discerning the primary elements it is [by comparison] subtle; that also is gross, and in discerning derived materiality it is subtle; that also is gross, and in discerning all materiality it is subtle; that also is gross, and in discerning the immaterial it is subtle; that also is gross, and in discerning the material and immaterial it is subtle; that also is gross, and in discerning conditions it is subtle; that also is gross, and in seeing mentality-materiality with its conditions it is subtle; that also is gross, and in insight that has the characteristics [of impermanence, etc.,] as its object it is subtle; that also is gross in weak insight while in strong insight it is subtle.

Herein, the tranquilizing should be understood as [the relative tranquillity] of the subsequent compared with the previous. Thus should the gross and subtle state, and the [progressive] tranquilizing, be understood here. [276]

181. But the meaning of this is given in the Paṭisambhidā together with the objection and clarification thus:

“How is it that he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation? What are the bodily formations? Long inbreaths … out-breaths [experiencing the whole body] belong to the body; these things, being bound up with the body, are bodily formations;’ he trains in tranquilizing, stopping, stilling, those bodily formations.

“When there are such bodily formations whereby there is bending backwards, sideways in all directions, and forwards, and perturbation, vacillation, moving and shaking of the body, he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in tranquilizing the bodily formation;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation.’ When there are such bodily formations whereby there is no bending backwards, sideways in all directions, and forwards, and no perturbation, vacillation, moving and shaking of the body, quietly, subtly, he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in tranquilizing the bodily formation;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation.’

182. “[Objection:] So then, he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in tranquilizing the bodily formation;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation’: that being so, there is no production of awareness of wind, and there is no production of in-breaths and out-breaths, and there is no production of mindfulness of breathing, and there is no production of concentration through mindfulness of breathing, and consequently the wise neither enter into nor emerge from that attainment.

183. “[Clarification:] So then, he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in tranquilizing the bodily formation;’ he trains thus: ‘I shall breathe out tranquilizing the bodily formation’: that being so, there is production of awareness of wind, and there is production of in-breaths and out-breaths, and there is production of mindfulness of breathing, and there is production of concentration through mindfulness of breathing, and consequently the wise enter into and emerge from that attainment.

184. “Like what? Just as when a gong is struck. At first gross sounds occur and consciousness [occurs] because the sign of the gross sounds is well apprehended, well attended to, well observed; and when the gross sounds have ceased, then afterwards faint sounds occur and [consciousness occurs] because the sign of the faint sounds is well apprehended, well attended to, well observed; and when the faint sounds have ceased, then [277] afterwards consciousness occurs because it has the sign of the faint sounds as its object[14]—so too, at first gross in-breaths and out-breaths occur and [consciousness does not become distracted] because the sign of the gross in-breaths and out-breaths is well apprehended, well attended to, well observed; and when the gross in-breaths and out-breaths have ceased, then afterwards faint in-breaths and out-breaths occur and [consciousness does not become distracted] because the sign of the faint in-breaths and out-breaths is well apprehended, well attended to, well observed; and when the faint in-breaths and out-breaths have ceased, then afterwards consciousness does not become distracted because it has the sign of the faint in-breaths and out-breaths as its object.

“That being so, there is production of awareness of wind, and there is production of in-breaths and out-breaths, and there is production of mindfulness of breathing, and there is production of concentration through mindfulness of breathing, and consequently the wise enter into and emerge from that attainment. 185. “In-breaths and out-breaths tranquilizing the bodily formation are a body. The establishment (foundation) is mindfulness. The contemplation is knowledge. The body is the establishment (foundation), but it is not the mindfulness. Mindfulness is both the establishment (foundation) and the mindfulness. By means of that mindfulness and that knowledge he contemplates that body. That is why ‘development of the foundation (establishment) of mindfulness consisting in contemplation of the body as a body’ is said” (Paṭis I 184–186).

This, in the first place, is the consecutive word commentary here on the first tetrad, which deals with contemplation of the body.

[Method of Development]

186. The first tetrad is set forth as a meditation subject for a beginner;[15] but the other three tetrads are [respectively] set forth as the contemplations of feeling, of [the manner of] consciousness, and of mental objects, for one who has already attained jhāna in this tetrad. So if a clansman who is a beginner wants to develop this meditation subject, and through insight based on the fourth jhāna produced in breathing, to reach Arahantship together with the discriminations, he should first do all the work connected with the purification of virtue, etc., in the way already described, after which he should learn the meditation subject in five stages from a teacher of the kind already described.

187. Here are the five stages: learning, questioning, establishing, absorption, characteristic.

Herein, learning is learning the meditation subject. Questioning is questioning about the meditation subject. Establishing is establishing the meditation subject. Absorption [278] is the absorption of the meditation subject. Characteristic is the characteristic of the meditation subject; what is meant is that it is the ascertaining of the meditation subject’s individual essence thus: “This meditation subject has such a characteristic.”

188. Learning the meditation subject in the five stages in this way, he neither tires himself nor worries the teacher. So in giving this meditation subject consisting in mindfulness of breathing attention, he can live either with the teacher or elsewhere in an abode of the kind already described, learning the meditation subject in the five stages thus, getting a little expounded at a time and taking a long time over reciting it. He should sever the minor impediments. After finishing the work connected with the meal and getting rid of any dizziness due to the meal, he should seat himself comfortably. Then, making sure he is not confused about even a single word of what he has learned from the teacher, he should cheer his mind by recollecting the special qualities of the Three Jewels.

