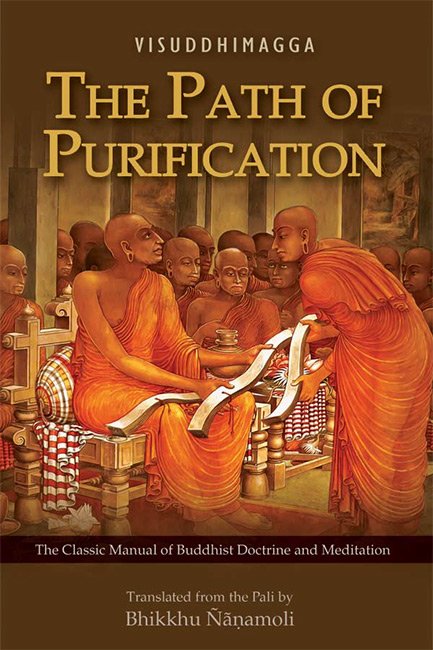

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes B1. Development of Concentration in Detail: (Continued) of the section Taking a Meditation Subject (Kammaṭṭhāna-gahaṇa-niddesa) of Part 2 Concentration (Samādhi) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

B1. Development of Concentration in Detail: (Continued)

57. Approach the good friend, the giver of a meditation subject (§28): meditation subjects are of two kinds, that is, generally useful meditation subjects and special meditation subjects. Herein, loving-kindness towards the Community of Bhikkhus, etc., and also mindfulness of death are what are called generally useful meditation subjects. Some say perception of foulness, too.

58. When a bhikkhu takes up a meditation subject, he should first develop loving-kindness towards the Community of Bhikkhus within the boundary,[1] limiting it at first [to “all bhikkhus in this monastery”], in this way: “May they be happy and free from affliction.” Then he should develop it towards all deities within the boundary. Then towards all the principal people in the village that is his alms resort; then to [all human beings there and to] all living beings dependent on the human beings. With loving-kindness towards the Community of Bhikkhus he produces kindliness in his co-residents; then they are easy for him to live with. With loving-kindness towards the deities within the boundary he is protected by kindly deities with lawful protection. [98] With lovingkindness towards the principal people in the village that is his alms resort his requisites are protected by well-disposed principal people with lawful protection. With loving-kindness to all human beings there he goes about without incurring their dislike since they trust him. With loving-kindness to all living beings he can wander unhindered everywhere.

With mindfulness of death, thinking, “I have got to die,” he gives up improper search (see S II 194; M-a I 115), and with a growing sense of urgency he comes to live without attachment. When his mind is familiar with the perception of foulness, then even divine objects do not tempt his mind to greed.

59. So these are called “generally useful” and they are “called meditation subjects” since they are needed[2] generally and desirable owing to their great helpfulness and since they are subjects for the meditation work intended.

60. What is called a “special meditation subject” is that one from among the forty meditation subjects that is suitable to a man’s own temperament. It is “special” (pārihāriya) because he must carry it (pariharitabbattā) constantly about with him, and because it is the proximate cause for each higher stage of development.

So it is the one who gives this twofold meditation subject that is called the giver of a meditation subject.

61. The good friend is one who possesses such special qualities as these:

He is revered and dearly loved,

And one who speaks and suffers speech;

The speech he utters is profound,

He does not urge without a reason (A IV 32) and so on.

He is wholly solicitous of welfare and partial to progress.

62. Because of the words beginning, “Ānanda, it is owing to my being a good friend to them that living beings subject to birth are freed from birth” (S I 88), it is only the Fully Enlightened One who possesses all the aspects of the good friend. Since that is so, while he is available only a meditation subject taken in the Blessed One’s presence is well taken.

But after his final attainment of Nibbāna, it is proper to take it from anyone of the eighty great disciples still living. When they are no more available, one who wants to take a particular meditation subject should take it from someone with cankers destroyed, who has, by means of that particular meditation subject, produced the fourfold and fivefold jhāna, and has reached the destruction of cankers by augmenting insight that had that jhāna as its proximate cause.

63. But how then, does someone with cankers destroyed declare himself thus: “I am one whose cankers are destroyed?” Why not? He declares himself when he knows that his instructions will be carried out. Did not the Elder Assagutta [99] spread out his leather mat in the air and sitting cross-legged on it explain a meditation subject to a bhikkhu who was starting his meditation subject, because he knew that that bhikkhu was one who would carry out his instructions for the meditation subject?

64. So if someone with cankers destroyed is available, that is good. If not, then one should take it from a non-returner, a once-returner, a stream-enterer, an ordinary man who has obtained jhāna, one who knows three Piṭakas, one who knows two Piṭakas, one who knows one Piṭaka, in descending order [according as available]. If not even one who knows one Piṭaka is available, then it should be taken from one who is familiar with one Collection together with its commentary and one who is himself conscientious. For a teacher such as this, who knows the texts, guards the heritage, and protects the tradition, will follow the teachers’ opinion rather than his own. Hence the Ancient Elders said three times, “One who is conscientious will guard it.”

65. Now, those beginning with one whose cankers are destroyed, mentioned above, will describe only the path they have themselves reached. But with a learned man, his instructions and his answers to questions are purified by his having approached such and such teachers, and so he will explain a meditation subject showing a broad track, like a big elephant going through a stretch of jungle, and he will select suttas and reasons from here and there, adding [explanations of] what is suitable and unsuitable. So a meditation subject should be taken by approaching the good friend such as this, the giver of a meditation subject, and by doing all the duties to him.

66. If he is available in the same monastery, it is good. If not, one should go to where he lives.

When [a bhikkhu] goes to him, he should not do so with feet washed and anointed, wearing sandals, with an umbrella, surrounded by pupils, and bringing oil tube, honey, molasses, etc.; he should do so fulfilling the duties of a bhikkhu setting out on a journey, carrying his bowl and robes himself, doing all the duties in each monastery on the way, with few belongings, and living in the greatest effacement. When entering that monastery, he should do so [expecting nothing, and even provided] with a tooth-stick that he has had made allowable on the way [according to the rules]. And he should not enter some other room, thinking, “I shall go to the teacher after resting awhile and after washing and anointing my feet, and so on.”

67. Why? If there are bhikkhus there who are hostile to the teacher, they might ask him the reason for his coming and speak dispraise of the teacher, saying, “You are done for if you go to him”; [100] they might make him regret his coming and turn him back. So he should ask for the teacher’s dwelling and go straight there.

