Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Jatila the Brahmin which is verse 393 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 393 is part of the Brāhmaṇa Vagga (The Brāhmaṇa) and the moral of the story is “’Tis not matted hair nor birth nor family, but truth and Dhamma which make a brahmin true”.

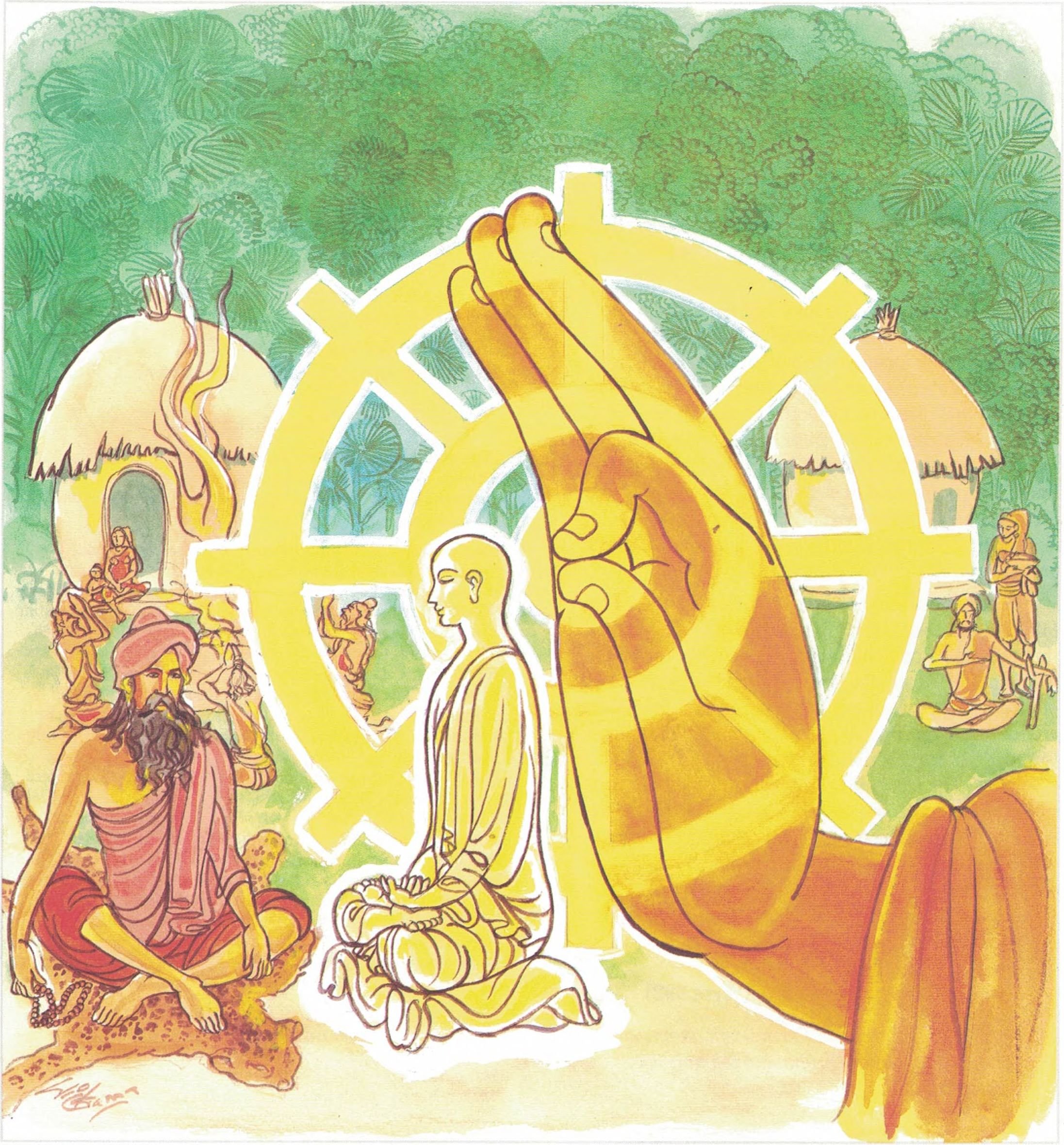

Verse 393 - The Story of Jaṭila the Brāhmin

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 393:

