Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Koka the Huntsman which is verse 125 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 125 is part of the Pāpa Vagga (Evil) and the moral of the story is “Whatever evil act is done against a virtuous person its evil will boomerang on the doer”.

Verse 125 - The Story of Koka the Huntsman

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 125:

yo appaduṭṭhassa narassa dussati |

suddhassa posassa anaṅgaṇassa |

tameva bālaṃ pacceti pāpaṃ |

sukhumo rajo paṭivātaṃ'va khitto || 125 ||

125. Who offends the inoffensive, the innocent and blameless one, upon that fool does evil fall as fine dust flung against the wind.

Whatever evil act is done against a virtuous person its evil will boomerang on the doer. |

The Story of Koka the Huntsman

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Koka the huntsman.

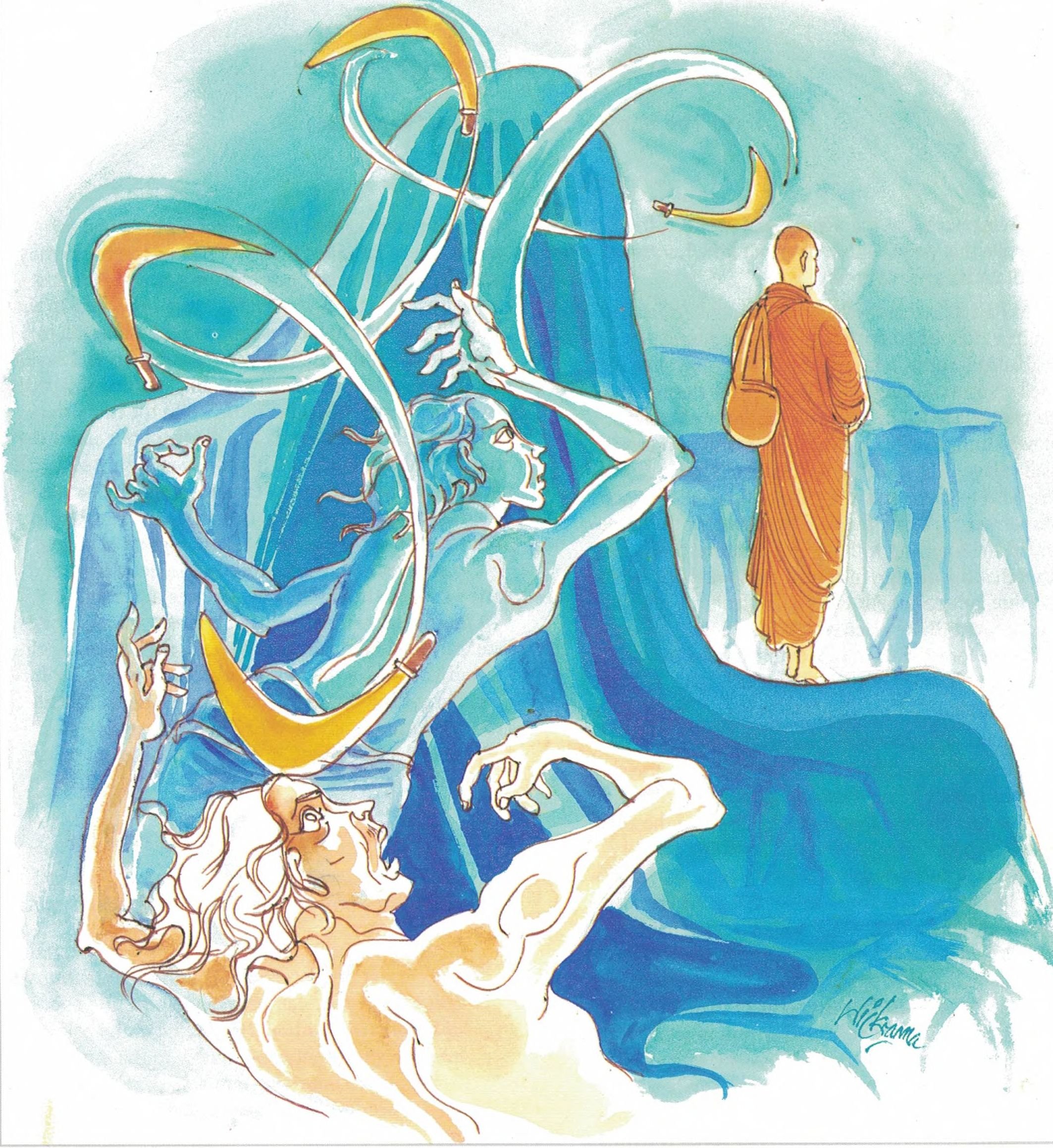

One morning, as Koka was going out to hunt with his pack of hounds, he met a monk entering the city for alms-food. He took that as a bad omen and grumbled to himself, “Since I have seen this wretched one, I don’t think I would get anything today,” and he went on his way. As expected by him, he did not get anything. On his way home also, he saw the same monk returning to the monastery, and the hunter became very angry. So he set his hounds on the monk. Swiftly, the monk climbed up a tree to a level just out of reach of the hounds. Then the hunter went to the foot of the tree and pricked the heels of the monk with the tip of his arrow. The monk was in great pain and was not able to hold his robes on; so the robes slipped off his body on to the hunter who was at the foot of the tree.

The dogs seeing the yellow robe thought that the monk had fallen off the tree and pounced on the body, biting and pulling at it furiously. The monk, from his shelter in the tree, broke a dry branch and threw it at the dogs. Then the dogs discovered that they had been attacking their own master instead of the monk, and ran away into the forest. The monk came down from the tree and found that the hunter had died and felt sorry for him. He also wondered whether he could be held responsible for the death, since the hunter had died for having been covered up by his yellow robes.

So, he went to the Buddha to clear up his doubts. The Buddha said, “My son, rest assured and have no doubt; you are not responsible for the death of the hunter;your morality (sīla) is also not soiled on account of that death. Indeed, that huntsman did a great wrong to one to whom he should do no wrong, and so had come to this grievous end.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 125)

yo appaduṭṭhassa suddhassa anaṅgaṇassa narassa

posassa dussati (taṃ) pāpaṃ paṭivātaṃ khitto

sukhumo rajo iva taṃ bālaṃ eva pacceti

yo: if someone; appaduṭṭhassa: is unblemished; suddhassa: is pure; anaṅgaṇassa: is free of defilements; narassa posassa: to such a human being; dussati: a person were to become harsh; pāpaṃ [pāpa]: that evil act; pāṭivātaṃ [pāṭivāta]: against the wind; khitto [khitta]: thrown; sukhumo rajo iva: like some fine dust; taṃ bālaṃ eva: to that ignorant person himself; pacceti: returns

If an ignorant person were to become harsh and crude towards a person who is without blemishes, pure, and is untouched by corruption, that sinful act will return to the evil-doer. It is very much like the fine dust thrown against the wind. The dust will return to the thrower.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 125)

anaṅgaṇassa: to one bereft of defilements–aṅganas. Aṅganas are defilements that are born out of rāga (passion), dosa (ill-will), and moha (ignorance). These are described as aṅganas (literally, open spaces;play-grounds) because evil can play about in these without inhibition. At times, ‘stains’, too, are referred to as aṅgana. Etymologically, aṅgana also means the capacity to deprave a person defiled by blemishes. In some contexts, aṅgana implies dirt. An individual who is bereft of defilements is referred to as anaṅgana.