Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Venerable Tissa which is verse 240 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 240 is part of the Mala Vagga (Impurities) and the moral of the story is “Rust born of iron eats it up. So do evil deeds the man who transgresses”.

Verse 240 - The Story of Venerable Tissa

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 240:

ayasā'va malaṃ samuṭṭhitaṃ taduṭṭhāya tam'eva khādati |

evaṃ atidhonacārinaṃ sakakammāni nayanti duggatiṃ || 240 ||

240. As rust arisen out of iron itself that iron eats away, done beyond what’s wise lead to a state of woe.

Rust born of iron eats it up. So do evil deeds the man who transgresses. |

The Story of Venerable Tissa

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery the Buddha spoke this verse with reference to Venerable Tissa.

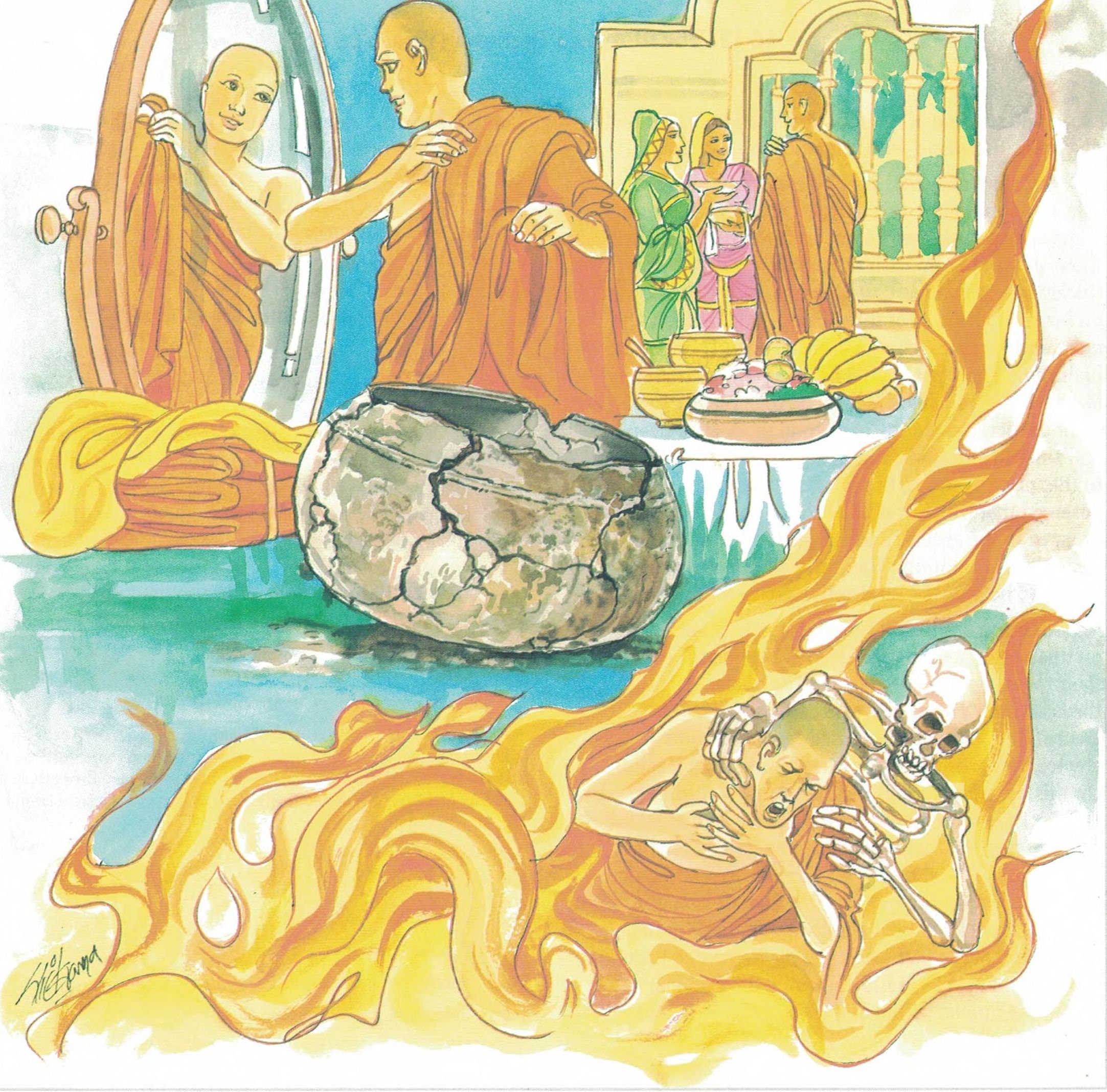

The story goes that a certain youth of respectable family, who lived at Sāvatthi, retired from the world, became a monk, and made his full profession, becoming known as Venerable Tissa. Subsequently, while he was in residence at a monastery in the country, he received a coarse cloth eight cubits in length. Having completed residence, he celebrated the Terminal Festival, and taking his cloth with him, went home and placed it in the hands of his sister. Thought his sister, “This robe-cloth is not suited to my brother.” So with a sharp knife she cut it into strips, pounded them in a mortar, whipped and beat and cleaned the shoddy, and, spinning fine yarn, had it woven into a robe-cloth. The Venerable procured thread and needles, and assembling some young monks and novices who were skilled makers of robes, went to his sister and said, “Give me that cloth; I will have a robe made out of it.” She took down a robecloth nine cubits in length and placed it in the hands of her youngest brother. He took it, spread it out, and said, “My robecloth was a coarse one, eight cubits long, but this is a fine one, nine cubits long. this is not mine; it is yours. I don’t want it. Give me the same one I gave you.” “Venerable, this cloth is yours; take it.” He refused to do so.

Then his sister told him everything she had done and gave him the cloth again, saying, “Venerable, this one is yours; take it.” Finally, he took it, went to the monastery and set the robemakers to work. His sister prepared rice-gruel, boiled rice, and other provisions for the robe-makers, and on the day when the cloak was finished, gave them an extra allowance. Tissa looked at the robe and took a liking to it. Said he, “Tomorrow I will wear this robe as an upper garment.” So he folded it and laid it on the bamboo rack.