68. If the teacher is junior, he should not consent to the teacher’s receiving his bowl and robe, and so on. If the teacher is senior, then he should go and pay homage to him and remain standing. When told, “Put down the bowl and robe, friend,” he may put them down. When told, “Have some water to drink,” he can drink if he wants to. When told, “You may wash your feet,” he should not do so at once, for if the water has been brought by the teacher himself, it would be improper. But when told “Wash, friend, it was not brought by me, it was brought by others,” then he can wash his feet, sitting in a screened place out of sight of the teacher, or in the open to one side of the dwelling.

69. If the teacher brings an oil tube, he should get up and take it carefully with both hands. If he did not take it, it might make the teacher wonder, “Does this bhikkhu resent sharing so soon?” but having taken it, he should not anoint his feet at once. For if it were oil for anointing the teacher’s limbs, it would not be proper. So he should first anoint his head, then his shoulders, etc.;but when told, “This is meant for all the limbs, friend, anoint your feet,” he should put a little on his head and then anoint his feet. Then he should give it back, saying when the teacher takes it, “May I return this oil tube, venerable sir?”

70. He should not say, “Explain a meditation subject to me, venerable sir” on the very day he arrives. But starting from the next day, he can, if the teacher has a habitual attendant, ask his permission to do the duties. If he does not allow it when asked, they can be done when the opportunity offers. When he does them, three tooth-sticks should be brought, a small, a medium and a big one, and two kinds of mouth-washing water and bathing water, that is, hot and cold, should be set out. Whichever of these the teacher uses for three days should then be brought regularly. If the teacher uses either kind indiscriminately, he can bring whatever is available.

71. Why so many words? All should be done as prescribed by the Blessed One in the Khandhakas as the right duties in the passage beginning: “Bhikkhus, a pupil should perform the duties to the teacher [101] rightly. Herein, this is the right performance of duties. He should rise early; removing his sandals and arranging his robe on one shoulder, he should give the tooth-sticks and the mouth-washing water, and he should prepare the seat. If there is rice gruel, he should wash the dish and bring the rice gruel” (Vin I 61).

72. To please the teacher by perfection in the duties he should pay homage in the evening, and he should leave when dismissed with the words, “You may go.” When the teacher asks him, “Why have you come?” he can explain the reason for his coming. If he does not ask but agrees to the duties being done, then after ten days or a fortnight have gone by he should make an opportunity by staying back one day at the time of his dismissal, and announcing the reason for his coming;or he should go at an unaccustomed time, and when asked, “What have you come for?” he can announce it.

73. If the teacher says, “Come in the morning,” he should do so. But if his stomach burns with a bile affliction at that hour, or if his food does not get digested owing to sluggish digestive heat, or if some other ailment afflicts him, he should let it be known, and proposing a time that suits himself, he should come at that time. For if a meditation subject is expounded at an inconvenient time, one cannot give attention.

This is the detailed explanation of the words “approach the good friend, the giver of a meditation subject.”

74. Now, as to the words, one that suits his temperament (§28): there are six kinds of temperament, that is, greedy temperament, hating temperament, deluded temperament, faithful temperament, intelligent temperament, and speculative temperament. Some would have fourteen, taking these six single ones together with the four made up of the three double combinations and one triple combination with the greed triad and likewise with the faith triad. But if this classification is admitted, there are many more kinds of temperament possible by combining greed, etc., with faith, etc.; therefore the kinds of temperament should be understood briefly as only six. As to meaning the temperaments are one, that is to say, personal nature, idiosyncrasy. According to [102] these there are only six types of persons, that is, one of greedy temperament, one of hating temperament, one of deluded temperament, one of faithful temperament, one of intelligent temperament, and one of speculative temperament.

75. Herein, one of faithful temperament is parallel to one of greedy temperament because faith is strong when profitable [kamma] occurs in one of greedy temperament, owing to its special qualities being near to those of greed. For, in an unprofitable way, greed is affectionate and not over-austere, and so, in a profitable way, is faith. Greed seeks out sense desires as object, while faith seeks out the special qualities of virtue and so on. And greed does not give up what is harmful, while faith does not give up what is beneficial.

76. One of intelligent temperament is parallel to one of hating temperament because understanding is strong when profitable [kamma] occurs in one of hating temperament, owing to its special qualities being near to those of hate. For, in an unprofitable way, hate is disaffected and does not hold to its object, and so, in a profitable way, is understanding. Hate seeks out only unreal faults, while understanding seeks out only real faults. And hate occurs in the mode of condemning living beings, while understanding occurs in the mode of condemning formations.

77. One of speculative temperament is parallel to one of deluded temperament because obstructive applied thoughts arise often in one of deluded temperament who is striving to arouse unarisen profitable states, owing to their special qualities being near to those of delusion. For just as delusion is restless owing to perplexity, so are applied thoughts that are due to thinking over various aspects. And just as delusion vacillates owing to superficiality, so do applied thoughts that are due to facile conjecturing.

78. Others say that there are three more kinds of temperament with craving, pride, and views. Herein craving is simply greed; and pride[3] is associated with that, so neither of them exceeds greed. And since views have their source in delusion, the temperament of views falls within the deluded temperament.

79. What is the source of these temperaments? And how is it to be known that such a person is of greedy temperament, that such a person is of one of those beginning with hating temperament? What suits one of what kind of temperament?

80. Herein, as some say,[4] the first three kinds of temperament to begin with have their source in previous habit; and they have their source in elements and humours. Apparently one of greedy temperament has formerly had plenty of desirable tasks and gratifying work to do, or has reappeared here after dying in a heaven. And one of hating temperament has formerly had plenty of stabbing and torturing and brutal work to do or has reappeared here after dying in one of the hells or the nāga (serpent) existences. And one [103] of deluded temperament has formerly drunk a lot of intoxicants and neglected learning and questioning, or has reappeared here after dying in the animal existence. It is in this way that they have their source in previous habit, they say.

81. Then a person is of deluded temperament because two elements are prominent, that is to say, the earth element and the water element. He is of hating temperament because the other two elements are prominent. But he is of greedy temperament because all four are equal. And as regards the humours, one of greedy temperament has phlegm in excess and one of deluded temperament has wind in excess. Or one of deluded temperament has phlegm in excess and one of greedy temperament has wind in excess. So they have their source in the elements and the humours, they say.

82. [Now, it can rightly be objected that] not all of those who have had plenty of desirable tasks and gratifying work to do, and who have reappeared here after dying in a heaven, are of greedy temperament, or the others respectively of hating and deluded temperament; and there is no such law of prominence of elements (see XIV.43f.) as that asserted; and only the pair, greed and delusion, are given in the law of humours, and even that subsequently contradicts itself; and no source for even one among those beginning with one of faithful temperament is given. Consequently this definition is indecisive.