189. Here are the stages in giving attention to it: (1) counting, (2) connection, (3) touching, (4) fixing, (5) observing, (6) turning away, (7) purification, and (8) looking back on these.

Herein, counting is just counting, connection is carrying on, touching is the place touched [by the breaths], fixing is absorption, observing is insight, turning away is the path, purification is fruition, looking back on these is reviewing.

190. 1. Herein, this clansman who is a beginner should first give attention to this meditation subject by counting. And when counting, he should not stop short of five or go beyond ten or make any break in the series. By stopping short of five his thoughts get excited in the cramped space, like a herd of cattle shut in a cramped pen. By going beyond ten his thoughts take the number [rather than the breaths] for their support. By making a break in the series he wonders if the meditation subject has reached completion or not. So he should do his counting without those faults.

191. When counting, he should at first do it slowly [that is, late] as a grain measurer does. For a grain measurer, having filled his measure, says “One,” and empties it, and then refilling it, he goes on saying ‘”One, one” while removing any rubbish he may have noticed. And the same with “Two, two” and so on. So, taking the in-breath or the out-breath, whichever appears [most plainly], he should begin with “One, one” [279] and count up to “Ten, ten,” noting each as it occurs.

192. As he does his counting in this way, the in-breaths and out-breaths become evident to him as they enter in and issue out. Then he can leave off counting slowly (late), like a grain measurer, and he can count quickly [that is, early] as a cowherd does. For a skilled cowherd takes pebbles in his pocket and goes to the cow pen in the morning, whip in hand; sitting on the bar of the gate, prodding the cows in the back, he counts each one as it reaches the gate, saying “One, two,” dropping a pebble for each. And the cows of the herd, which have been spending the three watches of the night uncomfortably in the cramped space, come out quickly in parties, jostling each other as they escape. So he counts quickly (early) “Three, four, five” and so up to ten. In this way the in-breaths and out-breaths, which had already become evident to him while he counted them in the former way, now keep moving along quickly.

193. Then, knowing that they keep moving along quickly, not apprehending them either inside or outside [the body], but apprehending them just as they reach the [nostril] door, he can do his counting quickly (early): “One, two, three, four, five; one, two, three, four, five, six … seven … eight … nine … ten.” For as long as the meditation subject is connected with counting it is with the help of that very counting that the mind becomes unified, just as a boat in a swift current is steadied with the help of a rudder.

194. When he counts quickly, the meditation subject becomes apparent to him as an uninterrupted process. Then, knowing that it is proceeding uninterruptedly, he can count quickly (early) in the way just described, not discerning the wind either inside or outside [the body]. For by bringing his consciousness inside along with the incoming breath, it seems as if it were buffeted by the wind inside or filled with fat.[16] By taking his consciousness outside along with the outgoing breath, it gets distracted by the multiplicity of objects outside. However, his development is successful when he fixes his mindfulness on the place touched [by the breaths]. That is why it was said above: “He can count quickly (early) in the way just described, not discerning the wind either inside or outside.”

195. But how long is he to go on counting? Until, without counting, [280] mindfulness remains settled on the in-breaths and out-breaths as its object. For counting is simply a device for setting mindfulness on the in-breaths and outbreaths as object by cutting off the external dissipation of applied thoughts.

196. 2. Having given attention to it in this way by counting, he should now do so by connection. Connection is the uninterrupted following of the in-breaths and out-breaths with mindfulness after counting has been given up. And that is not by following after the beginning, the middle and the end.[17]

197. The navel is the beginning of the wind issuing out, the heart is its middle and the nose-tip is its end. The nose-tip is the beginning of the wind entering in, the heart is its middle and the navel is its end. And if he follows after that, his mind is distracted by disquiet and perturbation according as it is said: “When he goes in with mindfulness after the beginning, middle, and end of the inbreath, his mind being distracted internally, both his body and his mind are disquieted and perturbed and shaky. When he goes out with mindfulness after the beginning, middle and end of the out-breath, his mind being distracted externally, both his body and his mind are disquieted and perturbed and shaky” (Paṭis I 165).

3–4. So when he gives his attention to it by connection, he should do so not by the beginning, middle and end, but rather by touching and by fixing.

198. There is no attention to be given to it by touching separate from fixing as there is by counting separate from connection. But when he is counting the breaths in the place touched by each, he is giving attention to them by counting and touching. When he has given up counting and is connecting them by means of mindfulness in that same place and fixing consciousness by means of absorption, then he is said to be giving his attention to them by connection, touching and fixing. And the meaning of this may be understood through the similes of the man who cannot walk and the gatekeeper given in the commentaries, and through the simile of the saw given in the Paṭisambhidā.

199. Here is the simile of the man who cannot walk: Just as a man unable to walk, who is rocking a swing for the amusement of his children and their mother, sits at the foot of the swing post and sees both ends and the middle of the swing plank successively coming and going, [281] yet does not move from his place in order to see both ends and the middle, so too, when a bhikkhu places himself with mindfulness, as it were, at the foot of the post for anchoring [mindfulness] and rocks the swing of the in-breaths and out-breaths; he sits down with mindfulness on the sign at that same place, and follows with mindfulness the beginning, middle and end of the in-breaths and out-breaths at the place touched by them as they come and go; keeping his mind fixed there, he then sees them without moving from his place in order to see them. This is the simile of the man who cannot walk.

