Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of a Brahmin Recluse which is verse 388 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 388 is part of the Brāhmaṇa Vagga (The Brāhmaṇa) and the moral of the story is “Evil barred, a brahmin; by steady life, a monk; rid of stains, a hermit one truly is”.

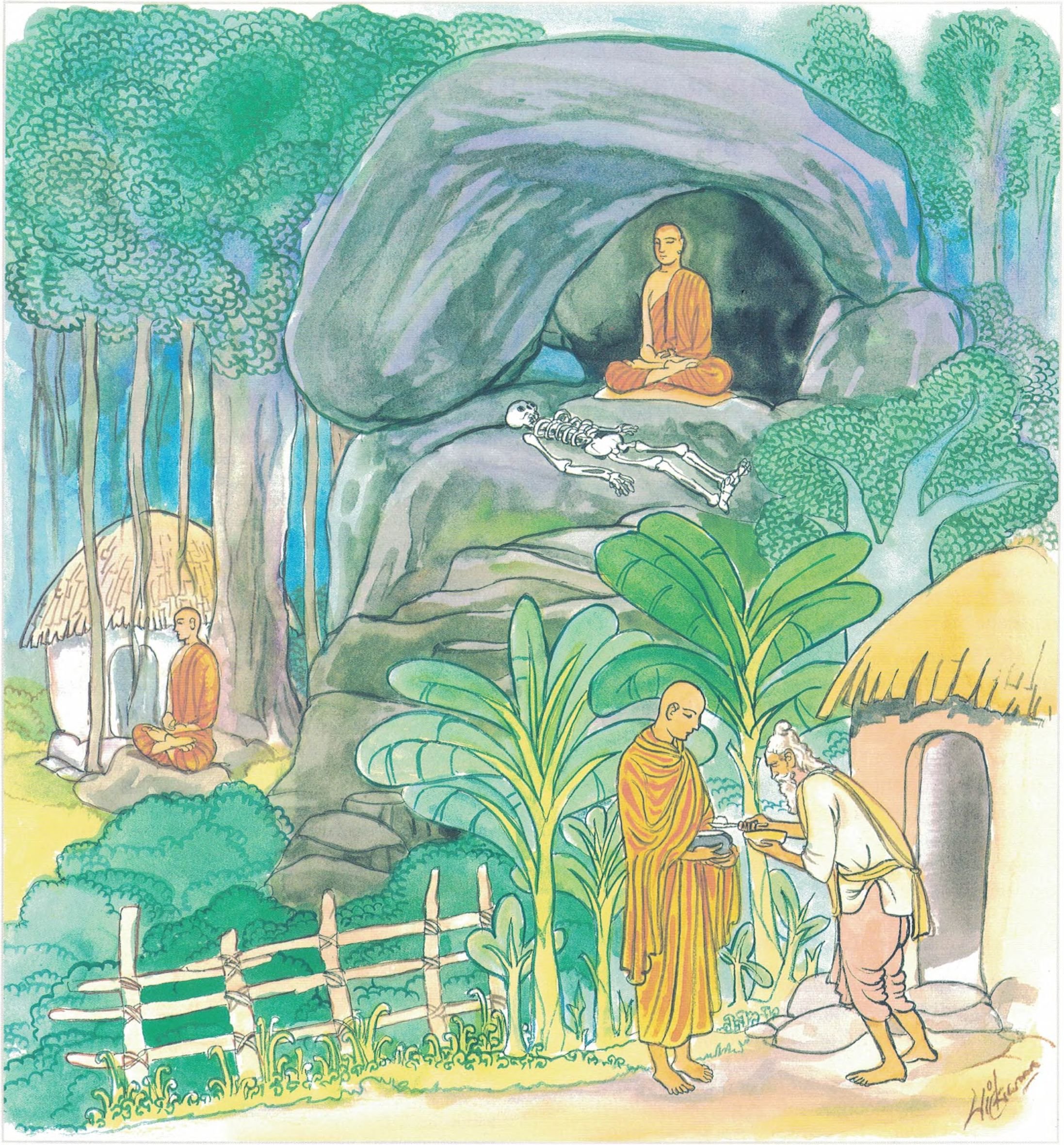

Verse 388 - The Story of a Brāhmin Recluse

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 388:

bāhitapāpo'ti brāhmaṇo samacariyā samaṇo'ti vuccati |

pabbājay'attano malaṃ tasmā pabbajito'ti vuccati || 388 ||

388. By barring-out badness a ‘brahmin’ one’s called and one is a monk by conduct serene, blemishes out of oneself therefore one’s known as ‘one who’s left home’.

