Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria

by Morris Jastrow | 1911 | 121,372 words

More than ten years after publishing his book on Babylonian and Assyrian religion, Morris Jastrow was invited to give a series of lectures. These lectures on the religious beliefs and practices in Babylonia and Assyria included: - Culture and Religion - The Pantheon - Divination - Astrology - The Temples and the Cults - Ethics and Life After Death...

Lecture VI - Ethics And Life After Death

THE view that life continues in some form after death has ensued is so common among people on the level of primitive culture, or who have just risen above this level, that its presence in advanced religions may be regarded as a legacy bequeathed from the earliest period in the history of mankind. To the savage and the untutored all nature is instinct with life. The changes and activity that he sees about him, in the woods and fields, in the streams and mountains and in the heavens—the boundless extent of ceaseless change—he ascribes to an element which he instinctively associates with the life of which he is conscious in himself, and he interprets this life in terms applicable to himself. Man in the earlier stages of his development is unable to conceive of life once begun as coming to an end, just as an unsophisticated child who, when it begins to ponder on the mystery of existence, is incapable of grasping the thought of death as a total extinction of life. The doubt comes at a later stage of mental development and so, in the history of mankind, the problem involved in a discussion regarding life after death is to determine the factors that led man to question the continuance of life in some form after it had fled from the body.

In the Old Testament it is only in the later books, like Ecclesiastes and Job, that the question is raised or suggested whether or not there is anything for man to look forward to after the breath of life has passed out of him. We may detect in certain aspects of the problem in these frankly skeptical productions of the Hebrew mind the influence—direct or indirect—of Greek philosophical thought, which early began to concern itself with this problem. Out of this doubt there arises after an interval of some centuries, on the one hand, the Jewish and Christian doctrine of the immortality of the soul, and on the other, the belief in a resurrection of the dead in some form. In Buddhism we see the persistency of the belief that life is continuous leading to the hope of release from life, as the ideal that can be attained only by those who, after a succession of existences in which they have schooled themselves to get rid of the desire of living, have merited also by their increasing purity the rare reward of Nirvâna.[1]

Here and there we find in Babylonian-Assyrian literature faint suggestions of skepticism, but the prevailing view throughout all periods is that the dead continue in a conscious or semi-conscious state after this life is come to an end. To be sure, the condition of the dead is not one to be envied. They are condemned to inactivity, which in itself might not be regarded as an unmixed evil, but this inactivity carries with it a deprivation of all pleasures. Deep down in the bowels of the earth there was pictured a subterranean cave in which the dead are huddled together. The place is dark, gloomy, and damp, and in a poetic work it is described as a neglected and forlorn palace, where dust has been allowed to gather—a place of dense darkness where, to quote the fine paradox of Job (x., 22), “even light is as darkness.” It is a land from which there is no return, a prison in which the dead are confined for all time, or if the shade of some spirit[2] does rise up to earth, it is for a short interval only, and merely to trouble the living. The horror that the dwelling-place of the dead inspired is illustrated by the belief that makes it also the general abode of the demons, though we have seen that they are not limited to this abode.

Again, this dwelling-place is pictured as a great city, and, curiously enough, it is at times designated like the temple of Enlil at Nippur as E-Kur-Bad, “Mountain-house [or “temple”] of the dead.” The most common name for this abode, however, is Aralū —a term that occurs in Sumerian compositions, but may nevertheless be a good Semitic word. By the side of this term, we find other poetic names, as “the house of Tammuz,” based upon the fact that the solar god of spring and vegetation is obliged to spend half of the year in the abode of the dead, or Irkallu, which is also the designation of a god of the subterranean regions, or Cuthah—the seat of the cult of Nergal,—because of the association of Nergal, the god of pestilence and death, with the lower world. The names and metaphors all emphasise the gloomy conceptions connected with the abode of the dead.

It was, however, inevitable that speculation by choicer minds should dwell on a theme so fascinating and important, and endeavour to bring the popular conceptions into harmony with the conclusions reached in the course of time in the temple-schools. Corresponding to the endeavour to connect with the personified powers of nature certain ethical qualities, reflecting a higher degree of moral development, we meet at least the faint inkling of the view that the gods, actuated by justice and mercy, could not condemn all alike to a fate so sad as eternal confinement in a dark cave. Besides Aralu, there was also an “Island of the Blest,” situated at the confluence of the streams, to which those were carried who had won the favour of the gods. One of these favourites is Ut-Napishtim, who was sought out by Ea, the god of humanity, as one worthy to escape from a deluge that destroyed the rest of mankind; and with Ut-Napishtim, his wife was also carried to the island, where both of them continued to lead a life not unlike that of the immortal gods. But though the theory of this possible rescue seems to have arisen at a comparatively early period, it does not appear, for some reason, to have been developed to any extent. In this respect, Babylonia presents a parallel to Greece, where we likewise find the two views, Hades for the general mass of humanity and a blessed island for the rare exceptions—the very rare exceptions—limited to those who, like Menelaos, are closely related to the gods, or, like Tiresias, favoured because of the possession of the divine gift of prophecy in an unusual degree.

We might have supposed that, among the Babylonians, the rulers, as standing much closer to the gods than the common people, would have been singled out for the privilege of a transfer to the Island of the Blest, but this does not appear to have been the case. Like the kings and heroes of the Greek epic, they all pass to the land of no-return, to the dark dwelling underground. An exception is not even made for kings like Sargon and Naram-Sin of Akkad, or for Dungi of the Ur dynasty and his successors, and some of the rulers of Isin and Larsa, who have the sign for deity attached to their names, and some of whom had temples dedicated in their honour, just like gods. The divinity of these Babylonian kings appears to have been, as with the Seleucid rulers, a political and not a religious prerogative, and the evidence would seem to show[3] that this political deification of kings was closely bound up with their control of Nippur as the paramount religious centre of the country. In theory, the ruler of this city was the god, Enlil, himself, and, therefore, he who had control of the city was put on a parity with the god, as his son or representative—the vicar of Enlil on earth, a kind of pontifex maximus, with the prerogatives of divinity as the symbol of his office.

We do not find that the speculations of the Babylonian and Assyrian priests ever led to any radical modification of the conceptions concerning Aralñ. It remains a gloomy place,—a tragic terminus to earthly joys, and always contemplated with horror. The refrain, running through all the lessons which the priests attached to popular myths in giving them a literary form, is that no man can hope to escape the common fate. Enkidu,[4] who is introduced into the Gilgamesh epic[5] and appears to be in some respects a counterpart to the Biblical Adam,[6] is created by Aruru, the fashioner of mankind, but when slain by the wiles of the goddess Ishtar, goes to Aralfi. as the rest of mankind. Even Gilgamesh himself, the hero of the epic, half-man, half-god, whose adventures represent a strange conglomeration of dimmed historical tradition and nature myths, is depicted as being seized with the fear that he too, like Enkidu, may be dragged to the world of the dead. He seeks to fathom the mystery of death and, in the hope of escaping Aralft, undertakes a long journey in quest of Ut-Napishtim, to learn from him how he had attained immortality. The latter tells Gilgamesh the story of his escape from the destructive deluge. Ut-Napishtim and his wife are filled with pity for the stranger, who has been smitten with a painful disease. They afford him relief by mystic rites, based on the incantation ritual, but they cannot cure him. Gilgamesh is told of a plant which has the power of restoring old age to youth. He seeks for it, but fails to find it, and, resigned to his fate, he returns to his home, Uruk.

The last episode in the epic furnishes a further illustration of the sad thoughts aroused in the minds of the priests and people at the contemplation of the fate in store for those who have shuffled off the mortal coil. Gilgamesh is anxious to find out at least how his friend and companion, Enkidu, fares in Aralû. In response to his appeal, the shade of Enkidu rises before him.

“Tell me, my friend,” Gilgamesh implores,

“tell me the law of the earth which thou hast experienced.”

Mournfully the reply comes back,

“I cannot tell thee, my friend, I cannot tell thee.”

Enkidu continues:

Were I to tell thee the law of the earth which I have experienced, Thou would 'st sit down and weep the whole day.

There is only one thing that can make the fate of the dead less abhorrent. A proper burial with an affectionate care of the corpse ensures at least a quiet repose.

Such a one rests on a couch and drinks pure water,

But he whose shade has no rest in the earth, as I have seen and you will see,[7]

His shade has no rest in the earth.

Whose shade no one cares for, as I have seen and you will see,

What is left over in the pot, remains of food

That are thrown in the street, he eats.

