Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Five Hundred Monks which is verse 277-279 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 277-279 is part of the Magga Vagga (The Path) and the moral of the story is “All conditioned things are transient. Disillusionment through this knowledge leads to release” (first part only).

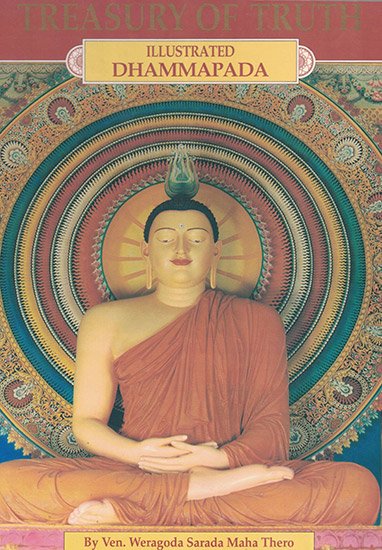

Verse 277-279 - The Story of Five Hundred Monks

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 277-279:

sabbe baṅkhārā aniccā'ti yadā paññāya passati |

atha nibbindati dukkhe esa maggo visuddhiyā || 277 ||

sabbe baṅkhārā dukkhā'ti yadā paññāya passati |

atha nibbindati dukkhe esa maggo visuddhiyā || 278 ||

sabbe dhammā anattā'ti yadā paññāya passati |

atha nibbindati dukkhe esa maggo visuddhiyā || 279 ||

277. When with wisdom one discerns transience of conditioned things one wearily from dukkha turns treading the path to purity.

278. When with wisdom one discerns the dukkha of conditioned things one wearily from dukkha turns treading the path to purity.

279. When with wisdom one discerns all knowables are not a self one wearily from dukkha turns treading the path to purity.

All conditioned things are transient. Disillusionment through this knowledge leads to release. |

All conditioned things are sorrow-fraught. This knowledge clears your path… |

All things are without self. This disillusionment leads to the path… |

The Story of Five Hundred Monks

While residing at Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to five hundred monks.

The story that these five hundred monks, who had received a meditation topic from the Buddha and who had striven and struggled with might and main in the forest without attaining arahatship, returned to the Buddha for the purpose of obtaining a meditation topic better suited to their needs.

The Buddha inquired within himself, “What will be the most profitable meditation topic for these monks?” Then he considered within himself, “In the dispensation of the Buddha Kassapa these monks devoted themselves for twenty thousand years to meditation on the characteristic of impermanence; therefore, the characteristic of impermanence shall be the subject of the single stanza which I shall give.”

And he said to them, “Monks, in the sphere of sensual existence and in the other spheres of existence all the aggregates of existence are by reason of unreality impermanent.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 277)

sabbe saṅkhārā aniccā iti yadā paññāya passati

atha dukkhe nibbindati esa visuddhiyā maggo

sabbe: all; saṅkhārā: component things; aniccā: are transient; iti yadā: when this; paññāya passati: (you) realize with insight; atha: then; dukkhe: from suffering; nibbindati: (you) get detached; esa: this is; visuddhiyā: to total freedom of blemishes (Nibbāna); maggo [magga]: the path

All component things, all things that have been put together, all created things are transient, impermanent, non-constant. When this is realized through insight, one achieves detachment from suffering. This is the path to total freedom from blemishes.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 278)

sabbe saṅkhārā dukkhā iti yadā paññāya passati

atha dukkhe nibbindati esa visuddhiyā maggo

sabbe: all; saṅkhārā: component things; dukkhā’ti: are suffering;iti yadā: when this; paññāya passati: (you) realize with insight; atha: then; dukkhe: from suffering; nibbindati: (you) get detached; esa: this is; visuddhiyā: to total freedom of blemishes (Nibbāna); maggo [magga]: the path

All component things–all things that have been put together–all created things are sorrow-fraught. When this is realized through Insight, one achieves detachment from suffering. This is the path to total freedom from suffering.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 279)

sabbe dhammā anattā iti yadā paññāya passati

atha dukkhe nibbindati esa visuddhiyā maggo

sabbe: all; dhammā: states of being; anattā: (are) without a self; iti yadā: when this; paññāya passati: (you) realize with insight; atha: then; dukkhe: from suffering; nibbindati: (you) get detached; esa: this is; visuddhiyā: to total freedom of blemishes (Nibbāna); maggo [magga]: the path

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 277-279)

All states of being are without a self. When this is realized through insight, one achieves detachment from suffering. This is the path to total freedom from suffering.

