The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part I

In any general survey of the history of Babylonia and Assyria there are two facts of fundamental importance to be borne in mind : first, that the course of civilization in the land of the Euphrates and Tigris proceeds to the norfh, and second, that the culture is the outcome of a mixture of two diverse elements of a non-Semitic with a Semitic population.

The obvious conclusion from the first fact is that the settlements in the south, in what is known as the Euphrates Valley, are older than those in the north a conclusion confirmed by the excavations conducted at southern mounds, which have yielded us the documents for tracing the civilization to a very early period, though as yet insufficient for carrying us back to the small beginnings. The second fact prepares us for the distinguishing feature of the oldest period as likewise revealed by the monuments, to wit, the struggle between the non-Semites or the Sumerians, and the Semites or Akkadians for supremacy.

This struggle represents the natural process in the assimilation of two apparently incompatible elements. Civilization may be described as the spark that ensues when opposing ethnic elements come into contact. Culture up to a certain grade may develop in any centre spontaneously, but a high order of civilization is always produced through the combination of heterogeneous ethnic elements.

There is no more foolish boast than that of purity of race. A pure race, as I have it put elsewhere, [1] if it exists at all, is also a sterile race.

Whether the Semitic Akkadians were the first settlers in the Euphrates Valley or the non-Semitic Sumerians is a question to which, as indicated in the last chapter, [2] no definite reply can be given in the present state of our knowledge. My own inclination is to side with Eduard Meyer, [3] to give the benefit of the doubt to the Akkadians and to assume that the Sumerians, who we have every reason to believe were a mountainous people, entered the Valley from the northeast (or northwest) as conquerors bringing a certain degree of culture with them, but which through the contact with the Akkadian population was further stimulated and modified until it acquired the traits distinguishing it when we obtain our earliest glimpse of political, social and religious conditions in the Euphrates Valley.

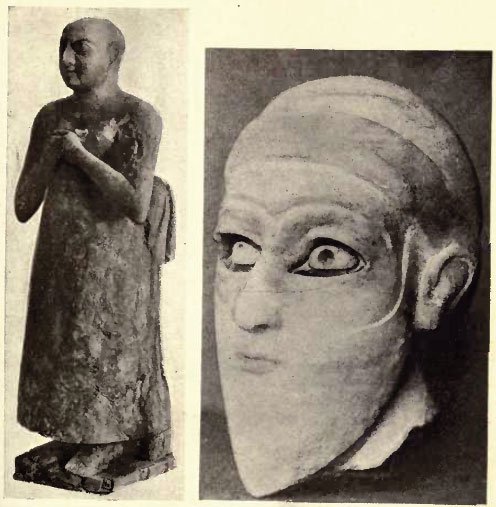

PLATE XXII

Fig. 1 (left), Sumerian Type (Telloh)

Fig. 2 (right), Semitic Type (Bismya)

Fortunately, through the monuments of Telloh, Sippar, Nippur and Bismya, and through the designs on numerous seal cylinders, we are in a position to picture to ourselves this non-Semitic race. [4] They are portrayed in contrast to the Akkadians as beardless and generally, though not always, with shaven heads. The general type suggests a comparison with the Mongolian race. The shape of the head was inclined towards roundness, the cheek bones were prominent and the nose was not full and fleshy as was the case with the Akkadians.

The dress in the earliest period consisted of a plain or fringed garment, hanging from the waist or was formed in more elaborate fashion of three to five flounces yielding, however, at a later period to a shawl or mantle, decorated with a border, drawn over the left shoulder and falling in straight folds.

In contrast, we find the Akkadians represented with hair and beard, though it would appear that in consequence of a new wave of Semitic immigration about the time of Hammurapi or shortly before, the Bedouin custom was introduced of shaving the moustache.

The features, particularly the long-shaped head and the fleshy nose, are unmistakably Semitic. In dress the Semites are represented by the loin cloth or by a plaid wrapped around the body, falling in parallel bands, with the ends thrown around the left shoulder.

The Sumerians appear also to have had the custom of wearing wigs, as the Egyptians, perhaps limited to ceremonial occasions, though to what extent and during what periods the custom prevailed it is difficult to say.Curiously enough the gods, even in the oldest monuments, have abundant hair and long beards, [5] but with lips and cheeks often shaven, from which Professor Meyer has drawn the inference that the Sumerians, while retaining some of the customs that they brought with them, assimilated their gods to those worshipped in the land into which they came and therefore represented them as Semitic.

Beside some form of writing which, as pointed out, the Sumerians may have brought with them, but further developed after their conquest of the Euphrates Valley, they appear to have been skilled in sculpturing in terracotta and in stone, advancing gradually also to working in metals. Naturally, here again it is difficult to draw the line between what they brought into the country and the share of their artistic achievements due to their contact with the Semitic settlers, but since the Euphrates Valley is devoid of stone and metals, the balance is again in favor of the assumption that they brought some measure of artistic skill with them. [6]

The architecture in the earliest period is conditioned by the native soil which furnishes clay as a building material that was readily adapted for the construction of houses and temples, consisting of both unburnt and burnt bricks. The only characteristic structure that may be safely ascribed to Sumerian initiative is the stage-tower attached to the temples in all important centres. [7]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria, p. 5.

[2]:

Page 107.

[3]:

Sumerier und Semiten in Babylonien, p. 107, seq.

[4]:

See the accompanying illustrations, and further in Meyer, Sumerier und Semiten in Babylonien, and in Jastrow, Bildermappe eur Religion Babyloniens und Assyriens, Nos, 1-7.

[5]:

See Meyer, I.e., p. 95, seq.

[6]:

Further details in Chapter VII.

[7]:

See above II, note 13 ; pp. 23 and 30, seq.