II

Proper burial is, therefore, all essential, even though it can do no more than secure peace for the dead in their cheerless abode, and protection for the living by preventing the dead from returning in gaunt forms to plague them. Libations are poured forth to them at the grave, and food offered by sorrowing relatives.

The greatest misfortune that can happen to the dead is to be exposed to the light of day; far down into the Assyrian period we find this exemplified in the boast of Ashurbanapal that he had destroyed the tombs of the kings of Elam, and removed their bodies from their resting-place.[8] The corpses of the Babylonians who took part in a rebellion, fomented by his treacherous brother Shamash-shumukin, Ashurbanapal scattered, so he tells us,[9] “like thorns and thistles” over the battle-field, and gave them to dogs, and swine, and to the birds of heaven. At the close of the inscriptions on monuments recording the achievements of the rulers, and also on the so-called boundary stones,[10] recording grants of lands, or other privileges, curses are hurled against any one who destroys the record; and as a part of these curses is almost invariably the wish that the body of that ruthless destroyer may be cast forth unburied.

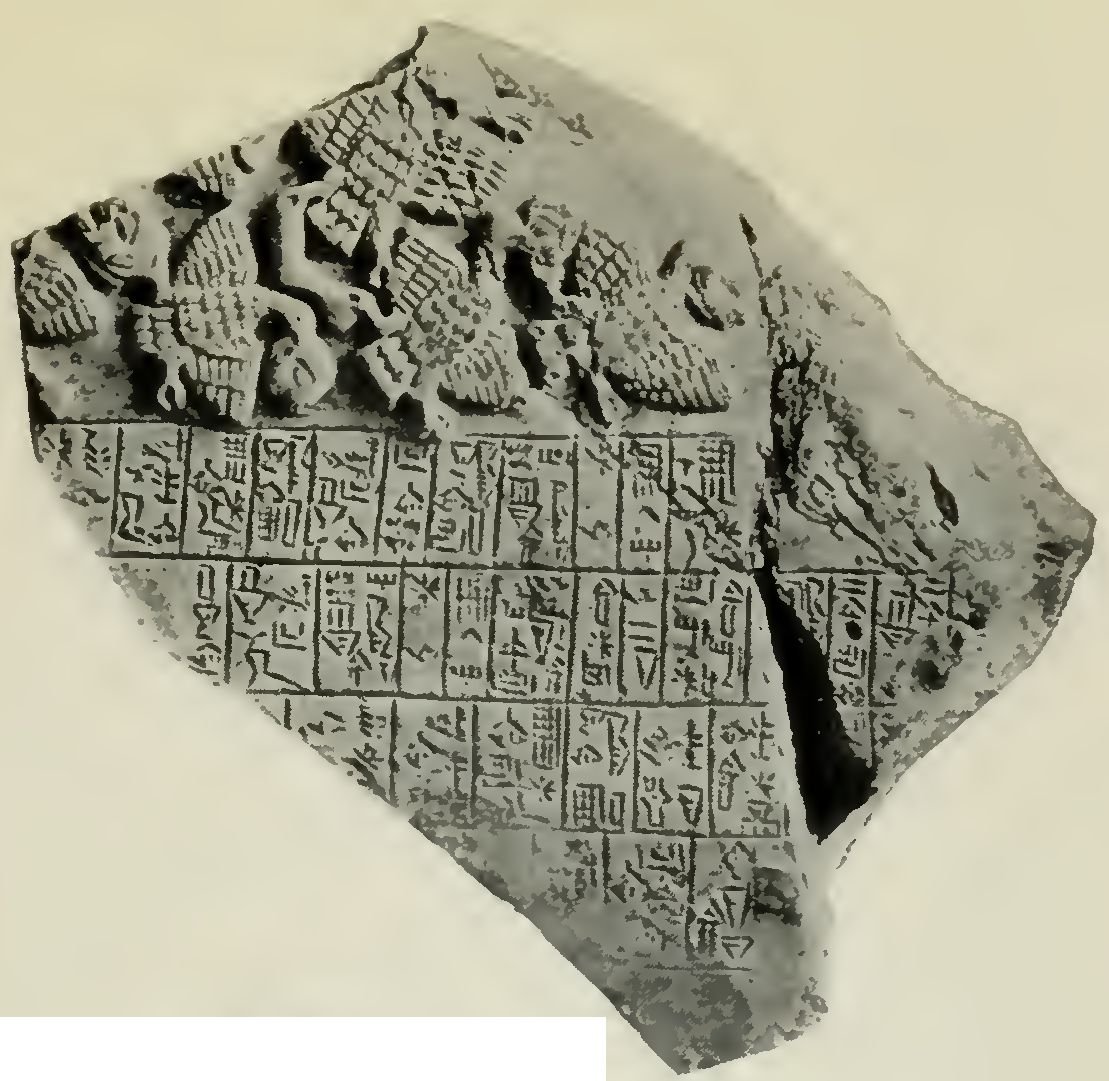

Mutilation of the corpses of foes, so frequently emphasised by Assyrian rulers,[11] is merely another phase of this curse upon the dead. On one of our oldest pictorial monuments, portraying and describing the victory of Eannatum, the patesi of Lagash (ca . 3000 B.C.), over the people of Umma, the contrast between the careful burial of the king’s warriors, and the fate allotted to the enemy is shown by vultures flying off with heads in their beaks.[12]

The monument is of further interest in depicting the ancient custom of burying the dead unclad, which recalls the words of Job (i., 21),

“naked came I out of my mother’s womb and naked shall I return thither,”

which may be an adumbration of this custom. To this day, among Mohammedans and orthodox Jews, the body is not buried in ordinary clothes but is merely wrapped in a shroud; this custom is only a degree removed from the older custom of naked burial. Whether or not in Babylonia and Assyria this custom was also thus modified as a concession to growing refinement, we do not know, but presumably in later times the dead were covered before being consigned to the earth. There are also some reasons for believing that, at one time, it was customary to sew the dead in bags, or wrap them in mats of reeds. At all times, however, the modes of burial retained their simplicity. If from knowledge derived from later ages we may draw conclusions for earlier ages, it would seem that the general custom was to place the dead in a sitting or half-reclining posture, on reed mats, and to cover them with a large jar or dish, or to place them in clay compartments having the shape of bath-tubs.[13] The usual place of burial seems to have been in vaults, often beneath the houses of the living.[14] In later periods, we find the tubs replaced by the long slippershaped clay coffins, with an opening at one end into which the body was forced.[15] Throughout these various customs a desire is indicated not merely to bury the body, but to imprison it safely so as to avoid the danger of a possible escape. Weapons and ornaments were placed on the graves, and also various kinds of food, though whether or not this was a common practice at all periods has not yet been determined.

In general, it may be said, the tombs of the Babylonians and Assyrians were always exceedingly simple, and we find no indications whatever that even for monarchs elaborate structures were erected as their resting-place. Herein Babylonia and Assyria present a striking contrast to Egypt, which corresponds to the difference no less striking between the two nations in their conceptions of life after death. In Egypt, the preservation of the body was a condition essential to the well-being of the dead, whereas in Babylonia a mere burial was all-sufficient and no special care was taken to keep the body from decay. The elaborate mortuary ceremonial in Egypt[16] finds no parallel in the Euphrates Valley, where the general feeling appears to be that for the dead there was not much that could be done. Such customs as were observed were prompted, as has been said, rather by a desire to protect the living from being annoyed or tortured by the shades of the unburied or neglected dead. That this fear was genuine is indicated by the belief in a class of demons, known as etimmu,[17] which means the “shade” of a departed person. This conception is best explained as a survival of primitive beliefs found elsewhere, which among many people in a stage of primitive culture led to a widespread and complicated ancestor worship. That this worship existed in Babylonia also is highly probable, but it must have died out as part of the official cult before we reach the period for which we have documentary material; we find no references to it in the ritual texts

III

In seeking a reason why the speculations of the temple-schools, regarding the mysteries of the universe, should not have led to the doctrine of a more cheerful destiny for the dead such as in the Blessed Island (to which, as we have seen, only a few favourites of the gods were admitted), we are surprised by the almost complete absence of all ethical considerations in connection with the dead.