83. The following is the exposition according to the opinion of the teachers of the commentaries; or this is said in the “explanation of prominence”: “The fact that these beings have prominence of greed, prominence of hate, prominence of delusion, is governed by previous root-cause.

“For when in one man, at the moment of his accumulating [rebirth-producing] kamma, greed is strong and non-greed is weak, non-hate and non-delusion are strong and hate and delusion are weak, then his weak non-greed is unable to prevail over his greed, but his non-hate and non-delusion being strong are able to prevail over his hate and delusion. That is why, on being reborn through rebirth-linking given by that kamma, he has greed, is good-natured and unangry, and possesses understanding with knowledge like a lightning flash.

84. “When, at the moment of another’s accumulating kamma, greed and hate are strong and non-greed and non-hate weak, and non-delusion is strong and delusion weak, then in the way already stated he has both greed and hate but possesses understanding with knowledge like a lightning flash, like the Elder Datta-Abhaya.

“When, at the moment of his accumulating kamma, greed, non-hate and delusion are strong and the others are weak, then in the way already stated he both has greed and is dull but is good-tempered[5] and unangry, like the Elder Bahula. “Likewise when, at the moment of his accumulating kamma, the three, namely, greed, hate and delusion are strong and non-greed, etc., are weak, then in the way already stated he has both greed and hate and is deluded. [104]

85. “When, at the moment of his accumulating kamma, non-greed, hate and delusion are strong and the others are weak, then in the way already stated he has little defilement and is unshakable even on seeing a heavenly object, but he has hate and is slow in understanding.

“When, at the moment of his accumulating kamma, non-greed, non-hate and non-delusion are strong and the rest weak, then in the way already stated he has no greed and no hate, and is good-tempered but slow in understanding.

“Likewise when, at the moment of his accumulating kamma, non-greed, hate and non-delusion are strong and the rest weak, then in the way already stated he both has no greed and possesses understanding but has hate and is irascible.

“Likewise when, at the moment of his accumulating kamma, the three, that is, non-hate, non-greed, and non-delusion, are strong and greed, etc., are weak, then in the way already stated he has no greed and no hate and possesses understanding, like the Elder Mahā-Saṅgharakkhita.”

86. One who, as it is said here, “has greed” is one of greedy temperament; one who “has hate” and one who “is dull” are respectively of hating temperament and deluded temperament. One who “possesses understanding” is one of intelligent temperament. One who “has no greed” and one who “has no hate” are of faithful temperament because they are naturally trustful. Or just as one who is reborn through kamma accompanied by non-delusion is of intelligent temperament, so one who is reborn through kamma accompanied by strong faith is of faithful temperament, one who is reborn through kamma accompanied by thoughts of sense desire is of speculative temperament, and one who is reborn through kamma accompanied by mixed greed, etc., is of mixed temperament. So it is the kamma productive of rebirth-linking and accompanied by someone among the things beginning with greed that should be understood as the source of the temperaments.

87. But it was asked, and how is it to be known that “This person is of greedy temperament?” (§79), and so on. This is explained as follows:

By the posture, by the action,

By eating, seeing, and so on,

By the kind of states occurring,

May temperament be recognized.

88. Herein, by the posture: when one of greedy temperament is walking in his usual manner, he walks carefully, puts his foot down slowly, puts it down evenly, lifts it up evenly, and his step is springy.[6]

One of hating temperament walks as though he were digging with the points of his feet, puts his foot down quickly, lifts it up quickly, and his step is dragged along.

One of deluded temperament walks with a perplexed gait, puts his foot down hesitantly, lifts it up hesitantly, [105] and his step is pressed down suddenly.

And this is said in the account of the origin of the Māgandiya Sutta:

The step of one of greedy nature will be springy;

The step of one of hating nature, dragged along;

Deluded, he will suddenly press down his step;

And one without defilement has a step like this.[7]

89. The stance of one of greedy temperament is confident and graceful. That of one of hating temperament is rigid. That of one of deluded temperament is muddled, likewise in sitting. And one of greedy temperament spreads his bed unhurriedly, lies down slowly, composing his limbs, and he sleeps in a confident manner. When woken, instead of getting up quickly, he gives his answer slowly as though doubtful. One of hating temperament spreads his bed hastily anyhow; with his body flung down he sleeps with a scowl. When woken, he gets up quickly and answers as though annoyed. One of deluded temperament spreads his bed all awry and sleeps mostly face downwards with his body sprawling. When woken, he gets up slowly, saying, “Hum.”

90. Since those of faithful temperament, etc., are parallel to those of greedy temperament, etc., their postures are therefore like those described above.

This firstly is how the temperaments may be recognized by the posture.

91. By the action: also in the acts of sweeping, etc., one of greedy temperament grasps the broom well, and he sweeps cleanly and evenly without hurrying or scattering the sand, as if he were strewing sinduvāra flowers. One of hating temperament grasps the broom tightly, and he sweeps uncleanly and unevenly with a harsh noise, hurriedly throwing up the sand on each side. One of deluded temperament grasps the broom loosely, and he sweeps neither cleanly nor evenly, mixing the sand up and turning it over.

92. As with sweeping, so too with any action such as washing and dyeing robes, and so on. One of greedy temperament acts skilfully, gently, evenly and carefully. One of hating temperament acts tensely, stiffly and unevenly. One of deluded temperament acts unskilfully as if muddled, unevenly and indecisively. [106]

Also one of greedy temperament wears his robe neither too tightly nor too loosely, confidently and level all round. One of hating temperament wears it too tight and not level all round. One of deluded temperament wears it loosely and in a muddled way.

Those of faithful temperament, etc., should be understood in the same way as those just described, since they are parallel.

This is how the temperaments may be recognized by the actions.

93. By eating: One of greedy temperament likes eating rich sweet food. When eating, he makes a round lump not too big and eats unhurriedly, savouring the various tastes. He enjoys getting something good. One of hating temperament likes eating rough sour food. When eating he makes a lump that fills his mouth, and he eats hurriedly without savouring the taste. He is aggrieved when he gets something not good. One of deluded temperament has no settled choice. When eating, he makes a small un-rounded lump, and as he eats he drops bits into his dish, smearing his face, with his mind astray, thinking of this and that.

Also those of faithful temperament, etc., should be understood in the same way as those just described since they are parallel.

This is how the temperament may be recognized by eating.

94. And by seeing and so on: when one of greedy temperament sees even a slightly pleasing visible object, he looks long as if surprised, he seizes on trivial virtues, discounts genuine faults, and when departing, he does so with regret as if unwilling to leave. When one of hating temperament sees even a slightly unpleasing visible object, he avoids looking long as if he were tired, he picks out trivial faults, discounts genuine virtues, and when departing, he does so without regret as if anxious to leave. When one of deluded temperament sees any sort of visible object, he copies what others do: if he hears others criticizing, he criticizes; if he hears others praising, he praises; but actually he feels equanimity in himself—the equanimity of unknowing. So too with sounds, and so on.

