The Dawn of the Dhamma

Illuminations from the Buddha’s First Discourse

by Sucitto Bhikkhu | 76,370 words

Dedication: May all beings live happily, free from fear, and may all share in the blessings springing from the good that has been done....

Chapter 11 - Realization

Idam dukkhanirodho … cakkhum udapadi nanam udapadi panna udapadi vijja udapadi aloko udapadi

Idam dukkhanirodho … cakkhum udapadi nanam udapadi panna udapadi vijja udapadi aloko udapadi

There is this Noble Truth of the Cessation of Suffering: …

This Noble Truth must be penetrated to by realizing the Cessation of Suffering: …

This Noble Truth has been penetrated to by realizing the Cessation of Suffering:

such was the vision, insight, wisdom, knowing and light that arose in me about things not heard before.

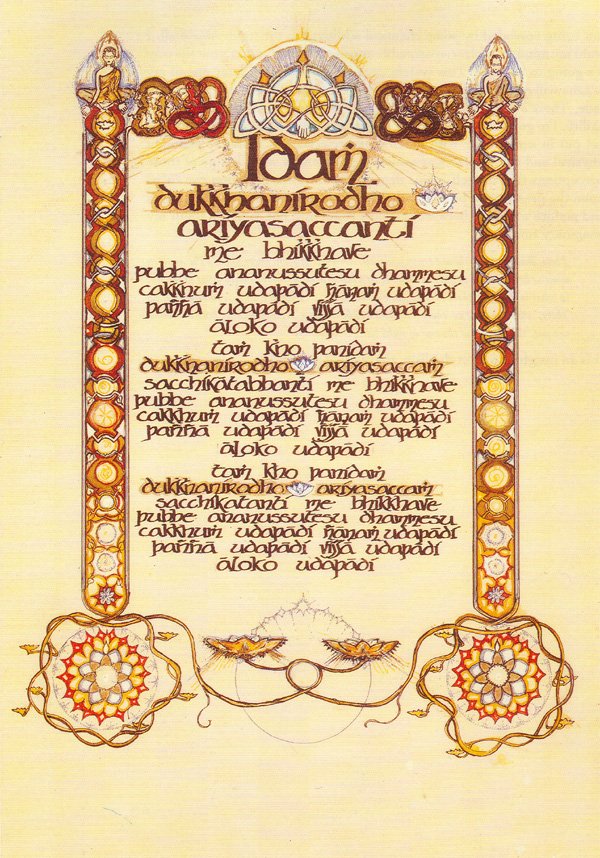

Here the Buddha talks about realization; making the spiritual ideal of Ultimate Peace real. The images in the top of these paintings have been developing progressively from the first one of a closed in frame of knotwork. Here, the twin coiling forms of ignorance and desire are separate from the central interweave at the top. In the first picture of this sequence, the central interweave at the top was the tangle of self view with its twin heads of ignorance and desire. In this picture of realization, the energies that support self view have undergone some changes. Now, within the interweave, the radiance of true being and the earth touching hand of Tathagatas confirming Suchness appear.

In the upper corners, the serpents have been replaced by Awakened Ones whose arms are spreading out to send forth Truth and to open to the world of circumstance. The knotwork of the borders has become a setting for images of light and purity. It culminates in the two lower corners where a six flowered loop (of the purified sense consciousness) is centered on a motif that represents the radiance of enlightenment. In the center, two more flowers represent wisdom and compassion—the two aspects of Buddhas that are not really separable. The thin blue circle, a simple line around an empty space, represents the abiding of Tathagatas, suggestive of the clarity of form and the spaciousness of not self, in perfect balance.

In some ways the Noble Truths are mundane and in some ways supramundane. Remember that mundane doesn"t mean worldly but the dualistic sense of oneself operating in the world. Consider then, what is the essence of this mundane understanding? Herein, one recognizes that the self centered appetite for things to have, to control or to become is not appeased through gratification. This is the First Truth. Consequently, it is the very need and hankering for gratifying experiences and irritation with what we find disagreeable that are the source of our suffering. From this we develop insight into the Second Truth. Then we understand the Third Truth—part of the solution is found in simplifying one"s needs and expectations, and learning to appreciate one"s innate sense of being. If we are scrupulous with the ethical side of our life, the mind is freed from remorse and negativity. Meditation helps us to calm down and be more centered, and we begin to experience the fullness of the Fourth Truth. This is the experience of the Four Noble Truths on a mundane level.

