Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Venerable Sariputta which is verse 389-390 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 389-390 is part of the Brāhmaṇa Vagga (The Brāhmaṇa) and the moral of the story is “Strike not a brahmin, nor violently react. Shame on the former, the latter much worse” (first part only).

Verse 389-390 - The Story of Venerable Sāriputta

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 389-390:

na brāhmaṇassa pahareyya nā'ssa muñcetha brāhmaṇo |

dhī brāhmaṇassa hantāraṃ tato dhī yassa muñcati || 389 ||

na brāhmaṇass'etad'akiñci seyyo yadā nisedho manaso piyehi |

yato yato hiṃsamano nivattati tato tato sammatieva dukkhaṃ || 390 ||

389. One should not a Brahmin beat nor for that would He react. Shame! Who would a Brahmin beat, more shame for any should they react.

390. For brahmin no small benefit when mind’s aloof from what is dear. As much he turns away from harm so much indeed does dukkha die.

Strike not a brahmin, nor violently react. Shame on the former, the latter much worse. |

Eschew things dear.’Tis triumph for a monk. Abstain from violence.’Tis pain at its end. |

The Story of Venerable Sāriputta

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses with reference to Venerable Sāriputta.

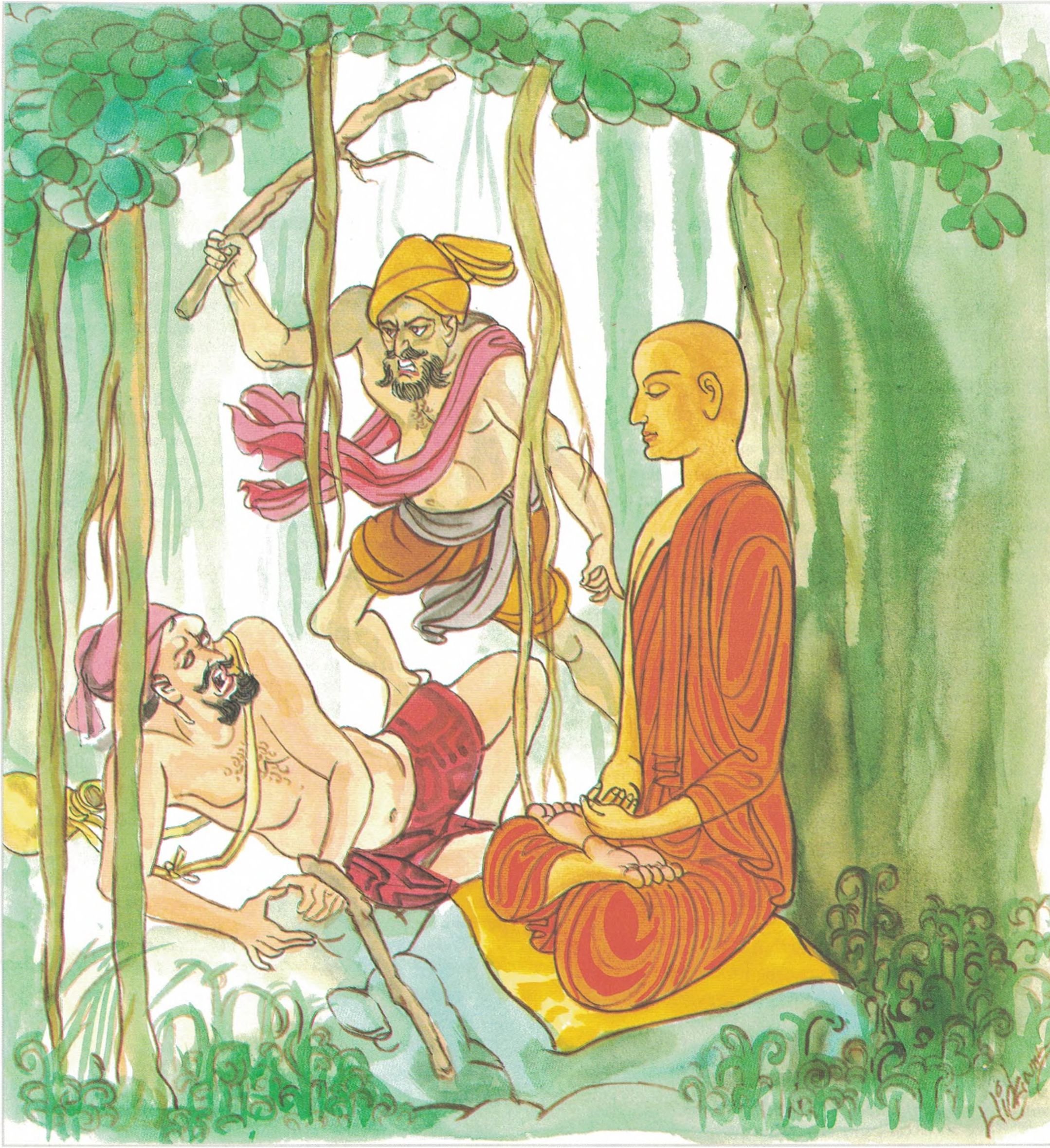

The story goes that once upon a time several men gathered together at a certain place and rehearsed the noble qualities of the Venerable, saying, “Oh, our noble master is endowed with patience to such a degree that even when men abuse him and strike him, he never gets the least bit angry!” Thereupon a certain brāhmin who held false views asked, “Who is this that never gets angry?” “Our Venerable.” “It must be that nobody ever provoked him to anger.” “That is not the case, brāhmin.” “Well then, I will provoke him to anger.” “Provoke him to anger if you can!” “Trust me!” said the brāhmin; “I know just what to do to him.”

Just then the Venerable entered the city for alms. When the brāhmin saw him, he stepped up behind him and struck him a tremendous blow with his fist in the back. “What was that?” said the Venerable, and without so much as turning around to took, continued on his way. The fire of remorse sprang up within every part of the brāhmin’s body. “Oh, how noble are the qualities with which the Venerable is endowed!” exclaimed the brāhmin. And prostrating himself at the Venerable’s feet, he said, “Pardon me, Venerable.” “What do you mean?” asked the Venerable. “I wanted to try your patience and struck you.” “Very well, I pardon you.” “If, Venerable, you are willing to pardon me, hereafter sit and receive your food only in my house.” So saying, the brāhmin took the Venerable’s bowl, the Venerable yielding it willingly, and conducting him to his house, served him with food.