And those of faithful temperament, etc., should be understood in the same way as those just described since they are parallel.

This is how the temperaments may be recognized by seeing and so on.

95. By the kind of states occurring: in one of greedy temperament there is frequent occurrence of such states as deceit, fraud, pride, evilness of wishes, greatness of wishes, discontent, foppery and personal vanity.[8] [107] In one of hating temperament there is frequent occurrence of such states as anger, enmity, disparaging, domineering, envy and avarice. In one of deluded temperament there is frequent occurrence of such states as stiffness, torpor, agitation, worry, uncertainty, and holding on tenaciously with refusal to relinquish.

In one of faithful temperament there is frequent occurrence of such states as free generosity, desire to see Noble Ones, desire to hear the Good Dhamma, great gladness, ingenuousness, honesty, and trust in things that inspire trust. In one of intelligent temperament there is frequent occurrence of such states as readiness to be spoken to, possession of good friends, knowledge of the right amount in eating, mindfulness and full awareness, devotion to wakefulness, a sense of urgency about things that should inspire a sense of urgency, and wisely directed endeavour. In one of speculative temperament there is frequent occurrence of such states as talkativeness, sociability, boredom with devotion to the profitable, failure to finish undertakings, smoking by night and flaming by day (see M I 144—that is to say, hatching plans at night and putting them into effect by day), and mental running hither and thither (see Ud 37).

This is how the temperaments may be recognized by the kind of states occurring.

96. However, these directions for recognizing the temperaments have not been handed down in their entirety in either the texts or the commentaries; they are only expressed according to the opinion of the teachers and cannot therefore be treated as authentic. For even those of hating temperament can exhibit postures, etc., ascribed to the greedy temperament when they try diligently. And postures, etc., never arise with distinct characteristics in a person of mixed temperament. Only such directions for recognizing temperament as are given in the commentaries should be treated as authentic; for this is said: “A teacher who has acquired penetration of minds will know the temperament and will explain a meditation subject accordingly; one who has not should question the pupil.” So it is by penetration of minds or by questioning the person, that it can be known whether he is one of greedy temperament or one of those beginning with hating temperament.

97. What suits one of what kind of temperament? (§79). A suitable lodging for one of greedy temperament has an unwashed sill and stands level with the ground, and it can be either an overhanging [rock with an] unprepared [drip-ledge] (see Ch. II, note 15), a grass hut, or a leaf house, etc. It ought to be spattered with dirt, full of bats,[9] dilapidated, too high or too low, in bleak surroundings, threatened [by lions, tigers, etc.,] with a muddy, uneven path, [108] where even the bed and chair are full of bugs. And it should be ugly and unsightly, exciting loathing as soon as looked at. Suitable inner and outer garments are those that have torn-off edges with threads hanging down all round like a “net cake,”[10] harsh to the touch like hemp, soiled, heavy and hard to wear. And the right kind of bowl for him is an ugly clay bowl disfigured by stoppings and joints, or a heavy and misshapen iron bowl as unappetizing as a skull. The right kind of road for him on which to wander for alms is disagreeable, with no village near, and uneven. The right kind of village for him in which to wander for alms is where people wander about as if oblivious of him, where, as he is about to leave without getting alms even from a single family, people call him into the sitting hall, saying, “Come, venerable sir,” and give him gruel and rice, but do so as casually as if they were putting a cow in a pen. Suitable people to serve him are slaves or workmen who are unsightly, ill-favoured, with dirty clothes, ill-smelling and disgusting, who serve him his gruel and rice as if they were throwing it rudely at him. The right kind of gruel and rice and hard food is poor, unsightly, made up of millet, kudusaka, broken rice, etc., stale buttermilk, sour gruel, curry of old vegetables, or anything at all that is merely for filling the stomach. The right kind of posture for him is either standing or walking. The object of his contemplation should be any of the colour kasiṇas, beginning with the blue, whose colour is not pure. This is what suits one of greedy temperament.

98. A suitable resting place for one of hating temperament is not too high or too low, provided with shade and water, with well-proportioned walls, posts and steps, with well-prepared frieze work and lattice work, brightened with various kinds of painting, with an even, smooth, soft floor, adorned with festoons of flowers and a canopy of many-coloured cloth like a Brahmā-god’s divine palace, with bed and chair covered with well-spread clean pretty covers, smelling sweetly of flowers, and perfumes and scents set about for homely comfort, which makes one happy and glad at the mere sight of it.

99. The right kind of road to his lodging is free from any sort of danger, traverses clean, even ground, and has been properly prepared. [109] And here it is best that the lodging’s furnishings are not too many in order to avoid hiding-places for insects, bugs, snakes and rats: even a single bed and chair only. The right kind of inner and outer garments for him are of any superior stuff such as China cloth, Somāra cloth, silk, fine cotton, fine linen, of either single or double thickness, quite light, and well dyed, quite pure in colour to befit an ascetic. The right kind of bowl is made of iron, as well shaped as a water bubble, as polished as a gem, spotless, and of quite pure colour to befit an ascetic. The right kind of road on which to wander for alms is free from dangers, level, agreeable, with the village neither too far nor too near. The right kind of village in which to wander for alms is where people, thinking, “Now our lord is coming,” prepare a seat in a sprinkled, swept place, and going out to meet him, take his bowl, lead him to the house, seat him on a prepared seat and serve him carefully with their own hands.

100. Suitable people to serve him are handsome, pleasing, well bathed, well anointed, scented[11] with the perfume of incense and the smell of flowers, adorned with apparel made of variously-dyed clean pretty cloth, who do their work carefully. The right kind of gruel, rice, and hard food has colour, smell and taste, possesses nutritive essence, and is inviting, superior in every way, and enough for his wants. The right kind of posture for him is lying down or sitting. The object of his contemplation should be anyone of the colour kasiṇas, beginning with the blue, whose colour is quite pure. This is what suits one of hating temperament.

101. The right lodging for one of deluded temperament has a view and is not shut in, where the four quarters are visible to him as he sits there. As to the postures, walking is right. The right kind of object for his contemplation is not small, that is to say, the size of a winnowing basket or the size of a saucer; for his mind becomes more confused in a confined space; so the right kind is an amply large kasiṇa. The rest is as stated for one of hating temperament. This is what suits one of deluded temperament.

102. For one of faithful temperament all the directions given for one of hating temperament are suitable. As to the object of his contemplation, one of the recollections is right as well.

