Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria

by Morris Jastrow | 1911 | 121,372 words

More than ten years after publishing his book on Babylonian and Assyrian religion, Morris Jastrow was invited to give a series of lectures. These lectures on the religious beliefs and practices in Babylonia and Assyria included: - Culture and Religion - The Pantheon - Divination - Astrology - The Temples and the Cults - Ethics and Life After Death...

Lecture IV - Astrology

I

AN attempt to read the future in the stars is hardly to be found in the earliest stirrings of civilisation. The ability to grasp even the thought of it transcends the mental reach of man in the lower stages of civilisation. Astrology, does not, therefore, emerge until we come to the higher phases of culture. It appears at the start rather as an expression of the science of the day, as attained by the select few, than as an outcome of the beliefs held by the many. In this respect, astrology presents a contrast to liver divination, which, as we have seen, is based on the beliefs that are distinctly primitive and popular in character, though it was finally developed into an accurate system, through the agency of the priests of Babylonia and Assyria.

The fundamental factor in astrology is the identification of the heavenly bodies with the chief gods of the pantheon. The personification of the sun and moon as gods—using the term god in its widest sense as the belief in a superior Power, supposed to exercise a direct influence upon man—comes within the scope of popular beliefs; but the further step involved in astrology, to wit, the identification of the planets and fixed stars with the gods themselves, is beyond and above this scope, though this identification represents a logical extension of the thought which led to the personification of sun and moon as gods. It is precisely this extension of the logical process that stamps astrology from its rise as a reflection of the science, or, possibly, the pseudo-science of the day. A moment’s thought will make this clear. The influence of sun and moon as active powers, affecting the fortunes and welfare of mankind, is manifest even to people living in a primitive state.

The sun is an all-important element, not only as furnishing light and heat, but because of its co-operation in producing fertility of the soil; and, naturally, when the agricultural stage is reached the sun becomes indispensable to the life of the individual as well as to the community.

The moon, though its utility is less obvious, is serviceable as a guide at night; its regular phases constitute an important factor in the measurement of the seasons. While the thought, however, that the stars, too, are gods might occur to man in his earlier stages, it would not be likely to make any deep impression, because of the absence of any direct link between his own existence and theirs.

Winds and storms would be personified because they directly affect man’s well-being. This includes a personification of thunder and lightning. But even assuming that the stars too had been personified, the symbolism involved in making them the equals of gods, and in identifying them with the powers whose real functions belong to the earth, could only have arisen in connection with a more profound theory regarding the relation of the starry universe to occurrences on this globe.

The theory upon which astrology rests—for it did not originate in mere fancy or caprice—is the assumption of a co-ordination between occurrences on earth and phenomena observed in the heavens. One needs only to state this theory in order to recognise its abstract character—relatively abstract, of course. It smacks of the school, and is just the kind of theory that would emanate from minds intent on finding explanations of the mysteries of the universe, more satisfactory than those deduced from the crude animistic conceptions inherent in primitive culture. To be sure, even on the assumption of a co-ordinate relation between heaven and earth, there is still room for a considerable measure of arbitrary speculation, but the theory itself marks an important advance toward the recognition of law and order in the universe. The gods, whose manifestations are to be seen in the heavens, still act according to their own fancy, yet they at least act in concert. Each separate deity is no longer an unrestrained law unto himself; and, moreover, what the gods decide is certain to happen. Astrology makes no attempt to turn the gods away from their purpose, but merely to determine a little in advance what they propose, so as to be prepared for coming events.

Through the theory upon which astrology rested an explanation was found for the constant changes of the heavenly bodies. These changes, involving not only alterations in the appearance and position of the moon but also in the position of certain stars, were interpreted as representing the activity of the gods in preparing the events to take place on earth. Changes in the heavens, therefore, portended changes on earth. The Biblical expression “hosts of heaven” for the starry universe admirably reflects the conception held by the Babylonian astrologers. Moon, planets, and stars constituted an army in constant activity, executing military manoeuvres which were the result of deliberation and which had in view a fixed purpose. It was the function of the priest—the bdru, or “inspector,” as the astrologer as well as the “inspector” of the liver[1] was called — to discover this purpose. In order to do so, a system of interpretation was evolved, less logical and less elaborate than the system of hepatoscopy, which was analysed in the preceding chapter, but nevertheless meriting attention both as an example of the pathetic yearning of men to peer into the minds of the gods, and of the influence that Babylonian-Assyrian astrology exerted throughout the ancient world. This astrology, adopted by the Greeks, and welded to Greek modes of thought and Greek views of life, was handed on from generation to generation through the Middle Ages down to the very threshold of modern science. Before, however, discussing this theory and its interpretation, we must consider the heavenly bodies specially recognised by Babylonian and Assyrian astrologers. -

II

Inasmuch as astrology deals primarily, as a system of divination, with the phenomena observed only at night, the foremost place is naturally occupied by the great orb of night, the moon, which, when a personified power, was designated as En-Zu, “the lord of wisdom,” and had the general name Sin.1 While the designation of Sin, as the “lord of wisdom,” is perhaps older than the mature astrological system, the name well illustrates the views associated with the moon-god in astrology. The “wisdom” meant is, primarily, that which he, the moon-god, derives from his preeminent position among the forces or hosts of heaven.