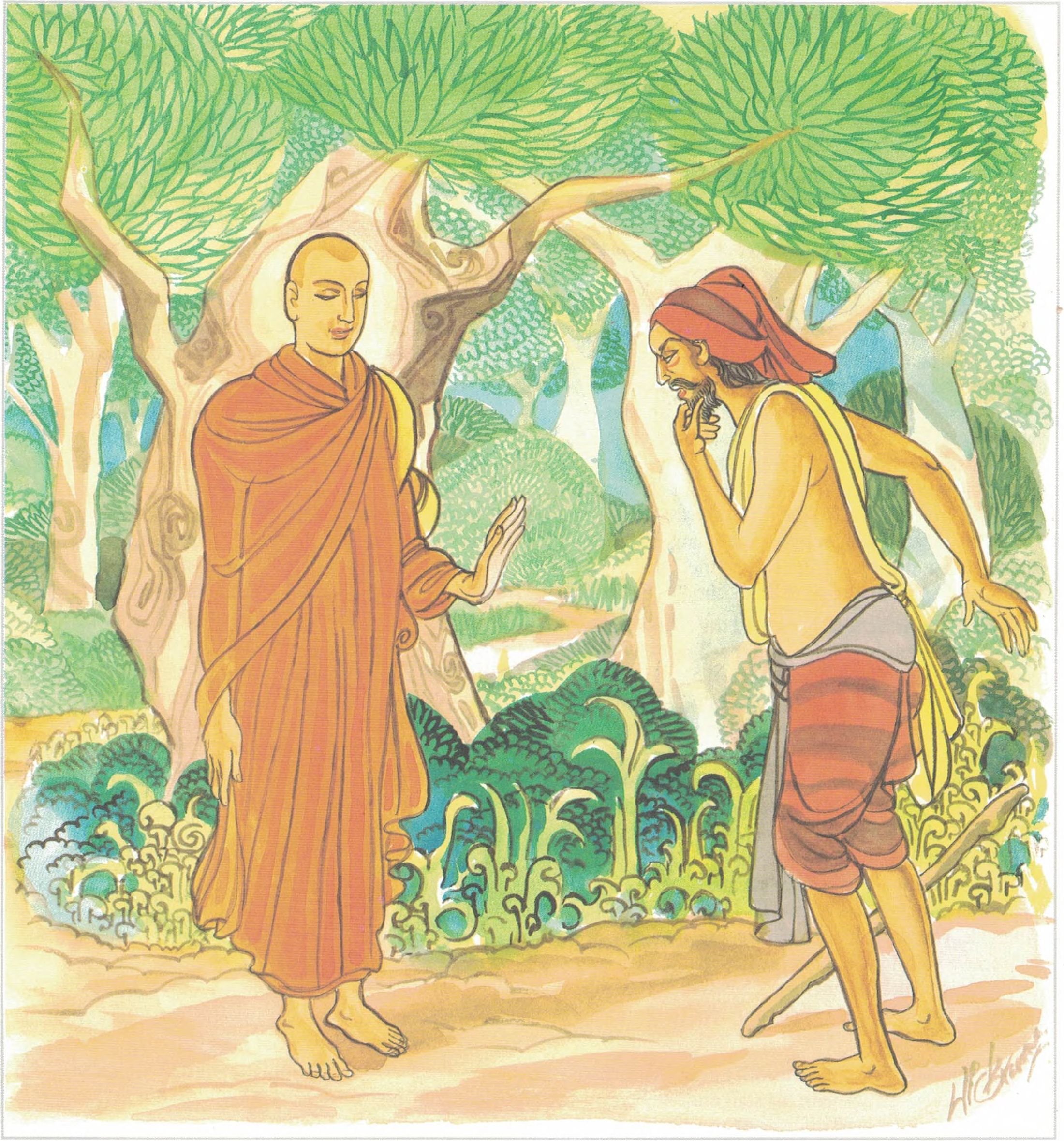

The bystanders were filled with anger. “This fellow,” said they, “struck with his staff our noble Venerable, who is free from all offense; he must not be allowed to get away; we will kill him right here and now.” And taking clods of earth and sticks and stones into their hands, they stood waiting at the door of the brāhmin’s house. As the Venerable rose from his seat to go, he placed his bowl in the hand of the brāhmin. When the bystanders saw the brāhmin going out with the Venerable, they said, “Venerable, order this brāhmin who has taken your bowl to turn back.” “What do you mean, lay disciples?” “That brāhmin struck you and we are going to do for him after his deserts.” “What do you mean? Did he strike you or me?” “You, Venerable.” “If he struck me, he begged my pardon; go your way.” So saying, he dismissed the bystanders, and permitting the brāhmin to turn back, the Venerable went back again to the monastery.

The monks were highly offended. ‘What sort of thing is this!” they exclaimed; “a brāhmin struck the Venerable Sāriputta a blow, and the Venerable straightaway went back to the house of the very brāhmin who struck him and accepted food at his hands! From the moment he struck the Venerable, for whom will he any longer have any respect?” He will go about pounding everybody right and left.” At that moment the Buddha drew near. “Monks,” said He, “what is the subject that engages your attention now as you sit here all gathered together?” “This was the subject we were discussing.” Said the Buddha, “Monks, no brāhmin ever strikes another brāhmin; it must have been a householder-brāhmin who struck a monk-brāhmin; for when a man attains the fruit of the third path, all anger is utterly destroyed in him.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 389)

