Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Three Ascetics which is verse 209-211 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 209-211 is part of the Piya Vagga (Affection) and the moral of the story is “With no application and misapplication, the pleasure-seeker envies the zealous one” (first part only).

Verse 209-211 - The Story of Three Ascetics

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 209-211:

ayoge yuñjam attānaṃ yogasmiñ ca ayojayaṃ |

atthaṃ hitvā piyaggāhī pihet'attānuyoginaṃ || 209 ||

mā piyehi samāgañchī appiyehi kudācanaṃ |

piyānaṃ adassanaṃ dukkhaṃ appiyānañ ca dassanaṃ || 210 ||

tasmā piyaṃ na kayirātha piyāpāyo hi pāpako |

ganthā tesaṃ na vijjanti yesaṃ natthi piyāppiyaṃ || 211 ||

209. One makes an effort where none’s due with nothing done where effort’s due, one grasps the dear, gives up the Quest envying those who exert themselves.

210. Don’t consort with dear ones at any time, nor those not dear, ’tis dukkha not to see the dear, ’tis dukkha seeing those not dear.

211. Others then do not make dear for hard’s the parting from them. For whom there is no dear, undear in them no bonds are found.

With no application and misapplication, the pleasure-seeker envies the zealous one. |

Not seeing dear ones is painful, so is seeing the disliked. Make no contact with both. |

Reject thoughts of likes and dislikes. Freed of bonds, suffer ye no pain of separation. |

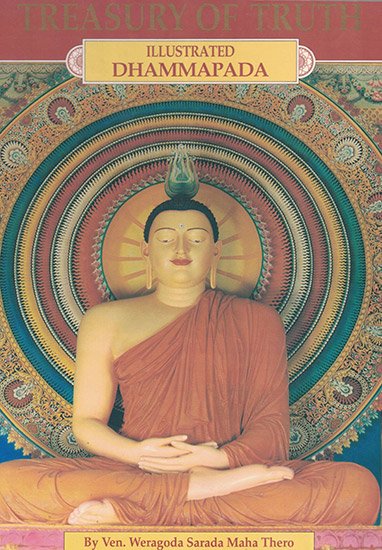

The Story of Three Ascetics

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to a trio, consisting of a father, a mother, and a son.

The story goes that in a certain household at Sāvatthi there was an only son who was the darling and delight of his mother and father. One day some monks were invited to take a meal at the house, and when they had finished they recited the words of thanksgiving. As the youth listened to the words of the Dhamma he was seized with a desire to become a monk, and straightaway asked leave of his mother and father. They refused to permit him to do so. Thereupon the following thought occurred to him, ‘When my mother and father are not looking, I will leave the house and become a monk.”

Now whenever the father left the house, he committed the son to the care of his mother, saying, “Pray keep him safe and sound;” and whenever the mother left the house, she committed the son to the care of the father. One day, after the father had left the house, the mother said to herself, “I will indeed keep my son safe and sound.” So she braced one foot against one of the door-posts and the other foot against the other doorpost, and sitting thus on the ground, began to spin her thread. The youth thought to himself, “I will outwit her and escape.” So he said to his mother, “Dear mother, just remove your foot a little; I wish to attend to nature’s needs.” She drew back her foot and he went out. He went to the monastery as fast as he could, and, approaching the monks, said, “Receive me into the Sangha, Venerables.” The monks complied with his request and admitted him to the Sangha.

When his father returned to the house, he asked the mother, “Where is my son?” “Husband, he was here but a moment ago.” “Where can my son be?” thought the father, looking about. Seeing him nowhere, he came to the conclusion, “He must have gone to the monastery.” So the father went to the monastery and, seeing his son garbed in the robes of a monk, wept and lamented and said, “Dear son, why do you destroy me?” But after a moment he thought to himself, “Now that my son has become a monk, why should I live the life of a layman any longer?” So of his own accord, he also asked the monks to receive him into the Sangha, and then and there retired from the world and became a monk.

The mother of the youth thought to herself, “Why are my son and my husband tarrying so long?” Looking all about, she suddenly thought, “Undoubtedly they have gone to the monastery and become monks.” So she went to the monastery and, seeing both her son and her husband wearing the robes of monks, thought to herself, “Since both my son and my husband have become monks, what further use have I for the house-life?” And, of her own accord, she went to the community of nuns and retired from the world.