For one of intelligent temperament there is nothing unsuitable as far as concerns the lodging and so on.

For one of speculative temperament an open lodging with a view, [110] where gardens, groves and ponds, pleasant prospects, panoramas of villages, towns and countryside, and the blue gleam of mountains, are visible to him as he sits there, is not right; for that is a condition for the running hither and thither of applied thought. So he should live in a lodging such as a deep cavern screened by woods like the Overhanging Rock of the Elephant’s Belly (Hatthikucchipabbhāra), or Mahinda’s Cave. Also an ample-sized object of contemplation is not suitable for him; for one like that is a condition for the running hither and thither of applied thought. A small one is right. The rest is as stated for one of greedy temperament. This is what suits one of speculative temperament.

These are the details, with definition of the kind, source, recognition, and what is suitable, as regards the various temperaments handed down here with the words “that suits his own temperament” (§60).

103. However, the meditation subject that is suitable to the temperament has not been cleared up in all its aspects yet. This will become clear automatically when those in the following list are treated in detail.

Now, it was said above, “and he should apprehend from among the forty meditation subjects one that suits his own temperament” (§60). Here the exposition of the meditation subject should be first understood in these ten ways: (1) as to enumeration, (2) as to which bring only access and which absorption, (3) at to the kinds of jhāna, (4) as to surmounting, (5) as to extension and non-extension, (6) as to object, (7) as to plane, (8) as to apprehending, (9) as to condition, (10) as to suitability to temperament.

104. 1. Herein, as to enumeration: it was said above, “from among the forty meditation subjects” (§28). Herein, the forty meditation subjects are these:

ten kasiṇas (totalities),

ten kinds of foulness,

ten recollections,

four divine abidings,

four immaterial states,

one perception,

one defining.

105. Herein, the ten kasiṇas are these: earth kasiṇa, water kasiṇa, fire kasiṇa, air kasiṇa, blue kasiṇa, yellow kasiṇa, red kasiṇa, white kasiṇa, light kasiṇa, and limited-space kasiṇa.[12]

The ten kinds of foulness are these: the bloated, the livid, the festering, the cutup, the gnawed, the scattered, the hacked and scattered, the bleeding, the worm-infested, and a skeleton.[13]

The ten kinds of recollection are these: recollection of the Buddha (the Enlightened One), recollection of the Dhamma (the Law), recollection of the Sangha (the Community), recollection of virtue, recollection of generosity, recollection of deities, recollection (or mindfulness) of death, mindfulness occupied with the body, mindfulness of breathing, and recollection of peace. [111]

The four divine abidings are these: loving-kindness, compassion, gladness, and equanimity.

The four immaterial states are these: the base consisting of boundless space, the base consisting of boundless consciousness, the base consisting of nothingness, and the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception.

The one perception is the perception of repulsiveness in nutriment.

The one defining is the defining of the four elements.

This is how the exposition should be understood “as to enumeration.”

106. 2 As to which bring access only and which absorption: the eight recollections—excepting mindfulness occupied with the body and mindfulness of breathing—the perception of repulsiveness in nutriment, and the defining of the four elements, are ten meditation subjects that bring access only. The others bring absorption. This is “as to which bring access only and which absorption.”

107. 3. As to the kind of jhāna: among those that bring absorption, the ten kasiṇas together with mindfulness of breathing bring all four jhānas. The ten kinds of foulness together with mindfulness occupied with the body bring the first jhāna.

The first three divine abidings bring three jhānas. The fourth divine abiding and the four immaterial states bring the fourth jhāna. This is “as to the kind of jhāna.”

108. 4. As to surmounting: there are two kinds of surmounting, that is to say, surmounting of factors and surmounting of object. Herein, there is surmounting of factors in the case of all meditation subjects that bring three and four jhānas because the second jhāna, etc., have to be reached in those same objects by surmounting the jhāna factors of applied thought and sustained thought, and so on. Likewise in the case of the fourth divine abiding; for that has to be reached by surmounting joy in the same object as that of loving-kindness, and so on. But in the case of the four immaterial states there is surmounting of the object; for the base consisting of boundless space has to be reached by surmounting one or other of the first nine kasiṇas, and the base consisting of boundless consciousness, etc., have respectively to be reached by surmounting space, and so on. With the rest there is no surmounting. This is “as to surmounting.”

109. 5. As to extension and non-extension: only the ten kasiṇas among these forty meditation subjects need be extended. For it is within just so much space as one is intent upon with the kasiṇa that one can hear sounds with the divine ear element, see visible objects with the divine eye, and know the minds of other beings with the mind.

110. Mindfulness occupied with the body and the ten kinds of foulness need not be extended. Why? Because they have a definite location and because there is no benefit in it. The definiteness of their location will become clear in explaining the method of development (VIII.83–138 and VI.40, 41, 79). If the latter are extended, it is only a quantity of corpses that is extended [112] and there is no benefit. And this is said in answer to the question of Sopāka: “Perception of visible forms is quite clear, Blessed One, perception of bones is not clear” (Source untraced[14]);for here the perception of visible forms is called “quite clear” in the sense of extension of the sign, while the perception of bones is called “not quite clear” in the sense of its non-extension.

111. But the words “I was intent upon this whole earth with the perception of a skeleton” (Th 18) are said of the manner of appearance to one who has acquired that perception. For just as in [the Emperor] Dhammāsoka’s time the Karavīka bird uttered a sweet song when it saw its own reflection in the looking glass walls all round and perceived Karavīkas in every direction,[15] so the Elder [Siṅgāla Pitar] thought, when he saw the sign appearing in all directions through his acquisition of the perception of a skeleton, that the whole earth was covered with bones.

112. If that is so, then is what is called “the measurelessness of the object of jhāna produced on foulness”[16] contradicted? It is not contradicted. For one man apprehends the sign in a large bloated corpse or skeleton, another in a small one. In this way the jhāna of the one has a limited object and of the other a measureless object. Or alternatively, “With a measureless object” (Dhs 182–84 in elision) is said of it referring to one who extends it, seeing no disadvantage in doing so. But it need not be extended because no benefit results.

113. The rest need not be extended likewise. Why? When a man extends the sign of in-breaths and out-breaths, only a quantity of wind is extended, and it has a definite location, [the nose-tip]. So it need not be extended because of the disadvantage and because of the definiteness of the location. And the divine abidings have living beings as their object. When a man extends the sign of these, only the quantity of living beings would be extended, and there is no purpose in that. So that also need not be extended.