200. This is the simile of the gatekeeper: Just as a gatekeeper does not examine people inside and outside the town, asking, “Who are you? Where have you come from? Where are you going? What have you got in your hand?”—for those people are not his concern—but he does examine each man as he arrives at the gate, so too, the incoming breaths that have gone inside and the outgoing breaths that have gone outside are not this bhikkhu’s concern, but they are his concern each time they arrive at the [nostril] gate itself.

201. Then the simile of the saw should be understood from its beginning. For this is said:

“Sign, in-breath, out-breath, are not object

Of a single consciousness;

By one who knows not these three things

Development is not obtained.

“Sign, in-breath, out-breath, are not object

Of a single consciousness;

By one who does know these three things

Development can be obtained.”

202. “How is it that these three things are not the object of a single consciousness, that they are nevertheless not unknown, that the mind does not become distracted, that he manifests effort, carries out a task, and achieves an effect?

“Suppose there were a tree trunk placed on a level piece of ground, and a man cut it with a saw. The man’s mindfulness is established by the saw’s teeth where they touch the tree trunk, without his giving attention to the saw’s teeth as they approach and recede, though they are not unknown to him as they do so; and he manifests effort, carries out a task, and achieves an effect. As the tree trunk placed on the level piece of ground, so the sign for the anchoring of mindfulness.

As the saw’s teeth, so the in-breaths and out-breaths. As the man’s mindfulness, established by the saw’s teeth where they touch the tree trunk, without his giving attention to the saw’s teeth as they approach and recede, though they are not unknown to him as they do so, and so he manifests effort, carries out a task, and achieves an effect, [282] so too, the bhikkhu sits, having established mindfulness at the nose tip or on the upper lip, without giving attention to the in-breaths and out-breaths as they approach and recede, though they are not unknown to him as they do so, and he manifests effort, carries out a task, and achieves an effect.

203. “‘Effort’: what is the effort? The body and the mind of one who is energetic become wieldy—this is the effort. What is the task? Imperfections come to be abandoned in one who is energetic, and his applied thoughts are stilled—this is the task. What is the effect? Fetters come to be abandoned in one who is energetic, and his inherent tendencies come to be done away with—this is the effect.

“So these three things are not the object of a single consciousness, and they are nevertheless not unknown, and the mind does not become distracted, and he manifests effort, carries out a task, and achieves an effect.

“Whose mindfulness of breathing in

And out is perfect, well developed,

And gradually brought to growth

According as the Buddha taught,

’Tis he illuminates the world

Just like the full moon free from cloud”[18]

This is the simile of the saw. But here it is precisely his not giving attention [to the breaths] as [yet to] come and [already] gone[19] that should be understood as the purpose.

204. When someone gives his attention to this meditation subject, sometimes it is not long before the sign arises in him, and then the fixing, in other words, absorption adorned with the rest of the jhāna factors, is achieved.

205. After someone has given his attention to counting, then just as when a body that is disturbed sits down on a bed or chair, the bed or chair sags down and creaks and the cover gets rumpled, but when a body that is not disturbed sits down, the bed or chair neither sags down nor creaks, the cover does not get rumpled, and it is as though filled with cotton wool—why? because a body that is not disturbed is light—so too, after he has given his attention to counting, when the bodily disturbance has been stilled by the gradual cessation of gross in-breaths and out-breaths, then both the body and the mind become light: the physical body is as though it were ready to leap up into the air. [283]

206. When his gross in-breaths and out breaths have ceased, his consciousness occurs with the sign of the subtle in-breaths and out-breaths as its object. And when that has ceased, it goes on occurring with the successively subtler signs as its object. How?

207. Suppose a man stuck a bronze bell with a big iron bar and at once a loud sound arose, his consciousness would occur with the gross sound as its object;then, when the gross sound had ceased, it would occur afterwards with the sign of the subtle sound as its object; and when that had ceased, it would go on occurring with the sign of the successively subtler sounds as its object. This is how it should be understood. And this is given in detail in the passage beginning, “Just as when a metal gong is struck” (§184).

208. For while other meditation subjects become clearer at each higher stage, this one does not: in fact, as he goes on developing it, it becomes more subtle for him at each higher stage, and it even comes to the point at which it is no longer manifest.

However, when it becomes unmanifest in this way, the bhikkhu should not get up from his seat, shake out his leather mat, and go away. What should be done? He should not get up with the idea “Shall I ask the teacher?” or “Is my meditation subject lost?”; for by going away, and so disturbing his posture, the meditation subject has to be started anew. So he should go on sitting as he was and [temporarily] substitute the place [normally touched for the actual breaths as the object of contemplation].[20]

209. These are the means for doing it. The bhikkhu should recognize the unmanifest state of the meditation subject and consider thus: “Where do these in-breaths and out-breaths exist? Where do they not? In whom do they exist? In whom not?” Then, as he considers thus, he finds that they do not exist in one inside the mother’s womb, or in those drowned in water, or likewise in unconscious beings,[21] or in the dead, or in those attained to the fourth jhāna, or in those born into a fine-material or immaterial existence, or in those attained to cessation [of perception and feeling]. So he should apostrophize himself thus: “You with all your wisdom are certainly not inside a mother’s womb or drowned in water or in the unconscious existence or dead or attained to the fourth jhāna or born into the fine-material or immaterial existence or attained to cessation. Those in-breaths and out-breath are actually existent in you, only you are not able to discern them because your understanding is dull.” Then, fixing his mind on the place normally touched [by the breaths], he should proceed to give his attention to that.