11 am inclined to see in En-Zu or Zu-En an artificial combination based on a “punning” etymology of Sin, and intended to set forth a chief attribute of the moon-god. See above, p. 112, note 2.

He is there the wisest of the gods, the chief councillor in directing the affairs of mankind and of the universe. The title, so frequently assigned to him, of the “father” of the gods, to be found in “Sumerian” compositions of an early period,[2] is likewise particularly applicable to a system of astral theology; it is as the chief luminary of the night that he becomes the “father” of the planets and stars, particularly when we bear in mind that in ancient as well as in modem Oriental speech, “father”is a synonym of chief and leader.

In astrological texts, Sin always takes precedence over Shamash, the sun-god, and as a direct consequence of the influence exerted by astrology upon the development of the Babylonian-Assyrian religion, Sin is placed before Shamash in the enumeration of the members of the pantheon in all kinds of texts, after a certain period.[3] In the case of the moon, the chief phenomena to which attention was directed were the appearance of the new-moon or conjunction with the sun; the period of full-moon or opposition to the sun; the disappearance of the moon at the end of the month; halos—large and small—appearing around the moon; unusual phenomena, such as obscurations of the moon’s surface due to atmospheric causes, and, lastly, eclipses.

Astrology in Babylonia is many centuries older than the regulation of the calendar by adjusting the movements of the moon to the annual revolution of the sun. Indeed, it is not until after the conquest of the Euphrates Valley by the Persians that we come upon calculations regarding the movements of the new-moon, while a lunar cycle of nineteen years was not introduced until about the third century B.C. Prior, therefore, to this advance in genuine astronomical knowledge, actual observation was the sole method employed to determine each month the time of the appearance of the new-moon, whether it would be on the evening of the 29th or on the evening of the 30th day. In case the heavens were obscured by clouds on the night when the new-moon was expected to appear, it was considered a bad omen; and an astrologer was obliged to wait for a clear night, before it could be determined by the position and appearance of the moon, whether or not the expected day had been the first day of the month.

This uncertainty in regard to the new-moon involved an even greater uncertainty each month in regard to the time of full-moon. The astrological texts offer a margin of no less than five days, as a possible time of full-moon, from a premature appearance on the 12th and 13th day to a belated appearance on the 15th or 16th day, with the 14th regarded as the normal period. Both the too early and the too late appearance were regarded as unfavourable omens, because of the element of abnormality, but the exact nature of the unfavourable omen varied with the months of the year. It prognosticated bad crops if it occurred in one month; pestilence, if in another; internal disturbances of the country, if in a third. Thus, also, a premature disappearance of the moon at the end of the month, or an absence of the moon for more than the normal three days, was viewed with dismay, and, indeed, even its disappearance at the normal time occasioned anxiety—a survival of earlier beliefs which regarded this disappearance as the capture of the moon by hostile powers in the heavens.[4] This day of disappearance was called a “day of sorrow.”[5] Solemn expiatory rites were prescribed, primarily, for the ruler, who had to exercise special precautions not to provoke the gods to anger during those anxious days. The Arabs of our days still hail the appearance of the new moon with exclamations of joy and clapping of hands, calling it by a term, hilâl,[6] which, like its derivative “Hallelujah,” emphasises in its very sound the relief felt at the release of the moon from captivity.

Greater terror was proportionately aroused by an eclipse or by any unexpected obscuration of the moon’s surface. It does not appear that the Babylonians and Assyrians, even in the latest period, suspected the real cause of an eclipse of the moon or of the sun; though it is not impossible that at a late date they noted the regular recurrences of eclipses. In the astrological texts the term for eclipse— atalû , signifying “shadow”—is used for any kind of obscuration of the moon or the sun, including the greyish or yellowish appearance due to purely atmospheric effects. The astrologers, therefore, speak of an “eclipse” occurring on any day of the month,[7] without realising that an eclipse of the moon can take place only in the middle of the month, and a solar eclipse at the end of the month. No better illustration can be desired of their deficiency in any genuine astronomical knowledge, until, at a comparatively late period, the spell of astrological divination was broken by the recognition of the regularity of the movements of the heavenly bodies.

