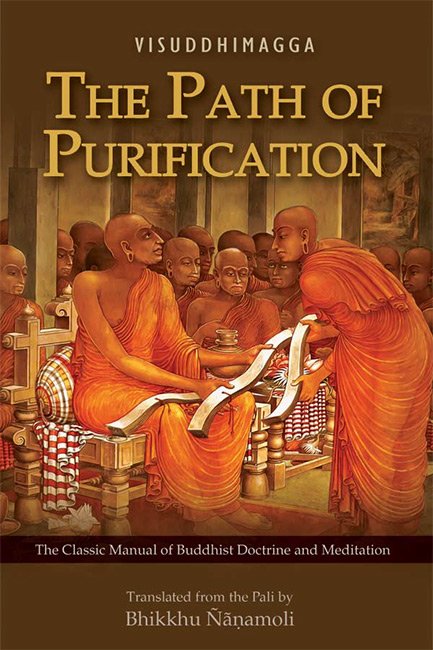

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes Virtue of the section Description of Virtue of Part 1 Virtue (Sīla) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

II. Virtue

16. However, even when this path of purification is shown in this way under the headings of virtue, concentration and understanding, each comprising various special qualities, it is still only shown extremely briefly. And so since that is insufficient to help all, there is, in order to show it in detail, the following set of questions dealing in the first place with virtue:

- What is virtue?

- In what sense is it virtue?

- What are its characteristic, function, manifestation, and proximate cause?

- What are the benefits of virtue?

- How many kinds of virtue are there?

- What is the defiling of it?

- What is the cleansing of it?

17. Here are the answers:

(i) What is Virtue? It is the states beginning with volition present in one who abstains from killing living things, etc., or in one who fulfils the practice of the duties. For this is said in the Paṭisambhidā: “What is virtue? There is virtue as volition, virtue as consciousness-concomitant,[1] virtue as restraint, [7] virtue as nontransgression” (Paṭis I 44).

Herein, virtue as volition is the volition present in one who abstains from killing living things, etc., or in one who fulfils the practice of the duties. Virtue as consciousnessconcomitant is the abstinence in one who abstains from killing living things, and so on. Furthermore, virtue as volition is the seven volitions [that accompany the first seven] of the [ten] courses of action (kamma) in one who abandons the killing of living things, and so on. Virtue as consciousness-concomitant is the [three remaining] states consisting of non-covetousness, non-ill will, and right view, stated in the way beginning, “Abandoning covetousness, he dwells with a mind free from covetousness” (D I 71).

18. Virtue as restraint should be understood here as restraint in five ways: restraint by the rules of the community (pātimokkha), restraint by mindfulness, restraint by knowledge, restraint by patience, and restraint by energy. Herein, “restraint by the Pātimokkha” is this: “He is furnished, fully furnished, with this Pātimokkha restraint. (Vibh 246)” “Restraint by mindfulness” is this: “He guards the eye faculty, enters upon restraint of the eye faculty” (D I 70). “Restraint by knowledge” is this:

“The currents in the world that flow, Ajita,” said the Blessed One,

“Are stemmed by means of mindfulness;

Restraint of currents I proclaim,

By understanding they are dammed” (Sn 1035);

and use of requisites is here combined with this. But what is called “restraint by patience” is that given in the way beginning, “He is one who bears cold and heat” (M I 10). And what is called “restraint by energy” is that given in the way beginning, “He does not endure a thought of sense desires when it arises” (M I 11); purification of livelihood is here combined with this. So this fivefold restraint, and the abstinence, in clansmen who dread evil, from any chance of transgression met with, should all be understood to be “virtue as restraint.”

Virtue as non-transgression is the non-transgression, by body or speech, of precepts of virtue that have been undertaken.

This, in the first place, is the answer to the question, “What is virtue?” [8] Now, as to the rest—

19. (ii) In what Sense is it Virtue? It is virtue (sīla) in the sense of composing (sīlana).[2] What is this composing? It is either a coordinating (samādhāna), meaning noninconsistency of bodily action, etc., due to virtuousness; or it is an upholding (upadhāraṇa),[2] meaning a state of basis (ādhāra) owing to its serving as foundation for profitable states. For those who understand etymology admit only these two meanings. Others, however, comment on the meaning here in the way beginning, “The meaning of virtue (sīla) is the meaning of head (sira), the meaning of virtue is the meaning of cool (sītala).”

20. (iii) Now, What are its Characteristic, Function, Manifestation, and Proximate Cause? Here:

The characteristic of it is composing

Even when analyzed in various ways,

As visibility is of visible data

Even when analyzed in various ways.

Just as visibleness is the characteristic of the visible-data base even when analyzed into the various categories of blue, yellow, etc., because even when analyzed into these categories it does not exceed visible-ness, so also this same composing, described above as the coordinating of bodily action, etc., and as the foundation of profitable states, is the characteristic of virtue even when analyzed into the various categories of volition, etc., because even when analyzed into these categories it does not exceed the state of coordination and foundation.

21. While such is its characteristic:

Its function has a double sense:

Action to stop misconduct, then

Achievement as the quality

Of blamelessness in virtuous men.

So what is called virtue should be understood to have the function (nature) of stopping misconduct as its function (nature) in the sense of action, and a blameless function (nature) as its function (nature) in the sense of achievement. For under [these headings of] characteristic, etc., it is action (kicca) or it is achievement (sampatti) that is called “function” (rasa—nature).

22.

Now, virtue, so say those who know,

Itself as purity will show;

And for its proximate cause they tell

The pair, conscience and shame, as well. [9]

This virtue is manifested as the kinds of purity stated thus: “Bodily purity, verbal purity, mental purity” (A I 271); it is manifested, comes to be apprehended, as a pure state. But conscience and shame are said by those who know to be its proximate cause; its near reason, is the meaning. For when conscience and shame are in existence, virtue arises and persists; and when they are not, it neither arises nor persists.

This is how virtue’s characteristic, function, manifestation, and proximate cause, should be understood.

23. (iv) What are the Benefits of Virtue? Its benefits are the acquisition of the several special qualities beginning with non-remorse. For this is said: “Ānanda, profitable habits (virtues) have non-remorse as their aim and non-remorse as their benefit” (A V 1). Also it is said further: “Householder, there are these five benefits for the virtuous in the perfecting of virtue. What five? Here, householder, one who is virtuous, possessed of virtue, obtains a large fortune as a consequence of diligence; this is the first benefit for the virtuous in the perfecting of virtue. Again, of one who is virtuous, possessed of virtue, a fair name is spread abroad; this is the second benefit for the virtuous in the perfecting of virtue. Again, whenever one who is virtuous, possessed of virtue, enters an assembly, whether of khattiyas (warriornobles) or brahmans or householders or ascetics, he does so without fear or hesitation; this is the third benefit for the virtuous in the perfecting of virtue. Again, one who is virtuous, possessed of virtue, dies unconfused; this is the fourth benefit for the virtuous in the perfecting of virtue. Again, one who is virtuous, possessed of virtue, on the breakup of the body, after death, reappears in a happy destiny, in the heavenly world; this is the fifth benefit for the virtuous in the perfecting of virtue” (D II 86). There are also the many benefits of virtue beginning with being dear and loved and ending with destruction of cankers described in the passage beginning, “If a bhikkhu should wish, ‘May I be dear to my fellows in the life of purity and loved by them, held in respect and honoured by them,’ let him perfect the virtues” (M I 33). This is how virtue has as its benefits the several special qualities beginning with non-remorse. [10]

24. Furthermore:

Dare anyone a limit place

On benefits that virtue brings,

Without which virtue clansmen find

No footing in the dispensation?No Ganges, and no Yamunā

No Sarabhū, Sarassathī,

Or flowing Aciravatī,

Or noble River of Mahī,

Is able to wash out the stain

In things that breathe here in the world;

For only virtue’s water can

Wash out the stain in living things.No breezes that come bringing rain,

No balm of yellow sandalwood,

No necklaces beside, or gems

Or soft effulgence of moonbeams,

Can here avail to calm and soothe

Men’s fevers in this world; whereas

This noble, this supremely cool,

Well-guarded virtue quells the flame.Where is there to be found the scent

That can with virtue’s scent compare,

And that is borne against the wind

As easily as with it? Where

Can such another stair be found

That climbs, as virtue does, to heaven?

Or yet another door that gives

Onto the City of Nibbāna?Shine as they may, there are no kings

Adorned with jewellery and pearls

That shine as does a man restrained

Adorned with virtue’s ornament.