114. When it is said, “Intent upon one quarter with his heart endued with lovingkindness” (D I 250), etc., that is said for the sake of comprehensive inclusion. For it is when a man develops it progressively by including living beings in one direction by one house, by two houses, etc., that he is said to be “intent upon one direction,” [113] not when he extends the sign. And there is no counterpart sign here that he might extend. Also the state of having a limited or measureless object can be understood here according to the way of inclusion, too.

115. As regards the immaterial states as object, space need not be extended since it is the mere removal of the kasiṇa [materiality]; for that should be brought to mind only as the disappearance of the kasiṇa [materiality]; if he extends it, nothing further happens. And consciousness need not be extended since it is a state consisting in an individual essence, and it is not possible to extend a state consisting in an individual essence. The disappearance of consciousness need not be extended since it is mere non-existence of consciousness. And the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception as object need not be extended since it too is a state consisting in an individual essence.[17]

116. The rest need not be extended because they have no sign. For it is the counterpart sign[18] that would be extendable, and the object of the recollection of the Buddha, etc., is not a counterpart sign. Consequently there is no need for extension there.

This is “as to extension and non-extension.”

117. 6. As to object: of these forty meditation subjects, twenty-two have counterpart signs as object, that is to say, the ten kasiṇas, the ten kinds of foulness, mindfulness of breathing, and mindfulness occupied with the body; the rest do not have counterpart signs as object. Then twelve have states consisting in individual essences as object, that is to say, eight of the ten recollections—except mindfulness of breathing and mindfulness occupied with the body—the perception of repulsiveness in nutriment, the defining of the elements, the base consisting of boundless consciousness, and the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception; and twenty-two have [counterpart] signs as object, that is to say, the ten kasiṇas, the ten kinds of foulness, mindfulness of breathing, and mindfulness occupied with the body;while the remaining six have “not-soclassifiable”[19] objects. Then eight have mobile objects in the early stage though the counterpart is stationary, that is to say, the festering, the bleeding, the worm-infested, mindfulness of breathing, the water kasiṇa, the fire kasiṇa, the air kasiṇa, and in the case of the light kasiṇa the object consisting of a circle of sunlight, etc.; the rest have immobile objects.[20] This is “as to object.”

118. 7. As to plane: here the twelve, namely, the ten kinds of foulness, mindfulness occupied with the body, and perception of repulsiveness in nutriment, do not occur among deities. These twelve and mindfulness of breathing do not occur in the Brahmā-world. But none except the four immaterial states occur in the immaterial becoming. All occur among human beings. This is “as to plane.” [114]

119. 8. As to apprehending: here the exposition should be understood according to the seen, the touched and the heard. Herein, these nineteen, that is to say, nine kasiṇas omitting the air kasiṇa and the ten kinds of foulness, must be apprehended by the seen. The meaning is that in the early stage their sign must be apprehended by constantly looking with the eye. In the case of mindfulness occupied with the body the five parts ending with skin must be apprehended by the seen and the rest by the heard, so its object must be apprehended by the seen and the heard. Mindfulness of breathing must be apprehended by the touched; the air kasiṇa by the seen and the touched; the remaining eighteen by the heard. The divine abiding of equanimity and the four immaterial states are not apprehendable by a beginner; but the remaining thirty-five are. This is “as to apprehending.”

120. 9. As to condition: of these meditation subjects nine kasiṇas omitting the space kasiṇa are conditions for the immaterial states. The ten kasiṇas are conditions for the kinds of direct-knowledge. Three divine abidings are conditions for the fourth divine abiding. Each lower immaterial state is a condition for each higher one. The base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception is a condition for the attainment of cessation. All are conditions for living in bliss, for insight, and for the fortunate kinds of becoming. This is “as to condition.”

121. 10. As to suitability to temperament: here the exposition should be understood according to what is suitable to the temperaments. That is to say: first, the ten kinds of foulness and mindfulness occupied with the body are eleven meditation subjects suitable for one of greedy temperament. The four divine abidings and four colour kasiṇas are eight suitable for one of hating temperament. Mindfulness of breathing is the one [recollection as a] meditation subject suitable for one of deluded temperament and for one of speculative temperament. The first six recollections are suitable for one of faithful temperament. Mindfulness of death, the recollection of peace, the defining of the four elements, and the perception of repulsiveness in nutriment, are four suitable for one of intelligent temperament. The remaining kasiṇas and the immaterial states are suitable for all kinds of temperament. And anyone of the kasiṇas should be limited for one of speculative temperament and measureless for one of deluded temperament. This is how the exposition should be understood here “as to suitability to temperament.”

122. All this has been stated in the form of direct opposition and complete suitability. But there is actually no profitable development that does not suppress greed, etc., and help faith, and so on. And this is said in the Meghiya Sutta: “[One] should, in addition,[21] develop these four things: foulness should be developed for the purpose of abandoning greed (lust). Loving-kindness should be developed for the purpose of abandoning ill will. [115] Mindfulness of breathing should be developed for the purpose of cutting off applied thought. Perception of impermanence should be cultivated for the purpose of eliminating the conceit, ‘I am’” (A IV 358). Also in the Rāhula Sutta, in the passage beginning, “Develop loving-kindness, Rāhula” (M I 424), seven meditation subjects are given for a single temperament. So instead of insisting on the mere letter, the intention should be sought in each instance.

This is the explanatory exposition of the meditation subject referred to by the words he should apprehend…one [meditation subject] (§28).

123. Now the words and he should apprehend are illustrated as follows. After approaching the good friend of the kind described in the explanation of the words then approach the good friend, the giver of a meditation subject (§28 and §57–73), the meditator should dedicate himself to the Blessed One, the Enlightened One, or to a teacher, and he should ask for the meditation subject with a sincere inclination [of the heart] and sincere resolution.

124. Herein, he should dedicate himself to the Blessed One, the Enlightened One, in this way: “Blessed One, I relinquish this my person to you.” For without having thus dedicated himself, when living in a remote abode he might be unable to stand fast if a frightening object made its appearance, and he might return to a village abode, become associated with laymen, take up improper search and come to ruin. But when he has dedicated himself in this way no fear arises in him if a frightening object makes its appearance; in fact only joy arises in him as he reflects: “Have you not wisely already dedicated yourself to the Enlightened One?”

125. Suppose a man had a fine piece of Kāsi cloth. He would feel grief if it were eaten by rats or moths; but if he gave it to a bhikkhu needing robes, he would feel only joy if he saw the bhikkhu tearing it up [to make his patched cloak]. And so it is with this.