In the case of the sun, obscurations and eclipses constitute the most striking features. As in the case of the monthly disappearance of the moon, popular fancy imagined an eclipse of the moon or sun to be due to a temporary discomfiture of these two great luminaries in a conflict with the hosts of heaven. Among a primitive people the terror aroused by an eclipse thus became the origin for the general unfavourable character of the omens associated with such disturbances in the heavens. To this extent, therefore, there is a connecting link between popular beliefs and the developed system of astral theology, but we pass beyond popular beliefs when we come to other phenomena connected with the sun, such as mock-suns appearing around the sun, which are due to atmospheric conditions, or horizontal rays occasionally seen extending from either side or from both sides of the sun. Such phenomena appear to have excited attention among a primitive people in no greater degree than the halos around the moon, which the Baby Ionian-Assyrian astrologers designated as courts or stalls according to their size. These phenomena, as well as the changes in the position of the wandering stars or planets, fall within the observation of a restricted circle of more scientific observers, who scanned the heavens for signs of the activity of the gods to whom seats had been there assigned.

III

In regard to the planets, there are reasons for believing that Jupiter and Venus were the first to be clearly differentiated, Jupiter by virtue of its brilliant light, Venus through the striking fact that it appeared as an evening star during one part of the year, and as morning star during another. In the astrological system Jupiter was identified with Marduk, who, we have seen, became the chief god of the pantheon after the Hammurapi period; and Venus with the chief goddess Ishtar. As was pointed out in a previous lecture,[8] Marduk appears to have been, originally, a solar deity. This identification with Jupiter is, therefore, artificial and entirely arbitrary; and shows that in this combination of planets with the chief gods and goddesses of the pantheon, the original character of the latter was entirely set aside. The same is true in the identification of Venus with Ishtar, for Ishtar is distinctly an earth goddess, the personification of mother-earth, viewed as the source of vegetation and of fertility in general. The twofold aspect of Venus as evening star and morning star was no doubt a factor in suggesting the analogy with the goddess Ishtar, who likewise presents two aspects—one during the season of vegetation, and quite another during the rainy and wintry season, when she appears to have been withdrawn from the scene of her labours, or, as the popular fancy supposed, when she was imprisoned in the bowels of the earth by her hostile sister—the goddess of the lower regions.

The identification of Jupiter with Marduk furnishes us with a valuable clue for determining the period when the system, to be noted in the astrological texts, was perfected. As a direct consequence of the high position assumed by Babylon after the union of the Euphratean states under Hammurapi, the patron deity of that city is advanced to the position of head of the pantheon. Had the astrological system been devised at an earlier period, Enlil, the chief god of Nippur and the head of the earlier pantheon, would have been associated with Jupiter, and Ninlil (or, possibly, Nana of Uruk) with Venus, while, had the priests of Eridu been the first to make each planet a personification of one of the great gods, they would have assigned the most important place among the planets to Ea, as the chief deity of Eridu. In fact, we find few allusions to astrology in inscriptions before the first dynasty of Babylon, though it is quite certain that the beginnings of Babylonian astrology belong to the days of Sargon. Still, it is significant that the only omens about Sargon and his son Naram-Sin that have come down to us are explanations of signs derived from the inspection of the liver of sacrificial animals.[9]

In like manner, other allusions to the early heroes and rulers of Babylonia—to Urumush, Ibe-Sin, and Gilgamesh—occur chiefly in the liver divination texts,[10] and only rarely in collections of astrological omens.[11] We may, therefore, trace the perfected system of astrology (as revealed in what texts we have) back to ca . 2000 B.C. As to Jupiter, attention was paid to the time of its heliacal rise and disappearance, and to its lustre—whether, to use the astrological terms, it was “strong” or “weak.” Certain months were assigned to certain countries:—the first, fifth, and ninth to Akkad; the second, sixth, and tenth to Elam (to the east); the third, seventh, and eleventh to Amurru (to the west); the fourth, eighth, and twelfth to Subartu or Guti (to the north); and, according to the month when Jupiter appeared or disappeared, the omen was applied to the corresponding country. The “strong” appearance of the planet was a favourable omen; its “weak” appearance, by association of ideas, pointed to loss of power; but whether the loss was for the king and his land or his forces, or for the enemy’s land would depend on such factors as the month, or even the day of the month when the phenomenon was observed.