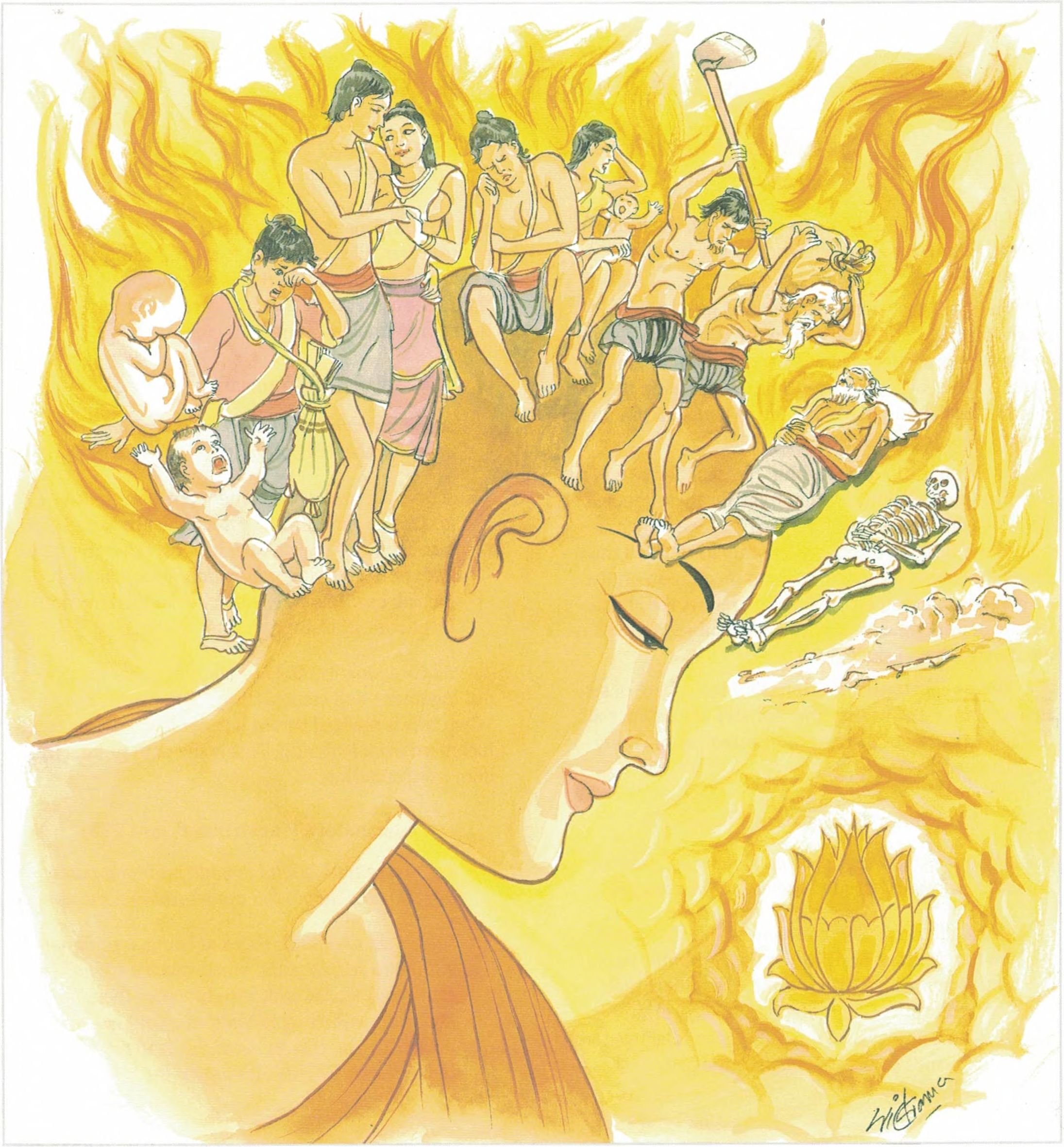

aniccā: impermanent. In the Buddhist system, there are three characteristics of existence–anicca, dukkha and anatta. Impermanence implies that all forms of existences end up in decay and death. With the exception of Nibbāna, this applies to all phenomena.