210. These in-breaths and out-breaths occur striking the tip of the nose in a long-nosed man [284] and the upper lip in a short-nosed man. So he should fix the sign thus: “This is the place where they strike.” This was why the Blessed One said: “Bhikkhus, I do not say of one who is forgetful, who is not fully aware, [that he practices] development of mindfulness of breathing” (M III 84).

211. Although any meditation subject, no matter what, is successful only in one who is mindful and fully aware, yet any meditation subject other than this one gets more evident as he goes on giving it his attention. But this mindfulness of breathing is difficult, difficult to develop, a field in which only the minds of Buddhas, Paccekabuddhas, and Buddhas’ sons are at home. It is no trivial matter, nor can it be cultivated by trivial persons. In proportion as continued attention is given to it, it becomes more peaceful and more subtle. So strong mindfulness and understanding are necessary here.

212. Just as when doing needlework on a piece of fine cloth a fine needle is needed, and a still finer instrument for boring the needle’s eye, so too, when developing this meditation subject, which resembles fine cloth, both the mindfulness, which is the counterpart of the needle, and the understanding associated with it, which is the counterpart of the instrument for boring the needle’s eye, need to be strong. A bhikkhu must have the necessary mindfulness and understanding and must look for the in-breaths and out-breaths nowhere else than the place normally touched by them.

213. Suppose a ploughman, after doing some ploughing, sent his oxen free to graze and sat down to rest in the shade, then his oxen would soon go into the forest. Now, a skilled ploughman who wants to catch them and yoke them again does not wander through the forest following their tracks, but rather he takes his rope and goad and goes straight to the drinking place where they meet, and he sits or lies there. Then after the oxen have wandered about for a part of the day, they come to the drinking place where they meet and they bathe and drink, and when he sees that they have come out and are standing about, he secures them with the rope, and prodding them with the goad, he brings them back, yokes them, and goes on with his ploughing. So too, the bhikkhu should not look for the in-breaths and outbreaths anywhere else than the place normally touched by them. And he should take the rope of mindfulness and the goad of understanding, and fixing his mind on the place normally touched by them, he should go on giving his attention to that. [285] For as he gives his attention in this way they reappear after no long time, as the oxen did at the drinking place where they met. So he can secure them with the rope of mindfulness, and yoking them in that same place and prodding them with the goad of understanding, he can keep on applying himself to the meditation subject.

214. When he does so in this way, the sign[22] soon appears to him. But it is not the same for all; on the contrary, some say that when it appears it does so to certain people producing a light touch like cotton or silk-cotton or a draught.

215. But this is the exposition given in the commentaries: It appears to some like a star or a cluster of gems or a cluster of pearls, to others with a rough touch like that of silk-cotton seeds or a peg made of heartwood, to others like a long braid string or a wreath of flowers or a puff of smoke, to others like a stretchedout cobweb or a film of cloud or a lotus flower or a chariot wheel or the moon’s disk or the sun’s disk.

216. In fact this resembles an occasion when a number of bhikkhus are sitting together reciting a suttanta. When a bhikkhu asks, “What does this sutta appear like to you?” one says, “It appears to me like a great mountain torrent,” another “To me it is like a line of forest trees,” another “To me it is like a spreading fruit tree giving cool shade.” For the one sutta appears to them differently because of the difference in their perception. Similarly this single meditation subject appears differently because of difference in perception.[23] It is born of perception, its source is perception, it is produced by perception. Therefore it should be understood that when it appears differently it is because of difference in perception.

217. And here, the consciousness that has in-breath as its object is one, the consciousness that has out-breath as its object is another, and the consciousness that has the sign as its object is another. For the meditation subject reaches neither absorption nor even access in one who has not got these three things [clear]. But it reaches access and also absorption in one who has got these three things [clear]. For this is said:

“Sign, in-breath, out-breath, are not object

Of a single consciousness;

By one who knows not these three things

Development is not obtained.Sign, in-breath, out-breath, are not object

Of a single consciousness;

By one who does know these three things

Development can be obtained” (Paṭis I 170). [286]

218. And when the sign has appeared in this way, the bhikkhu should go to the teacher and tell him, “Venerable sir, such and such has appeared to me.” But [say the Dīgha reciters] the teacher should say neither “This is the sign” nor “This is not the sign”; after saying “It happens like this, friend,” he should tell him, “Go on giving it attention again and again;” for if he were told “It is the sign,” he might [become complacent and] stop short at that (see M I 193f.), and if he were told “It is not the sign,” he might get discouraged and give up; so he should encourage him to keep giving it his attention without saying either. So the Dīgha reciters say, firstly. But the Majjhima reciters say that he should be told, “This is the sign, friend. Well done. Keep giving attention to it again and again.”