But even after mother and father and son had retired from the world and adopted the religious life, they were unable to remain apart; whether in the monastery or in the convent of the nuns, they would sit down by themselves and spend the day chatting together. The monks told the Buddha what was going on. The Buddha sent for them and asked them, “Is the report true that you are doing this and that?” They replied in the affirmative. Then said the Buddha, “Why do you do so? This is not the proper way for monks and nuns to conduct themselves.” “But it is impossible for us to live apart.” “From the time of retirement from the world, such conduct is highly improper; it is painful both to be deprived of the sight of those who are dear, and to be obliged to look upon that which is not dear;for this reason, whether persons or material things be involved, one should take no account either of what is dear or of what is not dear.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 209)

attānaṃ ayoge yuñjaṃ yogasmiṃ ayojayaṃ ca

atthaṃ hitvā piyaggāhi attānuyoginaṃ piheti

attānaṃ [attāna]: (where) one; ayoge: should not get engaged; yuñjaṃ [yuñja]: who gets engaged; yogasmiṃ [yogasmi]: where one should get engaged; ayojayaṃ [ayojaya]: who does not engage; ca atthaṃ [attha]: what should be done; hitvā: neglecting; piyaggāhi: grasps only what appeals; attānuyoginaṃ [attānuyogina]: those who seek selfish ends; piheti: desire

Being devoted to what is wrong, not being devoted to what is right, abandoning one’s welfare, one goes after pleasures of the senses. Having done so, one envies those who develop themselves.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 210)

piyehi appiyehi kudācanaṃ mā samāgañchi piyānaṃ

adassanaṃ appiyānaṃ dassanaṃ ca dukkhaṃ

piyehi: the endearing ones; appiyehi: those who are disliked; kudācanaṃ [kudācana]: never; mā samāgañchi: never associate closely; piyānaṃ [piyāna]: of the loved ones; adassanaṃ [adassana]: not seeing; appiyānaṃ dassanaṃ ca: (and) also seeing disliked persons; dukkhaṃ [dukkha]: (are both) painful

Never associate with those whom you like, as well as with those whom you dislike. It is painful to part company from those whom you like. It is equally painful to be with those you dislike.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 211)

tasmā piyaṃ na kayirātha, hi piyāpāyo pāpako

yesaṃ piyāppiyaṃ natthi tesaṃ ganthā na vijjanti

tasmā: therefore; piyaṃ na kayirātha: do not take a liking; hi: because; piyāpāyo [piyāpāya]: separating from those we like; pāpako [pāpaka]: is evil; yesaṃ [yesa]: for someone; piyāppiyaṃ [piyāppiya]: pleasant or unpleasant; natthi: there is not; tesaṃ [tesa]: to them; ganthā: knots of defilements; na vijjanti: are not seen