For Venus we have, at the outset, the distinction between her appearance as an evening star and as a morning star. Elaborate tables were prepared, based on observation, or drawn up after a conventional pattern, noting the time of her heliacal rise as morning star, the duration of visibility, the time of her setting, the length of time during which she remained “hidden in the heavens,” as runs the astrological phrase, and the day and month of her reappearance as evening star. To each entry the interpretation was attached, and this varied according to the length of time that Venus was visible, and the character of the month wherein she reappeared. These long lists, worked out in great detail, again illustrate the purely empirical character of such astronomical knowledge as the Babylonians and Assyrians possessed, down at least to the sixth century B.C. For instance, the period, according to scientific investigation, between the heliacal setting of Venus and her heliacal rise is seventy-two days; but in the Babylonian-Assyrian astrological texts, thejperiod varies from on e jnpnth to five m flnfchs=-too short on the one hand, and too long on the other. In order to account for such discrepancies, we must, perforce, assume that the observations were defective —for which there is indeed abundant evidence—and that the lists, being composite productions of various periods, embody the errors of earlier ages incorporated in the more accurate records of later periods, though even these too were based upon merely empirical knowledge.

But whatever be the explanation, the ignorance of the Babylonian and Assyrian astrologers is patent; and the infantile fancies which frequently crop out in these astrological texts keep pace with the ignorance. Thus, the peculiar scintillations of Venus, when particularly bright, gi ve to her outline the appearance of rays. When these rays were observed, Venus was said to “have a beard,”[12] and when the sparkling edges faded in lustre, Venus was said to have “removed her beard.” Venus with a “beard” was in general favourable, while Venus without a beard was in general unfavourable, though here, too, the interpretation varied according to the month in which the “beard” was put on, or taken off. When the rays appeared over Venus, she was recorded as “having a crown,” and a distinction was made between a “sun” crown and a smaller one, a “moon” crown,or crescent,—all of which illustrates the naivete of their astronomical explanations even while revealing their anxiously close observations.

The remaining three planets—Saturn, Mercury, and Mars—were at first combined in the designation Lu-Bat, which became the general term for “planet.” The term[13] conveys the idea that the movements of these planets were observed for the purpose of securing omens, but, originally, either Saturn, or Mercury, or Mars was meant when the movement or the position of a Lu-Bat was referred to. This circumstance carries with it the plausible conclusion that, before the three planets were more sharply differentiated from one another, the interpretation given to phenomena connected with any one of them was the same as that given to the others. The reason, no doubt, for thus grouping the three into one class was the difficulty involved in observing their separate courses. They bore no specially striking features, such as Jupiter or Venus possessed, and this was, also, no doubt, a cause which led to their being at first put upon the same plane. Of the three, Saturn appears to have been the first to be more definitely differentiated from the others. At all events, in the completed system Saturn was placed above Mercury and Mars.

It received the designation of the “steady’' Lu-Bat[14] because of the slowness and regularity of its movements. Requiring about twenty-nine and a half years for the revolution in its orbit, Saturn is visible for a longer continuous period than Mercury or Mars. Possibly by an association of ideas that might occur to them but not to us, Saturn was also looked upon as a kind of second sun — a smaller Shamash by th e side of the great Shamash of the day.[15] Was there, perchance, a "learned theory” among the astrologers that the illumination of the night was due to this inferior sun of the night, which, because of its prolonged presence, seemed more likely to be the cause thereof than the moon, which nightly changed its phase, and even totally disappeared for a few days each month?[16] It would verily seem so; but, at all events, the fact that Saturn was also called the “sun” is vouched for, both by explanatory notes attached to astrological collections, and by notices in classical writers to that effect. As one of these writers[17] has it, “Saturn is the star of the sun” —its satellite, so to speak, and alter ego.

This association of Saturn with the sun may have been a reason for identifying Saturn with a solar deity, Ninib, who, it will be recalled, was the sun-god of Nippur, and only second in rank to Enlil after this “intruder” displaced Ninib[18] from the actual leadership of the pantheon which he once occupied. Ninib, accordingly, is well fitted to be the associate and “lieutenant” of Shamash, the paramount sun-god from a certain period onward.

Next in importance to Saturn comes Mars, which, in contrast to Saturn exerting, on the whole, a most beneficent influence, was the unlucky planet. This unlucky and downright hostile character of Mars is indicated by his many names: such as the “dark” Lu-Bat; “pestilence”; the “hostile” one; the “rebellious” one; and the like. He was appropriately identified with Nergal, the sun-god of Cuthah, who, in the process of differentiation among the chief solar deities of Babylonia, became the sun of midsummer, bringing pestilence, suffering, and death in its wake;[19] in contrast with Ninib who was viewed more particularly as the sun-god of the spring, restoring life and bringing joy and gladness. In the systematised pantheon, it will be recalled, Nergal was regarded as the grim god of war, and also as the deity presiding over the nether world—the Pluto of Babylonia, who, with his consort Ereshkigal, keeps the dead imprisoned in his gloomy kingdom. The association of ideas between Nergal, the lord of the “dark” region, and the dark-red colour of Mars may be regarded as an element of the identification of Mars with Nergal, just as the ideas associated with the colour red—suggesting blood and fire—furnished the further reason for connecting ill-boding omens with the appearance of Mars, and with his position relative to other planets and stars. As an unlucky planet, the “stronger” Mars appeared to be in the heavens, the more baneful his influence. Hence the brilliant sheen of the planet —in contrast to what we have seen to have been the case with Jupiter-Marduk—augured coming misfortune, while the “faint” lustre, indicating the weakness of the planet, was regarded as a favourable sign.