While much stress was at all times laid upon conduct agreeable to the gods (and one of the most sig-ficant members of the pantheon is Shamash, the god of justice and righteousness), the thought that good deeds will find a reward from the gods after life has ceased is absent from the religious literature of Babylonia and Assyria. There is a special pantheon for the nether world, where the dead sojourn, but there is no figure such as Osiris in the Egyptian religion, the judge of the dead, who weighs the good deeds against the bad in order to decide the destiny of the soul. To be sure, everything is done by the living to secure the favour of the gods, to appease their anger, and to regain their favour by elaborate expiatory rites, and by confession of sins, and yet all the hopes of the people are centred upon earthly happiness and present success. The gods appear to be concerned neither for the dead nor with them. Their interest, like that of their worshippers, was restricted to the living world.

Even with so exceptional a mortal as Ut-Napishtim, who is carried to the Blessed Island, no motive is ascribed to Ea, who warns Ut-Napishtim of the coming destruction of mankind, and provides for his escape by bidding him build a ship. It is not even alleged of Ut-Napishtim that he was a faithful worshipper, much less that by exemplary conduct he merited the special favour bestowed on him. Of his Biblical counterpart, Noah, we are told that he was “perfect and righteous”—praises that are applied to only one other character in the whole range of Old Testament literature, to wit, Job.[18] But no such encomium is passed on Ut-Napishtim, who, in another version, is designated merely as a “very clever one.”[19]

Had an ethical factor been introduced, in however faint a degree, we should have found a decided modification of the primitive views in regard to the fate of the dead. Perhaps there might have been a development not unlike that which took place among the Hebrews, who, starting from the same point as the Babylonians and Assyrians, reached the conclusion (as a natural corollary to the ethical transformation which the conception of their national deity, Jahweh, underwent) that a god of justice and mercy extended his protection to the dead as well as to the living, and that those who suffered injustice in this world would find a compensatory reward in the next.

Among the Babylonians we have, as the last word on the subject, an expression of sad resignation that man must be content with the joys of this world. Death is an unmitigated evil, and the favour of the gods is shown by their willingness to save the victims as long as possible from the cold and silent grave. A deity is occasionally addressed in hymns as “the restorer of the dead to life,” but only where he saves those standing on the brink of the grave—leading them back to enjoy the warm sunlight a little longer.

The question indeed was raised in Babylonia why after a brief existence man was condemned to eternal gloom? The answer, that is given, is depressing but most characteristic of the arrest in the development of ethical conceptions concerning the gods, in spite of certain appearances to the contrary. The gods themselves are represented, in an interesting tale, based on a nature-myth, as opposed to granting mankind immortal life, and actually having recourse to a deception, in order to prevent another favourite of Ea—the god of humanity—from attaining the desired goal.

The story,[20] as is so frequently the case, is composite. A lament for the disappearance of the two gods of vegetation—Tammuz and Ningishzida[21]—is interlaced with a story of a certain Adapa, who is summoned to appear before Anu, the god of heaven, for having, while fishing, broken the wings of the south-wind, so that for seven days that wind did not blow. At the suggestion of Ea, Adapa dons a mourning garb before coming into the presence of Anu, and is told to answer, when asked why he had done so, that he is mourning for two deities who have disappeared from earth. He is further cautioned against drinking the waters of death, or eating the food of death that will be offered him when he comes before the council of the gods. Adapa faithfully carries out the instructions, but Tammuz and Ningishzida, the guardians at the gate of the heavens, are moved by pity when they learn from Adapa that he is mourning for their own removal from earth, and decide to offer him food of life and water of life. Adapa, ignorant of the substitution, refuses both, and thus forfeits immortal life.

The tale implies that, while Tammuz and Ningishzida are distressed at Adapa’s error, Anu, the head of the pantheon, experiences a sense of relief, in the assurance that man is not destined to receive the boon of the gods—immortality. The tale belongs to the same class as the famous one in the third chapter of Genesis, where, to be sure, Adam[22] is punished for disobedience to the divine command, but there is a decided trace of the belief that the gods do not wish men to be immortal in the fear uttered (Genesis iii., 22) by Jahweh-Elohim that man, having tasted of the tree of knowledge, “may find his way to the tree of life and live for ever.”

The two tales—of Adapa and of Adam—certainly stand in some relation to each other. Both are intended as an answer to the question why man is not immortal. They issue from a common source. The Biblical tale has been stripped almost entirely of its mythical aspects, as is the case with other tales in the early chapters of Genesis which may be traced back to Babylonian prototypes,[23] but the real contrast between the two is the introduction of the ethical factor in the Hebrew version. Jahweh-Elohim, like Anu, does not desire man to be immortal, but the Hebrew writer justifies this attitude by Adam’s disobedience, whereas the Babylonian in order to answer the question is forced to have recourse to a deception practised upon man; Adapa obeys and yet is punished. That is the gist of the Babylonian tale, which so well illustrates the absence of an ethical factor in the current views regarding life after death.

IV

The gods who are placed in control of Aralû partake of the same gloomy and forbidding character as the abode over which they rule. At the head stands the god of pestilence and death, Nergal,[24] identified in astrology with the ill-omened planet Mars, whose centre of worship, Cuthah, became, as we have seen, one of the designations of the nether world. By the side of Nergal stands his consort Ereshkigal (or Allatu)—the Proserpine of Babylonian mythology,—as forbidding in her nature as he is, and who appears to have been, originally, the presiding genius of Aralñ with whom Nergal is subsequently associated.

A myth[25] describes how Nergal invaded the domain of Ereshkigal, and forced her to yield her dominion to him. The gods are depicted as holding a feast to which all come except Ereshkigal. She sends her grim messenger Namtar—that is, the “demon of plague”—to the gods, among whom there is one, Nergal, who fails to pay him a proper respect. When Ereshkigal hears of this, she is enraged and demands the death of Nergal. The latter, undaunted, proceeds to the abode of the angry goddess, encouraged to do so apparently by Enlil and the gods of the pantheon. A gang of fourteen demons, whose names indicate the tortures and misery inflicted by Nergal, accompany the latter. He stations them at the gates of Eresh-kigal’s domain so as to prevent her escape.

A violent scene ensues when Nergal and Ereshkigal meet. Nergal drags the goddess from her throne by the hair, overpowers her, and threatens to kill her. Ereshkigal pleads for mercy, and agrees to share with him her dominion.

Do not kill me, my brother! Let me tell thee something.

Nergal desists and Ereshkigal continues:

Be my husband and I will be thy wife.

I will grant thee sovereignty in the wide earth, entrusting to thee the tablet of wisdom.

Thou shalt be master, and I the mistress.

In this way the myth endeavours to account for the existence of two rulers in Aralu, but one may doubt that a union so inauspiciously begun was very happy.

Another myth, again portraying the change of seasons,[26] describes the entrance of Ishtar, the goddess of vegetation, into the domain of Ereshkigal. The gradual decay of the summer season is symbolised by the piece of clothing, or ornament, which Ishtar is obliged to hand to the guardian at each of the seven gates leading to the presence of Ereshkigal, until, when Ishtar appears at last before her sister, she stands there entirely naked. All trace of vegetation has disappeared, and nature is bare when the wintry season appears and storms set in. In a rage Ereshkigal flies at her sister Ishtar, and orders her messenger Namtar to keep the goddess a prisoner in her palace, from which she is released, however, after some time, by an envoy of Ea. While Ishtar is in the nether world, all life and fertility cease on earth—a clear indication of the meaning of the myth.

The gods mourn her departure. Shamash the sun-god laments before Sin and Ea:

Ishtar has descended into the earth and is not come up.

Since Ishtar is gone to the land of no-return,

The bull cares not for the cow, the ass cares not for the jenny,

The man cares not for the maid in the market[27],

The man sleeps in his place,

The wife sleeps alone.

Ea creates a mysterious being, Asushu-namir,[28] whom he dispatches to the nether world to bring the goddess back to earth. The messenger of Ea is clearly a counterpart of Tammuz, the solar god of the spring, who brings new life to mother earth. Ishtar is sprinkled with the water of life by Asushu-namir and, as she is led out of her prison, each piece of clothing or ornament is returned to her in passing from one gate to the other, until she emerges in all her former glory and splendour. The tale forming originally, perhaps, part of the cult of Tammuz, and recited at the season commemorating the snatching away of the youthful god, illustrates again the hopelessness of escape from the nether world for ordinary mortals. Ishtar can be released from her imprisonment when the spring comes. Tammuz, too, is revived and returns to the world; but alas for mankind, doomed to eternal imprisonment in the “land of no-retum”! The tale ends with a suggestion of hope that “in the days of Tammuz,” that is at the lament for Tammuz (which here assumes the character of a general lament for the dead), the dead, roused by the plaints of the living, may rise and enjoy the incense offered to them—but that is all. They cannot be brought back to earth and sunlight.