brāhmaṇassa na pahareyya brāhmaṇo assa na muñcetha

brāhmaṇassa hantāraṃ dhī yassa muñcati tato dhī

brāhmaṇassa: a brāhmaṇa; na pahareyya: do not attack; assa: towards the one who attacks him; na muñcetha: should not have hatred; brāhmaṇassa hantāraṃ dhī: I condemn him who attacks a brāhmin; yassa muñcati: he who gets angry; tato dhī: the more I condemn

No one should strike a brāhmaṇa–the pure saint. The brāhmaṇa who has become the victim must refrain from attacking the attacker in return, or show anger in return. Shame on him who attacks a brāhmaṇa; greater shame on him who displays retaliatory anger.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 390)

etaṃ brāhmaṇassa na kiñci seyyo yadā manaso piyehi (yo) nisedho

yato hiṃsamāno nivattati tato tato dukkhaṃ sammatimeva

brāhmaṇassa: of the brāhmaṇa; akiñci seyyo na: not at all a small asset; yadā: if, etaṃ: this (non-retaliation); manaso [manasa]: in the mind of him who hates; piyehi: pleasant; nisedho [nisedha]: a thought free of ill-will occurs; yato yato: for some reason; hiṃsamāno [hiṃsamāna]: the violent mind; nivattati: ceases; tato tato: in these instances; dukkhaṃ [dukkha]: pain; sammatimeva: surely subsides To the brāhmaṇa, the act of not returning hate is not a minor asset–it is a great asset, indeed. If in a mind usually taking delight in hateful acts, there is a change for the better, it is not a minor victory. Each time the violent mind ceases, suffering, too, subsides.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 389-390)

hiṃsamāno nivattati: intent to harm ceases. These stanzas are primarily concerned with the need to be compassionate, even to those who adopt an aggressive attitude to one. In the Buddhist system four noble virtues are advocated to counter aggressive behaviour. These four virtues are described as Brahma Vihāra. This could be rendered as Sublime Attitudes. These four attitudes are loving-kindness (mettā), compassion (karunā), appreciative joy (muditā) and equanimity (upekkhā). All these four virtues curb aggressive, unfriendly behaviour and on the positive side promote non-violence, affection, kindness, compassion and sympathy. Of these four, loving-kindness (mettā) is first.

The second virtue that sublimates man is compassion (karunā). It is defined as that which makes the hearts of the good quiver when others are subject to suffering, or that which dissipates the sufferings of others. Its chief characteristic is the wish to remove the woes of others.

The hearts of compassionate persons are even softer than flowers. They do not and cannot rest satisfied until they relieve the sufferings of others. At times, they even go to the extent of sacrificing their lives so as to alleviate the sufferings of others. The story of the Vyāghri Jātaka where the Bodhisatta sacrificed his life to save a starving tigress and her cubs may be cited as an example.

It is compassion that compels one to serve others with altruistic motives. A truly compassionate person lives not for himself but for others. He seeks opportunities to serve others expecting nothing in return, not even gratitude.

Many amidst us deserve our compassion. The poor and the needy, the sick and the helpless, the lonely and the destitute, the ignorant and the vicious, the impure and the undisciplined are some that demand the compassion of kind-hearted, noble-minded men and women, to whatever religion or to whatever race they belong.

Some countries are materially rich but spiritually poor, while some others spiritually rich but materially poor. Both of these pathetic conditions have to be taken into consideration by the materially rich and the spiritually rich.

It is the paramount duty of the wealthy to come to the succor of the poor, who unfortunately lack most of the necessities of life.

Surely those who have in abundance can give to the poor and the needy their surplus without inconveniencing themselves.

Once, a young student removed the door curtain in his house and gave it to a poor person telling his good mother that the door does not feel the cold but the poor certainly do. Such a kind-hearted attitude in young men and women is highly commendable.

It is gratifying to note that some wealthy countries have formed themselves into various philanthropic bodies to help under-developed countries, especially in Jambudīpa, in every possible way.

Charitable organizations have also been established in all countries by men, women and students to give every possible assistance to the poor and the needy. Religious bodies also perform their respective duties in this connection in their own humble way. Homes for the aged, orphanages and other similar charitable institutions are needed in under-developed countries.

As the materially rich should have compassion on the materially poor and try to elevate them, it is the duty of the spiritually rich, too, to have compassion on the spiritually poor and sublimate them, though they may be materially rich. Wealth alone cannot give genuine happiness.

Peace of mind can be gained not by material treasures but by spiritual treasures. Many in this world are badly in need of substantial spiritual food, which is not easily obtained, as the spiritually poor far exceed the materially poor numerically, as they are found both amongst the rich and the poor.

There are causes for these two kinds of diseases. Compassionate men and women must try to remove the causes if they wish to produce an effective cure. Effective measures have been employed by various nations to prevent and cure diseases not only of mankind but also of animals.

The Buddha set a noble example by attending on the sick Himself and exhorting His disciples with the memorable words:

“He who ministers unto the sick ministers unto me.”

Some selfless doctors render free services towards the alleviation of suffering. Some expend their whole time and energy in ministering to the poor patients even at the risk of their lives. Hospitals and free dispensaries have become a blessing to humanity but more are needed so that the poor may benefit by them. In under-developed countries the poor suffer through lack of medical facilities. The sick have to be carried for miles with great inconvenience to the nearest hospital or dispensary for medical treatment. Sometimes, they die on the way. Pregnant mothers suffer most. Hospitals, dispensaries, maternity homes, etc., are essential needs in backward village areas. The lowly and the destitute deserve the compassion of wealthy men and women. Sometimes, servants and workers are not well paid, well fed or well clothed and, more often than not, they are ill-treated. Justice is not meted out to them. They are neglected and are powerless as there is nobody to plead for them. Glaring cases of inhuman cruelty receive publicity in some exceptional cases. Many such cases are not known. These unfortunate ones have no other alternative but to suffer meekly even as the Earth suffers in silence. The Buddha’s advocacy of compassion has tremendous validity in our own times.