The least important of the planets in Babylonian-Assyrian astrology is Mercury. Because of its nearness to the sun, it is less conspicuous than the others, and the most difficult to observe, and was, therefore, termed the “faint” planet.[20] It is also visible for the shortest period. It can be seen with the unaided eye for only a little while, either shortly after sunset or before sunrise, and only during a part of the year. In northern climes even these restricted glimpses are not always accorded, and Copernicus is said to have regretted on his death-bed that he had never actually seen Mercury. As the least significant of the planets, there was not the same reason to distinguish Mercury by a specific designation, and hence, instead of being always referred to as the “faint” planet, it is just as often termed simply Lu-Bat, not in the sense of being the one planet of all others as was at one time supposed, but simply as a planet having no special distinction. Mercury as Lu-Bat is, as it were, the relict of the planets, the one left over of the group, the Cinderella among the planets, relegated to an inferior position of relative unimportance and neglect. Because of its smaller size and of its associations, Mercury is identified with the god Nebo, who in the systematised pantheon, it will be recalled, was the son of Marduk, and the scribe in the assembly of the gods, the recorder of the decrees of the divine court, and also the court messenger.

This relationship of son to father wherein Nebo stands to Marduk—Jupiter—is well brought out in an Assyrian astrological report where Mercury is calle “the star of th e crown prince” wit h an a llusion to the frequent designation of Jupiter as the “king” star.[21] Frequently also Mercury is described as the “star of Marduk,”[22] the satellite and “lieutenant” of Jupiter, much as Saturn is in the same way styled “the star of Shamash.” This varied character of the planet had, however, curious consequences. In Greek astrology, which, as will be presently shown, is largely dependent upon the Babylonian-Assyrian system, Mercury possesses qualities belonging to all the other planets. It is both male and female, and the only one of the planets of whom this is said. The association of ideas connected with Nebo, the god of wisdom, in a very specific sense, and of the art of writing, led to Mercury’s being regarded also as the planet of intelligence. The designation of Mercury as Lu-Bat indicated that Mercury summed up the essence of the powers attributed to the planets in general, so that even in the latter-day astrology, which survived the revolution of thought brought about by the natural sciences, Mercury is still associated with the soul— the seat of all vitality.[23] In Babylonian-Assyrian astrology Mercury is a planet of a favourable nature. Its appearance is in almost all cases a good omen. The interpretations fluctuate with the months in which the planet is seen, but frequently refer to abundant rains and good crops.

The scope of Babylonian-Assyrian astrology was still further extended by the inclusion of the more conspicuous stars and constellations, such as the Pleiades, Orion, Sirius, Aldebaran, the Great Bear, Regulus, Procyon, Castor and Pollux, Hydra, and others. The omens deduced, however, from constellations and single stars were dependent, primarily, upon the position of these constellations and stars relative to the planets. According as the planets approached or moved away from them, the omen was regarded as favourable or unfavourable, and the decision was again dependent upon their own associations. Thus, if Venus passed beyond Procyon, it pointed to the carrying away of the produce of the land; if she approached Orion it prognosticated diminished crops, —a meagre yield from palms and olives.[24]

With a realisation of the fact that the sun and planets move in well-defined orbits, the need of distinguishing the exact position occupied at any given moment by any of those bodies naturally became pressing. The ecliptic, known as the “pathway of the sun,” was divided into three sections, each designated for one of the deities of that theoretically accepted triad which summed up the powers and subdivisions of the universe.[25] These sections were known as the paths of Anu, Enlil, and Ea respectively. Each of these sections was assigned to a country, the Anu section to Elam, the Enlil section to Akkad, and the Ea section to Amurru. Elam lying to the east of the Euphrates Valley, and Amurru lying to the west, Akkad was in the middle between the two. According as a planet in its course stood in one division or an other, the omen was supposed to have special reference to the land in question. Thus the planet Venus, when rising in the division of Ea, portended that Amurru would have superabundance, if in the division of Anu that Elam would be prosperous, and if in the division of Enlil that Akkad would be benefited. In like manner, if Venus reached her culmination in the division of Anu, Elam would enjoy the grace of the gods, if in the division of Enlil, then Akkad, and if in the division of Ea, Amurru would be so favoured.[26]