Whoever constantly keeps in mind the fact that he would someday be subjected to death and that death is inevitable, would be eager to fulfil his duties to his fellow men before death, and this would certainly make him heedful in respect of this world and the next. It has been said, therefore, that a “monk who is engaged in the thought of death is ever heedful (Maraṇasati-manuyutto bhikkhu satatam appamatto hoti).

There are, however, extremists who say that reflection on death is an unnecessary thought that tends to retard the progress of a person. This is not so. For, thus has Visnusarman said in the Pancatantra:

Samcintya tamugradandam

mrtyum manusyasya vicaksanasya

Varsambusikta iva carmabandhah

Sarvaprayatnah Sithili bhavanti.(All the endeavours of a wise man who constantly thinks of death that causes severe punishment, are bound to become easy and flexible like leather bags moistened with rain water.)

It must be noted, however, that Buddhism never advocated dejection and neglect of one’s duties by pondering over death. On the contrary, what is taught in Buddhism is the fulfillment of one’s duties and obligations in the best possible manner even on the eve of death.

The Buddha had expressed His categorical disapproval of the postponement of one’s duties: thus says the Buddha:

Ajjeva kiccam ātappaṃ Ko jañña Māraṇaṃ suve...

(Today itself, one should strive for the accomplishment of one’s tasks; for, who knows whether death would strike tomorrow…)

The Uraga Jātaka recounts how a father, when his only son lay dead, bitten by a serpent, sent news of the incident to the inmates of the house and without awaiting their arrival, continued to plough his field; he was a person who regularly practiced meditation on death. By thus reflecting on the inevitability of death, one becomes increasingly active in the performance of one’s duties; one also develops a sense of fearlessness towards death. Furthermore, such a person takes care not to commit the slightest sin that is likely to cause suffering in the next world; he also becomes a free person who has forsaken all bonds and attachments to his beloved ones and other objects.

Both monks and laymen, unmindful of death and considering themselves as immortals, are often heedless in cultivating virtues. They engage themselves in strife and arguments and are often dejected, with their hopes and aspirations shattered. At times, they postpone their work with the hope of doing it on a grand scale in the future, and end up without being able to do anything. Therefore, it is only proper that one should daily reflect on death. Out of the four-fold topics of meditation prescribed for Buddhists as suitable to be practiced everywhere (sabbattha kammaṭṭhāna), reflection on death comes as the fourth (Buddhānussati mettā ca– asubhaṃ Maraṇassati).

“Ekadhammo bhikkave bhāvito bahulīkato ekanta nibbidāya virāgāya nirodhāya upasamāya abhiññāya sambodhāya nibbāṇāya saṃvattati; katamo ekadhammo maraṇassati.” There is, O’ monks, one Dhamma which when meditated on and practiced constantly, leads to detachment from the world of becoming, freedom from all defilements, emancipation from worldly sorrows, acquisition of higher knowledge, realization of the four noble truths, and attainment of Nibbāna. What is this one Dhamma? It is the constant reflection on death. The loftiness and significance of reflection on death is clearly conveyed by this doctrinal passage.