As we grow more attuned to the need for full awareness, a natural sensitivity arises allowing the delight and joy of simple things to leave a greater impact. Cultivating loving kindness and patience are also intrinsic features of the Way out of Suffering. By such means, we no longer bring problems into the world or into our own minds, and we generate good kamma, many blessings and skills. This is what is called a deliverance in terms of time. It has to be realized, activated and made real. It is not enough to theorize about it. And it has to be worked at individually by all of us for ourselves, with our own habits, weaknesses and strengths.

However, deliverance in terms of time is also temporary. One of the major difficulties is that our habits are often very strong, and it seems that they never relent. Just refraining from appeasing self centered appetites does not make the appetite die down; in fact “withdrawal symptoms” can stimulate them all the more. Just when things seem to be settling down nicely, old habits suddenly reappear.

Life as a bhikkhu is a good example of what I mean because it heightens and projects the complexity of the problem. This life style involves a good deal of limitation on activity and sensory experience. But it"s not just a question of moral conduct—like refraining from lying or aggressive activity or sexual infidelity (which are good moral standards for people in the world). Bhikkhu life is also the enactment of an ethical norm as a foundation for reflection—for oneself and others. When I became a bhikkhu, I didn"t know all the reasons for doing so, it just seemed right at the time: to practice meditation and live in a peaceful environment. So I took the opportunity to live in a situation that was conducive to Dhamma, where I could stay as long as I liked with adequate accommodation and food. It wasn"t five star, but I didn"t go to the monastery for the food or lodging, or to have personal relationships, and entertainment. I"d done all that stuff and not been content. And now, having been given the opportunity to practice and hear the teachings with adequate support, I felt a sense of honor to fit in with the system and not disrespect it. And anyway, I thought I"d probably get what I needed from the practice quite soon and then I could go back to doing things in the normal way, according to my tastes.

Life as a bhikkhu is a good example of what I mean because it heightens and projects the complexity of the problem. This life style involves a good deal of limitation on activity and sensory experience. But it"s not just a question of moral conduct—like refraining from lying or aggressive activity or sexual infidelity (which are good moral standards for people in the world). Bhikkhu life is also the enactment of an ethical norm as a foundation for reflection—for oneself and others. When I became a bhikkhu, I didn"t know all the reasons for doing so, it just seemed right at the time: to practice meditation and live in a peaceful environment. So I took the opportunity to live in a situation that was conducive to Dhamma, where I could stay as long as I liked with adequate accommodation and food. It wasn"t five star, but I didn"t go to the monastery for the food or lodging, or to have personal relationships, and entertainment. I"d done all that stuff and not been content. And now, having been given the opportunity to practice and hear the teachings with adequate support, I felt a sense of honor to fit in with the system and not disrespect it. And anyway, I thought I"d probably get what I needed from the practice quite soon and then I could go back to doing things in the normal way, according to my tastes.

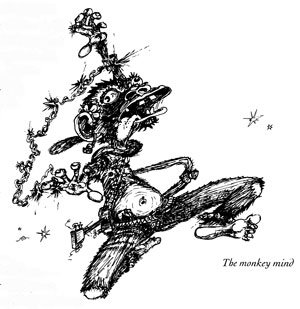

As the weeks passed, I began to settle in. My ability to concentrate improved quite a bit, but thoughts started to drift through … I wondered how long I should sit, whether or not to move when the body hurt (to be sensitive) or maybe to sit it out (and be resolute).

- … Sensitive or resolute, which is better? Maybe I"ll endure for a while, and eventually build up a greater ability to tolerate pain

- … but it would be nice not to have it, and it"s natural not to want pain

- … whoops, better get back to concentrating on the breath, the mind is wandering

- … not as good as yesterday

- … temporary setback

- … resolution

- … Breathing in

- … note the sensation in the abdomen

- … breathing out

- … flowing out through the nostrils

- … Wonder how long before you don"t feel pain?

- … It would be nice to go for a walk now, stretch the legs, I could do that mindfully, yes

- … but that"s giving in, you sneak!

- … Maintain discipline

- … one hour sitting, one hour walking

- … wearing out the forces of desire

- … How long does this go on for?