219. Then he should fix his mind on that same sign; and so from now on, his development proceeds by way of fixing. For the Ancients said this:

“Fixing his mind upon the sign

And putting away[24] extraneous aspects,

The clever man anchors his mind

Upon the breathings in and out.”

220. So as soon as the sign appears, his hindrances are suppressed, his defilements subside, his mindfulness is established, and his consciousness is concentrated in access concentration.

221. Then he should not give attention to the sign as to its colour, or review it as to its [specific] characteristic. He should guard it as carefully as a king’s chief queen guards the child in her womb due to become a Wheel-turning Monarch,[25] or as a farmer guards the ripening crops; and he should avoid the seven unsuitable things beginning with the unsuitable abode and cultivate the seven suitable things. Then, guarding it thus, he should make it grow and improve with repeated attention, and he should practice the tenfold skill in absorption (IV.42) and bring about evenness of energy (IV.66).

222. As he strives thus, fourfold and fivefold jhāna is achieved by him on that same sign in the same way as described under the earth kasiṇa.

5–8. (See §189) However, when a bhikkhu has achieved the fourfold and fivefold jhāna and wants to reach purity by developing the meditation subject through observing and through turning away, he should make that jhāna familiar by attaining mastery in it in the five ways (IV.131), and then embark upon insight by defining mentality-materiality. How?

223. On emerging from the attainment, [287] he sees that the in-breaths and out-breaths have the physical body and the mind as their origin;and that just as, when a blacksmith’s bellows are being blown, the wind moves owing to the bag and to the man’s appropriate effort, so too, in-breaths and out-breaths are due to the body and the mind.

Next, he defines the in-breaths and out-breaths and the body as “materiality,” and the consciousness and the states associated with the consciousness as “the immaterial [mind].” This is in brief (cf. M-a I 249); but the details will be explained later in the defining of mentality-materiality (XVIII.3f.).

224. Having defined mentality-materiality in this way, he seeks its condition. With search he finds it, and so overcomes his doubts about the way of mentalitymateriality’s occurrence in the three divisions of time (Ch. XIX).

His doubts being overcome, he attributes the three characteristics [beginning with that of suffering to mentality and materiality], comprehending [them] by groups (XX.2f.); he abandons the ten imperfections of insight beginning with illumination, which arise in the first stages of the contemplation of rise and fall (XX.105f.), and he defines as “the path” the knowledge of the way that is free from these imperfections (XX.126f.).

He reaches contemplation of dissolution by abandoning [attention to] arising. When all formations have appeared as terror owing to the contemplation of their incessant dissolution, he becomes dispassionate towards them (Ch. XXI), his greed for them fades away, and he is liberated from them (Ch. XXII).

After he has [thus] reached the four noble paths in due succession and has become established in the fruition of Arahantship, he at last attains to the nineteen kinds of reviewing knowledge (XXII.19f.), and he becomes fit to receive the highest gifts from the world with its deities.

225. At this point his development of concentration through mindfulness of breathing, beginning with counting and ending with looking back (§189) is completed.

This is the commentary on the first tetrad in all aspects.

[Word Commentary Continued—Second Tetrad]

226. Now, since there is no separate method for developing the meditation subject in the case of the other tetrads, their meaning therefore needs only to be understood according to the word commentary.

(v) He trains thus: “I shall breathe in … shall breathe out experiencing happiness,” that is, making happiness known, making it plain. Herein, the happiness is experienced in two ways: (a) with the object, and (b) with non-confusion.[26]

227. (a) How is the happiness experienced with the object? He attains the two jhānas in which happiness is present. At the time when he has actually entered upon them the happiness is experienced with the object owing to the obtaining of the jhāna, because of the experiencing of the object. (b) How with nonconfusion? When, after entering upon and emerging from one of the two jhānas accompanied by happiness, [288] he comprehends with insight that happiness associated with the jhāna as liable to destruction and to fall, then at the actual time of the insight the happiness is experienced with non-confusion owing to the penetration of its characteristics [of impermanence, and so on].

228. For this is said in the Paṭisambhidā: “When he knows unification of mind and non-distraction through long in-breaths, mindfulness is established in him. By means of that mindfulness and that knowledge that happiness is experienced. When he knows unification of mind and non-distraction through long outbreaths … through short in-breaths … through short out-breaths … through inbreaths … out-breaths experiencing the whole body … through in-breaths … out-breaths tranquilizing the bodily formation, mindfulness is established in him. By means of that mindfulness and that knowledge that happiness is experienced.

“It is experienced by him when he adverts, when he knows, sees, reviews, steadies his mind, resolves with faith, exerts energy, establishes mindfulness, concentrates his mind, understands with understanding, directly knows what is to be directly known, fully understands what is to be fully understood, abandons what is to be abandoned, develops what is to be developed, realizes what is to be realized. It is in this way that that happiness is experienced” (Paṭis I 187).

229. (vi–viii) The remaining [three] clauses should be understood in the same way as to meaning; but there is this difference here. The experiencing of bliss must be understood to be through three jhānas, and that of the mental formation through four. The mental formation consists of the two aggregates of feeling and perception. And in the case of the clause, experiencing bliss, it is said in the Paṭisambhidā in order to show the plane of insight here [as well]: “‘Bliss’: there are two kinds of bliss, bodily bliss and mental bliss” (Paṭis I 188). Tranquilizing the mental formation: tranquilizing the gross mental formation; stopping it, is the meaning. And this should be understood in detail in the same way as given under the bodily formation (see §§176–85).