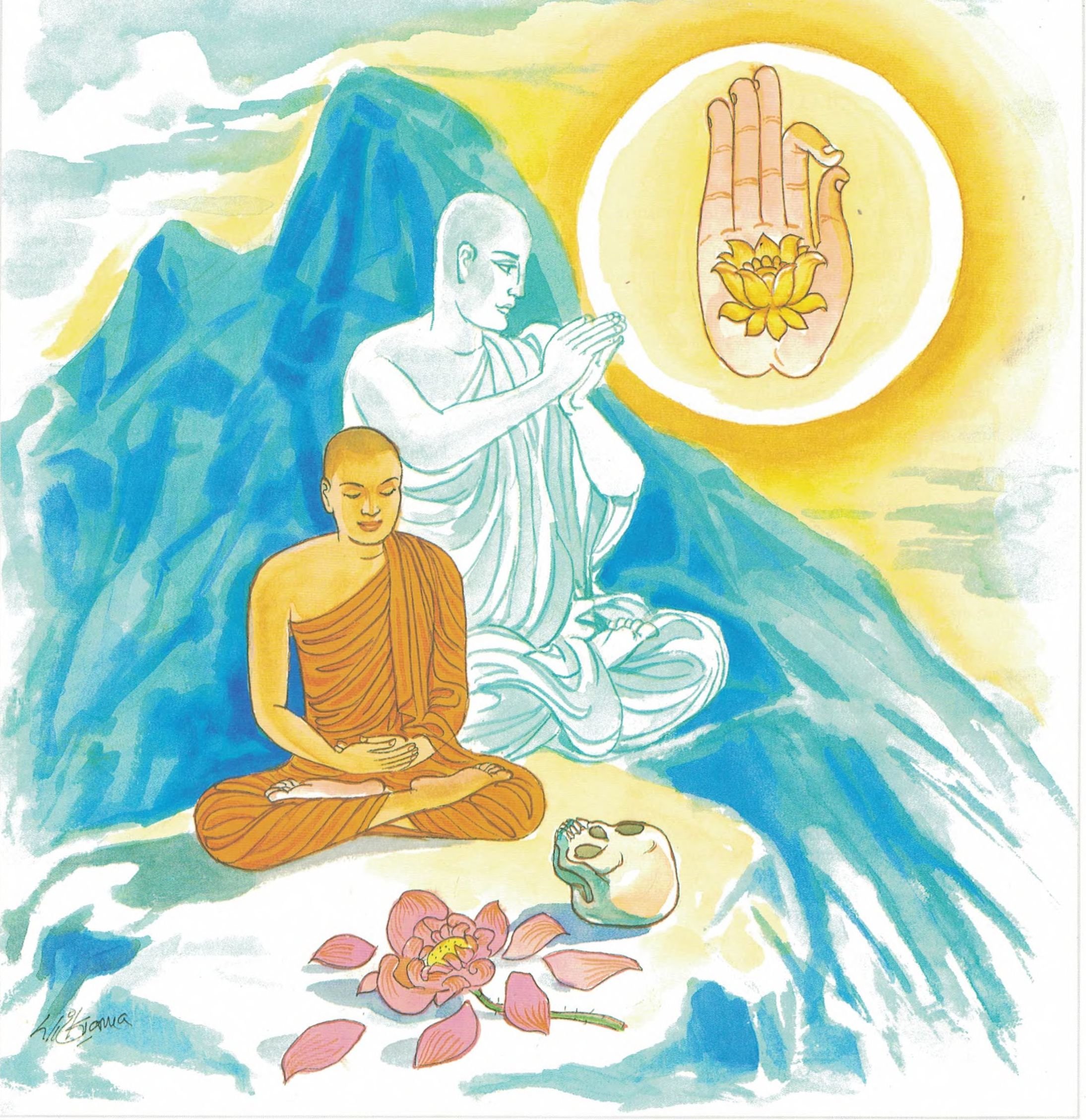

dukkha: suffering. This is the second of the three characteristics of existence. The four noble truths, too, pivot around suffering (dukkha).

The Buddha’s Teaching regarding the four noble truths deals with the knowledge of suffering, the cause of suffering, the cessation, and the way to the cessation of suffering. The truth regarding suffering tells us that all beings are subject to birth, decay, disease and death. In brief, the five aggregates (skandhās): physical phenomena (rūpa); feelings of sensation (vedanā);perception (saññā); volitional activities (samkhāra);consciousness (viññāna); all constitute suffering. This is the truth regarding suffering, and the right understanding of it is sammādiṭṭhi. This Sammādiṭṭhi is basically essential for the understanding of the real nature of the world. Of the four noble truths, the understanding of suffering is of cardinal importance. Thus this is considered first.