126. When he dedicates himself to a teacher, he should say: “I relinquish this my person to you, venerable sir.” For one who has not dedicated his person thus becomes unresponsive to correction, hard to speak to, and unamenable to advice, or he goes where he likes without asking the teacher. Consequently the teacher does not help him with either material things or the Dhamma, and he does not train him in the cryptic books.[22] Failing to get these two kinds of help, [116] he finds no footing in the Dispensation, and he soon comes down to misconducting himself or to the lay state. But if he has dedicated his person, he is not unresponsive to correction, does not go about as he likes, is easy to speak to, and lives only in dependence on the teacher. He gets the twofold help from the teacher and attains growth, increase, and fulfilment in the Dispensation. Like the Elder CūḷaPiṇḍapātika-Tissa’s pupils.

127. Three bhikkhus came to the elder, it seems. One of them said, “Venerable sir, I am ready to fall from a cliff the height of one hundred men, if it is said to be to your advantage.” The second said, “Venerable sir, I am ready to grind away this body from the heels up without remainder on a flat stone, if it is said to be to your advantage.” The third said, “Venerable sir, I am ready to die by stopping breathing, if it is said to be to your advantage.” Observing, “These bhikkhus are certainly capable of progress,” the elder expounded a meditation subject to them. Following his advice, the three attained Arahantship.

This is the benefit in self-dedication. Hence it was said above “dedicating himself to the Blessed One, the Enlightened One, or to a teacher.”

128. With a sincere inclination [of the heart] and sincere resolution (§ 123): the meditator’s inclination should be sincere in the six modes beginning with nongreed. For it is one of such sincere inclination who arrives at one of the three kinds of enlightenment, according as it is said: “Six kinds of inclination lead to the maturing of the enlightenment of the Bodhisattas. With the inclination to nongreed, Bodhisattas see the fault in greed. With the inclination to non-hate, Bodhisattas see the fault in hate. With the inclination to non-delusion, Bodhisattas see the fault in delusion. With the inclination to renunciation, Bodhisattas see the fault in house life. With the inclination to seclusion, Bodhisattas see the fault in society. With the inclination to relinquishment, Bodhisattas see the fault in all kinds of becoming and destiny (Source untraced.)” For stream-enterers, once-returners, non-returners, those with cankers destroyed (i.e. Arahants), Paccekabuddhas, and Fully Enlightened Ones, whether past, future or present, all arrive at the distinction peculiar to each by means of these same six modes. That is why he should have sincerity of inclination in these six modes.

129. He should be whole-heartedly resolved on that. The meaning is [117] that he should be resolved upon concentration, respect concentration, incline to concentration, be resolved upon Nibbāna, respect Nibbāna, incline to Nibbāna.

130. When, with sincerity of inclination and whole-hearted resolution in this way, he asks for a meditation subject, then a teacher who has acquired the penetration of minds can know his temperament by surveying his mental conduct; and a teacher who has not can know it by putting such questions to him as: “What is your temperament?” or “What states are usually present in you?” or “What do you like bringing to mind?” or “What meditation subject does your mind favour?” When he knows, he can expound a meditation subject suitable to that temperament. And in doing so, he can expound it in three ways: it can be expounded to one who has already learnt the meditation subject by having him recite it at one or two sessions; it can be expounded to one who lives in the same place each time he comes; and to one who wants to learn it and then go elsewhere it can be expounded in such a manner that it is neither too brief nor too long.

131. Herein, when first he is explaining the earth kasiṇa, there are nine aspects that he should explain. They are the four faults of the kasiṇa, the making of a kasiṇa, the method of development for one who has made it, the two kinds of sign, the two kinds of concentration, the seven kinds of suitable and unsuitable, the ten kinds of skill in absorption, evenness of energy, and the directions for absorption.

In the case of the other meditation subjects, each should be expounded in the way appropriate to it. All this will be made clear in the directions for development. But when the meditation subject is being expounded in this way, the meditator must apprehend the sign as he listens.

132. Apprehend the sign means that he must connect each aspect thus: “This is the preceding clause, this is the subsequent clause, this is its meaning, this is its intention, this is the simile.” When he listens attentively, apprehending the sign in this way, his meditation subject is well apprehended. Then, and because of that, he successfully attains distinction, but not otherwise. This clarifies the meaning of the words “and he must apprehend.”

133. At this point the clauses approach the good friend, the giver of a meditation subject, and he should apprehend from among the forty meditation subjects one that suits his own temperament (§28) have been expounded in detail in all their aspects.

The third chapter called “The Description of Taking a Meditation Subject” in the Treatise on the Development of Concentration in the Path of Purification composed for the purpose of gladdening good people.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Sīmā—”boundary”: loosely used in this sense, it corresponds vaguely to what is meant by “parish.” In the strict sense it is the actual area (usually a “chapter house”) agreed according to the rules laid down in the Vinaya and marked by boundary stones, within which the Community (saṅgha) carries out its formal acts.

[2]:

Atthayitabba—”needed”: not in PED, not in CPD.

[3]:

Māna, usually rendered by “pride,” is rendered here both by “pride” and “conceit.” Etymologically it is derived perhaps from māneti (to honour) or mināti (to measure). In sense, however, it tends to become associated with maññati, to conceive (false notions, see M I 1), to imagine, to think (as e.g. at Nidd I 80, Vibh 390 and comy.). As one of the “defilements” (see M I 36) it is probably best rendered by “pride.” In the expression asmi-māna (often rendered by “the pride that says ‘I am’”) it more nearly approaches maññanā (false imagining, misconception, see M III 246) and is better rendered by the “conceit ‘I am,’” since the word “conceit” straddles both the meanings of “pride” (i.e. haughtiness) and “conception.”

[4]:

“‘Some’ is said with reference to the Elder Upatissa. For it is put in this way by him in the Vimuttimagga. The word ‘apparently’ indicates dissent from what follows” (Vism-mhṭ 103). A similar passage to that referred to appears in Ch. 6 (Taisho ed. p. 410a) of the Chinese version of the Vimuttimagga, the only one extant.

[5]:

Sīlaka—”good-tempered”—sukhasīla (good-natured—see §83), which = sakhila (kindly—Vism-mhṭ 104). Not in PED.

[6]:

Ukkuṭika—”springy” is glossed here by asamphuṭṭhamajjhaṃ (“not touching in the middle”—Vism-mhṭ 106). This meaning is not in PED.

[7]:

See Sn-a 544, A-a 436.

[8]:

Siṅga—”foppery” is not in PED in this sense. See Vibh 351 and commentary.

Cāpalya (cāpalla)—”personal vanity”: noun from adj. capala. The word “capala” comes in an often-repeated passage: “saṭhā māyāvino keṭubhino uddhatā unnalā capalā mukharā …” (M I 32); cf. S I 203; A III 199, etc.) and also M I 470 “uddhato hoti capalo,” with two lines lower “uddhaccaṃ cāpalyaṃ.” Cāpalya also occurs at Vibh 351 (and M II 167).