The messengers and attendants of Nergal and Ereshkigal are the demons whom we have met in the incantation rituals. They are the precursors of all kinds of misery and ills to mankind, sent as messengers from the nether world to plague men, women, and children with disease, stirring up strife and rivalry in the world, separating brother from brother, defrauding the labourer of the fruits of his labour, and spreading havoc and misery on all sides; depicted as ferocious and terrifying creatures, ruthless and eternally bent on mischief and evil. The association of these demons with the world where no life is, further emphasises the view held of the fate of the dead. With such beings as their gaolers what hope was there for those who were imprisoned in the great cavern? If conscious of their state, as they appear to have been, what emotion could they have but that of perpetual terror?

The absence of the ethical factor in the conception of life after death, preventing, as we have seen, the rise of a doctrine of retribution for the wicked, and belief in a better fate for those who had lived a virtuous and godly life, had at least a compensation in not leading to any dogma of actual bodily sufferings for the dead. The dead were at all events secure from the demons who came up to plague the living, but whose duty so far as the dead were concerned seemed to be limited to keeping the departed shades in their prison. Nor did the gods of the upper world concern themselves with the dead, and while in the descriptions of Nergal and Ereshkigal and their attendants we have all the elements needed for the revelation of the tortures of hell, so vividly portrayed by Christian and Mohammedan theologians, so long as Aralū remained the abode of all the dead, it was free from the cries of the condemned—a gloomy but a silent habitation. A hell full of tortures is the counterpart of a heaven full of joys. The Babylonian-Assyrian religion had neither the one nor the other; and the natural consequence was the doctrine that what happiness man may desire must be secured in this world. It was now or never.

This lesson is actually drawn in a version of the Gilgamesh epic,[29] which, be it remembered, dates from the period of Hammurapi. The hero, smitten with disease and fearing death, is discouraged by the gods themselves in his quest of life, and in his desire to

escape the fate of his companion Enkidu.[30] Shamash, the sun-god, tells him:

Gilgamesh, whither hurriest thou?

The life that thou seekest thou wilt not find.

Sabitu, a maiden, dwelling on the seacoast, to whom Gilgamesh goes, tells him the same. In reply to the following greeting of the hero:

Now, O Sabitu, that I see thy countenance,

May I not see death which I fear!

Sabitu imparts to him a guidance for life:

Gilgamesh, whither hurriest thou?

The life that thou seekest thou wilt not find.

When the gods created man,

They fixed death for mankind.

Life they took in their own hand.

Thou, O Gilgamesh, let thy belly be filled!

Day and night be merry,

Daily celebrate a feast,

Day and night dance and make merry!

Clean be thy clothes,

Thy head be washed, bathe in water!

Look joyfully on the child that grasps thy hand,

Be happy with the wife in thine arms!

This is the philosophy of those whom Isaiah (xxii., 13) denounces as indifferent to the future:

“Let us eat and drink, for to-morrow we must die.”

Like an echo of the Babylonian poem the refrain of Ecclesiastes rings in our ears:[31]

There is nothing better for a man than that he should eat, and that his soul should enjoy his labour.

“All go to one place,” says Ecclesiastes (iii., 20).

“All are of the dust and all turn to dust. Vanity, vanity—all is vanity.”

Almost the very words of the Babylonian poem are found in a famous passage of Ecclesiastes (ix., 7-9):

Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy and drink thy wine with a merry heart. Let thy garments be always white, and let thy head not lack ointment. Live joyfully with thy wife whom thou lovest, all the days of thy life of vanity which he has given thee under the sun—for this is thy portion.[32]

The pious Hebrew mind found the corrective to this view of life in the conception of a stern but just god, acting according to self-imposed standards of right and wrong, whose rule extends beyond the grave. This attitude finds expression in the numerous additions that were made to Ecclesiastes in order to counteract the frankly cynical teachings of the original work, and to tone down its undisguised skepticism.

“Know,” says one of these glossators,

“that for all these things God will bring thee unto judgment” (xi., 9).

“The conclusion of the whole matter,” says another,

“A good name,” says a third,

“is better than precious ointment” (vii., i).[33]

Ethical idealism, by which is here meant a high sense of duty and a noble view of life, is possible only—so it would seem—under two conditions, either through a strong conviction that there is a compensation elsewhere for the wrongs, the injustice, and the suffering in this world, or through an equally strong conviction that the unknown goal toward which mankind is striving can be reached only by the moral growth and ultimate perfection of the human race— whatever the future may have in store. The ethics of the Babylonians and Assyrians did not look beyond this world, and their standards were adapted to present needs and not to future possibilities. The thought of the gloomy Aralu in store for all coloured their view of life,—not indeed in leading them to take a pessimistic attitude towards life, or in regarding this world as a vale of tears, but in limiting their ethical ideals to what was essential to their material well-being and mundane happiness.

V

It would be an error, however, to infer that such a view of life is incompatible with relatively high standards of conduct. That is far from being the case—at least in Babylonia and Assyria. Even though the highest purpose in life was to secure as much joy and happiness as possible, the conviction was deeply ingrained, particularly in the minds of the Babylonians, that the gods demanded adherence to moral standards. We have had illustrations of these standards in the incantation texts,[34] where by the side of ritualistic errors we find the priests suggesting the possibility that misfortune has been sent in consequence of moral transgressions—such as lying, stealing, defrauding, maliciousness, adultery, coveting the possessions of others, unworthy ambitions, injurious teachings, and other misdemeanours. The gods were prone to punish misdoings quite as severely as neglect of their worship, or indifference to the niceties of ritualistic observances.

The consciousness of sinful inclinations and of guilt, though only brought home to men when misfortunes came or were impending, was strong enough to create rules of conduct in public and private affairs that rested on sound principles. The rights of individuals were safeguarded by laws that strove to prevent the strong from taking undue advantage of the weak. Business was carried on under the protection of laws and regulations that impress one as remarkably equitable. Underhand practices were severely punished, and contracts had to be faithfully executed. All this, it may be suggested, was dictated by the necessities of the growth of a complicated social organisation. True, but what is noticeable in the thousands of business documents now at our behoof and covering almost all periods from the earliest to the latest, is the spirit of justice and equity that pervades the endeavour to regulate the social relations in Babylonia and Assyria.[35] This is particularly apparent in the legal decisions handed down by the judges, of which we have many specimens.[36]

As a protection to both parties engaging in business transactions, a formal contract wherein the details were noted was drawn up, and sealed in the presence of witnesses. This method was extended from loans and sales to marriage agreements, to testaments, to contracts for work, to rents, and even to such incidents as engaging teachers, and to apprenticeship. The general principle, already implied in the Hammurapi Code, and apparently in force at all periods, was that no agreement of any kind was valid without a duly attested written record. The religious element enters into these business transactions in the oath taken in the name of the gods, with the frequent addition of the name of the reigning king by both parties as a guarantee of good faith. In some cases the oath is, in fact, prescribed by law.

If a dispute arose in regard to the terms of a contract, and no agreement could be reached by the contracting parties, the case was brought before the court, which appears to have been ordinarily composed of three judges, as among the Jews (whose method of legal procedure was largely modelled upon Babylonian prototypes). All the documents in the case had to be brought into court, and each party was obliged to bring witnesses to support any claims lying outside the record. The impression that one receives from a study of these decisions is that they were rendered after a careful and impartial consideration of the documents, and of the statements of the parties and of previous decisions.

An example taken from the neo-Babylonian period[37] will illustrate the spirit by which the judges were actuated in deciding the complicated cases that were frequently brought before them. It is the case of a widow Bunanit, who brings suit to recover property, devised to her by her husband, which has been claimed by her brother-in-law.