During the night, unable to digest the food he had eaten, he died, and was reborn as a louse in that very robe. When the monks had performed the funeral rites over his body, they said, “Since there was no one to attend him in his sickness, this robe belongs to the congregation of monks; let us divide it among us.” Thereupon that louse screamed, “These monks are plundering my property!” And thus screaming, he ran this way and that. The Buddha, even as he sat in the Perfumed Chamber, heard that sound by Supernatural Audition, and said to Venerable Ānanda, “Ānanda, tell them to lay aside Tissa’s robe for seven days.” The Venerable caused this to be done. At the end of seven days that louse died and was reborn in the Abode of the Tusita gods. On the eighth day the Buddha issued the following order, “Let the monks now divide Tissa’s robe and take their several portions.” The monks did so and, amongst themselves, discussed as to why the Buddha had caused Tissa’s robes to be put aside for seven days.

When the Buddha was told of their discussion, he said, “Monks, Tissa was reborn as a louse in his own robe. When you set about to divide the robe among you, he screamed, ‘They are plundering my property.’ Had you take his robe, he would have cherished a grudge against you, and because of this sin would have been reborn in Hell. That is the reason why I directed that the robe should be laid aside. But now he has been reborn in the Abode of the Tusita gods, and for this reason, I have permitted you to take the robe and divide it among you.” The Buddha continued, “Craving is, indeed, a grievous matter among living beings here in the world. Even as rust which springs from iron eats away the iron and corrodes it and renders it useless, so also this thing which is called craving, when it arises among living beings here in the world, causes these same living beings to be reborn in Hell and plunges them to ruin.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 240)

ayasā eva samuṭṭhitaṃ malaṃ taduṭṭhāya tameva khādati,

evaṃ atidhonacārinaṃ sakakammāni duggatiṃ nayanti

ayasā eva: out of the iron itself; samuṭṭhitaṃ malaṃ [mala]: rust that has arisen; taduṭṭhāya: originating there itself; tameva: that itself; khādati: eats (erodes); evaṃ: thus; atidhonacārinaṃ [atidhonacārina]: monks who transgress the limits; sakakammāni: one’s own (evil) actions; duggatiṃ [duggati]: to bad state; nayanti: lead (the evil doer)

The rust springing from iron consumes the iron itself. In the same way, bad actions springing out of an individual destroy the individual himself.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 240)

duggati: bad state; woeful state; woeful course of existence. The word derives from du + gati.

gati: course of existence, destiny, destination. There are five courses of existence: hell, animal kingdom, ghost-realm, human world, heavenly world. Of these, the first three count as woeful courses (duggati, apāya), the latter two as happy courses (sugati).