Virtue entirely does away

With dread of self-blame and the like;

Their virtue to the virtuous

Gives gladness always by its fame.From this brief sketch it may be known

How virtue brings reward, and how

This root of all good qualities

Robs of its power every fault.

25. (v) Now, here is the answer to the question, How many Kinds of Virtue are there?

1. Firstly all this virtue is of one kind by reason of its own characteristic ofcomposing.

2. It is of two kinds as keeping and avoiding.

3. Likewise as that of good behaviour and that of the beginning of the life ofpurity,

4. As abstinence and non-abstinence,

5. As dependent and independent,

6. As temporary and lifelong,

7. As limited and unlimited,

8. As mundane and supramundane. [11]

9. It is of three kinds as inferior, medium, and superior.

10. Likewise as giving precedence to self, giving precedence to the world, andgiving precedence to the Dhamma,

11. As adhered to, not adhered to, and tranquillized.

12. As purified, unpurified, and dubious.

13. As that of the trainer, that of the non-trainer, and that of the neither-trainernor-non-trainer.

14. It is of four kinds as partaking of diminution, of stagnation, of distinction,of penetration.

15. Likewise as that of bhikkhus, of bhikkhunīs, of the not-fully-admitted, of the laity,

16. As natural, customary, necessary, due to previous causes,

17. As virtue of Pātimokkha restraint, of restraint of sense faculties, ofpurification of livelihood, and that concerning requisites.

18. It is of five kinds as virtue consisting in limited purification, etc.; for this issaid in the Paṭisambhidā: “Five kinds of virtue: virtue consisting in limited purification, virtue consisting in unlimited purification, virtue consisting in fulfilled purification, virtue consisting in unadhered-to purification, virtue consisting in tranquillized purification” (Paṭis I 42).

19. Likewise as abandoning, refraining, volition, restraint, and non-transgression.

26. 1. Herein, in the section dealing with that of one kind, the meaning should be understood as already stated.

2. In the section dealing with that of two kinds: fulfilling a training precept announced by the Blessed One thus: “This should be done” is keeping; not doing what is prohibited by him thus: “This should not be done” is avoiding. Herein, the wordmeaning is this: they keep (caranti) within that, they proceed as people who fulfil the virtues, thus it is keeping (cāritta); they preserve, they protect, they avoid, thus it is avoiding. Herein, keeping is accomplished by faith and energy; avoiding, by faith and mindfulness. This is how it is of two kinds as keeping and avoiding.

27. 3. In the second dyad good behaviour is the best kind of behaviour. Good behaviour itself is that of good behaviour; or what is announced for the sake of good behaviour is that of good behaviour. This is a term for virtue other than that which has livelihood as eighth.[3] It is the initial stage of the life of purity consisting in the path, thus it is that of the beginning of the life of purity. This is a term for the virtue that has livelihood as eighth. It is the initial stage of the path because it has actually to be purified in the prior stage too. Hence it is said: “But his bodily action, his verbal action, and his livelihood have already been purified earlier” (M III 289). Or the training precepts called “lesser and minor” (D II 154) [12] are that of good behaviour; the rest are that of the beginning of the life of purity. Or what is included in the Double Code (the bhikkhus’ and bhikkhunīs’ Pātimokkha) is that of the beginning of the life of purity; and that included in the duties set out in the Khandhakas [of Vinaya] is that of good behaviour. Through its perfection that of the beginning of the life of purity comes to be perfected. Hence it is said also “that this bhikkhu shall fulfil the state consisting in the beginning of the life of purity without having fulfilled the state consisting in good behaviour—that is not possible” (A III 14–15). So it is of two kinds as that of good behaviour and that of the beginning of the life of purity.

28. 4. In the third dyad virtue as abstinence is simply abstention from killing living things, etc.; the other kinds consisting in volition, etc., are virtue as non-abstinence. So it is of two kinds as abstinence and non-abstinence.

29. 5. In the fourth dyad there are two kinds of dependence: dependence through craving and dependence through [false] views. Herein, that produced by one who wishes for a fortunate kind of becoming thus, “Through this virtuous conduct [rite] I shall become a [great] deity or some [minor] deity” (M I 102), is dependent through craving. That produced through such [false] view about purification as “Purification is through virtuous conduct” (Vibh 374) is dependent through [false] view. But the supramundane, and the mundane that is the prerequisite for the aforesaid supramundane, are independent. So it is of two kinds as dependent and independent.

30. 6. In the fifth dyad temporary virtue is that undertaken after deciding on a time limit. Lifelong virtue is that practiced in the same way but undertaking it for as long as life lasts. So it is of two kinds as temporary and lifelong.

31. 7. In the sixth dyad the limited is that seen to be limited by gain, fame, relatives, limbs, or life. The opposite is unlimited. And this is said in the Paṭisambhidā: “What is the virtue that has a limit? There is virtue that has gain as its limit, there is virtue that has fame as its limit, there is virtue that has relatives as its limit, there is virtue that has limbs as its limit, there is virtue that has life as its limit. What is virtue that has gain as its limit? Here someone with gain as cause, with gain as condition, with gain as reason, transgresses a training precept as undertaken: that virtue has gain as its limit” (Paṭis I 43), [13] and the rest should be elaborated in the same way. Also in the answer dealing with the unlimited it is said: “What is virtue that does not have gain as its limit? Here someone does not, with gain as cause, with gain as condition, with gain as reason, even arouse the thought of transgressing a training precept as undertaken, how then shall he actually transgress it? That virtue does not have gain as its limit” (Paṭis I 44), and the rest should be elaborated in the same way. So it is of two kinds as limited and unlimited.

32. 8. In the seventh dyad all virtue subject to cankers is mundane; that not subject to cankers is supramundane. Herein, the mundane brings about improvement in future becoming and is a prerequisite for the escape from becoming, according as it is said: “Discipline is for the purpose of restraint, restraint is for the purpose of nonremorse, non-remorse is for the purpose of gladdening, gladdening is for the purpose of happiness, happiness is for the purpose of tranquillity, tranquillity is for the purpose of bliss, bliss is for the purpose of concentration, concentration is for the purpose of correct knowledge and vision, correct knowledge and vision is for the purpose of dispassion, dispassion is for the purpose of fading away [of greed], fading away is for the purpose of deliverance, deliverance is for the purpose of knowledge and vision of deliverance, knowledge and vision of deliverance is for the purpose of complete extinction [of craving, etc.] through not clinging. Talk has that purpose, counsel has that purpose, support has that purpose, giving ear has that purpose, that is to say, the liberation of the mind through not clinging” (Vin V 164). The supramundane brings about the escape from becoming and is the plane of reviewing knowledge. So it is of two kinds as mundane and supramundane.

33. 9. In the first of the triads the inferior is produced by inferior zeal, [purity of] consciousness, energy, or inquiry; the medium is produced by medium zeal, etc.; the superior, by superior (zeal, and so on). That undertaken out of desire for fame is inferior; that undertaken out of desire for the fruits of merit is medium; that undertaken for the sake of the noble state thus, “This has to be done” is superior. Or again, that defiled by self-praise and disparagement of others, etc., thus, “I am possessed of virtue, but these other bhikkhus are ill-conducted and evil-natured” (M I 193), is inferior; undefiled mundane virtue is medium;supramundane is superior. Or again, that motivated by craving, the purpose of which is to enjoy continued existence, is inferior; that practiced for the purpose of one’s own deliverance is medium; the virtue of the perfections practiced for the deliverance of all beings is superior. So it is of three kinds as inferior, medium, and superior.

34. 10. In the second triad that practiced out of self-regard by one who regards self and desires to abandon what is unbecoming to self [14] is virtue giving precedence to self. That practiced out of regard for the world and out of desire to ward off the censure of the world is virtue giving precedence to the world. That practiced out of regard for the Dhamma and out of desire to honour the majesty of the Dhamma is virtue giving precedence to the Dhamma. So it is of three kinds as giving precedence to self, and so on.

35. 11. In the third triad the virtue that in the dyads was called dependent (no. 5) is adhered-to because it is adhered-to through craving and [false] view. That practiced by the magnanimous ordinary man as the prerequisite of the path, and that associated with the path in trainers, are not-adhered-to. That associated with trainers’ and non-trainers’ fruition is tranquillized. So it is of three kinds as adhered-to, and so on.