230. Here, moreover, in the “happiness” clause feeling [which is actually being contemplated in this tetrad] is stated under the heading of “happiness” [which is a formation] but in the “bliss” clause feeling is stated in its own form. In the two “mental-formation” clauses the feeling is that [necessarily] associated with perception because of the words, “Perception and feeling belong to the mind, these things being bound up with the mind are mental formations” (Paṭis I 188). [289]

So this tetrad should be understood to deal with contemplation of feeling.

[Word Commentary Continued—Third Tetrad]

231. (ix) In the third tetrad the experiencing of the [manner of] consciousness must be understood to be through four jhānas.

(x) Gladdening the [manner of] consciousness: he trains thus: “Making the mind glad, instilling gladness into it, cheering it, rejoicing it, I shall breathe in, shall breathe out.” Herein, there is gladdening in two ways, through concentration and through insight.

How through concentration? He attains the two jhānas in which happiness is present. At the time when he has actually entered upon them he inspires the mind with gladness, instils gladness into it, by means of the happiness associated with the jhāna. How through insight? After entering upon and emerging from one of the two jhānas accompanied by happiness, he comprehends with insight that happiness associated with the jhāna as liable to destruction and to fall; thus at the actual time of insight he inspires the mind with gladness, instils gladness into it, by making the happiness associated with the jhāna the object. It is of one progressing in this way that the words, “He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out gladdening the [manner of] consciousness,’” are said.

232. (xi) Concentrating (samādahaṃ) the [manner of] consciousness: evenly (samaṃ) placing (ādahanto) the mind, evenly putting it on its object by means of the first jhāna and so on. Or alternatively, when, having entered upon those jhānas and emerged from them, he comprehends with insight the consciousness associated with the jhāna as liable to destruction and to fall, then at the actual time of insight momentary unification of the mind[27] arises through the penetration of the characteristics [of impermanence, and so on]. Thus the words, “He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out concentrating the [manner of] consciousness,’” are said also of one who evenly places the mind, evenly puts it on its object by means of the momentary unification of the mind arisen thus.

233. (xii) Liberating the [manner of] consciousness: he both breathes in and breathes out delivering, liberating, the mind from the hindrances by means of the first jhāna, from applied and sustained thought by means of the second, from happiness by means of the third, from pleasure and pain by means of the fourth. Or alternatively, when, having entered upon those jhānas and emerged from them, he comprehends with insight the consciousness associated with the jhāna as liable to destruction and to fall, then at the actual time of insight he delivers, liberates, the mind from the perception of permanence by means of the contemplation of impermanence, from the perception of pleasure by means of the contemplation of pain, from the perception of self by means of the contemplation of not self, from delight by means of the contemplation of dispassion, from greed by means of the contemplation of fading away, from arousing by means of the contemplation of cessation, from grasping by means of the contemplation of relinquishment. Hence it is said: [290] “He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out liberating the [manner of] consciousness.[28]’” So this tetrad should be understood to deal with contemplation of mind. [Word Commentary Continued—Fourth Tetrad]

234. (xiii) But in the fourth tetrad, as to contemplating impermanence, here firstly, the impermanent should be understood, and impermanence, and the contemplation of impermanence, and one contemplating impermanence.

Herein, the five aggregates are the impermanent. Why? Because their essence is rise and fall and change. Impermanence is the rise and fall and change in those same aggregates, or it is their non-existence after having been; the meaning is, it is the breakup of produced aggregates through their momentary dissolution since they do not remain in the same mode. Contemplation of impermanence is contemplation of materiality, etc., as “impermanent” in virtue of that impermanence. One contemplating impermanence possesses that contemplation. So it is when one such as this is breathing in and breathing out that it can be understood of him: “He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out contemplating impermanence.’”[29]

235. (xiv) Contemplating fading away: there are two kinds of fading away, that is, fading away as destruction, and absolute fading away.[30] Herein, “fading away as destruction” is the momentary dissolution of formations. “Absolute fading away” is Nibbāna. Contemplation of fading away is insight and it is the path, which occurs as the seeing of these two. It is when he possesses this twofold contemplation that it can be understood of him: “He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out contemplating fading away.’”

(xv) The same method of explanation applies to the clause, contemplating cessation.

236. (xvi) Contemplating relinquishment: relinquishment is of two kinds too, that is to say, relinquishment as giving up, and relinquishment as entering into. Relinquishment itself as [a way of] contemplation is “contemplation of relinquishment.” For insight is called both “relinquishment as giving up” and “relinquishment as entering into” since [firstly], through substitution of opposite qualities, it gives up defilements with their aggregate-producing kamma formations, and [secondly], through seeing the wretchedness of what is formed, it also enters into Nibbāna by inclining towards Nibbāna, which is the opposite of the formed (XI.18). Also the path is called both “relinquishment as giving up” and “relinquishment as entering into” since it gives up defilements with their aggregate-producing kamma-formations by cutting them off, and it enters into Nibbāna by making it its object. Also both [insight and path knowledge] are called contemplation (anupassanā) because of their re-seeing successively (anu anu passanā) each preceding kind of knowledge.[31] [291] It is when he possesses this twofold contemplation that it can be understood of him: “He trains thus: ‘I shall breathe in … shall breathe out contemplating relinquishment.’”