This threefold division of the ecliptic does not appear, however, to have been an indication sufficiently precise of the position of the planet; accordingly, the stars near the ecliptic were combined into groups, and designations more or less fanciful were given to them. In this way, twelve such groups were gradually distinguished, corresponding to our constellations of the zodiac, though, it should be added, there are no indications that the Babylonians or the Assyrians divided the ecliptic into twelve equal divisions of 30° each. Retaining the division of the ecliptic into three equal sections, they distributed constellations among these sections as a further means of specifying the position of a planet at any moment, and also as an enlargement of the field of astrological divination. From symbols on the so-called boundary stones, it appears that up to ca. 1000 B.C., only four or five constellations in the zodiac were distinguished, and we must descend to the Persian period before we find the full number twelve marked out along the ecliptic. Undoubtedly, the enlargement of four or five to twelve—for which there seems no special reason, unless to bring about a correspondence with the twelve months of the year—represents the result of continued observation, but its main purpose was to enlarge still further the field of divination.

Astrology, like every system of divination, thrives in proportion to an increase in its signs. The more complicated the system, the greater its hold upon the masses, who had no means of checking ther element of capriciousness in the interpretations by bârû priests. The twelve constellations, thus gradually traced along the ecliptic by the priests of Babylonia and Assyria, correspond, with some exceptions, to the twelve signs of the zodiac still employed in moderm astronomy. Thus we have ram, twins, lion, crab, scorpion, archer, and fishes in Babylonian-Assyrian astrology. In place of the virgin we have a constellation designated as “plant-growth,” instead of the bull, a spear; the reamainder are still in doubt.[27] The dependence of modern astronomical nomenclature on Babylonian astrology—through the mediation of the Grecian—is thus recognised beyond reasonable doubt,[28] but the significant feature of this dependence lies in the circumstance that what, under the moulding of the Greek scientific spirit, became astronomical in character was adopted by the Greeks as a purely fanciful combination of stars into groups, introduced as a means of fixing more accurately the stations of the sun and planets in their course along the ecliptic, and for the sole purpose of enlarging the field of divinatory lore.

IV

It now behooves us to turn to a description of the system devised by the bdru priests in their endeavour to read in the movements of the heavenly bodies and in the general phenomena of the heavens, the purpose and designs of the gods.

Although not belonging to astrology proper, yet, from the Babylonian point of view, storms, winds, rains, clouds, thunder, and lightning constitute an integral part of divination based upon the phenomena of the heavens; and we have seen that this phase of divination,[29] like divination from the movements and position of the sun and moon, represents an outcome of the popular beliefs that naturally connected these phenomena with beings that had their seats on high. We cannot, in fact, separate the interpretations of winds, clouds, rain, hail, thunder, lightning, and even earthquakes from astrology proper, for, in the astrological texts, Adad, who, as the god of storms, presides over all the violent manifestations in the heavens that show their effect on earth, is accorded a place by the side of Sin, Shamash, and the gods identified with the five planets, Marduk, Ishtar, Ninib, Nebo, and Nergal. These eight deities in fact constitute the chief gods of the perfected pantheon, to which the ancient triad Anu, Enlil, and Ea should be added, together with Ashur in Assyria[30] as the additional member of a conventionalised group of twelve deities.

Naturally, the phenomena ascribed to Adad furnished a particularly wide scope for the astrologer. The character and ever-changing shapes of clouds were observed, whether massed together or floating in thin fleecy strips. Their colour was noted, whether dark, yellow, green, or white. The number of thunderclaps, the place in the heavens whence the sound proceeded, the month or day or special circumstances when heard, were all carefully noted, as was also the quarter whence the lightning came, and the direction it took, the course of winds and rain, and so on, without end.

In studying the system devised for the interpretation of omens, we may take as a point of departure the subdivision dealing with the activity of the god Adad. As in liver divination, the general principles were deduced from the observation of events actually following upon certain noteworthy phenomena in the heavens. If, for example, a battle was fought during a thunderstorm and ended in the discomfiture of the enemy, the precise conditions under which the battle took place, the day of the month, the direction of the wind, and the number of thunderclaps were noted. The conclusion was then drawn that, given a repetition of the circumstances, the same result or at least some favourable outcome would follow. This same principle was applied to the position of the sun, moon, or any of the planets at any given moment. As a necessary outcome of the theory that whatever occurred in the heavens represented the activity and co-operation of the gods in events on earth, the post hoc was equated with the propter hoc in the case of all important or striking occurrences, directly affecting the general welfare. The conclusion was inevitable that the phenomenon itself portended the events. Hence, the scrupulously careful observation of heavenly phenomena yielded an infallible guide for the most confident prediction —always provided that the records confirmed an occurrence in the past when preceded by similar phenomena, or provided that in any other way a correct reading of the sign could be given. How was this possible when records or tradition were lacking? The answer is the same that was suggested in regard to the system of liver divination,—it was by certain more or less logical deductions, and also by more or less fanciful association of ideas.[31]