36. 12. In the fourth triad that fulfilled by one who has committed no offence or has made amends after committing one is pure. So long as he has not made amends after committing an offence it is impure. Virtue in one who is dubious about whether a thing constitutes an offence or about what grade of offence has been committed or about whether he has committed an offence is dubious. Herein, the meditator should purify impure virtue. If dubious, he should avoid cases about which he is doubtful and should get his doubts cleared up. In this way his mind will be kept at rest. So it is of three kinds as pure, and so on.

37. 13. In the fifth triad the virtue associated with the four paths and with the [first] three fruitions is that of the trainer. That associated with the fruition of Arahantship is that of the non-trainer. The remaining kinds are that of the neithertrainer-nor-non-trainer. So it is of three kinds as that of the trainer, and so on.

38. But in the world the nature of such and such beings is called their “habit” (sīla) of which they say: “This one is of happy habit (sukha-sīla), this one is of unhappy habit, this one is of quarrelsome habit, this one is of dandified habit.” Because of that it is said in the Paṭisambhidā figuratively: “Three kinds of virtue (habit): profitable virtue, unprofitable virtue, indeterminate virtue” (Paṭis I 44). So it is also called of three kinds as profitable, and so on. Of these, the unprofitable is not included here since it has nothing whatever to do with the headings beginning with the characteristic, which define virtue in the sense intended in this [chapter]. So the threefoldness should be understood only in the way already stated.

39. 14. In the first of the tetrads:

The unvirtuous he cultivates,

He visits not the virtuous,

And in his ignorance he sees

No fault in a transgression here, [15]

With wrong thoughts often in his mind

His faculties he will not guard—

Virtue in such a constitution

Comes to partake of diminution.But he whose mind is satisfied.

With virtue that has been achieved,

Who never thinks to stir himself

And take a meditation subject up,

Contented with mere virtuousness,

Nor striving for a higher state—

His virtue bears the appellation

Of that partaking of stagnation.But who, possessed of virtue, strives

With concentration for his aim—

That bhikkhu’s virtue in its function

Is called partaking of distinction.Who finds mere virtue not enough

But has dispassion for his goal—

His virtue through such aspiration

Comes to partake of penetration.

So it is of four kinds as partaking of diminution, and so on.

40. 15. In the second tetrad there are training precepts announced for bhikkhus to keep irrespective of what is announced for bhikkhunīs. This is the virtue of bhikkhus. There are training precepts announced for bhikkhunīs to keep irrespective of what is announced for bhikkhus. This is the virtue of bhikkhunīs. The ten precepts of virtue for male and female novices are the virtue of the not fully admitted. The five training precepts—ten when possible—as a permanent undertaking and eight as the factors of the Uposatha Day,[4] for male and female lay followers are the virtue of the laity. So it is of four kinds as the virtue of bhikkhus, and so on.

41. 16. In the third tetrad the non-transgression on the part of Uttarakuru human beings is natural virtue. Each clan’s or locality’s or sect’s own rules of conduct are customary virtue. The virtue of the Bodhisatta’s mother described thus: “It is the necessary rule, Ānanda, that when the Bodhisatta has descended into his mother’s womb, no thought of men that is connected with the cords of sense desire comes to her” (D II 13), is necessary virtue. But the virtue of such pure beings as Mahā Kassapa, etc., and of the Bodhisatta in his various births is virtue due to previous causes. So it is of four kinds as natural virtue, and so on.

42. 17. In the fourth tetrad:

(a) The virtue described by the Blessed One thus: “Here a bhikkhu dwellsrestrained with the Pātimokkha restraint, possessed of the [proper] conduct and resort, and seeing fear in the slightest fault, he trains himself by undertaking the precepts of training, (Vibh 244)” is virtue of Pātimokkha restraint.

(b) That described thus: “On seeing a visible object with the eye, [16] heapprehends neither the signs nor the particulars through which, if he left the eye faculty unguarded, evil and unprofitable states of covetousness and grief might invade him; he enters upon the way of its restraint, he guards the eye faculty, undertakes the restraint of the eye faculty. On hearing a sound with the ear … On smelling an odour with the nose … On tasting a flavour with the tongue … On touching a tangible object with the body … On cognizing a mental object with the mind, he apprehends neither the signs nor the particulars through which, if he left the mind faculty unguarded, evil and unprofitable states of covetousness and grief might invade him; he enters upon the way of its restraint, he guards the mind faculty, undertakes the restraint of the mind faculty (M I 180), is virtue of restraint of the sense faculties.

(c) Abstinence from such wrong livelihood as entails transgression of the six trainingprecepts announced with respect to livelihood and entails the evil states beginning with “Scheming, talking, hinting, belittling, pursuing gain with gain” (M II 75) is virtue of livelihood purification.

(d) Use of the four requisites that is purified by the reflection stated in the waybeginning, “Reflecting wisely, he uses the robe only for protection from cold” (M I 10) is called virtue concerning requisites.

43. Here is an explanatory exposition together with a word commentary starting from the beginning.

(a) Here: in this dispensation. A bhikkhu: a clansman who has gone forth out of faith and is so styled because he sees fear in the round of rebirths (saṃsāre bhayaṃ ikkhanatā) or because he wears cloth garments that are torn and pieced together, and so on.

Restrained with the Pātimokkha restraint: here “Pātimokkha” (Rule of the Community)[5] is the virtue of the training precepts; for it frees (mokkheti) him who protects (pāti) it, guards it, it sets him free (mocayati) from the pains of the states of loss, etc., that is why it is called Pātimokkha. “Restraint” is restraining; this is a term for bodily and verbal non-transgression. The Pātimokkha itself as restraint is “Pātimokkha restraint.” “Restrained with the Pātimokkha restraint” is restrained by means of the restraint consisting in that Pātimokkha; he has it, possesses it, is the meaning. Dwells: bears himself in one of the postures. [17]

44. The meaning of possessed of [the proper] conduct and resort, etc., should be understood in the way in which it is given in the text. For this is said: “Possessed of [the proper] conduct and resort: there is [proper] conduct and improper conduct. Herein, what is improper conduct? Bodily transgression, verbal transgression, bodily and verbal transgression—this is called improper conduct. Also all unvirtuousness is improper conduct. Here someone makes a livelihood by gifts of bamboos, or by gifts of leaves, or by gifts of flowers, fruits, bathing powder, and tooth sticks, or by flattery, or by bean-soupery, or by fondling, or by going on errands on foot, or by one or other of the sorts of wrong livelihood condemned by the Buddhas—this is called improper conduct. Herein, what is [proper] conduct? Bodily non-transgression, verbal non-transgression, bodily and verbal non-transgression—this is called [proper] conduct. Also all restraint through virtue is [proper] conduct. Here someone “does not make a livelihood by gifts of bamboos, or by gifts of leaves, or by gifts of flowers, fruits, bathing powder, and tooth sticks, or by flattery, or by bean-soupery, or by fondling, or by going on errands on foot, or by one or other of the sorts of wrong livelihood condemned by the Buddhas—this is called [proper] conduct.”

45. “[Proper] resort: there is [proper] resort and improper resort. Herein, what is improper resort? Here someone has prostitutes as resort, or he has widows, old maids, eunuchs, bhikkhunīs, or taverns as resort; or he dwells associated with kings, kings’ ministers, sectarians, sectarians’ disciples, in unbecoming association with laymen; or he cultivates, frequents, honours, such families as are faithless, untrusting, abusive and rude, who wish harm, wish ill, wish woe, wish no surcease of bondage, for bhikkhus and bhikkhunīs, for male and female devotees [18]—this is called improper resort. Herein, what is [proper] resort? Here someone does not have prostitutes as resort … or taverns as resort; he does not dwell associated with kings … sectarians’ disciples, in unbecoming association with laymen; he cultivates, frequents, honours, such families as are faithful and trusting, who are a solace, where the yellow cloth glows, where the breeze of sages blows, who wish good, wish well, wish joy, wish surcease of bondage, for bhikkhus and bhikkhunīs, for male and female devotees—this is called [proper] resort. Thus he is furnished with, fully furnished with, provided with, fully provided with, supplied with, possessed of, endowed with, this [proper] conduct and this [proper] resort. Hence it is said,’Possessed of [the proper] conduct and resort’” (Vibh 246–47).