237. This tetrad deals only with pure insight while the previous three deal with serenity and insight. This is how the development of mindfulness of breathing with its sixteen bases in four tetrads should be understood.

[Conclusion]

This mindfulness of breathing with its sixteen bases thus is of great fruit, of great benefit.

238. Its great beneficialness should be understood here as peacefulness both because of the words, “And, bhikkhus, this concentration through mindfulness of breathing, when developed and much practiced, is both peaceful and sublime” (S V 321), etc., and because of its ability to cut off applied thoughts; for it is because it is peaceful, sublime, and an unadulterated blissful abiding that it cuts off the mind’s running hither and thither with applied thoughts obstructive to concentration, and keeps the mind only on the breaths as object. Hence it is said: “Mindfulness of breathing should be developed in order to cut off applied thoughts” (A IV 353).

239. Also its great beneficialness should be understood as the root condition for the perfecting of clear vision and deliverance; for this has been said by the Blessed One: “Bhikkhus, mindfulness of breathing, when developed and much practiced, perfects the four foundations of mindfulness. The four foundations of mindfulness, when developed and much practiced, perfect the seven enlightenment factors. The seven enlightenment factors, when developed and much practiced, perfect clear vision and deliverance” (M III 82).

240. Again its great beneficialness should be understood to reside in the fact that it causes the final in-breaths and out-breaths to be known; for this is said by the Blessed One: “Rāhula, when mindfulness of breathing is thus developed, thus practiced much, the final in-breaths and out-breaths, too, are known as they cease, not unknown” (M I 425f.).

241. Herein, there are three kinds of [breaths that are] final because of cessation, that is to say, final in becoming, final in jhāna, and final in death. For, among the various kinds of becoming (existence), in-breaths and out-breaths occur in the sensual-sphere becoming, not in the fine-material and immaterial kinds of becoming. That is why there are final ones in becoming. In the jhānas they occur in the first three but not in the fourth. That is why there are final ones in jhāna. Those that arise along with the sixteenth consciousness preceding the death consciousness [292] cease together with the death consciousness. They are called “final in death.” It is these last that are meant here by “final.”

242. When a bhikkhu has devoted himself to this meditation subject, it seems, if he adverts, at the moment of arising of the sixteenth consciousness before the death consciousness, to their arising, then their arising is evident to him; if he adverts to their presence, then their presence is evident to him;if he adverts to their dissolution, then their dissolution is evident to him;and it is so because he has thoroughly discerned in-breaths and out-breaths as object.

243. When a bhikkhu has attained Arahantship by developing some other meditation subject than this one, he may be able to define his life term or not. But when he has reached Arahantship by developing this mindfulness of breathing with its sixteen bases, he can always define his life term. He knows, “My vital formations will continue now for so long and no more.” Automatically he performs all the functions of attending to the body, dressing and robing, etc., after which he closes his eyes, like the Elder Tissa who lived at the Koṭapabbata Monastery, like the Elder Mahā Tissa who lived at the Mahā Karañjiya Monastery, like the Elder Tissa the alms-food eater in the kingdom of Devaputta, like the elders who were brothers and lived at the Cittalapabbata monastery.

244. Here is one story as an illustration. After reciting the Pātimokkha, it seems, on the Uposatha day of the full moon, one of the two elders who were brothers went to his own dwelling place surrounded by the Community of Bhikkhus. As he stood on the walk looking at the moonlight he calculated his own vital formations, and he said to the Community of Bhikkhus, “In what way have you seen bhikkhus attaining Nibbāna up till now?” Some answered, “Till now we have seen them attain Nibbāna sitting in their seats.” Others answered, “We have seen them sitting cross-legged in the air.” The elder said, “I shall now show you one attaining Nibbāna while walking.” He then drew a line on the walk, saying, “I shall go from this end of the walk to the other end and return; when I reach this line I shall attain Nibbāna.” So saying, he stepped on to the walk and went to the far end. On his return he attained Nibbāna in the same moment in which he stepped on the line. [293]

So let a man, if he is wise,

Untiringly devote his days

To mindfulness of breathing, which

Rewards him always in these ways.

This is the section dealing with mindfulness of breathing in the detailed explanation.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

“‘Some’ is said with reference to the inmates of the Uttara (Northern) monastery [in Anurādhapura]” (Vism-mhṭ 256).

[2]:

“The words ‘in all its aspects’ refer to the sixteen bases; for these are only found in total in this dispensation. When outsiders know mindfulness of breathing they only know the first four modes” (Vism-mhṭ 257).

[3]:

“‘The ascetic’ is a stream-enterer, the ‘second ascetic’ is a once-returner, the ‘third ascetic’ is a non-returner, the ‘fourth ascetic’ is an Arahant” (M-a II 4).

[5]:

The nine kinds of abode (resting place) are the forest and the root of a tree already mentioned, and a rock, a hill cleft, a mountain cave, a charnel ground, a jungle thicket, an open space, a heap of straw (M I 181).

[6]:

“In the hot season the forest is favourable, in the cold season the root of a tree, in the rainy season an empty place. For one of phlegmatic humour, phlegmatic by nature, the forest is favourable, for one of bilious humour the root of a tree, for one of windy humour an empty place. For one of deluded temperament the forest, for one of hating temperament the root of a tree, for one of greedy temperament an empty place” (Vism-mhṭ 258).