- … It"s half an hour since I sat down

- … evening, dinner time, cooking smells in the lane

- …normal people are enjoying themselves doing normal, blameless things like having a meal, pleasant company, nothing wild or crazy

- … yes, when I get out of here I"ll be much more restrained, I"ve learned my lesson

- … no more wild scenes

- … and

- … what was her name? She was a lot of fun really, despite the temper

- … and

- … whoa! If it was all so great, why did you leave it! Mindfulness to the rescue again! Resolution

- … get back to the breath

- … breathing out

- … amazing how far your mind can travel in a matter of seconds

- … scientists reckon that the alpha rhythms of the brain travel at

- … how many cycles per second?

- … Maybe I could do this whole thing much easier with a biofeedback machine; definite improvement on these primitive Asian meditation techniques

- … one flicker away from samadhi and you get a bleep! Maybe when I get back to England

- … now SHUT UP! That"s it, cutting through delusion

- … breathing in

- … breathing out, here and now

- … easy now

- … lighten up on the thinking, just bare awareness

- … like a naked ascetic: bare awareness, good one that, eh? It"d be nice to live on a tropical beach where you didn"t have to wear clothes

- … Goa

- … done that too

- … what"s the point?

- … Get down to it! Right, half an hour more and I"11 call it quits for the day, give myself a little treat

- … like what! I guess I could walk round the hut and look at the moon

- … Big deal!

- … Easy now, “Nibbana is the highest happiness,” here and now, open to the moment

- … don"t repress

- … That"s better, flowing along real smooth

- … you don"t have to live as a monk to do this, it"s just non attachment, living with a smile

- … Taoism"s the answer really, then you can have music, sex in a non attached way

- … Who are you kidding! Breathing in

- … then long slow breath out, deep and slow

- … nice, and only twenty five minutes left

- … God, my knees hurt! How long does this go on for?

It"s the real thing, all right. I suppose one of the benefits of living in a Buddhist monastery -and one of the torments- is that you have the example of the Buddha, and generally other living beings with some easeful, loving and wise qualities. And you realize what a blessing a skillful life is to the world compared to just following selfish desires. The benefit is that you feel it must be possible to work this dukkha out in a way that is not brutal or repressive; the torment is not being able to find that in yourself. At a certain point, the Path out of suffering seems to take you back into it again. Calm, and the understanding that following desire is not reliable, together produce all kinds of conflicts with one"s habits. That conflict seems to create as much dukkha as blindly following one"s desires. Then something has to shift.

For this you have to go beyond self view, and develop the supramundane Path. What happens is that you begin to look at your dukkha in an impersonal way. It"s true, different people have different mind stuff to work with, but essentially there comes about a realization that the core of the feeling of dukkha comes from something we all do: we take things personally. And you can"t stop taking things personally just as an idea. The practice involves cessation, letting go of “self” through directly knowing “self.” This must occur by feeling out and examining some pretty well established positions. “I"m going to do it” is one of them; “I can"t do it” is another; and the list goes on through every kind of self view about “I"m not worthy/good enough,” “It"s not good enough for me,” “I have a lot of kamma to work out,” and “I have to get rid of self.”

In the course of practice, all these self views come and go continuously until, gradually, the realization of their impermanence begins to sink in. The practice is one of sustaining that attention and that realization. When the habits of mind discharge all these views, if one can keep to a straight forward, non fanatical, steady practice and not cop out into some philosophical attitude about it all, the Way begins to take shape on its own. The Way is not self, it is not made by controlling the mind through the will.

Of course, the Way is born out of personal effort, but it is effort of a particular kind—the effort to be mindful. For supramundane freedom, mindfulness is directed towards what we term “self”—in ourselves. The practice that is central to the supramundane Path is called satipatthana, “The Foundations of Mindfulness,” described in detail by the Buddha in two Suttas of that name (e.g., Digha Nikaya: Sutta 22). One of the essential and repeated expressions of this cultivation is a “knowing” that is non dualistic. For example, “contemplating body as body;” “when walking, he knows he is walking;” “knowing feelings in the feelings.” Furthermore, one is encouraged to know: “a hating mind as hating;” “a deluded mind as deluded;” “a developed mind as developed;” “an unsurpassed mind as unsurpassed.” Even the hindrances are to be contemplated in this non judgemental way—noticing greed, hatred, dullness, restlessness and worry, when they are present, under what conditions they arise, how they can be abandoned and the way that prevents them from arising.