46. Furthermore, [proper] conduct and resort should also be understood here in the following way; for improper conduct is twofold as bodily and verbal. Herein, what is bodily improper conduct? “Here someone acts disrespectfully before the Community, and he stands jostling elder bhikkhus, sits jostling them, stands in front of them, sits in front of them, sits on a high seat, sits with his head covered, talks standing up, talks waving his arms … walks with sandals while elder bhikkhus walk without sandals, walks on a high walk while they walk on a low walk, walks on a walk while they walk on the ground … stands pushing elder bhikkhus, sits pushing them, prevents new bhikkhus from getting a seat … and in the bath house … without asking elder bhikkhus he puts wood on [the stove] … bolts the door … and at the bathing place he enters the water jostling elder bhikkhus, enters it in front of them, bathes jostling them, bathes in front of them, comes out jostling them, comes out in front of them … and entering inside a house he goes jostling elder bhikkhus, goes in front of them, pushing forward he goes in front of them … and where families have inner private screened rooms in which the women of the family … the girls of the family, sit, there he enters abruptly, and he strokes a child’s head” (Nidd I 228–29). This is called bodily improper conduct.

47. Herein, what is verbal improper conduct? “Here someone acts disrespectfully before the Community. Without asking elder bhikkhus he talks on the Dhamma, answers questions, recites the Pātimokkha, talks standing up, [19] talks waving his arms … having entered inside a house, he speaks to a woman or a girl thus: ‘You, soand-so of such-and-such a clan, what is there? Is there rice gruel? Is there cooked rice? Is there any hard food to eat? What shall we drink? What hard food shall we eat? What soft food shall we eat? Or what will you give me?’—he chatters like this” (Nidd I 230). This is called verbal improper conduct.

48. Proper conduct should be understood in the opposite sense to that. Furthermore, a bhikkhu is respectful, deferential, possessed of conscience and shame, wears his inner robe properly, wears his upper robe properly, his manner inspires confidence whether in moving forwards or backwards, looking ahead or aside, bending or stretching, his eyes are downcast, he has (a good) deportment, he guards the doors of his sense faculties, knows the right measure in eating, is devoted to wakefulness, possesses mindfulness and full awareness, wants little, is contented, is strenuous, is a careful observer of good behaviour, and treats the teachers with great respect. This is called (proper) conduct.

This firstly is how (proper) conduct should be understood.

49. (Proper) resort is of three kinds: (proper) resort as support, (proper) resort as guarding, and (proper) resort as anchoring. Herein, what is (proper) resort as support? A good friend who exhibits the instances of talk,[6] in whose presence one hears what has not been heard, corrects what has been heard, gets rid of doubt, rectifies one’s view, and gains confidence; or by training under whom one grows in faith, virtue, learning, generosity and understanding—this is called (proper) resort as support.

50. What is (proper) resort as guarding? Here “A bhikkhu, having entered inside a house, having gone into a street, goes with downcast eyes, seeing the length of a plough yoke, restrained, not looking at an elephant, not looking at a horse, a carriage, a pedestrian, a woman, a man, not looking up, not looking down, not staring this way and that” (Nidd I 474). This is called (proper) resort as guarding.

51. What is (proper) resort as anchoring? It is the four foundations of mindfulness on which the mind is anchored; for this is said by the Blessed One: “Bhikkhus, what is a bhikkhu’s resort, his own native place? It is these four foundations of mindfulness” (S V 148). This is called (proper) resort as anchoring.

Being thus furnished with … endowed with, this (proper) conduct and this (proper) resort, he is also on that account called “one possessed of (proper) conduct and resort.” [20]

52. Seeing fear in the slightest fault (§42): one who has the habit (sīla) of seeing fear in faults of the minutest measure, of such kinds as unintentional contravening of a minor training rule of the Pātimokkha, or the arising of unprofitable thoughts. He trains himself by undertaking (samādāya) the precepts of training: whatever there is among the precepts of training to be trained in, in all that he trains by taking it up rightly (sammā ādāya). And here, as far as the words, “one restrained by the Pātimokkha restraint,” virtue of Pātimokkha restraint is shown by discourse in terms of persons.[7] But all that beginning with the words, “possessed of [proper] conduct and resort” should be understood as said in order to show the way of practice that perfects that virtue in him who so practices it.

53. (b) Now, as regards the virtue of restraint of faculties shown next to that in the way beginning, “on seeing a visible object with the eye,” herein he is a bhikkhu established in the virtue of Pātimokkha restraint. On seeing a visible object with the eye: on seeing a visible object with the eye-consciousness that is capable of seeing visible objects and has borrowed the name “eye” from its instrument. But the Ancients (porāṇā) said: “The eye does not see a visible object because it has no mind. The mind does not see because it has no eyes. But when there is the impingement of door and object he sees by means of the consciousness that has eye-sensitivity as its physical basis. Now, (an idiom) such as this is called an ‘accessory locution’ (sasambhārakathā), like ‘He shot him with his bow,’ and so on. So the meaning here is this: ‘On seeing a visible object with eye-consciousness.’”[8]

54. Apprehends neither the signs: he does not apprehend the sign of woman or man, or any sign that is a basis for defilement such as the sign of beauty, etc.; he stops at what is merely seen. Nor the particulars: he does not apprehend any aspect classed as hand, foot, smile, laughter, talk, looking ahead, looking aside, etc., which has acquired the name “particular” (anubyañjana) because of its particularizing (anu anu byañjanato) defilements, because of its making them manifest themselves. He only apprehends what is really there. Like the Elder Mahā Tissa who dwelt at Cetiyapabbata.

55. It seems that as the elder was on his way from Cetiyapabbata to Anurādhapura for alms, a certain daughterinlaw of a clan, who had quarrelled with her husband and had set out early from Anurādhapura all dressed up and tricked out like a celestial nymph to go to her relatives’ home, saw him on the road, and being lowminded, [21] she laughed a loud laugh. [Wondering] “What is that?” the elder looked up and finding in the bones of her teeth the perception of foulness (ugliness), he reached Arahantship.[9] Hence it was said:

“He saw the bones that were her teeth,

And kept in mind his first perception;

And standing on that very spot

The elder became an Arahant.”

But her husband, who was going after her, saw the elder and asked, “Venerable sir, did you by any chance see a woman?” The elder told him:

“Whether it was a man or woman

That went by I noticed not,

But only that on this high road

There goes a group of bones.”

56. As to the words through which, etc., the meaning is: by reason of which, because of which non-restraint of the eye faculty, if he, if that person, left the eye faculty unguarded, remained with the eye door unclosed by the door-panel of mindfulness, these states of covetousness, etc., might invade, might pursue, might threaten, him. He enters upon the way of its restraint: he enters upon the way of closing that eye faculty by the door-panel of mindfulness. It is the same one of whom it is said he guards the eye faculty, undertakes the restraint of the eye faculty.

57. Herein, there is neither restraint nor non-restraint in the actual eye faculty, since neither mindfulness nor forgetfulness arises in dependence on eye-sensitivity. On the contrary when a visible datum as object comes into the eye’s focus, then, after the life-continuum has arisen twice and ceased, the functional mind-element accomplishing the function of adverting arises and ceases. After that, eyeconsciousness with the function of seeing;after that, resultant mind-element with the function of receiving; after that, resultant root-causeless mind-consciousnesselement with the function of investigating; after that, functional root-causeless mind-consciousness-element accomplishing the function of determining arises and ceases. Next to that, impulsion impels.[10] Herein, there is neither restraint nor nonrestraint on the occasion of the life-continuum, or on any of the occasions beginning with adverting. But there is non-restraint if unvirtuousness or forgetfulness or unknowing or impatience or idleness arises at the moment of impulsion. When this happens, it is called “non-restraint in the eye faculty.” [22]

58. Why is that? Because when this happens, the door is not guarded, nor are the life-continuum and the consciousnesses of the cognitive series. Like what? Just as, when a city’s four gates are not secured, although inside the city house doors, storehouses, rooms, etc., are secured, yet all property inside the city is unguarded and unprotected since robbers coming in by the city gates can do as they please, so too, when unvirtuousness, etc., arise in impulsion in which there is no restraint, then the door too is unguarded, and so also are the life-continuum and the consciousnesses of the cognitive series beginning with adverting. But when virtue, etc., has arisen in it, then the door too is guarded and so also are the life-continuum and the consciousnesses of the cognitive series beginning with adverting. Like what? Just as, when the city gates are secured, although inside the city the houses, etc., are not secured, yet all property inside the city is well guarded, well protected, since when the city gates are shut there is no ingress for robbers, so too, when virtue, etc., have arisen in impulsion, the door too is guarded and so also are the life-continuum and the consciousnesses of the cognitive series beginning with adverting. Thus although it actually arises at the moment of impulsion, it is nevertheless called “restraint in the eye faculty.”