At Ma I 152 (commenting on M I 32) we find:

capalā ti pattacīvaramaṇḍanādinā cāpallena yuttā

(“interested in personal vanity consisting in adorning bowl and robe and so on”),

and at M-a III 185 (commenting on M I 470):

Uddhato hoti capalo ti uddhaccapakatiko c’eva hoti cīvaramaṇḍanā pattamaṇḍanā senāsanamaṇḍanā imassa vā pūtikāyassa kelāyanamaṇḍanā ti evaṃ vuttena taruṇadārakacāpallena samannāgato

(“‘he is distracted—or puffed up—and personally vain’: he is possessed of the callow youth’s personal vanity described as adorning the robe, adorning the bowl, adorning the lodging, or prizing and adorning this filthy body”).

This meaning is confirmed in the commentary to Vibh 251. PED does not give this meaning at all but only “fickle,” which is unsupported by the commentary. CPD (acapala) also does not give this meaning.

As to the other things listed here in the Visuddhimagga text, most will be found at M I 36. For “holding on tenaciously,” etc., see M I 43.

[10]:

Jalapūvasadisa—”like a net cake”: “A cake made like a net” (Vism-mhṭ 108); possibly what is now known in Sri Lanka as a “string hopper,” or something like it.

[12]:

“‘Kasiṇa’ is in the sense of entirety (sakalaṭṭhena)” (M-a III 260). See IV.119.

[13]:

Here ten kinds of foulness are given. But in the Suttas only either five or six of this set appear to be mentioned, that is, “Perception of a skeleton, perception of the worminfested, perception of the livid, perception of the cut-up, perception of the bloated. (see A I 42 and S V 131; A II 17 adds “perception of the festering”)” No details are given. All ten appear at Dhs 263–64 and Paṭis I 49. It will be noted that no order of progress of decay in the kinds of corpse appears here; also the instructions in Ch. VI are for contemplating actual corpses in these states. The primary purpose here is to cultivate “repulsiveness.”

Another set of nine progressive stages in the decay of a corpse, mostly different from these, is given at M I 58, 89, etc., beginning with a corpse one day old and ending with bones turned to dust. From the words “suppose a bhikkhu saw a corpse thrown on a charnel ground … he compares this same body of his with it thus, ‘This body too is of like nature, awaits a like fate, is not exempt from that’”(M I 58), it can be assumed that these nine, which are given in progressive order of decay in order to demonstrate the body’s impermanence, are not necessarily intended as contemplations of actual corpses so much as mental images to be created, the primary purpose being to cultivate impermanence. This may be why these nine are not used here (see VIII.43).

The word asubha (foul, foulness) is used both of the contemplations of corpses as here and of the contemplation of the parts of the body (A V 109).

[14]:

Also quoted in A-a V 79 on AN 11:9. Cf. Sn 1119. A similar quotation with Sopāka is found in Vism-mhṭ 334–35, see note 1 to XI.2.

[15]:

The full story, which occurs at M-a III 382–83 and elsewhere, is this: “It seems that when the Karavīka bird has pecked a sweet-flavoured mango wth its beak and savoured the dripping juice, and flapping its wings, begins to sing, then quadrupeds caper as if mad. Quadrupeds grazing in their pastures drop the grass in their mouths and listen to the sound. Beasts of prey hunting small animals pause with one foot raised. Hunted animals lose their fear of death and halt in their tracks. Birds flying in the air stay with wings outstretched. Fishes in the water keep still, not moving their fins. All listen to the sound, so beautiful is the Karavīka’s song. Dhammāsoka’s queen Asandhamittā asked the Community: ‘Venerable sirs, is there anything that sounds like the Buddha?’—‘The Karavīka birds does.’—‘Where are those birds, venerable sirs?’—‘In the Himalaya.’ She told the king: ‘Sire, I wish to hear a Karavīka bird.’ The king dispatched a gold cage with the order, ‘Let a Karavīka bird come and sit in this cage.’ The cage travelled and halted in front of a Karavīka. Thinking, ‘The cage has come at the king’s command; it is impossible not to go,’ the bird got in. The cage returned and stopped before the king. They could not get the Karavīka to utter a sound. When the king asked, ‘When do they utter a sound?’ they replied, ‘On seeing their kin.’ Then the king had it surrounded with looking-glasses. Seeing its own reflection and imagining that its relatives had come, it flapped its wings and cried out with an exquisite voice as if sounding a crystal trumpet. All the people in the city rushed about as if mad. Asandhamittā thought: ‘If the sound of this creature is so fine, what indeed can the sound of the Blessed One have been like since he had reached the glory of omniscient knowledge?’ and arousing a happiness that she never again relinquished, she became established in the fruition of stream-entry.”

[16]:

See Dhs 55; but it comes under the “… pe …,” which must be filled in from pp. 37–38, §182 and §184.

[17]:

“It is because only an abstract (parikappaja) object can be extended, not any other kind, that he said, ‘it is not possible to extend a state consisting in an individual essence’” (Vism-mhṭ 110).

[18]:

The word “nimitta” in its technical sense is consistently rendered here by the word “sign,” which corresponds very nearly if not exactly to most uses of it. It is sometimes rendered by “mark” (which over-emphasizes the concrete), and by “image” (which is not always intended). The three kinds, that is, the preliminary-work sign, learning sign and counterpart sign, do not appear in the Piṭakas. There the use rather suggests association of ideas as, for example, at M I 180, M I 119, A I 4, etc., than the more definitely visualized “image” in some instances of the “counterpart sign” described in the following chapters.

[19]:

Na-vattabba—”not so-classifiable” is an Abhidhamma shorthand term for something that, when considered under one of the triads or dyads of the Abhidhamma Mātikā (Dhs 1f.), cannot be placed under any one of the three, or two, headings.

[20]:

“‘The festering’ is a mobile object because of the oozing of the pus, ‘the bleeding’ because of the trickling of the blood, ‘the worm-infested’ because of the wriggling of the worms. The mobile aspect of the sunshine coming in through a window opening is evident, which explains why an object consisting of a circle of sunlight is called mobile” (Vism-mhṭ 110).

[21]:

“In addition to the five things” (not quoted) dealt with earlier in the sutta, namely, perfection of virtue, good friendship, hearing suitable things, energy, and understanding.

[22]:

“‘Cryptic books’: the meditation-subject books dealing with the truths, the dependent origination, etc., which are profound and associated with voidness” (Vismmhṭ 111). Cf. M-a II 264, A-a commentary to AN 4:180.