Her case is stated in detail:

Bunanit, the daughter of Kharisā, declared before the judges of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, as follows: “Apil-addunadin, son of Nikbadu,” took me to wife, receiving three and a half manas of silver as my dowry, and one daughter I bore him. I and Apil-addunadin, my husband, carried on business[38] with the money of my dowry, and bought eight GI[39] of an estate in the Akhula-galla quarter of Borsippa,[40] for nine and two thirds manas of silver,[41] besides two and a half manas of silver which was a loan from Iddin-Marduk, son of Ikischa-aplu, son of Nur-Sin, which we added to the price of said estate and bought it in common.[42]

“In the fourth year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, I put in a claim for my dowry against my husband Apil-addunadin, and of his own accord he sealed over to me the eight GI of said estate in Borsippa and transferred it to me for all time,[43] and declared on my tablet[44] as follows:

‘21/2manas of silver which Apil-addunadin and Bunanit borrowed from Iddin-Marduk and turned over to the price of said estate they held in common,[45] That tablet he sealed and wrote the curse of the gods on it.’[46]

“In the fifth year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, I and my husband Apil-addunadin adopted Apil-adduamara as son,[47] and made out the deed of adoption,[48] stipulating two manas and ten shekels of silver and a house-outfit as the dowry of Nubta, my daughter. My husband died, and now Aḳabi-ilu, son of my father-in-law,[49] has put in a claim for said estate and all that has been sealed and transferred to me, including Nebo-nūr-ili whom we obtained[50] from Nebo-akh-iddin. Before you I bring the matter. Render a decision.”

The case has been stated with great clearness. The legal point involved, because of which the brother-in-law puts in a claim on behalf of the deceased husband’s family, turns on the question whether the wife is entitled to the entire estate, seeing that her original dowry was only three and one half manas, or, in other words, whether the husband had a right to turn over to her the whole property on the ground that it was her dowry which, through business transactions conducted in common, had increased to nine and two thirds manas. Bunanit, in stating her case, lays great stress, it will be observed, on the circumstance that she and her husband did all things in common —bartered in common, bought in common, borrowed in common, adopted a son in common, and acquired a slave in common.

The decision rendered by the judges is remarkably just, manifesting a due regard for the ethics of the situation, and based on an examination of the various documents or tablets in the case and which in such an instance had to be produced.

The document continues as follows:

The judges heard their complaints,[51] and read the tablets and contracts which Bunanit[52] had laid before them. To Aḳabi-ilu they grant nothing of the estate in Borsippa, which in lieu of her dowry had been transferred to Bunanit, nor Nebo-nftr-ili, whom she and her husband had bought, nor any of the property of Apil-addunadin. They confirmed the documents of Bunanit and Apil-adduamara.

The sum of two and one half manas of silver is to be returned forthwith to Iddin-Marduk who had advanced it for the sale of the house. Then Bunanit is to receive three and one half manas of silver—her dowry—and a share of the estate. Nebo-nūr-ili is given to Nubta in accordance with the agreement of her father.[53]

The names of the six judges through whom the said decision was rendered are then given, followed by the names of two scribes and the date

Babylon, 26th of Ulul (6th month), 9th year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon.[54]

The balance of the estate evidently passed over to the adopted son. Bunanit won her case against her brother-in-law, but it looks on the surface as though she had not won all that she had claimed. The judges practically ignored the transfer of the entire estate to her, for they granted her merely her dowry and the share of her husband’s property to which as widow she was entitled. Had there not been an adopted son, the claim of Aḳabi-ilu would probably have been upheld for the balance of the estate, exclusive of the slave. Bunanit is obliged to confess that her husband transferred the property “of his own accord,” which means that it was not upon an order of the court, and therefore not legally-established. It is safe to assume that the court would not have regarded such a transaction as legal, for despite the fact that the pair do not adopt a son until after the transfer, the judges allowed the widow her dowry only and her share of the estate. On the other hand, though it might appear that, as a partner, Bunanit would only have been responsible for one half of the amount borrowed from Iddin-Marduk, the judges, by ignoring the transfer, could order that Iddin-Marduk must be paid in full out of the property left by Apil-addunadin.

VI

The kings themselves, although not actuated, perhaps, by the highest motives, set the example of obedience to laws that involved the recognition of the rights of others. From a most ancient period there is come down to us a remarkable monument recording the conveyance of large tracts of land in northern Babylonia to a king of Kish, Manishtusu,[55] (ca . 2700 B.C.), on which hundreds of names are recorded from whom the land was purchased, with specific descriptions of the tracts belonging to each one, as well as the conditions of sale. The king here appears with rights no more exclusive or predominant than those of a private citizen. Not only does he give full compensation to each owner, but undertakes to find occupation and means of support for fifteen hundred and sixty-four labourers and eighty-seven overseers, who had been affected by the transfer.

The numerous boundary stones that are come down to us (recording sales of fields or granting privileges), which were set up as memorials of transactions, are silent but eloquent witnesses to the respect for private property. The inscriptions on these stones conclude with dire curses in the names of the gods against those who should set up false claims, or who should alter the wording of the agreement, or in any way interfere with the terms thereon recorded. The symbols of the gods[56] were engraved on these boundary stones as a precaution and a protection to those whose rights and privileges the stone recorded. The Babylonians could well re-echo the denunciations of the Hebrew prophets against those who removed the boundaries of their neighbours’ fields. Even those Assyrian monarchs most given to conquest and plunder boast, in their annals, of having restored property to the rightful owners, and of having respected the privileges of their subjects and dependents.

For instance, Sargon of Assyria (721-705 B.C.), while parading his conquests in vain-glorious terms, and proclaiming his unrivalled prowess, emphasises[57] the fact that he maintained the privileges of the great centres of the south, Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon, and that he protected the weak and righted their injuries. His successor Sennacherib[58] claims to be the guardian of justice and a lover of righteousness. Yet, these are the very same monarchs who treated their enemies with unspeakable cruelty, inflicting tortures on prisoners, violating women, mutilating corpses, burning and pillaging towns.

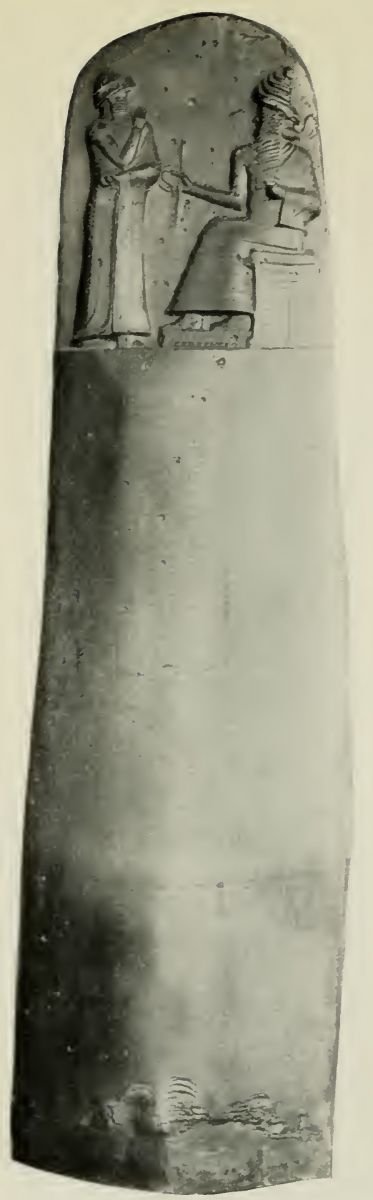

More significant still is the attitude of a monarch like Hammurapi, who, in the prologue and epilogue to his famous Code, refers to himself as a “king of righteousness,” actuated by a lofty desire to protect the weak, the widow, and the orphan. In setting up copies of this Code in the important centres of his realm, his hope is that all may realise that he, Hammurapi , tried to be a “father” to his people. He calls upon all who have a just cause to bring it before the courts, and gives them the assurance that justice will be dispensed,—all this as early as nigh four thousand years ago!

On a tablet[59] commemorative of the privileges accorded to Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon—to which, we have just seen, Sargon refers in his annals—there are grouped together, in the introduction, a series of warnings, which may be taken as general illustrations of the principles by which rulers were supposed to be guided:

If the king does not heed the law, his people will be destroyed; his power will pass away.

If he does not heed the law of his land, Ea, the king of destinies, will judge his fate and cast him to one side.

If he does not heed his abkallu,[60] his days will be shortened.

If he does not heed the priestess [?], his land will rebel against him.

If he gives heed to the wicked, confusion will set in.

If he gives heed to the counsels of Ea, the great gods will aid him in righteous decrees and decisions.

If he oppresses a man of Sippar and perverts justice, Shamash, the judge of heaven and earth, will annul the law in his land, so that there will be neither abkallu nor judge to render justice.

If the Nippurians are brought before him for judgment, and he oppresses them with a heavy hand, Enlil, the lord of lands, will cause him to be dispatched by a foe and his army to be overthrown; chief and general will be humiliated and driven off.

If he causes the treasury of the Babylonians to be entered for looting, if he annuls and reverses the suits of the Babylonians, then Marduk, the lord of heaven and earth, will bring his enemy against him, and will turn over to his enemy his property and possessions.