59. So also as regards the phrases on hearing a sound with the ear and so on. So it is this virtue, which in brief has the characteristic of avoiding apprehension of signs entailing defilement with respect to visible objects, etc., that should be understood as virtue of restraint of faculties.

60. (c) Now, as regards the virtue of livelihood purification mentioned above next to the virtue of restraint of the faculties (§42), the words of the six precepts announced on account of livelihood mean, of the following six training precepts announced thus: “With livelihood as cause, with livelihood as reason, one of evil wishes, a prey to wishes, lays claim to a higher than human state that is non-existent, not a fact,” the contravention of which is defeat (expulsion from the Order); “with livelihood as cause, with livelihood as reason, he acts as go-between,” the contravention of which is an offence entailing a meeting of the Order; “with livelihood as cause, with livelihood as reason, he says, ‘A bhikkhu who lives in your monastery is an Arahant,’” the contravention of which is a serious offence in one who is aware of it; “with livelihood as cause, with livelihood as reason, a bhikkhu who is not sick eats superior food that he has ordered for his own use,” the contravention of which is an offence requiring expiation: “With livelihood as cause, with livelihood as reason, a bhikkhunī who is not sick eats superior food that she has ordered for her own use,” the contravention of which is an offence requiring confession; “with livelihood as cause, with livelihood as reason, one who is not sick eats curry or boiled rice [23] that he has ordered for his own use,” the contravention of which is an offence of wrongdoing (Vin V 146). Of these six precepts.[11]

61. As regards scheming, etc. (§42), this is the text: “Herein, what is scheming? It is the grimacing, grimacery, scheming, schemery, schemedness,[12] by what is called rejection of requisites or by indirect talk, or it is the disposing, posing, composing, of the deportment on the part of one bent on gain, honour and renown, of one of evil wishes, a prey to wishes—this is called scheming.

62.”Herein, what is talking? Talking at others, talking, talking round, talking up, continual talking up, persuading, continual persuading, suggesting, continual suggesting, ingratiating chatter, flattery, bean-soupery, fondling, on the part of one bent on gain, honour and renown, of one of evil wishes, a prey to wishes—this is called talking.

63.”Herein, what is hinting? A sign to others, giving a sign, indication, giving indication, indirect talk, roundabout talk, on the part of one bent on gain, honour and renown, of one of evil wishes, a prey to wishes—this is called hinting.

64.”Herein, what is belittling? Abusing of others, disparaging, reproaching, snubbing, continual snubbing, ridicule, continual ridicule, denigration, continual denigration, tale-bearing, backbiting, on the part of one bent on gain, honour and renown, of one of evil wishes, a prey to wishes—this is called belittling.

65.”Herein, what is pursuing gain with gain? Seeking, seeking for, seeking out, going in search of, searching for, searching out material goods by means of material goods, such as carrying there goods that have been got from here, or carrying here goods that have been got from there, by one bent on gain, honour and renown, by one of evil wishes, a prey to wishes—this is called pursuing gain with gain.”[13] (Vibh 352–53)

66. The meaning of this text should be understood as follows: Firstly, as regards description of scheming: on the part of one bent on gain, honour and renown is on the part of one who is bent on gain, on honour, and on reputation; on the part of one who longs for them, is the meaning. [24] Of one of evil wishes: of one who wants to show qualities that he has not got. A prey to wishes:[14] the meaning is, of one who is attacked by them. And after this the passage beginning or by what is called rejection of requisites is given in order to show the three instances of scheming given in the Mahāniddesa as rejection of requisites, indirect talk, and that based on deportment.

67. Herein, [a bhikkhu] is invited to accept robes, etc., and, precisely because he wants them, he refuses them out of evil wishes. And then, since he knows that those householders believe in him implicitly when they think, “Oh, how few are our lord’s wishes! He will not accept a thing!” and they put fine robes, etc., before him by various means, he then accepts, making a show that he wants to be compassionate towards them—it is this hypocrisy of his, which becomes the cause of their subsequently bringing them even by cartloads, that should be understood as the instance of scheming called rejection of requisites.

68. For this is said in the Mahāniddesa: “What is the instance of scheming called rejection of requisites? Here householders invite bhikkhus [to accept] robes, alms food, resting place, and the requisite of medicine as cure for the sick. One who is of evil wishes, a prey to wishes, wanting robes … alms food … resting place … the requisite of medicine as cure for the sick, refuses robes … alms food … resting place … the requisite of medicine as cure for the sick, because he wants more. He says: ‘What has an ascetic to do with expensive robes? It is proper for an ascetic to gather rags from a charnel ground or from a rubbish heap or from a shop and make them into a patchwork cloak to wear. What has an ascetic to do with expensive alms food? It is proper for an ascetic to get his living by the dropping of lumps [of food into his bowl] while he wanders for gleanings. What has an ascetic to do with an expensive resting place? It is proper for an ascetic to be a tree-root-dweller or an open-air-dweller. What has an ascetic to do with an expensive requisite of medicine as cure for the sick? It is proper for an ascetic to cure himself with putrid urine[15] and broken gallnuts.’ Accordingly he wears a coarse robe, eats coarse alms food, [25] uses a coarse resting place, uses a coarse requisite of medicine as cure for the sick. Then householders think, ‘This ascetic has few wishes, is content, is secluded, keeps aloof from company, is strenuous, is a preacher of asceticism,’ and they invite him more and more [to accept] robes, alms food, resting places, and the requisite of medicine as cure for the sick. He says: ‘With three things present a faithful clansman produces much merit: with faith present a faithful clansman produces much merit, with goods to be given present a faithful clansman produces much merit, with those worthy to receive present a faithful clansman produces much merit. You have faith; the goods to be given are here; and I am here to accept. If I do not accept, then you will be deprived of the merit. That is no good to me. Rather will I accept out of compassion for you.” Accordingly he accepts many robes, he accepts much alms food, he accepts many resting places, he accepts many requisites of medicine as cure for the sick. Such grimacing, grimacery, scheming, schemery, schemedness, is known as the instance of scheming called rejection of requisites’ (Nidd I 224–25).

69. It is hypocrisy on the part of one of evil wishes, who gives it to be understood verbally in some way or other that he has attained a higher than human state, that should be understood as the instance of scheming called indirect talk, according as it is said: “What is the instance of scheming called indirect talk? Here someone of evil wishes, a prey to wishes, eager to be admired, [thinking] ‘Thus people will admire me’ speaks words about the noble state. He says, ‘He who wears such a robe is a very important ascetic.’ He says, ‘He who carries such a bowl, metal cup, water filler, water strainer, key, wears such a waist band, sandals, is a very important ascetic.’ He says, ‘He who has such a preceptor … teacher … who has the same preceptor, who has the same teacher, who has such a friend, associate, intimate, companion; he who lives in such a monastery, lean-to, mansion, villa,[16] cave, grotto, hut, pavilion, watch tower, hall, barn, meeting hall, [26] room, at such a tree root, is a very important ascetic.’ Or alternatively, all-gushing, all-grimacing, all-scheming, all-talkative, with an expression of admiration, he utters such deep, mysterious, cunning, obscure, supramundane talk suggestive of voidness as ‘This ascetic is an obtainer of peaceful abidings and attainments such as these.’ Such grimacing, grimacery, scheming, schemery, schemedness, is known as the instance of scheming called indirect talk” (Nidd I 226–27).

70. It is hypocrisy on the part of one of evil wishes, which takes the form of deportment influenced by eagerness to be admired, that should be understood as the instance of scheming dependent on deportment, according as it is said: “What is the instance of scheming called deportment? Here someone of evil wishes, a prey to wishes, eager to be admired, [thinking] ‘Thus people will admire me,’ composes his way of walking, composes his way of lying down;he walks studiedly, stands studiedly, sits studiedly, lies down studiedly; he walks as though concentrated, stands, sits, lies down as though concentrated;and he is one who meditates in public. Such disposing, posing, composing, of deportment, grimacing, grimacery, scheming, schemery, schemedness, is known as the instance of scheming called deportment” (Nidd I 225–26).