This brings us back to the same mental mode as with the contemplation of the Four Noble Truths; an almost disquieting serenity with what surely should arouse our passions. The pragmatic contemplative recognizes that it"s natural enough to have strong feelings, but they don"t solve the problem. And it"s not that one isn"t doing something about it by meditating—the “knowing it as it is” approach requires a keen attention, but in the quickness to follow the moment as it is, there is no comment being made. The monologue of self which normally attends our actions and thoughts like the audience in a theater, alternately hissing and booing at the villains and cheering the heroes, is steadily reduced each time that we bring the mind back to the object of contemplation. The theater empties. And the mind begins to notice the silence and abide more in that. Energy is withdrawn from the proliferation of feelings and perceptions around mental and physical objects and the hindrances fade out. When there is attention without self conscious concern over the mind, the mind begins to clear in a light and peaceful way.

The watchfulness or “knowingness” becomes a common factor of experience. It can be present in any circumstance and it can be directed to cover each moment of experience. So in one way, it is timeless and beyond circumstance. Its fleeting nature is actually our fleeting attention to it—mainly because we"re not always interested in being Awake. Being Awake doesn"t usually seem so important—until, of course, you feel dukkha.

Those who endeavor to practice begin to experience a dispassion behind the movements of mind. The practice is sustained through realizing the dukkha of any position held as self. One comes to see that the dispassion has always been there, only it wasn"t realized. After the love and the despair and the tears and the excitement, one always comes back to the knowing. We tend to practice from the unenlightened position of: “I"m doing it. I"m going to develop, improve, get rid of, be wise, be more of this and less of that.” Self view leads to becoming which brings us to more dukkha. All these attitudes can free us from selfishness, but ultimately their value is that they bring the real problem and the Way more clearly into awareness. The supramundane Path begins with the priceless realization that “there is dukkha” which is unavoidably bound up with the sense of self. For ultimate deliverance, to have really known what the experience of self view is, the mundane Path is a necessary prologue.

It takes some skill to get past the desire for attainment, but in searching for that Truth that is unconditioned, not supported by circumstances, we can know when we are still holding on. You"ll notice that even attainment of refined conditions is unsatisfactory. There is a story of Venerable Anuruddha, a renowned bhikkhu, who sought the advice of the Arahant Sariputta. Anuruddha had developed some remarkable qualities which he described to Sariputta: he had the “divine eye” with which he could see the ten thousandfold world system, he had great energy and resolute mindfulness; yet, he said, his heart was not at peace. Venerable Sariputta replied:

Well, Anuruddha, as to your statement about seeing the ten thousandfold world system, that is just your conceit. Ad to your statement about being strenuous and unshaken and so forth, that is just arrogance. As to your statement about your heart not being released … that is just worrying. It would indeed be well for the Venerable Anuruddha if he were to abandon these three conditions, if he were not to think about them, but were to focus his mind on the Deathless element.

(Anguttara Nikaya: [ 1 ], Ones, 281)

So what and where is “the Deathless element?” Well the only thing that does not pass away is that which does not arise. This is difficult to describe. But one can talk about that Wakefulness, that knowing itself that the Buddha encourages us not to become, not to achieve or add to, but to realize. It has always been here, but we have been using it in the wrong way. We have been using the awareness of the mind to seek out and create perceptions and feelings that foster our sense of being a separate identity. All that arises and ceases is born and dies. But the “knowing” of it does not. An untrained mind will attend to the objects of knowing—that which arises and ceases; a learner will be strengthening the power of the knowing; an adept will be proficient at focusing on that “Deathless element.” Realization awakens to the Truth that has been caught in that process. Then one is not bound to reacting in compulsive identity habits.

When we cease to activate these habits, the mind experiences real, complete, ordinary peace. One comes to recognize that a liberated life is just a matter of sustaining the perspective of not self in the silences and bustles, the pains and the pleasures, the successes and the confusions of life. Ultimate deliverance, then, is not bound to time nor outside of it. In order for cessation to be ever present, it has to be a way of living that goes beyond the self view. It is a Noble Path because it has to be selfless.