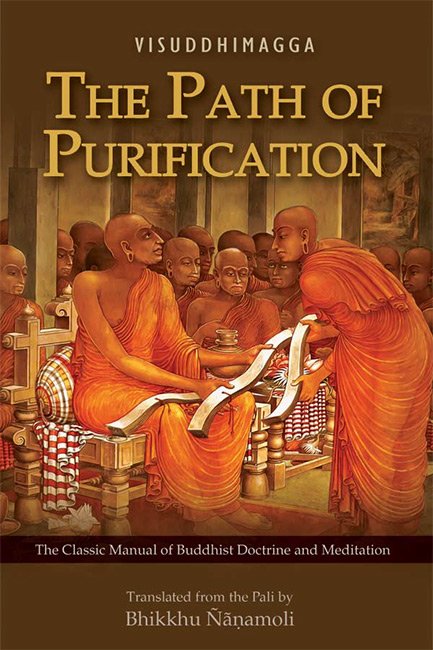

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

The English translation of the Visuddhimagga written by Buddhaghosa in the 5th Century. It contains the essence of the the teachings found in the Pali Tripitaka and represents, as a whole, an exhaustive meditation manual. The work consists of the three parts—1) Virtue (Sila), 2) Concentration (Samadhi) and 3) Understanding (Panna) covering twenty-t...

Background and Main Facts

The Visuddhimagga—here rendered Path of Purification—is perhaps unique in the literature of the world. It systematically summarizes and interprets the teaching of the Buddha contained in the Pali Tipiṭaka, which is now recognized in Europe as the oldest and most authentic record of the Buddha’s words. As the principal non-canonical authority of the Theravāda, it forms the hub of a complete and coherent method of exegesis of the Tipiṭaka, using the “Abhidhamma method” as it is called. And it sets out detailed practical instructions for developing purification of mind.

The works of Bhadantācariya Buddhaghosa fill more than thirty volumes in the Pali Text Society’s Latin-script edition; but what is known of the writer himself is meager enough for a page or two to contain the bare facts.

Before dealing with those facts, however, and in order that they may appear oriented, it is worth while first to digress a little by noting how Pali literature falls naturally into three main historical periods. The early or classical period, which may be called the First Period, begins with the Tipiṭaka itself in the 6th century BCE and ends with the Milindapañhā about five centuries later. These works, composed in India, were brought to Sri Lanka, where they were maintained in Pali but written about in Sinhalese. By the first century CE, Sanskrit (independently of the rise of Mahayana) or a vernacular had probably quite displaced Pali as the medium of study in all the Buddhist “schools” on the Indian mainland. Literary activity in Sri Lanka declined and, it seems, fell into virtual abeyance between CE 150 and 350, as will appear below. The first Pali renascence was under way in Sri Lanka and South India by about 400 and was made viable by Bhadantācariya Buddhaghosa. This can be called the Middle Period. Many of its principal figures were Indian. It developed in several centres in the South Indian mainland and spread to Burma, and it can be said to have lasted till about the 12th century. Meanwhile the renewed literary activity again declined in Sri Lanka till it was eclipsed by the disastrous invasion of Magha in the 11th century. The second renascence, or the Third Period as it may be termed, begins in the following century with Sri Lanka’s recovery, coinciding more or less with major political changes in Burma. In Sri Lanka it lasted for several centuries and in Burma for much longer, though India about that time or soon after lost all forms of Buddhism. But this period does not concern the present purpose and is only sketched in for the sake of perspective.

The recorded facts relating from the standpoint of Sri Lanka to the rise of the Middle Period are very few, and it is worthwhile tabling them.[1]

Why did Bhadantācariya Buddhaghosa come to Sri Lanka? And why did his work become famous beyond the island’s shores? The bare facts without some interpretation will hardly answer these questions. Certainly, any interpretation must be speculative; but if this is borne in mind, some attempt (without claim for originality) may perhaps be made on the following lines.

Up till the reign of King Vaṭṭagāmaṇi Abhaya in the first century BCE the Great Monastery, founded by Asoka’s son, the Arahant Mahinda, and hitherto without a rival for the royal favour, had preserved a reputation for the saintliness of its bhikkhus. The violent upsets in his reign followed by his founding of the Abhayagiri Monastery, its secession and schism, changed the whole situation at home. Sensing insecurity, the Great Monastery took the precaution to commit the Tipiṭaka for the first time to writing, doing so in the provinces away from the king’s presence. Now by about the end of the first century BCE (dates are very vague), with Sanskrit Buddhist literature just launching out upon its long era of magnificence, Sanskrit was on its way to become a language of international culture. In Sri Lanka the Great Monastery, already committed by tradition to strict orthodoxy based on Pali, had been confirmed in that attitude by the schism of its rival, which now began publicly to study the new ideas from India. In the first century BCE probably the influx of Sanskrit thought was still quite small, so that the Great Monastery could well maintain its name in Anurādhapura as the principal centre of learning by developing its ancient Tipiṭaka commentaries in Sinhalese. This might account for the shift of emphasis from practice to scholarship in King Vaṭṭagāmani’s reign. Evidence shows great activity in this latter field throughout the first century BCE, and all this material was doubtless written down too.

| KINGS OF CEYLON | RELEVANT EVENTS | REFS. |

| Devānampiya-Tissa: BCE 307–267 | Arrival in Sri Lanka of the Arahant Mahinda bringing Pali Tipiṭaka with Commentaries; Commentaries translated into Sinhalese; Great Monastery founded. | Mahāvaṃsa, Mhv XIII. |

| Duṭṭhagāmaṇi BCE 161–137 | Expulsion of invaders after 76 years of foreign occupation of capital; restoration of unity and independence. | Mhv XXV–XXXII |

| Many names of Great Monastery elders, noted in Commentaries for virtuous behaviour, traceable to this and following reign. | Adikaram, Early History of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, pp. 65–70 | |

| Vaṭṭagāmaṇi BCE 104–88 | Reign interrupted after 5 months by rebellion of Brahman Tissa, famine, invasion, and king’s exile. | Mhv XXXIII.33f. |

| Bhikkhus all disperse from Great Monastery to South SL and to India. | A-a I 92 | |

| Restoration of king after 14 years and return of bhikkhus. | Mhv XXXIII.78 | |

| Foundation of Abhayagiri Monastery by king. | Mhv XXXIII.81 | |

| Abhayagiri Monastery secedes from Great Monastery and becomes schismatic. | Mhv XXXIII.96 | |

| Committal by Great Monastery of Pali Tipiṭaka to writing for first time (away from royal capital). | Mhv XXXIII.100;

Nikāya-s (translation) 10–11 |

|

| Abhayagiri Monastery adopts

“Dhammaruci Nikāya of Vajjiputtaka Sect” of India. |

Nikāya-s 11 | |

| Meeting of Great Monastery bhikkhus decides that care of texts and preaching comes before practice of their contents. | A-a I 92f; EHBC 78 | |

| Many Great Monastery elders’ names noted in Commentaries for learning and contributions to decision of textual problems, traceable to this reign. | EHBC 76 | |

| Kuṭakaṇṇa Tissa BCE 30–33 | Many elders as last stated traceable to this reign too. | EHBC 80 |

| Last Sri Lanka elders’ names in Vinaya Parivāra (p. 2) traceable to this reign; Parivāra can thus have been completed by Great Monastery any time later, before 5th cent | EHBC 86 | |

| Bhātikābhaya BCE 20–CE 9 | Dispute between Great Monastery and Abhayagiri Monastery over Vinaya adjudged by Brahman Dīghakārāyana in favour of Great Monastery | Vin-a 582; EHBC 99 |

| Khanirājānu-Tissa 30–33 | 60 bhikkhus punished for treason. | Mhv XXXV.10 |

| Vasabha 66–110 | Last reign to be mentioned in body of Commentaries. | EHBC 3, 86–7 |

| Sinhalese Commentaries can have been closed at any time after this reign. | EHBC 3, 86–7 | |

| Gajabāhu I 113–135 | Abhayagiri Monastery supported by king and enlarged. | Mhv XXXV.119 |

| 6 kings 135–215 | Mentions of royal support for Great Monastery and Abhayagiri Monastery | Mhv XXXV.1, 7, 24, 33, 65 |

| Vohārika-Tissa 215–237 | King supports both monasteries. | |

| Abhayagiri Monastery has adopted Vetulya (Mahāyāna?) Piṭaka. | Nikāya-s 12 | |

| King suppresses Vetulya doctrines. | Mhv XXXVI.41 | |

| Vetulya books burnt and heretic bhikkhus disgraced | Nikāya-s 12 | |

| Corruption of bhikkhus by Vitaṇḍavadins (heretics or destructive critics). | Dīpavaṃsa XXII–XXIII | |

| Gothābhaya 254–267 | Great Monastery supported by king. | Mhv XXXVI.102 |

| 60 bhikkhus in Abhayagiri Monastery banished by king for upholding Vetulya doctrines. | Mhv XXXVI.111 | |

| Secession from Abhayagiri Monastery; new sect formed | Nikāya-s 13 | |

| Indian bhikkhu Saṅghamitta supports Abhayagiri Monastery | Mhv XXXVI.112 | |

| Jeṭṭha-Tissa 267–277 | King favours Great Monastery; Saṅghamitta flees to India. | Mhv XXXVI.123 |

| Mahāsena 277–304 | King protects Saṅghamitta, who returns. Persecution of Great Monastery; its bhikkhus driven from capital for 9 years. | Mhv XXXVII.1–50 |

| Saṅghamitta assassinated. |

Mhv XXXVII.27 |

|

| Restoration of Great Monastery | EHBC 92 | |

| Vetulya books burnt again. | EHBC 92 | |

| Dispute over Great Monastery boundary; bhikkhus again absent from Great Monastery for 9 months. | Mhv XXXVII.32 | |

| Siri Meghavaṇṇa 304–332 | King favours Great Monastery | EHBC 92; Mhv XXXVII.51f |

| Sinhalese monastery established at Buddha Gayā in India | Malalasekera PLC, p.68; Epigraphia Zeylanica iii, II | |

| Jeṭṭha-Tissa II 332–34 | Dīpavaṃsa composed in this period. | Quoted in Vin-a |

| Buddhadāsa 341–70 Upatissa 370–412 |

Also perhaps Mūlasikkhā and Khuddasikkhā (Vinaya summaries) and some of Buddhadatta Thera’s works. | PLC, p.77 |

| Mahānāma 412–434 | Bhadantācariya Buddhaghosa arrives in Sri Lanka. | Mhv XXXVII.215–46 |

| Samantapāsādikā (Vinaya commentary) begun in 20th and finished in 21st year of this king’s reign. | Vin-a Epilogue |

In the first century CE, Sanskrit Buddhism (“Hīnayāna,” and perhaps by then Mahāyāna) was growing rapidly and spreading abroad. The Abhayagiri Monastery would naturally have been busy studying and advocating some of these weighty developments while the Great Monastery had nothing new to offer: the rival was thus able, at some risk, to appear go-ahead and up-to-date while the old institution perhaps began to fall behind for want of new material, new inspiration and international connections, because its studies being restricted to the orthodox presentation in the Sinhalese language, it had already done what it could in developing Tipiṭaka learning (on the mainland Theravāda was doubtless deeper in the same predicament). Anyway we find that from the first century onwards its constructive scholarship dries up, and instead, with the reign of King Bhātika Abhaya (BCE 20–CE 9), public wrangles begin to break out between the two monasteries. This scene indeed drags on, gradually worsening through the next three centuries, almost bare as they are of illuminating information. King Vasabha’s reign (CE 66–110) seems to be the last mentioned in the Commentaries as we have them now, from which it may be assumed that soon afterwards they were closed (or no longer kept up), nothing further being added. Perhaps the Great Monastery, now living only on its past, was itself getting infected with heresies. But without speculating on the immediate reasons that induced it to let its chain of teachers lapse and to cease adding to its body of Sinhalese learning, it is enough to note that the situation went on deteriorating, further complicated by intrigues, till in Mahāsena’s reign (CE 277–304) things came to a head.

With the persecution of the Great Monastery given royal assent and the expulsion of its bhikkhus from the capital, the Abhayagiri Monastery enjoyed nine years of triumph. But the ancient institution rallied its supporters in the southern provinces and the king repented. The bhikkhus returned and the king restored the buildings, which had been stripped to adorn the rival. Still, the Great Monastery must have foreseen, after this affair, that unless it could successfully compete with Sanskrit it had small hope of holding its position. With that the only course open was to launch a drive for the rehabilitation of Pali—a drive to bring the study of that language up to a standard fit to compete with the “modern” Sanskrit in the field of international Buddhist culture: by cultivating Pali at home and abroad it could assure its position at home. It was a revolutionary project, involving the displacement of Sinhalese by Pali as the language for the study and discussion of Buddhist teachings, and the founding of a school of Pali literary composition. Earlier it would doubtless have been impracticable;but the atmosphere had changed. Though various Sanskrit non-Mahayana sects are well known to have continued to flourish all over India, there is almost nothing to show the status of the Pali language there by now. Only the Mahāvaṃsa [XXXVII.215f. quoted below] suggests that the Theravāda sect there had not only put aside but lost perhaps all of its old nonPiṭaka material dating from Asoka’s time.[2] One may guess that the pattern of things in Sri Lanka only echoed a process that had gone much further in India. But in the island of Sri Lanka the ancient body of learning, much of it pre-Asokan, had been kept lying by, as it were maturing in its two and a half centuries of neglect, and it had now acquired a new and great potential value due to the purity of its pedigree in contrast with the welter of new original thinking. Theravāda centres of learning on the mainland were also doubtless much interested and themselves anxious for help in a repristinization.[3] Without such cooperation there was little hope of success.

It is not known what was the first original Pali composition in this period; but the Dīpavaṃsa (dealing with historical evidence) belongs here (for it ends with Mahāsena’s reign and is quoted in the Samantapāsādikā), and quite possibly the Vimuttimagga (dealing with practice—see below) was another early attempt by the Great Monastery in this period (4th cent.) to reassert its supremacy through original Pali literary composition: there will have been others too.[4] Of course, much of this is very conjectural. Still it is plain enough that by 400 CE a movement had begun, not confined to Sri Lanka, and that the time was ripe for the crucial work, for a Pali recension of the Sinhalese Commentaries with their unique tradition. Only the right personality, able to handle it competently, was yet lacking. That personality appeared in the first quarter of the fifth century.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Exact dates are not agreed. The Sri Lanka Chronicles give the lengths of reigns of kings of Sri Lanka back to the time of the Buddha and also of kings of Magadha from Asoka back to the same time. Calculated backwards the list gives 543 BCE as the year of the Buddha’s parinibbāna (see list of kings in Codrington’s Short History of Ceylon, Macmillan 1947, p. xvi.). For adjustments to this calculation that bring the date of the parinibbāna forward to 483 BCE (the date most generally accepted in Europe), see e.g. Geiger, Mahāvaṃsa translation (introduction) Epigraphia Zeylanica I, 156; E. J. Thomas, Life of the Buddha, Kegan Paul, p. 26, n.1. It seems certain, however, that Mahānāma was reigning in the year 428 because of a letter sent by him to the Chinese court (Codrington p.29; E.Z. III, 12). If the adjusted date is accepted then 60 extra years have somehow to be squeezed out without displacing Mahānāma’s reign. Here the older date has been used.

[2]:

See also A Record of Buddhist Religion by I-tsing, translation by J. Takakusu, Claren do Press, 1896, p. xxiii, where a geographical distribution of various schools gives Mūlasarvāstivāda mainly in the north and Ariyasthavira mainly in the south of India. I-tsing, who did not visit Sri Lanka, was in India at the end of the 7th cent.; but he does not mention whether the Ariyasthavira (Theravāda) Nikāya in India pursued its studies in the Pali of its Tipiṭaka or in Sanskrit or in a local vernacular.

[3]:

In the epilogues and prologues of various works between the 5th and 12th centuries there is mention of e.g., Badaratittha (Vism-a prol.: near Chennai), Kañcipura (A-a epil.: = Conjevaram near Chennai), and other places where different teachers accepting the Great Monastery tradition lived and worked. See also Malalasekera, Pali Literature of Ceylon, p. 13; E.Z., IV, 69-71; Journal of Oriental Research, Madras, Vol. XIX, pp. 278f.

[4]:

Possibly the Vinaya summaries, Mūlasikkhā and Khuddasikkhā (though Geiger places these much later), as well as some works of Buddhadatta Thera. It has not been satisfactorily explained why the Mahāvaṃsa, composed in the late 4th or early 5th cent., ends abruptly in the middle of Chapter 37 with Mahāsena’s reign (the Chronicle being only resumed eight centuries later).