If he unjustly orders a man of Nippur, Sippar, or Babylon to be cast into prison, the city where the injustice has been done, will be made desolate, and a strong enemy will invade the prison into which he has been cast.

In this strain the text proceeds; and while the reference is limited to the three cities, the obligations imposed upon the rulers to respect privileges once granted may be taken as a general indication of the standards everywhere prevailing. We must not fail, however, to recognise the limitation of the ethical spirit, manifest in the threatened punishments, should the ruler fail to act according to the dictates of justice and right. For all this, whether it was from fear of punishment, or desire to secure the favour of the gods, the example of their rulers in following the paths of equity and in avoiding tyranny and oppression must have reacted on their subjects, and incited them to conform their lives to equally high standards.

There is extant a text—unfortunately preserved only in part—which, somewhat after the manner of the Biblical “Book of Proverbs,” lays down certain moral precepts that were intended to be of general application. That it is a fragment, and an Assyrian copy of an older text, suggests an inference that there may have been similar and even more extensive collections; and, perhaps, some fortunate chance will bring to light more texts among the archives of Babylonian temples, from which the texts of Ashur-banapal’s library were for the most part copied.[61]

The fragment, which may be taken as a fair example of the ethical teachings prescribed by the priests, reads as follows:[62]

Thou shalt not slander—speak what is pure!

Thou shalt not speak evil—speak kindly!

He who slanders (and) speaks evil,

Shamash[63] will visit recompense on his head.

Let not thy mouth boast—guard thy lip!

When thou art angry, do not speak at once!

If thou speakest in anger, thou wilt repent afterwards,

And in silence sadden thy mind.

Daily approach thy god,

With offering and prayer as an excellent incense!

Before thy god (come) with a pure heart,

For that is proper towards the deity!

Prayer, petition, and prostration,

Early in the morning shalt thou render him;

And with god’s help, thou wilt prosper.

In thy wisdom learn from the tablet.[64]

The fear (of god) begets favour,

Offering enriches life,

And prayer brings forgiveness of sin.

He who fears the gods, will not cry [in vain(?)].

He who fears the Anunnaki,[65] will lengthen [his days].

With friend and companion thou shalt not speak [evil (?)].

Thou shalt not say low things, but (speak) kindness.

If thou promisest, give [what thou hast promised (?)].

. . . . . . . .

Thou shalt not in tyranny oppress them,

For this his god will be angry with him;

It is not pleasing to Shamash—he will requite him with evil.

Give food to eat, wine to drink.

Seek what is right, avoid [what is wrong (?)].

For this is pleasing to his god;

It is pleasing to Shamash—he will requite him [with mercy].

Be helpful, be kind [to the servant(?)].

The maid in the house thou shalt [protect (?)].

Brief as the fragment is, it covers a large proportion of the relations of social life. The advice given is largely practical, and the reward offered is ever of this world—long life, happiness, freedom from misfortune—while errors, be they moral or ritualistic, bring their own punishment with them. The ethics taught is not of a kind to carry us upward into higher regions, and the nearest approach to a nobler touch is in the inculcation of the proper attitude toward the gods, and of kindness and mercy toward fellow-men; but in spite of these obvious limitations, the ethical standards in the precepts show that it was considered, at least, the part of wisdom to maintain a clean morality. Worldly wisdom takes the precedence throughout in popular maxims and sayings, and it is from this point of view that we must consider such a text as the present one. Wholesome teachings, even where the motives enjoined are not of the highest, may yet point to sound moral foundations and indicate that the ethical sense has had its awakening. A nobler height may be gained in course of time.

VII

The spirit of Hammurapi’s Code further illustrates the ethical standards imposed alike upon rulers, priests, and people. The business and legal documents of Babylonia and Assyria show that the laws, codified by the king, and representing the summary of legal procedures and legal decisions down to his day, were not only enforced but interpreted to the very letter. To be sure, the Code embodies side by side enactments of older and later dates. It contains examples of punishment by ordeal, as, e.g., in the case of a culprit accused of witchcraft,[66] where the decision is relegated to the god of the stream into which the defendant is cast. If the god of the stream takes him unto himself, his guilt is established. If the god by saving him declares his innocence, the plaintiff is put to death and his property forfeited for the benefit of the defendant, wrongfully accused.

The lex talionis —providing “eye for eye, bone for bone, and tooth for tooth”—also finds a place in the Code;[67] but in both the ordeal and in the lex talionis, it does not differ from the Pentateuchal Codes, which, likewise compilations of earlier and later decrees, prescribe the ordeal[68] in the case for instance of the woman accused of adultery; and if it be maintained that the principle of “eye for eye and tooth for tooth” is set up in the Old Testament[69] merely as a basis for a compensation equal to the injury done, the same might hold good for the Ham-murapi Code and with even greater justification, since the Code actually limits the lex talionis to the case of an injury done to one of equal rank, while in the case of one of inferior or superior rank, a fine is imposed, which suggests that the lex talionis as applied to one of equal rank has become merely a legal phrase to indicate that a return, equal to the value of an eye or a tooth to him who suffers the assault, is to be imposed.

This, of course, is a mere supposition, but at all events the underlying principle is one of equal compensation, and in so far it is ethical in its nature. On the other hand, there can be no doubt that the original import of the lex talionis , among both Babylonians and Assyrians (as among the Hebrews), involved a literal interpretation, as may be concluded from the particularly harsh and inconsequent application to the case of the son of a builder, who is to be put to death should an edifice, erected by his father, fall and kill the son of the owner.[70]

Another unfavourable feature of the Code, which illustrates the limitations of ethical principles, lies in the extreme severity of many of its punishments. The penalty of death is imposed for about fifty offences, some of them comparatively trivial, such as stealing temple or royal property,[71] where, however, the element of sacrilege enters into consideration. Even the claimant of a property, alleged to have been purchased from a man’s son or servant, or of a member of the higher class, who is unable to show the contract, is held to be a thief, because of the fraudulent intent, and is put to death.[72] The law is, however, fair in its application, and punishes with equal severity, when there is a fraudulent attempt to deprive one of legally acquired property. He who aids a runaway slave is placed in the same category[73] as he who steals a minor son,[74] or as he who conspires to take property away from his neighbour, and is put to death for the fraudulent attempt. A plunderer at a fire is himself thrown into that fire,[75] and he who has broken into a man’s house is immured in the breach that he himself has made.[76]

In cases of assault and battery, a distinction is drawn according to the rank of the assailant and the assailed. If a person of lower rank attacks a person of higher rank, the punishment is a public whipping of sixty lashes with a leather thong,[77] whereas if the one attacked is of equal rank, the whipping is remitted, but a heavy fine— one mana of silver[78]—is imposed. If a slave commits this offence, and the victim is of high rank, the slave’s ear is cut off [79] At the same time, an ethical spirit is revealed in the stipulation that, if the injury be inflicted in a chance-medley, and the blow not intentionally aimed at any particular person, the offender is discharged with the obligation to pay the doctor’s bill,[80] or, in the event of the death of the victim, with a fine according to the rank of the deceased.[81] A lower level of equity is, however, represented by the enactments that, in case a man shrikes a pregnant woman and the woman dies, a daughter of the offender is put to death,[82] or in case a surgical operation on the eye is not successful, and the patient loses his eye, the surgeon’s hand is to be cut off,[83] or in the event of the death of a slave under an operation, the surgeon must reimburse the owner by giving him another slave.[84]

All such laws are variations of the lex talionis , and unquestionably reflect a primitive form of social organisation, where advanced ethical principles are not to be expected. They must be regarded in the same light as many of the enactments in the Pentateuchal Codes and in other collections of ancient laws— as survivals indeed of even earlier regulations which, having been once accepted, were faithfully incorporated in the compilation made by Hammurapi, whereof the aim clearly was to furnish a complete survey of regulations for the execution of justice.

These crude statutes, therefore, constitute a valuable testimony to the process of development which led to the higher conditions that characterise the Code in general. This superior level is reached, e.g., in the provision that a judge who has rendered a wrong decision is to pay a fine twelve-fold the amount involved in the suit; and in addition, he is to be removed from the bench and never again to be permitted to exercise the judicial function.[85] This regulation recognises a fundamental principle of justice that he who dispenses it must be beyond suspicion, and must be familiar also with the law to be administered. No distinction is made between a judicial error due to ignorance, and one due to improper motives on the part of the judge. He is not to change his mind, and it is assumed that if he has made an unintentional error, he has shown himself to be as unfit as though the erroneous decision had been prompted by maliciousness or a wilful disregard of justice.