[7]:

The amplification is from Vism-mhṭ 258.

[8]:

“‘Regarded as particles’: as a number of groups (kalāpa)” (Vism-mhṭ 259). This conception of the occurrence of breaths is based on the theory of motion as “successive arisings in adjacent locations” (desantaruppatti); see note 54 below. For “groups” see XX.2f.

[9]:

“‘Zeal arises’: additional zeal, which is profitable and has the characteristic of desire to act, arises due to the satisfaction obtained when the meditation has brought progressive improvement. ‘More subtle than before’: more subtle than before the already-described zeal arose; for the breaths occur more subtly owing to the meditation’s influence in tranquilizing the body’s distress and disturbance. ‘Gladness arises’: fresh happiness arises of the kinds classed as minor, etc., which is the gladness that accompanies the consciousness occupied with the meditation and is due to the fact that the peacefulness of the object increases with the growing subtlety of the breaths and to the fact that the meditation subject keeps to its course. ‘The mind turns away’: the mind turns away from the breaths, which have reached the point at which their manifestation needs investigating (see §177) owing to their gradually increasing subtlety. But some say (see Paṭis-a Ce, p. 351): ‘It is when the in-breaths and outbreaths have reached a subtler state owing to the influence of the meditation and the counterpart sign; for when that has arisen, the mind turns away from the normal breaths.’ ‘Equanimity is established’: when concentration, classed as access and absorption, has arisen in that counterpart sign, then, since there is no need for further interest to achieve jhāna, onlooking (equanimity) ensues, which is specific neutrality” (Vism-mhṭ 260).

[10]:

“‘In these nine ways’: that occur in the nine ways just described. ‘Long in-breaths and out-breaths are a body’: the in-breaths and out-breaths, which exist as particles though they have the aspect of length, constitute a ‘body’ in the sense of a mass. And here the sign that arises with the breaths as its support is also called ‘in-breath and out-breath.’ (cf. e.g. §206) ‘The establishment (foundation) is mindfulness’: mindfulness is called ‘establishment (foundation)—(upaṭṭhāna)’ since it approaches (upagantvā) the object and remains (tiṭṭhati) there. ‘The contemplation is knowledge’: contemplation of the sign by means of serenity, and contemplation of mentality-materiality by defining with insight the in-breaths and out-breaths and the body, which is their support, as materiality, and the consciousness and the states associated with it as the immaterial (mentality), are knowledge, in other words, awareness of what is actually there (has actually become). ‘The body is the establishment (foundation)’: there is that body, and mindfulness approaches it by making it its object and remains there, thus it is called ‘establishment.’ And the words ‘the body is the establishment’ include the other (the mental) kind of body too since the above-mentioned comprehension by insight is needed here too. ‘But it is not the mindfulness’: that body is not called ‘mindfulness’ [though it is called ‘the establishment’]. ‘Mindfulness is both the establishment (foundation) and the mindfulness,’ being so both in the sense of remembering (sarana) and in the sense of establishing (upatiṭṭhana). ‘By means of that mindfulness’: by means of that mindfulness already mentioned. ‘And that knowledge’: and the knowledge already mentioned. ‘That body’: that in-breath-and-out-breath body and that material body which is its support. ‘He contemplates (anupassati)’: he keeps reseeing (anu anu passati) with jhāna knowledge and with insight knowledge. ‘That is why “Development of the foundation (establishment) of mindfulness consisting in contemplation of the body as a body” is said’: in virtue of that contemplation this is said to be development of the foundation (establishment) of mindfulness consisting in contemplation of the body as a body of the kind already stated. What is meant is this: the contemplation of the body as an in-breath-and-out-breath body as stated and of the physical body that is its [material] support, which is not contemplation of permanence, etc., in a body whose individual essence is impermanent, etc.—like the contemplation of a waterless mirage as water—but which is rather contemplation of its essence as impermanent, painful, not-self, and foul, according as is appropriate, or alternatively, which is contemplation of it as a mere body only, by not contemplating it as containing anything that can be apprehended as ‘I’ or ‘mine’ or ‘woman’ or ‘man’—all this is ‘contemplation of the body.’ The mindfulness associated with that contemplation of the body, which mindfulness is itself the establishment, is the ‘establishment.’ The development, the increase, of that is the ‘development of the foundation (establishment) of mindfulness consisting in contemplation of the body.’” (Vism-mhṭ 261)

The compound satipaṭṭhāna is derived by the Paṭisambhidā from sati (mindfulness) and upaṭṭhāna (establishment—Paṭis I 182), but in the Commentaries the resolution into sati and paṭṭhāna (foundation) is preferred. (M-a I 237–38) In the 118th Sutta of the Majjhima Nikāya the first tetrad is called development of the first foundation of mindfulness, or contemplation of the body. (MN 10; DN 22) The object of the Paṭisambhidā passage quoted is to demonstrate this.

[11]:

The beginning, middle and end are described in §197, and the way they should be treated is given in §199–201. What is meant is that the meditator should know what they are and be aware of them without his mindfulness leaving the tip of the nose to follow after the breaths inside the body or outside it, speculating on what becomes of them.

[12]: