The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part XII

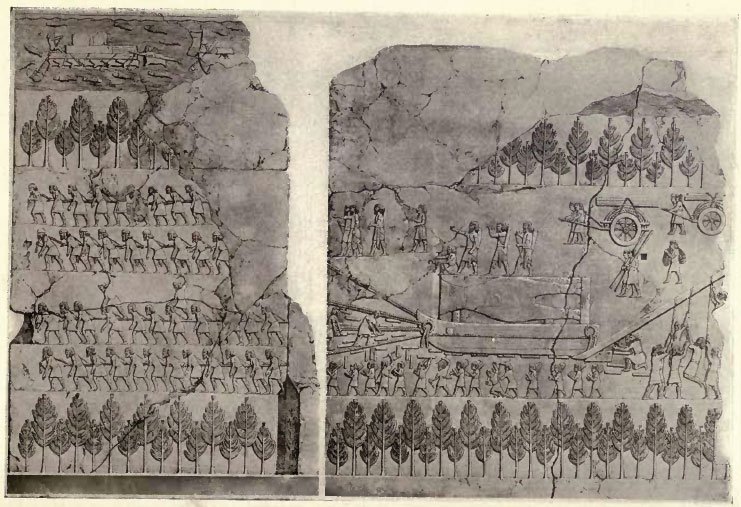

Of the same general character are the wall sculptures from the palace of Sennacherib, unearthed at Kouyunjik by Layard. [1] The later Assyrian artists were guided entirely by earlier models both in the selection of their subjects and in the execution. As we pass, however, from one reign to another we can note a certain advance in artistic execution and more particularly in the grouping of the figures.

A good illustration of this advance is to be seen in the series of alabaster bas-reliefs, showing King Sennacherib sitting on his throne outside the city of Lachish in Palestine, and receiving the prisoners of war and tribute from the captive cities of the surrounding states. The wooded surroundings are indicated by trees which, although conventionalized in form, are executed with considerable attention to details. What one notices particularly is the manner in which the high officials of the captured towns, with a royal personage at the head, are represented, followed by common prisoners in various attitudes.

Behind the prisoners are groups of captured women and children, some of them in wagons drawn by oxen, while interspersed throughout the long processions are the soldiers carrying the spoils of war. One receives the impression of a long triumphant procession passing by the royal throne, but without the usual exaggeration to which Assyrian artists were given and which spoils the effect in the case of many sculptures by overcrowding. Here everything is drawn on a proper scale.

PLATE LVIII

Fig. 1, King Sennacherib of Assyria (705-681 B.C.) at Lachish (Palestine)

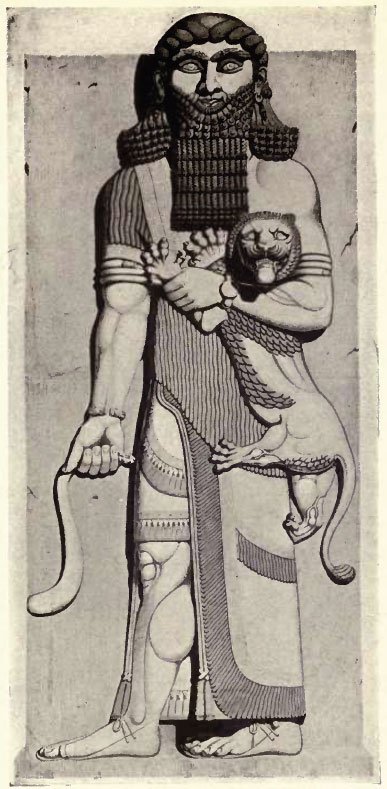

PLATE LVII

PLATE LVII

Fig. 1, Gilgamesh, The Hero of the Babylonian Epic

There are just enough details to enable us to interpret the scene correctly, which thus answers the conditions suitable for the genuine illustration of an historical text. Less satisfactory is the endeavor to portray the actual attack on the city of Lachish, which evidently stood on an eminence. This portrayal involved problems of perspective which were beyond the range of the Assyrian artist, but despite this defect the grouping of the figures is again skilfully carried out.

We receive the impression of a very large and successful army in the aim of the arrows of the soldiers, as well as in the damage done by the machines of war, hurling heavy catapults against the walls of the besieged town (see Plate LVIII).

Very effective, again, are a series of designs showing the loading and the transporting of one of the huge colossal human-headed bulls intended for the palace of the king. The mechanical devices for moving this heavy object are shown in so clear a manner as to make any further commentary useless. The bull is placed on a huge sled supported by rollers, which are moved as required so as to reduce the power necessary to pull the sled. The men carrying the extra poles and the extra ropes are shown, as well as the officers standing on the colossal figure and giving the necessary directions.

Of particular interest is the representation of the manner in which the lever at one end is pulled down through the united strength of a large number of men, who attach themselves by means of ropes to the enormous crowbar (see Plate LIX).

Through these illustrations one also obtains an idea of the large number of workmen at the disposal of the rulers for the purpose of erecting their great buildings and for their building operations. Human life appears to have been an exceedingly cheap commodity in Assyrian days. There was never any lack of men to equip the enormous armies and, similarly, the king was never in lack of the many thousands required for the constant task of building temples and palaces and other huge edifices.

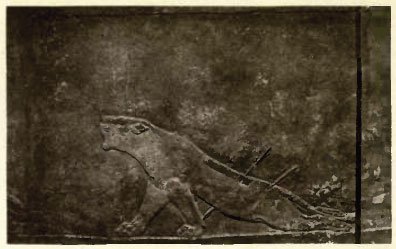

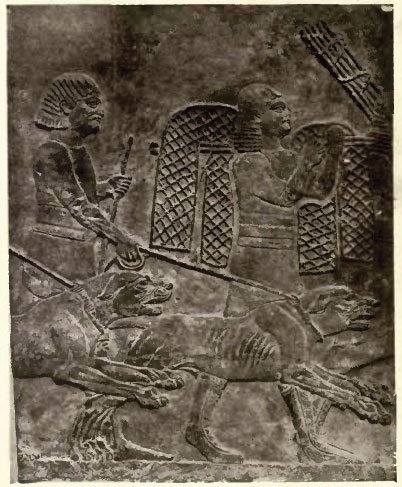

By far the most elaborate and on the whole the most artistic sculptural decorations of the royal palaces of Assyria date from the days of the grand monarque, Ashurbanapal (668-626 B.C.), in whose reign the artistic development of Assyria as well as her military glory reached its height. It is necessary to see for one's self at the British Museum, or in the series of photographs made from the originals, the extended group of the scenes of warfare and of the hunt sculptured on basreliefs that lined thewalls of the large rooms of the palace of the king at Nineveh, in order to realize the general plan followed by the artists in thus illustrating the campaigns of the king and their royal master's sport (Plate LX).

Such is the attention given to details that by means of these bas-reliefs we can follow, even without the accompanying descriptive texts and the elaborate annals that we possess of the king's reign, the course of his mad chase for power and glory % The criticism to be passed on many of the limestone or alabaster slabs is that the artist attempts, particularly in the battle scenes, to put too much in a limited space.

The scenes are frequently too crowded for artistic effect. The horses in these scenes are particularly well executed ; they dash along with fiery spirit and add to the impression of the fierceness of the fight (see Plate LXI).

The scenes here chosen are taken from the series illustrative of the campaign of Ashurbanapal against Teumman, King of Susa, Assyria's most powerful rival. We see the Assyrian monarch in his chariot in the midst of the fray, hotly intent upon capturing Teumman himself, who in one of the scenes is depicted as defended by his son. We see as the climax of the struggle the Elamite king decapitated, a part of the Susian army thrown into the river and the rest taken prisoners.

PLATE LIX

Fig. 1, Transporting colossal figure of a winged bull

PLATE LX

Fig. 1, Dying Lioness

Fig. 2, Attendants carrying nets for the chase and leading dogs

In a continuation of the campaign we observe the procession of prisoners and the head of Teumman carried off as a trophy of war in a chariot; and as the fitting close to the campaign, Ashurbanapal and his queen are seated in a garden, enjoying life, while as a ghastly, silent witness to the domestic scene the head of Teumman hangs in the arbor overarching the divans on which the king and queen are lying in an easy posture (Plate LXII).

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See above, p. 19, and for further illustrations Paterson, Assyrian Sculptures, The Palace of Sinachenb (The Hague, 1912).