na jaṭāhi na gottena na jaccā hoti brāhmaṇo |

yamhi saccañ ca dhammo ca so sucī so ca brāhmaṇo || 393 ||

393. By birth one is no brahmin, by family, austerity. In whom are truth and Dhamma too pure is he, a Brahmin’s he.

’Tis not matted hair nor birth nor family, but truth and Dhamma which make a brahmin true. |

The Story of Jaṭila the Brāhmin

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to Jaṭila, a brāhmin ascetic who wore matted hair.

The story goes that this brāhmin said one day to himself, “I am well born on my mother’s side and on my father’s side, for I was reborn in the family of a brāhmin. Now the monk Gotama calls his own disciples brāhmins. He ought to apply the same title to me too.” So the brāhmin went to the Buddha and asked him about the matter. Said the Buddha to the brāhmin, “Brāhmin, I do not call a man a brāhmin merely because he wears matted locks, merely because of his birth and lineage. But he that has penetrated the truth, him alone do I call a brāhmin.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 393)

jaṭāhi brāhmaṇo na hoti gottena brāhmaṇo na hoti jaccā brāhmaṇo

na hoti yamhi saccañca dhammo ca so sucī so ca brāhmaṇo

jaṭāhi: because of the matted hair; brāhmaṇo na hoti: one does not become a brāhmaṇa; gottena: by clan; brāhmaṇo na hoti: one does not become a brāhmaṇa; jaccā: because of birth; brāhmaṇo na hoti: one does not become a brāhmaṇa; yamhi in a person; saccaṃ [sacca]: awareness of truth;dhammo ca: and spiritual reality (exist); so sucī: if he is pure; so ca brāhmaṇo [brāhmaṇa]: he is the true brāhmin

One does not become a brāhmin by one’s matted hair. Nor does one become a brāhmin by one’s clan. Even one’s birth will not make a brāhmin. If one has realized the Truth, has acquired the knowledge of the Teaching, if he is also pure, it is such a person that I describe as a brāhmin.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 393)

na jaccā hoti Brāhmāno: one does not become a brāhmaṇa merely by birth. This statement represents the Buddha’s revolutionary philosophy which disturbed the brāhmin-dominated upper crust of Indian society. The brāhmins of the day considered themselves the chosen of Brahma, and that by birth they deserved veneration by all others. Buddha dealt a blow to this entrenched concept.

Society at that time was divided into four sections called varṇas. It is clear that the Teachings of this great teacher denounced this varṇa or caste system. Indian society of that time especially benefitted from the doctrines of the Buddha because it was the first time that the rigid system of casteism was denounced. It would appear that the people of India, steeped in ignorance, received great consolation from this new doctrine of the Buddha. Owing to this important fact the great transcendental doctrine of the Buddha began to spread throughout all India.

There is a great store of varied information contained in the Buddhist literature of the Tripitaka concerning the complex society of Jambudīpa during the 6th Century B.C., when the Buddha lived and when many philosophies were expounded. Founders of different religions and philosophies preached diverse ways of salvation to be followed by human beings. The intelligentsia engaged themselves in the search to discover which of these proclaimed the truth.

The Buddhist system of thought provides an ethical realism in which the nature of the traditional social structure could be critically examined. Prior to the Buddha high spiritual pursuits were allowed only to privileged groups. But the Buddha opened the path of Enlightenment to all who had the potential to achieve spiritual liberation.

Since this was an assault on the entrenched system, many a brāhmin was provoked into entering into arguments with the Buddha about who a real brāhmin was. This verse arose from one such encounter.