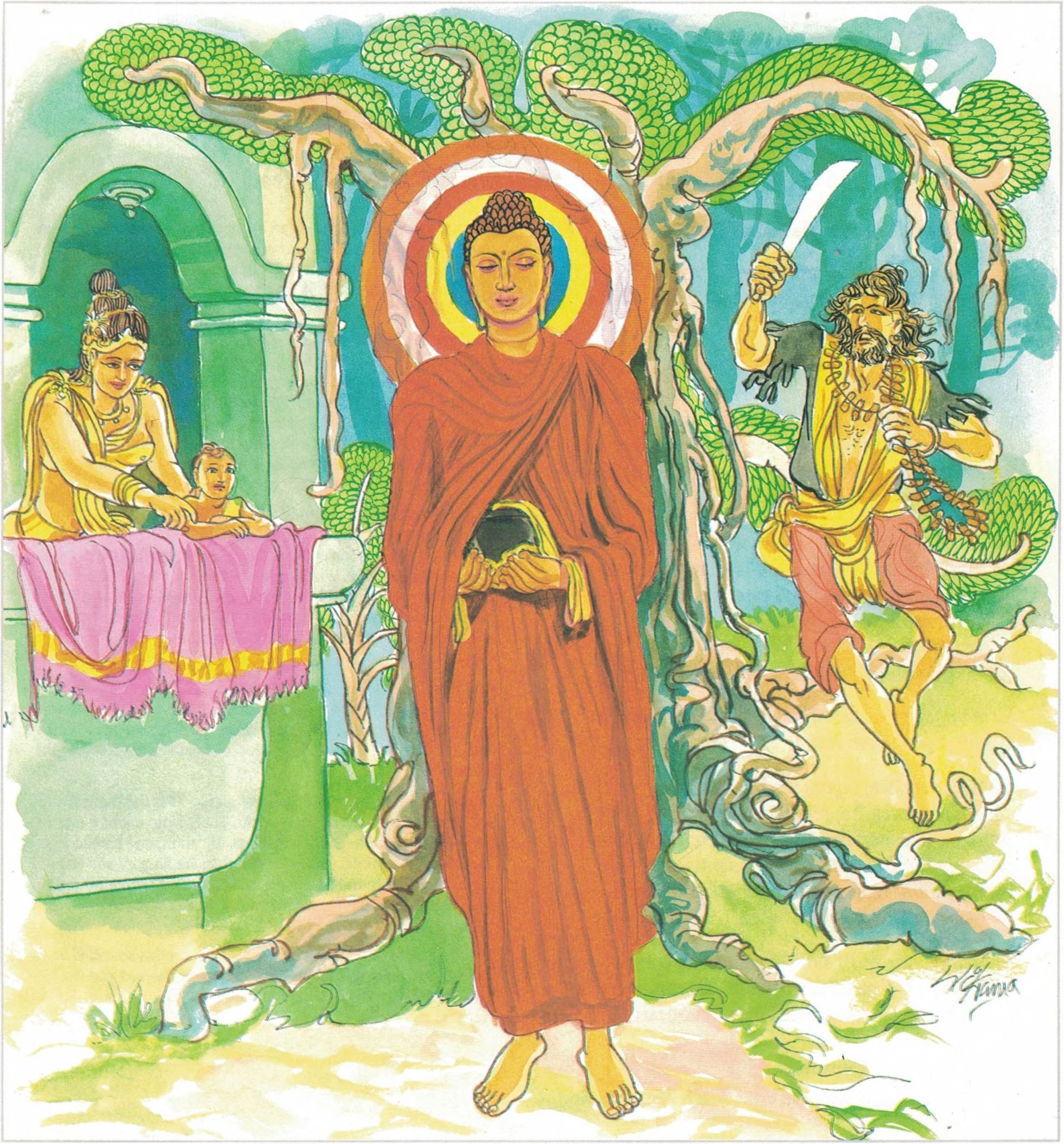

Therefore, one must not have endearments; because, separation is painful. For those who are free of bonds there are no endearments or non-endearments.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 209-211)

dukkha: suffering. Dukkha is the first of the Four Noble Truths. As a feeling dukkha means that which is difficult to be endured (du–difficult; kha–to endure). As an abstract truth dukkha is used in the sense of contemptible (du) and emptiness (kha). The world rests on suffering–hence, it is contemptible. The world is devoid of any reality–hence, it is empty or void. Dukkha means contemptible void.

Average men are only surface-seers. An ariya sees things as they truly are. To an ariya all life is suffering and he finds no real happiness in this world which deceived mankind with illusory pleasures. Material happiness is merely the gratification of some desire. No sooner is the desired thing gained than it begins to be scorned. Insatiate are all desires. All are subject to birth (jāti), and consequently to decay (jarā), disease (vyādhi), and finally to death (marana). No one is exempt from these four inevitable causes of suffering.

Impeded wish is also suffering. We do not wish to be associated with things or persons we detest, nor do we wish to be separated from things or persons we love, Our cherished desires are not, however, always gratified. What we least expect or what we least desire is often thrust on us. At times such unexpected unpleasant circumstances become so intolerable and painful that weak ignorant folk are compelled to commit suicide as if such an act would solve the problem.

Real happiness is found within, and is not to be defined in terms of wealth, power, honours or conquests. If such worldly possessions are forcibly or unjustly obtained, or are misdirected, or even viewed with attachment, they will be a source of pain and sorrow for the possessors.

Ordinarily, the enjoyment of sensual pleasures is the highest and only happiness to an average person. There is no doubt a momentary happiness in the anticipation, gratification, and recollection of such fleeting material pleasures, but they are illusory and temporary. According to the Buddha non-attachment (virāgatā) or the transcending of material pleasures is a greater bliss. In brief, this composite body itself is a cause of suffering.