V

It does not appear that the Babylonians and Assyrians advanced so far as the mapping out of the heavens to correspond with the distribution of lands, mountains, rivers, and seas on earth; though this would have been a perfectly logical extension of the theory of a preordained correspondence between heaven and earth. It was actually carried out, however, by the later Greek astrologers.[32] We have already seen that the divisions of the ecliptic were associated with certain countries; certain divisions of the moon, the left and right sides, the upper and lower portions, were parcelled out in the same way.[33] The world was divided for purposes of astrology into four chief lands with which the Babylonians had come into contact. Elam was the general designation of the east, Amurru, or the land of the Amorites, meant the west, Akkad, or Babylonia, stood for the south, and Subartu, alternating with Guti, for the north. The omission of the later name, Ashur, for Assyria is important; it points to the development of the astrological system prior to the rise of the Assyrian empire, which, in fact, is not prominent until sometime after the period of Hammurapi. Subartu stands in the conventional enumeration for the later Assyria, and the astrologers of that country are careful enough expressly to note this fact.[34] These four divisions, Elam, Amurru, Akkad, and Subartu (with Guti as an alternative[35]) constituted the “four regions” of the earth.

Rulers, like Naram-Sin, who claimed control of these sections, therefore gave themselves the title of “King of the Four Regions,”—with the implication that their empire was of universal sway. It was not necessary to map out the heavens to correspond to these four divisions. Indeed, a larger margin was allowed to the astrologers by not doing so; the divisions could then be applied to any of the five planets, to the constellations, and single stars, as well as to the sun and moon and to the divisions of the ecliptic. Jupiter, quite independently of his position in the heavens at any given time, was regarded as the planet of Akkad or Babylonia, while Mars, as the hostile and unlucky planet, was assigned to the two unfriendly lands, Amurru and Elam. Thus, too, the constellations and prominent single stars were apportioned among the same four countries. We are fortunate enough to possess lists wherein the planets, constellations, and stars, arranged in groups of twelve to correspond to the twelve months of the year, are thus divided among Elam, Akkad, Amurru, and Subartu.[36] We have already seen that the months were in the same way distributed among these four countries, and the system was even extended to days, so that each day of the month was referred to one country or another.[37] It was thus possible to connect almost every phenomenon in the heavens with some country.

This was more particularly important in the case of unfavourable omens, like eclipses, or obscurations of the sun or moon from atmospheric causes, where the application of the interpretation would thus vary according to the month and the day on which the phenomenon was observed. The scope thus given to the prognostications of the bard priests was extended still further by connecting the months with the gods as well as with countries, and, according to the character and nature of each deity, an appropriate interpretation was proposed for the many cases in which no record existed of any event of special significance following upon some sign in the heavens. Thus, the first month was assigned to Anu and Enlil, the second to Ea, the third to Sin, the fourth to Ninib, the fifth to Ningishzida (also a solar deity and a god of vegetation), the sixth to Ishtar, the seventh to Shamash, the eighth to Marduk, the ninth to Nergal, the tenth to the messenger of Anu and Ishtar —presumably Nebo,—the eleventh to Adad, the twelfth to Sibitti, the intercalated, so-called second Adar to Ashur, the head of the Assyrian pantheon.[38]

The factors involved in such associations are various. To discuss them in detail would take us too far afield; it is sufficient to call attention to the “mythological” considerations involved. The sixth month—marking the division of the year into two halves—is connected with the goddess Ishtar, who spends half of the year on earth and half in the nether world. Climatic conditions underlie the association of the eleventh month—the height of the wintry and stormy season—with the god of storms and rains, Adad. Similar associations are to be found in the famous Babylonian epic known as the adventures of Gilgamesh, which was recounted on twelve tablets, each tablet being made to correspond to a certain month of the year. The sixth tablet narrates the descent of Ishtar to the lower world—symbolising the end of the summer season of growth and of vegetation; the story of the great Deluge that swept away mankind is recounted in the eleventh tablet—corresponding, therefore, to the month associated with Adad.