The second noble truth deals with the cause of suffering, and this is craving or attachment (taṇhā). It is because of this craving that all beings continue to be born and reborn in saṃsāra. What a being enjoys as happiness is really suffering, which springs from this craving or attachment. Man pursues many pleasures, seeking happiness like the deer deluded by a mirage because of this craving or attachment. To be emancipated from Saṃsāra or the cycle of birth and rebirth one must understand the truth regarding craving.

This craving assumes three forms:

- Kāma taṇhā (attachment to sensual pleasures);

- Bhava taṇhā (attachment to existence);

- Vibhava taṇhā (attachment to non-existence).

Kāma taṇhā arises out of sakkāyadiṭṭhi or the idea that there exists an unchanging entity or a permanent soul–that there is such an entity as ‘I’. A person who is under such a delusion always strives to pander to his five senses. It is because of kāma taṇhā that happiness is regarded as enjoyment through the five senses. This is a delusion. As kāma taṇhā increases, suffering arises. Thus kāma taṇhā is a cause of suffering.

Bhava taṇhā is the craving that arises in a being for termination of life. This craving arises in a being who believes in the existence of a soul (sassatadiṭṭhi).

Vibhava taṇhā is the craving that arises in a being for the enjoyment of sensual pleasures as an end in itself. This craving arises because of the non-belief in an after-life (ucchedadiṭṭhi). The Lokāyata theory of Cārvāka and Ajita Kesakambala belongs to this category. In the Brahmajāla Sutta of the Buddhist canon seven types of ucchedavāda are expounded.

The person who develops right understanding, the first constituent of the noble eight-fold path, realizes that this craving is the cause of suffering. The second of the four noble truths deals with the cause of this craving or suffering. Right understanding gives the knowledge of how to end suffering. The Third noble Truth deals with the cessation of suffering. This cessation of suffering is brought about by eradicating the three kinds of craving (taṇhakkhaya) which give rise to suffering. This is Nibbāna.

Right understanding gives us the knowledge of the path to the cessation of suffering. The fourth noble truth deals with the cessation of suffering (dukkhanirodhagāmini patipadāgnāna). The path to the cessation of suffering is the noble eight-fold path. This is the middle path. It is, therefore, impossible to eradicate the three forms of craving which give rise to suffering without following the middle path.

Anatta: no-soul concept. This is the third of the three characteristics of existence as the Buddha expounded. The idea of a lack of a soul, or a permanent and abiding self, or an ātman that is eternal is extremely difficult for most individuals to understand.

The sum total of the doctrine of change taught in Buddhism is that all component things that have conditioned existence are a process and not a group of abiding entities, but the changes occur in such rapid succession that people regard mind and body as static entities. They do not see their arising and their breaking up, but regard them unitarily, see them as a lump (ghāna saññā) or whole.

Those ascetics and brāhmins who conceive a self in diverse ways conceive it as either the five aggregates of clinging, or as any one of them.

“Herein the untaught worldling… considers body as the Self, Self as possessed of body as included in the self, self as included in the body… similarly as to feeling, perception, volitional formations, and consciousness… Thus this is the wrong view. The I am notion is not abandoned…

It is very hard, indeed, for people who are accustomed continually to think of their own mind and body and the external world with mental projections as wholes, as inseparable units, to get rid of the false appearance of ‘wholeness’. So long as man fails to see things as processes, as movements, he will never understand the anatta (no-Soul) doctrine of the Buddha. That is why people impertinently and impatiently put the question: “If there is no persisting entity, no unchanging principle, like self or soul (ātman), what is it that experiences the results of deeds here and hereafter?”

Another view of the three characteristics of existence are the characteristics of impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha) and not-self (anatta). These three characteristics are always present in or are connected with existence, and they reflect the real nature of existence. They help us to deal with existence. What we learn to develop as a result of understanding the three characteristics is renunciation. Once we understand that existence is universally characterised by impermanence, suffering and not-self, we eliminate our attachment to existence. Once we eliminate our attachment to existence, we gain the threshold of Nibbāna. This is the purpose served by the understanding of the three characteristics. It removes attachment by removing delusions, the misunderstanding that existence is permanent, is pleasant and has something to do with the self. This is why understanding the three characteristics is central to wisdom.