This first truth of suffering, which depends on this so-called being and various aspects of life, is to be carefully analyzed and examined. This examination leads to a proper understanding of oneself as one really is.

Buddha has declared: Birth is dukkha. Birth means the whole process of life from conception to parturition. It is conception which is particularly meant here. Just to be caught up in a situation where one is tied down by bonds of craving to a solid, deteriorating, physical body–this is dukkha. By being lured into birth by craving or forced into it by kamma, one must experience dukkha. Then the whole operation of birth is so painful that if it goes wrong in some way, as modern psychology has discovered, a deep mental scar, a kind of trauma, maybe left upon the infant’s mind. Lord Buddha, however, has declared from his own memories of infinite births, that to be born is a terrifying experience, so much so that most people prefer to forget it. There is another sense in which birth is really dukkha, for, in Buddha’s Teachings, birth-and-death are different phases of existence from moment to moment. Just as in the body new cells are being produced to replace old ones which are worn out, so in the mind, new objects are being presented, examined and dying down. This constant flow goes on day and night, on and on, so that if it is examined carefully, (with insight), it will be seen to be an experiential disease giving no peace, ensuring no security, and resulting in no lasting satisfaction. In a moment of experience events arise, subsist and pass away but this is a meaning of birthand-death only to be really understood with the aid of deep meditation and insight.

Old age is dukkha. This is perhaps more obvious. Teeth fall out, one’s nice glossy hair becomes thin and white, the stomach refuses to digest one’s favourite food, joints ache and creak and muscles grow weak; more serious than these physical afflictions are such manifestations as failing sight or difficulty in hearing–pages might be covered with them all. Most terrible of all is the mind’s declining ability to understand or to react intelligently, the increasing grip of habits and prejudices, the disinclination to look ahead (where death lies in wait) but to gaze back at the fondly remembered and increasingly falsified past. Lastly, one might mention that softness of the mind which is politely called ‘second childhood’, and accurately called ‘senility’. Not all beings, not all people will be subject to all of these conditions, but growing old surely entails experiencing some of them, experience which can only be distasteful.

Sickness is dukkha. Again, not all will be affected by diseases during life though it is certainly common enough. Consider this body: how intricate it is, how wonderful that it works smoothly even for five minutes, let alone for eight years. One little gland or a few little cells going wrong somewhere, marching out of step, and how much misery can be caused! Most people, again, prefer not to think about this and so suffer the more when they are forced to face it. To be convinced of the commonness of illness, one has only to look into hospitals, talk to doctors and nurses, or open a medical textbook. The diseases about which one can learn are enormous in number and fade off into all sorts of nasty conditions for which science has not yet been able to discover the causes. Mental diseases, brought on by a super-strong root of delusion variously mixed with greed and aversion, are also included here.

In the First Sermon of the Buddha, the central concept is the notion of suffering. Said the Buddha:

“The noble truth of suffering is this: Birth itself is suffering; old age is suffering; sickness is suffering; death is suffering, association with the unpleasant is suffering; separation from the beloved ones is suffering; non-acquisition of the desired objects is suffering. In brief, all the five aggregates of envelopment are suffering.”

“The noble truth of the cause of suffering is this: It is this craving which causes rebirth, which is attended with enjoyment. It takes delight here and there, namely, in sensual desires, in existence and in destruction.”

“The noble truth of the cessation of suffering is this: It is the complete avoidance, cessation, giving up, abandonment, release and detachment of that craving.”

“The noble truth of the way to the cessation of this suffering is the noble Eight-fold Path consisting of proper vision and proper thought.”

“This noble truth of suffering is a theory not heard of by me earlier, and in which arose my perception, insight, wisdom, knowledge and illumination. This noble truth of suffering, O monks, must be fully understood.”

“This noble truth of the cause of suffering is a theory not heard of by me earlier, and in which arose my perception, insight, wisdom, knowledge and illumination. This cause of suffering, O monks, must in fact be given up; and it has been give up by me.”

“This noble truth of the cessation of suffering is a theory not heard of by me earlier, and in which arose my perception, insight, wisdom, knowledge and illumination. This noble truth, O monks, must indeed, be developed; and it has been developed by me.”