The judge stands in the place of deity according to the general view prevailing in antiquity. If he fail in the proper discharge of his duties, he lowers the dignity of his office; and the deity, by permitting him to go astray, shows that he no longer desires the judge to speak in his name. Confidence in the probity and ability of the judge is the conditio sine qud non of the execution of justice. Defective as this uncompromising attitude toward a judicial error may be from a modern standpoint in not recognising an appeal from a lower to a higher court, the ethical basis is both sound and of a high order. With such a provision, which speaks volumes for the standards obtaining in the days of Hammurapi, the integrity of the courts was firmly secured for all time. Equally noteworthy and more modern in its spirit is the provision that a false witness, whose testimony jeopardises the life of another, shall be put to death.[86] One is reminded of the Venetian law quoted by Portia that the life of him who places a citizen in jeopardy “lies in the mercy of the Duke only, ’gainst all other voice.”[87] If the false testimony involves property, the false witness must pay the amount involved in the suit.

Passing to more specific subjects, the regulation of family affairs and of commerce may be regarded as a safe index of the standards set up for private and public ethics. No less than sixty-eight[88] of the two hundred and seventy-two paragraphs or sections into which the Code may be divided, or just one fourth, deal on the one hand with the relation of husband and wife, and on the other of parents and children. This proportion is in itself a valuable indication of the importance in the social organisation attached to the family. The general aim of the laws may be summed up in the statement that they are to ensure the purity of family life. The law is severe against the faithless wife—mercilessly severe, condemning her and the adulterer to death by drowning,[89] but it also protects her against false accusations. He who unjustly points the finger of suspicion against a woman— be she a wife, or a virgin who has taken a vow of chastity—is to be publicly humiliated by having his forehead branded.[90] Even the husband must substantiate the charge against his wife, and the wife can free herself from suspicion by an oath,[91] though, if the actual charge is brought by another than her husband, she must submit, at the husband’s instance, to the same ordeal of the river god[92] as the one accused of witchcraft. But even if the charge be substantiated, the husband may exercise the right of possession and allow his wife to live; and the king also may grant mercy to the male offender.[93]

As a protection to the wife, a formal marriage contract must be drawn up, as is not infrequent in our days. A marriage without a contract is void.[94] A woman betrothed to a man is regarded as his wife, and in case she is disgraced by another, the offender is put to death;[95] from which we may perhaps be permitted to conclude that if she be not betrothed, the offender is obliged to marry her. The Code still recognises the wife as an actual possession of her husband, but, on the other hand, if he fails to provide for her support, she may leave him. A fine distinction is made between actual desertion or enforced absence on the part of the husband. In the former case,[96] the woman has the right to marry another, and her husband on his return not only cannot force her to return to him, but she is not permitted to do so. On the other hand, if her husband is taken prisoner and no provision has been made for her sustenance, she may marry another, but on her husband’s return he may claim her, though the children bom in the interim belong to the actual father.[97]

Inasmuch as the wife forms part of her husband’s chattels, divorce lies, of course, at the option of the husband, but he cannot sell his wife, and, if he dismisses her, she is to receive again her marriage portion. Alimony was allowed for her own needs and those of her children, whose rearing was committed to her.[98] When the children reach their majority, a portion of their inheritance must be given to the mother. Even in the case of a wife who has not borne her husband any children, he may not dismiss her without giving her alimony and returning her dowry,[99] but if she has neglected her husband’s household, and as the law expresses it, has committed “indiscretions,” he may send her away without any compensation or may even keep her as a slave, while he is free to marry another woman as his chief wife.[100] The dawning at least of the wife’s liberty is to be seen in the provision that, if a woman desires to be rid of her husband, and provided on examination it is shown that she has good cause—the legal language implies a neglect of marital duties on the husband’s part,—she may return to her father’s house, and be entitled to her marriage portion.[101]

The prevailing custom in Babylonia at the time of Hammurapi was monogamy, but it was still permissible, as a survival of former conditions, for a man to take a concubine, or the wife could give her husband a handmaid[102]—as Sarah gave Hagar to Abraham (Genesis xvi., i, 2), in order that he might have children by her. The Code endeavours, while recognising conditions that are far from ideal, so to regulate these conditions as to afford protection to the legitimate wife. It is provided that, in case the maid-servant has borne children, the husband may not take an additional concubine.[103] It would, furthermore, appear that a second wife may be taken into the home only in the event that the marriage with the first spouse is without issue.[104] Even then, the first wife is protected by the express stipulation that she shall retain her place at the head of her husband’s household. The manifest purpose of such regulations is to pave the way for passing beyond former crude conditions, such for example as are described in Genesis as existing in Hebrew society in the days of the patriarchs. Old laws are rarely abrogated—they are generally so modified as to lose their original force. Perhaps the most significant of these marriage-laws is the stipulation that the woman who is smitten with an incurable disease—the term used may have reference to leprosy—must be taken care of by her husband as long as she lives. In no circumstances, it is added, can he divorce her, and if she prefer to return to her father’s home, he must give her dowry to her.[105]

Legal rights are assured to a woman even after her husband’s death. Her children have no claim on property given to her by her husband. She may dispose of such property to a favourite child but, on the other hand, she is restrained from passing it on to her brother, which would take it out of her husband’s clan.[106] Finally, there is a touch almost modem in the law that a wife cannot contract obligations in her husband’s name, nor can he be held responsible for debts thus contracted.[107] The interesting feature of the provision is that it points to the independent legal status acquired by woman, who, as we learn also from business and legal documents, could own property in her own right, borrow money and contract debts independently, as long as she did not involve her husband’s property, and could appear as a witness in the courts. The dowry of a wife who dies without issue reverts to her father’s estate.[108]

That the laws against incest are most severe is perhaps not to be taken as an index of advanced moral standards, for we find such regulations even in primitive society where, while promiscuous intercourse with unmarried women is permitted, the severe taboo imposed upon a wife[109] is extended to every kind of incestuous relations. The Hammurapi Code ordains that a father who has been intimate with his daughter is to be banished from the city,[110] which means that he loses his position and rights of citizenship. If he enters into intimate relations with his daughter-in-law, he is to be strangled, and the woman is to be thrown into the water.[111] If this take place after betrothal but before the actual marriage, the father is let off with a heavy fine and the woman may marry whom she pleases.[112] When a son is intimate with his mother, both are burned.[113]

It also betokens an advanced stage of society that a man can legitimatise the children born of his wife’s handmaid, and they then receive equal portions of the estate with the children of the legitimate wife;[114] but even if he fail to legitimatise such children, they must be set free after his death. The legitimate children have no claim upon their half-brothers and half-sisters born out of wedlock.[115] Not only the wife but also the widow is amply protected by the Code, through the stipulation that a share of her husband’s estate belongs to her in her own right and name. She is to remain in her husband’s house, and if the children maltreat her, the courts may impose punishment upon them. If, however, of her own accord the widow leaves her husband’s house, then she is naturally entitled to her own dowry only, and not to any share in her husband’s estate; but, on the other hand, she is free in that case to marry whomsoever she pleases.[116] Daughters are given a share in their father’s estate, and this is extended even to those who as priestesses have taken the vow of chastity. Such nuns have a right to their dowry, which they can dispose of as they see fit, but their share of the paternal estate cannot be disposed of by them. On the death of a nun, her share reverts to her brothers or to their heirs.[117]

Lastly, as an interesting example of an older law, dating from the period when a man could dispose of his wife and children as he disposed of his chattels and possessions, but so modified as to be practically abrogated, we may instance the provision that, if a man pledges, or actually sells his wife and children for his debts, the creditor can claim them for three years only. In the fourth year they must be set free.[118] This stipulation assumes an older law, according to which a man could sell his wife and children without condition. Instead of revoking the law (which, as has been pointed out, is not the usual mode of procedure in ancient legislation), the limitation of three years is inserted, and this changes the sale into a lease. We have a parallel in the Book of the Covenant (Exodus xxi., 2) which provides that a Hebrew slave must be set free after six years. This is practically an abrogation of slavery[119] by converting it into a lease for a limited period.