71. Herein, the words by what is called rejection of requisites (§61) mean: by what is called thus “rejection of requisites”; or they mean: by means of the rejection of requisites that is so called. By indirect talk means: by talking near to the subject. Of deportment means: of the four modes of deportment (postures). Disposing is initial posing, or careful posing. Posing is the manner of posing. Composing is prearranging; assuming a trust-inspiring attitude, is what is meant. Grimacing is making grimaces by showing great intenseness; facial contraction is what is meant. One who has the habit of making grimaces is a grimacer. The grimacer’s state is grimacery. Scheming is hypocrisy. The way (āyanā) of a schemer (kuha) is schemery (kuhāyanā). The state of what is schemed is schemedness.

72. In the description of talking: talking at is talking thus on seeing people coming to the monastery, “What have you come for, good people? What, to invite bhikkhus? If it is that, then go along and I shall come later with [my bowl],” etc.; or alternatively, talking at is talking by advertising oneself thus, “I am Tissa, the king trusts me, such and such king’s ministers trust me.” [27] Talking is the same kind of talking on being asked a question. Talking round is roundly talking by one who is afraid of householders’ displeasure because he has given occasion for it. Talking up is talking by extolling people thus, “He is a great land-owner, a great ship-owner, a great lord of giving.” Continual talking up is talking by extolling [people] in all ways.

73. Persuading is progressively involving[17] [people] thus, “Lay followers, formerly you used to give first-fruit alms at such a time; why do you not do so now?” until they say, “We shall give, venerable sir, we have had no opportunity,” etc.; entangling, is what is meant. Or alternatively, seeing someone with sugarcane in his hand, he asks, “Where are you coming from, lay follower?”—”From the sugarcane field, venerable sir”—”Is the sugarcane sweet there?”—”One can find out by eating, venerable sir”—”It is not allowed, lay follower, for bhikkhus to say ‘Give [me some] sugarcane.’” Such entangling talk from such an entangler is persuading. Persuading again and again in all ways is continual persuading.

74. Suggesting is insinuating by specifying thus, “That family alone understands me; if there is anything to be given there, they give it to me only”; pointing to, is what is meant. And here the story of the oil-seller should be told.[18] Suggesting in all ways again and again is continual suggesting.

75. Ingratiating chatter is endearing chatter repeated again and again without regard to whether it is in conformity with truth and Dhamma. Flattery is speaking humbly, always maintaining an attitude of inferiority. Bean-soupery is resemblance to bean soup; for just as when beans are being cooked only a few do not get cooked, the rest get cooked, so too the person in whose speech only a little is true, the rest being false, is called a “bean soup”; his state is bean-soupery.

76. Fondling is the state of the act of fondling. [28] For when a man fondles children on his lap or on his shoulder like a nurse—he nurses, is the meaning—that fondler’s act is the act of fondling. The state of the act of fondling is fondling.

77. In the description of hinting (nemittikatā): a sign (nimitta) is any bodily or verbal act that gets others to give requisites. Giving a sign is making a sign such as “What have you got to eat?”, etc., on seeing [people] going along with food. Indication is talk that alludes to requisites. Giving indication: on seeing cowboys, he asks, “Are these milk cows’ calves or buttermilk cows’ calves?” and when it is said, “They are milk cows’ calves, venerable sir,” [he remarks] “They are not milk cows’ calves. If they were milk cows’ calves the bhikkhus would be getting milk,” etc.; and his getting it to the knowledge of the boys’ parents in this way, and so making them give milk, is giving indication.

78. Indirect talk is talk that keeps near [to the subject]. And here there should be told the story of the bhikkhu supported by a family. A bhikkhu, it seems, who was supported by a family went into the house wanting to eat and sat down. The mistress of the house was unwilling to give. On seeing him she said, “There is no rice,” and she went to a neighbour’s house as though to get rice. The bhikkhu went into the storeroom. Looking round, he saw sugarcane in the corner behind the door, sugar in a bowl, a string of salt fish in a basket, rice in a jar, and ghee in a pot. He came out and sat down. When the housewife came back, she said, “I did not get any rice.” The bhikkhu said, “Lay follower, I saw a sign just now that alms will not be easy to get today.”—“What, venerable sir?”—”I saw a snake that was like sugarcane put in the corner behind the door; looking for something to hit it with, I saw a stone like a lump of sugar in a bowl. When the snake had been hit with the clod, it spread out a hood like a string of salt fish in a basket, and its teeth as it tried to bite the clod were like rice grains in a jar. Then the saliva mixed with poison that came out to its mouth in its fury was like ghee put in a pot.” She thought, “There is no hoodwinking the shaveling,” so she gave him the sugarcane [29] and she cooked the rice and gave it all to him with the ghee, the sugar and the fish.

79. Such talk that keeps near [to the subject] should be understood as indirect talk. Roundabout talk is talking round and round [the subject] as much as is allowed.

80. In the description of belittling: abusing is abusing by means of the ten instances of abuse.[19] Disparaging is contemptuous talk. Reproaching is enumeration of faults such as “He is faithless, he is an unbeliever.” Snubbing is taking up verbally thus, “Don’t say that here.” Snubbing in all ways, giving grounds and reasons, is continual snubbing. Or alternatively, when someone does not give, taking him up thus, “Oh, the prince of givers!” is snubbing; and the thorough snubbing thus, “A mighty prince of givers!” is continual snubbing. Ridicule is making fun of someone thus, “What sort of a life has this man who eats up his seed [grain]?” Continual ridicule is making fun of him more thoroughly thus, “What, you say this man is not a giver who always gives the words ‘There is nothing’ to everyone?”

81. Denigration[20] is denigrating someone by saying that he is not a giver, or by censuring him. All-round denigration is continual denigration. Tale-bearing is bearing tales from house to house, from village to village, from district to district, [thinking] “So they will give to me out of fear of my bearing tales.” Backbiting is speaking censoriously behind another’s back after speaking kindly to his face; for this is like biting the flesh of another’s back, when he is not looking, on the part of one who is unable to look him in the face; therefore it is called backbiting. This is called belittling (nippesikatā) because it scrapes off (nippeseti), wipes off, the virtuous qualities of others as a bamboo scraper (veḷupesikā) does unguent, or because it is a pursuit of gain by grinding (nippiṃsitvā) and pulverizing others’ virtuous qualities, like the pursuit of perfume by grinding perfumed substances; that is why it is called belittling.

82. `In the description of pursuing gain with gain: pursuing is hunting after. Got from here is got from this house. There is into that house. Seeking is wanting. Seeking for is hunting after. Seeking out is hunting after again and again. [30] The story of the bhikkhu who went round giving away the alms he had got at first to children of families here and there and in the end got milk and gruel should be told here. Searching, etc., are synonyms for “seeking,” etc., and so the construction here should be understood thus: going in search of is seeking; searching for is seeking for; searching out is seeking out.

This is the meaning of scheming, and so on.

83. Now, [as regards the words] The evil states beginning with (§42): here the words beginning with should be understood to include the many evil states given in the Brahmajāla Sutta in the way beginning, “Or just as some worthy ascetics, while eating the food given by the faithful, make a living by wrong livelihood, by such low arts as these, that is to say, by palmistry, by fortune-telling, by divining omens, by interpreting dreams, marks on the body, holes gnawed by mice; by fire sacrifice, by spoon oblation …” (D I 9).

84. So this wrong livelihood entails the transgression of these six training precepts announced on account of livelihood, and it entails the evil states beginning with “Scheming, talking, hinting, belittling, pursuing gain with gain.” And so it is the abstinence from all sorts of wrong livelihood that is virtue of livelihood purification, the word-meaning of which is this: on account of it they live, thus it is livelihood. What is that? It is the effort consisting in the search for requisites. “Purification” is purifiedness. “Livelihood purification” is purification of livelihood.

85. (d) As regards the next kind called virtue concerning requisites, [here is the text: “Reflecting wisely, he uses the robe only for protection from cold, for protection from heat, for protection from contact with gadflies, flies, wind, burning and creeping things, and only for the purpose of concealing the private parts. Reflecting wisely, he uses alms food neither for amusement nor for intoxication nor for smartening nor for embellishment, but only for the endurance and continuance of this body, for the ending of discomfort, and for assisting the life of purity: ‘Thus I shall put a stop to old feelings and shall not arouse new feelings, and I shall be healthy and blameless and live in comfort.’ Reflecting wisely, he uses the resting place only for the purpose of protection from cold, for protection from heat, for protection from contact with gadflies, flies, wind, burning and creeping things, and only for the purpose of warding off the perils of climate and enjoying retreat. Reflecting wisely, he uses the requisite of medicine as cure for the sick only for protection from arisen hurtful feelings and for complete immunity from affliction” (M I 10). Herein, reflecting wisely is reflecting as the means and as the way;[21] by knowing, by reviewing, is the meaning. And here it is the reviewing stated in the way beginning, “For protection from cold” that should be understood as “reflecting wisely.”