Evil barred, a brahmin; by steady life, a monk; rid of stains, a hermit one truly is. |

The Story of a Brāhmin Recluse

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to a brāhmin ascetic.

The story is told of a certain brāhmin, that he retired from the world under a teacher other than the Buddha, and having so done, thought to himself, “The Buddha calls his own disciples monks; I, too, am a monk, and he ought to apply that title to me too.”

So he approached the Buddha and asked him about the matter. Said the Buddha, “It is not alone for the reason which you have given me that I call a man a monk. But it is because the evil passions and the impurities have gone forth from him that a man is called one who has gone forth, a monk.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 388)

bāhitapāpo iti brāhmaṇo vuccati samacariyā samaṇo iti

vuccati attano malaṃ pabbājayati tasmā pabbajito iti vuccati

bāhitapāpo iti: because he has got rid of evil; brāhmaṇo [brāhmaṇa]: brāhmaṇa; vuccati: is called; samacariyā: lives with serenity of senses; samaṇo iti vuccati: samaṇa he is called; attano malaṃ pabbājayati: he gets rid of his defilements; tasmā: because of that; pabbajito iti vuccati: he is called a; pabbajita

One has got rid of sinful action is called a brāhmaṇa. One of serene senses is called samaṇa. A person is called pabbajita because he has done away with all his faults.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 388)

brāhmaṇo, samaṇo pabbajito: a brāhmin, a monk, a wandering ascetic. These are all categories of priests in the religious landscape of the Buddha’s day. They pursued a multitude of paths to moksha. Here the Buddha explains who a real priest, monk or brahamin is. In His day, religious systems were many and varied. Of the contemporary religious sects, one of the most intriguing was the system created by Nighaṇṭhanāthaputta.

The life-story of Nighaṇṭhanāthaputta is very similar to that of the Buddha. Although these two great Teachers were contemporaries, wandering and preaching in the same region, nowhere is it recorded that they met each other. Nighaṇṭhanāthaputta preached in the Ardha Māgadhi language while the Buddha did so in Suddha Māgadhi (pure Māgadhi). In later times among the Jain there was a division into two sects: (1) Svetāmbara Jaina (the white-clad sect) and (2) Dīghāmbara Jaina (the nude sect).

Nighaṇṭhanāthaputta was not a believer in creation (anishvaravādi). Never referring to the theory of Ishṭhāpurthi (creator) as given in the Vādas, he was a firm believer in kamma and its consequences. Regarding this doctrine, there is recorded in the Sāmaññaphala Sutta, in the Buddhist canon, the Cetanā Saṃvara, and similarly in the Upāli Sutta there is mentioned the Tridaṇḍa. As mentioned in these records, Nighaṇṭhanāthaputta’s doctrine is one of extreme non-violence.

Tridaṇḍa is divided into three types:

- kāyadaṇḍa (austere control and disciplining of the body);

- vāgdaṇḍa (austere control and disciplining of speech); and

- manodaṇḍa (austere control and disciplining of thought).

According to this system the followers of Nighaṇṭhanāthaputta. have to be constantly following the path of self-mortification in the practice of their religion. As in Buddhism with its concept of cetanā (will or volition). Jainism believed in kamma and its consequences. The people, to a very great extent, accepted this teaching. The Buddha had to lay down the Sikkhāpada (Vinaya rules) because of the influence of Jainism.

More specifically, the Vinaya rules regarding the rainy season were laid down by the Buddha owing to Jainism. From this it is evident that during that period Jainism was highly esteemed socially. According to the Jaina teaching even plants had a soul. Those who wear even a thread show an attachment to worldly comforts. All animate and inanimate things possess a soul. Hence, owing to this belief Jains cover their mouth with a piece of cloth even when they go on a journey.

The soul, according to Jainism, is of three kinds:

- nityasiddhāṭmaya (this is similar to the paramāṭma of the Hindus);

- muktātmaya (this is similar to the Āsava of the Buddhists);

- baddhātmaya (this is similar to the kamma of the Buddhists).

This baddhātmaya is said to pervade the cells of an individual’s body as long as the soul is steeped in kamma. One cannot secure release from saṃsāra. It is only by self-mortification that one can rid oneself of kamma. This teaching is not at all in accord with Buddhism, which explains kamma in a very different way. According to the teachings of Jain there are one hundred and fifty eight different kinds of kamma.