Coming to the commercial regulations of the Code, the fundamental principle underlying them is the fixing of responsibility where it belongs, and the protecting of both parties to a transaction not only against fraud on either side, but also against unforeseen circumstances. It is somewhat significant that, although many of the laws deal with cases of wilful fraud or deceit in one party, the general assumption is that both parties are actuated by honest motives, and that difficulties often arise through no fault of either, being due to the growing complications of business activities. As a protection to buyer and seller or to any two contracting parties, it is stipulated that there must be a written contract in the presence of witnesses. No claim can be made unless a contract can be found, and the assumption is that failure to produce witnesses in case of a claim is proof of attempted fraud. An interesting case is mentioned in a series of paragraphs,[120] of one who asserts that he has lost an article belonging to him, which he finds in the possession of another, which, however, the latter maintains that he has bought.

The point is to find the guilty party. The purchaser must bring into court the vendor and witnesses to the sale, and he who claims the property must bring witnesses to establish his claim. If both sets of witnesses appear and their testimony is shown to be true, the vendor of the property adjudged to be lost is revealed as the thief and is put to death, this severer punishment being inflicted because the aggravating factor of fraud is added to theft. The article is restored to the lawful owner, and the innocent purchaser is compensated out of the estate of the thief and fraudulent vendor. If the purchaser fail to produce the vendor and witnesses to the sale, and the claimant brings witnesses to prove his property, then the purchaser is put to death as the real thief, and the stolen article is restored to its lawful owner. If, on the other hand, the claimant cannot bring witnesses to prove his property, then he is considered to have made a fraudulent claim, and suffers the penalty of death. If the vendor—prove to be such—has meanwhile died, the amount is nevertheless to be restored to the purchaser out of the estate of the vendor. Finally, the law allows a term of six months within which to produce the witnesses in case they are not at once accessible.

The farming of lands for the benefit of temples or for lay owners, with a return of a share of the products to the proprietors, was naturally one of the most common commercial transactions in a country like the Euphrates Valley, so largely dependent upon agriculture. Complications in such transactions would naturally ensue, and it is interesting to observe with what regard for the ethics of the situation they are dealt with in the Code. If a tenant fail to produce a crop through his own fault, he is obliged, of course, to reimburse the proprietor, and as a basis of compensation, the yield of the adjoining fields is taken as a standard.[121] If he have failed, however, to cultivate the field, he is not only obliged to compensate the owner according to the proportionate amount produced in that year in adjoining fields, but must, in addition, plough and harrow the property before returning it to the owner, besides furnishing ten measures—about twenty bushels—of grain for each acre of land.[122]

In case of a failure of the crops, or a destruction by act of God, no responsibility attaches to the tenant,[123] but if the owner had already received his share beforehand, and then through a storm or an inundation the yield is spoiled, the loss must be borne by the tenant.[124] In subletting the tilling of fields as part payment for debt, it is stipulated that the original proprietor must first be settled with, and after that the second lessee, who shall receive in kind the amount of his debts plus the usual interest[125]. The ethical principle is, therefore, similar to that applying in our own days to first and second mortgages.

The owner of a field is responsible for damage done to his neighbours’ property through neglect on his part—for example, through his failure to keep the dikes in order, or through his cutting off the water supply from his neighbour.[126] A shepherd who allows his flocks to pasture in a field without permission of the owner is fined to the extent of twenty measures of grain for each ten acres. What is left of the pasturage also belongs to the owner.[127] The same care, with due regard to the ethics of the situation, is exercised in regulating the relation between a merchant and his agent. The latter is, of course, responsible for goods entrusted to him, including damage to them through his fault, but if they are stolen or forcibly taken from him—after swearing an oath to that effect—he is free from further responsibility.[128] Neglect to carry out instructions in connection with a commission entails a fine threefold the value involved,[129] but, on the other hand, if the merchant tries to defraud his agent, he pays a fine of sixfold the amount involved.[130]

According to the ethical principles governing the Code, the directors of a bank would be responsible to the depositors for losses incurred through the business transactions of the bank. The protection of the debtor in business transactions against the tyranny of the creditor is carried almost to an extreme; it would appear that the creditor cannot attach the property of his debtor without obtaining the authority of the court; and if. e. g., he has helped himself from the granary of the debtor without the latter’s permission, although he may not have taken more than the amount of the debt, he must return what he has taken, and by his wilful act forfeits his original claim.[131] The courts[132] regulated the hire of cattle for ploughing or other purposes, the wages of mechanics and labourers, the hire of ships for freight, the amount of the return for the farming of fields, and even the fee of surgeons for operations[133]—all with a view to affording protection against both extortion and underpayment.

VIII

There is, of course, also another side to the picture. The internal conditions of Babylonia and Assyria were at all times, naturally, far from ideal. The people, as a whole, bad no share in the government, and, as we have seen, only a limited share in the religious cult, which was largely official and centred around the general welfare and the well-being of the king and his court. Slavery continued in force to the latest days, and, though slaves could buy their freedom and could be adopted by their masters, and had many privileges, even to the extent of owning property and engaging in commercial transactions, yet the moral effect of the institution in degrading the dignity of human life, and in maintaining unjust class distinctions was none the less apparent then than it has been ever since. The temples had large holdings which gave to the religious organisation of the country a materialistic aspect, and granted the priests an undue influence.

Political power and official prestige were permanently vested in the rulers and their families and attendants. We hear, occasionally, of persons of humble birth rising to high positions, but the division of the classes into higher and those of lower ranks was on the whole rigid. Uprisings were not infrequent both in Babylonia and Assyria, and internal dissensions, followed by serious disturbances, revealed the dissatisfaction of the majority with the yoke imposed upon them, which, especially through enforced military service and through taxes for the maintenance of temples, armies, and the royal court, must often have borne heavily on them. The cruelties, practised especially by the Assyrian rulers in times of war, must also have reacted unfavourably on the general moral tone of the population.

But such conditions prevailed everywhere in antiquity; nor would it be difficult to parallel them in much later ages, and even among some of the leading nations of modern times. The general verdict in regard to the ethics of the Babylonians and Assyrians need not, therefore, be altered because of the shadows that fall on the picture that has been unrolled. A country that offers protection to all classes of its population, that imposes responsibilities upon husbands and fathers, and sees to it that those responsibilities are not evaded, that protects its women and children, that in short, as Hammurapi aptly puts it, aims to secure the weak against the tyranny of the strong and to mete justice to all alike, may fairly be classed among civilisations which, however short they may fall of the ideal commonwealth, yet recognise obedience to ethical principles as the basis of well-being, of true culture, and of genuine religion.

And yet how harsh is the judgment passed by the Hebrew prophets and psalmists on both Babylonia and Assyria! Prophet and religious poet unite in accusing them of the most terrible crimes; they exhaust the Hebrew vocabulary in pronouncing curses upon Assyria and Babylonia. All nature is represented as rejoicing at their downfall, and it has often been remarked that the prediction that jackals and hyenas would wander through the ruins of Assyria’s palaces and Babylonia’s temples has been fulfilled almost to the letter. The pious Jews of later ages saw the divine punishment sent for the many crimes of these empires of the East, in the obliteration of the vast cities of the Euphrates Valley and the region to the north, until their very foundation stones were forgotten.[134]

It was natural that to the Hebrew patriots Assyria and Babylonia should appear to be the embodiment of all evils; was it not through Assyria that Israel fell, and through Babylonia that Jerusalem was destroyed? Through the double blow the national life of the Jews was threatened with utter extinction. Both empires, therefore, appeared to the Jews as incarnations of all that was evil and cruel and sinful.

Assyria was cruel toward her foes and, if Babylonia has a gentler record, it is because she never so greatly developed military prowess as did her northern cousin. Cruelty to enemies is indeed the darkest blot on the escutcheon of all nations, ancient or modern. The Hebrews are no exception, and one need only read the pages of their own chronicles to match therein some of the cruelties so vividly depicted by the Assyrians on their monuments. To judge fairly of the ethics of any people, we must take them at their best. War for conquest, while it may lead to heroic exploits, unfolds the worst passions of men. This has always been the case and always will be. The conqueror is always haughty and generally merciless, the conquered are always embittered and filled with hatred towards those who have humiliated them. Tested by their attitude towards rivals and foes, what modern nation can stand the judgment of an Isaiah or a Jeremiah? The culture that developed in the Euphrates Valley is full of defects, its ethics one deficient, the religion full of superstition. Assyria exhausted her vitality by ceaseless warring; Babylonia fell into decay through internal dissensions and through intrigues against her rival. The pages of the annals of both nations are full of abhorrent stains, but maugre all drawbacks, the tendency of culture, religion, and ethics was toward higher ideals; the movement was in the right direction.