86. Herein, the robe is any one of those beginning with the inner cloth. He uses: he employs; dresses in [as inner cloth], or puts on [as upper garment]. Only [31] is a phrase signifying invariability in the definition of a limit[22] of a purpose; the purpose in the meditator’s making use of the robes is that much only, namely, protection from cold, etc., not more than that. From cold: from any kind of cold arisen either through disturbance of elements internally or through change in temperature externally. For protection: for the purpose of warding off; for the purpose of eliminating it so that it may not arouse affliction in the body. For when the body is afflicted by cold, the distracted mind cannot be wisely exerted. That is why the Blessed One permitted the robe to be used for protection from cold. So in each instance, except that from heat means from the heat of fire, the origin of which should be understood as forest fires, and so on.

87. From contact with gadflies and flies, wind and burning and creeping things: here gadflies are flies that bite; they are also called “blind flies.” Flies are just flies. Wind is distinguished as that with dust and that without dust. Burning is burning of the sun. Creeping things are any long creatures such as snakes and so on that move by crawling. Contact with them is of two kinds: contact by being bitten and contact by being touched. And that does not worry him who sits with a robe on. So he uses it for the purpose of protection from such things.

88. Only: the word is repeated in order to define a subdivision of the invariable purpose; for the concealment of the private parts is an invariable purpose; the others are purposes periodically. Herein, private parts are any parts of the pudendum. For when a member is disclosed, conscience (hiri) is disturbed (kuppati), offended. It is called “private parts” (hirikopīna) because of the disturbance of conscience (hiri-kopana). For the purpose of concealing the private parts: for the purpose of the concealment of those private parts. [As well as the reading “hiriko-pīna-paṭicchādanatthaṃ] there is a reading “hirikopīnaṃ paṭicchādanatthaṃ.”

89. Alms food is any sort of food. For any sort of nutriment is called “alms food” (piṇḍapāta—lit. “lump-dropping”) because of its having been dropped (patitattā) into a bhikkhu’s bowl during his alms round (piṇḍolya). Or alms food (piṇḍapāta) is the dropping (pāta) of the lumps (piṇḍa); it is the concurrence (sannipāta), the collection, of alms (bhikkhā) obtained here and there, is what is meant.

Neither for amusement: neither for the purpose of amusement, as with village boys, etc.; for the sake of sport, is what is meant. Nor for intoxication: not for the purpose of intoxication, as with boxers, etc.; for the sake of intoxication with strength and for the sake of intoxication with manhood, is what is meant. [32] Nor for smartening: not for the purpose of smartening, as with royal concubines, courtesans, etc.; for the sake of plumpness in all the limbs, is what is meant. Nor for embellishment: not for the purpose of embellishment, as with actors, dancers, etc.; for the sake of a clear skin and complexion, is what is meant.

90. And here the clause neither for amusement is stated for the purpose of abandoning support for delusion; nor for intoxication is said for the purpose of abandoning support for hate; nor for smartening nor for embellishment is said for the purpose of abandoning support for greed. And neither for amusement nor for intoxication is said for the purpose of preventing the arising of fetters for oneself. Nor for smartening nor for embellishment is said for the purpose of preventing the arising of fetters for another. And the abandoning of both unwise practice and devotion to indulgence of sense pleasures should be understood as stated by these four. Only has the meaning already stated.

91. Of this body: of this material body consisting of the four great primaries. For the endurance: for the purpose of continued endurance. And continuance: for the purpose of not interrupting [life’s continued] occurrence, or for the purpose of endurance for a long time. He makes use of the alms food for the purpose of the endurance, for the purpose of the continuance, of the body, as the owner of an old house uses props for his house, and as a carter uses axle grease, not for the purpose of amusement, intoxication, smartening, and embellishment. Furthermore, endurance is a term for the life faculty. So what has been said as far as the words for the endurance and continuance of this body can be understood to mean: for the purpose of maintaining the occurrence of the life faculty in this body.

92. For the ending of discomfort: hunger is called “discomfort” in the sense of afflicting. He makes use of alms food for the purpose of ending that, like anointing a wound, like counteracting heat with cold, and so on. For assisting the life of purity: for the purpose of assisting the life of purity consisting in the whole dispensation and the life of purity consisting in the path. For while this [bhikkhu] is engaged in crossing the desert of existence by means of devotion to the three trainings depending on bodily strength whose necessary condition is the use of alms food, he makes use of it to assist the life of purity just as those seeking to cross the desert used their child’s flesh,[23] just as those seeking to cross a river use a raft, and just as those seeking to cross the ocean use a ship.

93. Thus I shall put a stop to old feelings and shall not arouse new feelings: [33] thus as a sick man uses medicine, he uses [alms food, thinking]: “By use of this alms food I shall put a stop to the old feeling of hunger, and I shall not arouse a new feeling by immoderate eating, like one of the [proverbial] brahmans, that is, one who eats till he has to be helped up by hand, or till his clothes will not meet, or till he rolls there [on the ground], or till crows can peck from his mouth, or until he vomits what he has eaten. Or alternatively, there is that which is called ‘old feelings’ because, being conditioned by former kamma, it arises now in dependence on unsuitable immoderate eating—I shall put a stop to that old feeling, forestalling its condition by suitable moderate eating. And there is that which is called ‘new feeling’ because it will arise in the future in dependence on the accumulation of kamma consisting in making improper use [of the requisite of alms food] now—I shall also not arouse that new feeling, avoiding by means of proper use the production of its root.” This is how the meaning should be understood here. What has been shown so far can be understood to include proper use [of requisites], abandoning of devotion to self-mortification, and not giving up lawful bliss (pleasure).

94. And I shall be healthy: “In this body, which exists in dependence on requisites, I shall, by moderate eating, have health called ‘long endurance’ since there will be no danger of severing the life faculty or interrupting the [continuity of the] postures.” [Reflecting] in this way, he makes use [of the alms food] as a sufferer from a chronic disease does of his medicine. And blameless and live in comfort (lit. “and have blamelessness and a comfortable abiding”): he makes use of them thinking: “I shall have blamelessness by avoiding improper search, acceptance and eating, and I shall have a comfortable abiding by moderate eating.” Or he does so thinking: “I shall have blamelessness due to absence of such faults as boredom, sloth, sleepiness, blame by the wise, etc., that have unseemly immoderate eating as their condition; and I shall have a comfortable abiding by producing bodily strength that has seemly moderate eating as its condition.” Or he does so thinking: “I shall have blamelessness by abandoning the pleasure of lying down, lolling and torpor, through refraining from eating as much as possible to stuff the belly; and I shall have a comfortable abiding by controlling the four postures through eating four or five mouthfuls less than the maximum.” For this is said:

With four or five lumps still to eat

Let him then end by drinking water;

For energetic bhikkhus’ needs

This should suffice to live in comfort (Th 983). [34]

Now, what has been shown at this point can be understood as discernment of purpose and practice of the middle way.

95. Resting place (senāsana): this is the bed (sena) and seat (āsana). For wherever one sleeps (seti), whether in a monastery or in a lean-to, etc., that is the bed (sena); wherever one seats oneself (āsati), sits (nisīdati), that is the seat (āsana). Both together are called “resting-place” (or “abode”—senāsana).

For the purpose of warding off the perils of climate and enjoying retreat: the climate itself in the sense of imperilling (parisahana) is “perils of climate” (utu-parissaya). Unsuitable climatic conditions that cause mental distraction due to bodily affliction can be warded off by making use of the resting place; it is for the purpose of warding off these and for the purpose of the pleasure of solitude, is what is meant. Of course, the warding off of the perils of climate is stated by [the phrase] “protection from cold,” etc., too; but, just as in the case of making use of the robes the concealment of the private parts is stated as an invariable purpose while the others are periodical [purposes], so here also this [last] should be understood as mentioned with reference to the invariable warding off of the perils of climate. Or alternatively, this “climate” of the kind stated is just climate; but “perils” are of two kinds: evident perils and concealed perils (see Nidd I 12). Herein, evident perils are lions, tigers, etc., while concealed perils are greed, hate, and so on. When a bhikkhu knows and reflects thus in making use of the kind of resting place where these [perils] do not, owing to unguarded doors and sight of unsuitable visible objects, etc., cause affliction, he can be understood as one who “reflecting wisely makes use of the resting place for the purpose of warding off the perils of climate.”

96. The requisite of medicine as cure for the sick: here “cure” (paccaya = going against) is in the sense of going against (pati-ayana) illness; in the sense of countering, is the meaning. This is a term for any suitable remedy. It is the medical man’s work (bhisakkassa kammaṃ) because it is permitted by him, thus it is medicine (bhesajja). Or the cure for the sick itself as medicine is “medicine as cure for the sick.” Any work of a medical man such as oil, honey, ghee, etc., that is suitable for one who is sick, is what is meant. A “requisite” (parikkhāra), however, in such passages as “It is well supplied with the requisites of a city” (A IV 106) is equipment; in such passages as “The chariot has the requisite of virtue, the axle of jhāna, the wheel of energy” (S V 6) [35] it is an ornament; in such passages as “The requisites for the life of one who has gone into homelessness that should be available” (M I 104), it is an accessory. But here both equipment and accessory are applicable. For that medicine as a cure for the sick is equipment for maintaining life because it protects by preventing the arising of affliction destructive to life; and it is an accessory too because it is an instrument for prolonging life. That is why it is called “requisite.” So it is medicine as cure for the sick and that is a requisite, thus it is a “requisite of medicine as cure for the sick.” [He makes use of] that requisite of medicine as cure for the sick; any requisite for life consisting of oil, honey, molasses, ghee, etc., that is allowed by a medical man as suitable for the sick, is what is meant.

97. From arisen: from born, become, produced. Hurtful: here “hurt (affliction)” is a disturbance of elements, and it is the leprosy, tumours, boils, etc., originated by that disturbance. Hurtful (veyyābādhika) because arisen in the form of hurt (byābādha). Feelings: painful feelings, feelings resulting from unprofitable kamma—from those hurtful feelings. For complete immunity from affliction: for complete freedom from pain; so that all that is painful is abandoned, is the meaning.

This is how this virtue concerning requisites should be understood. In brief its characteristic is the use of requisites after wise reflection. The word-meaning here is this: because breathing things go (ayanti), move, proceed, using [what they use] in dependence on these robes, etc., these robes, etc., are therefore called requisites (paccaya = ger. of paṭi + ayati); “concerning requisites” is concerning those requisites.

98. (a) So, in this fourfold virtue, Pātimokkha restraint has to be undertaken by means of faith. For that is accomplished by faith, since the announcing of training precepts is outside the disciples’ province; and the evidence here is the refusal of the request to [allow disciples to] announce training precepts (see Vin III 9–10). Having therefore undertaken through faith the training precepts without exception as announced, one should completely perfect them without regard for life. For this is said: [36]

“As a hen guards her eggs,

Or as a yak her tail,

Or like a darling child,

Or like an only eye—

So you who are engaged

Your virtue to protect,

Be prudent at all times

And ever scrupulous.” (Source untraced)

Also it is said further: “So too, sire, when a training precept for disciples is announced by me, my disciples do not transgress it even for the sake of life” (A IV 201).

99. And the story of the elders bound by robbers in the forest should be understood in this sense.

It seems that robbers in the Mahāvaṭṭanī Forest bound an elder with black creepers and made him lie down. While he lay there for seven days he augmented his insight, and after reaching the fruition of non-return, he died there and was reborn in the Brahmā-world. Also they bound another elder in Tambapaṇṇi Island (Sri Lanka) with string creepers and made him lie down. When a forest fire came and the creepers were not cut, he established insight and attained Nibbāna simultaneously with his death. When the Elder Abhaya, a preacher of the Dīgha Nikāya, passed by with five hundred bhikkhus, he saw [what had happened] and he had the elder’s body cremated and a shrine built. Therefore let other clansmen also:

Maintain the rules of conduct pure,

Renouncing life if there be need,

Rather than break virtue’s restraint

By the World’s Saviour decreed.

100. (b) And as Pātimokkha restraint is undertaken out of faith, so restraint of the sense faculties should be undertaken with mindfulness. For that is accomplished by mindfulness, because when the sense faculties’ functions are founded on mindfulness, there is no liability to invasion by covetousness and the rest. So, recollecting the Fire Discourse, which begins thus, “Better, bhikkhus, the extirpation of the eye faculty by a red-hot burning blazing glowing iron spike than the apprehension of signs in the particulars of visible objects cognizable by the eye” (S IV 168), this [restraint] should be properly undertaken by preventing with unremitting mindfulness any apprehension, in the objective fields consisting of visible data, etc., of any signs, etc., likely to encourage covetousness, etc., to invade consciousness occurring in connection with the eye door, and so on.

101. [37] When not undertaken thus, virtue of Pātimokkha restraint is unenduring: it does not last, like a crop not fenced in with branches. And it is raided by the robber defilements as a village with open gates is by thieves. And lust leaks into his mind as rain does into a badly-roofed house. For this is said:

“Among the visible objects, sounds, and smells,

And tastes, and tangibles, guard the faculties;

For when these doors are open and unguarded,

Then thieves will come and raid as’twere a village (?).And just as with an ill-roofed house

The rain comes leaking in, so too

Will lust come leaking in for sure

Upon an undeveloped mind” (Dhp 13).

102. When it is undertaken thus, virtue of Pātimokkha restraint is enduring: it lasts, like a crop well fenced in with branches. And it is not raided by the robber defilements, as a village with well-guarded gates is not by thieves. And lust does not leak into his mind, as rain does not into a well-roofed house. For this is said:

“Among the visible objects, sounds and smells,

And tastes and tangibles, guard the faculties;

For when these doors are closed and truly guarded,

Thieves will not come and raid as’twere a village (?).“And just as with a well-roofed house

No rain comes leaking in, so too

No lust comes leaking in for sure

Upon a well-developed mind” (Dhp 14).

103. This, however, is the teaching at its very highest.

This mind is called “quickly transformed” (A I 10), so restraint of the faculties should be undertaken by removing arisen lust with the contemplation of foulness, as was done by the Elder Vaṅgīsa soon after he had gone forth. [38]

As the elder was wandering for alms, it seems, soon after going forth, lust arose in him on seeing a woman. Thereupon he said to the venerable Ānanda:

“I am afire with sensual lust.

And burning flames consume my mind;

In pity tell me, Gotama,

How to extinguish it for good” (S I 188).

The elder said:

“You do perceive mistakenly,

That burning flames consume your mind.

Look for no sign of beauty there,

For that it is which leads to lust.

See foulness there and keep your mind

Harmoniously concentrated;

Formations see as alien,

As ill, not self, so this great lust

May be extinguished, and no more

Take fire thus ever and again” (S I 188).

The elder expelled his lust and then went on with his alms round.

104. Moreover, a bhikkhu who is fulfilling restraint of the faculties should be like the Elder Cittagutta resident in the Great Cave at Kuraṇḍaka, and like the Elder Mahā Mitta resident at the Great Monastery of Coraka.

105. In the Great Cave of Kuraṇḍaka, it seems, there was a lovely painting of the Renunciation of the Seven Buddhas. A number of bhikkhus wandering about among the dwellings saw the painting and said, “What a lovely painting, venerable sir!” The elder said: “For more than sixty years, friends, I have lived in the cave, and I did not know whether there was any painting there or not. Now, today, I know it through those who have eyes.” The elder, it seems, though he had lived there for so long, had never raised his eyes and looked up at the cave. And at the door of his cave there was a great ironwood tree. And the elder had never looked up at that either. He knew it was in flower when he saw its petals on the ground each year.

106. The king heard of the elder’s great virtues, and he sent for him three times, desiring to pay homage to him. When the elder did not go, he had the breasts of all the women with infants in the town bound and sealed off, [saying] “As long as the elder does not come let the children go without milk,” [39] Out of compassion for the children the elder went to Mahāgāma. When the king heard [that he had come, he said] “Go and bring the elder in. I shall take the precepts.” Having had him brought up into the inner palace, he paid homage to him and provided him with a meal. Then, saying, “Today, venerable sir, there is no opportunity. I shall take the precepts tomorrow,” he took the elder’s bowl. After following him for a little, he paid homage with the queen and turned back. As seven days went by thus, whether it was the king who paid homage or whether it was the queen, the elder said, “May the king be happy.”