Besides the division of the four sides of the moon—right and left, upper and lower—among the four regions of the world, as above pointed out, we find a special distribution when the moon was crescent, the right horn being assigned to Amurru or the west land and the left horn to Elam or the east. In this case, orientation, which in Babylonia was from the south, is clearly the controlling factor. Facing the south, the west is to the right and the east to the left, whereas when the full moon is divided among the four countries, the assigning of Akkad to the right side and of Elam to the left is due to the natural association of ideas between right and lucky, on the one hand, and left and unlucky on the other, which, we have seen, played so important a part in liver divination.

Facing Akkad, as the land of the south, the lower portion of the moon would again be the left and therefore unlucky side, and the upper portion the right or lucky side, which leads to the former being associated with the land of the enemy, Amurru, and the latter with Assyria—replaced, whenever it suited the purpose of the astrologers, by Subartu. In this and in divers other ways the association of ideas becomes perhaps the most important factor in the development of the system of interpretation, by the side, or in default, of the direct observation of events following upon certain phenomena in the heavens. This latter phase must, never, of course, be lost sight of, and especially when extraordinary phenomena appeared in the skies, such as a thunderclap out of a clear sky, rain during the dry season (in the 4th, 5th, and 6th months), an apparently belated new-moon or full-moon, and, above all, eclipses of the sun or moon, or obscurations of either of these heavenly lamps. All such occurrences would make a deep impression, and special care would be taken to note every event that followed, in the belief that all the signs here instanced being unfavourable, whatever misfortune or unlucky occurrence happened, it was a direct consequence of the unfavourable sign in the heavens, or was at all events prognosticated by the sign.

VI

The events would naturally be of general public import. These may be chiefly enumerated as the result of a military expedition, condition of the crops, pestilence, invasion of the enemy, disturbances within the country, a revolt, an uprising in the royal household, or any untoward event at court, such as the sickness or death of the monarch, or of a member of his house—always indicative of the anger of the gods, —a miscarriage of the queen, a mishap to the crown-prince, and the like.

Thus as in the case of hepatoscopy, the point of view was always directed to the general welfare. Private affairs hardly entered into consideration; not for such were the stars to be read. The bārū priests did not painfully search the heavens to find out under what special conjunction of planets a humble subject was born, or try to determine the fate in store for him. This aspect of astrology is conspicuous by its absence. And when astronomy devoted itself to the service of the king or to a member of his household—for the interpretations in the astrological texts often bear upon events in the palace or at the court,— it is due[39] to the peculiar position held by the king throughout antiquity. He was regarded either as the direct representative of the deity on earth, or as standing in a peculiarly close relationship to the gods; wherefore should he act in any way to provoke the gods to anger, his punishment would affect the entire population.

On the other hand, the favour of the gods toward the king ensures victory in arms, the repulse of an enemy, abundant crops, and the blessings of health and happiness. In return, the kings had to exercise special precautions in all their acts— official and otherwise. A misstep, a failure to observe certain rites, a neglect of any prescribed ceremonial, or a distinctly ethical misdemeanour, an act of injustice or cruelty, might be fraught with the most dire results. If a catastrophe or misfortune affecting the general welfare occurred, it was taken as a sign of divine displeasure. In such cases, expiatory rites were prescribed for the king, and often for the members of his household also, for fear that the anger had been evoked by some misdeed of theirs, albeit an unintentional one.

This trait of solidarity of king and people and gods, as opposed to individualism, marks the Babylonian-Assyrian religion in all its phases. It is by no accident that the hymns and prayers and penitential appeals and ritualistic directions are almost universally engrossed with the relation of the rulers to the gods. The prayers to Enlil, Marduk, Sin, Shamash, Nebo, Ninib, or Ishtar are generally royal appeals; the hymns voice the aspirations of the kings, while the penitents, whose humiliation before the divine throne is portrayed in such effective manner, in the penitential outpourings,[40] are in almost all instances the rulers themselves. To be sure, this condition is in a measure due to the official character of the religious material in the library of Ashurbanapal, and yet this material taken directly from the archives of the temples fairly reflects the general features of the religion. Even in the incantations, the formulas and observances prescribed for exorcising mischievous demons (the causes of all the ills of existence, and of the unpleasant accidents of every day life), we receive the impression that the collections were largely formed to relieve the kings of their troubles; though, no doubt, in this branch of the religious literature, the needs of the individual received a more considerable share of attention. Thus also, signs that directly affected the individual, such as dreams, a serpent in one’s path, peculiar actions of dogs in a man’s house, birth of monstrosities among domestic animals[41]—all illustrate the “lay” features of the cult, but with these exceptions, the cult of Babylonia and Assyria as a whole, partook of a character official rather than individual.

What is thus true of other fields, is true of astrology. An explanation is thus found for the fundamental fact that the reading of stars by the Babylonians and Assyrians had no concern with the individual. What to us would seem to be the essence of astrology,— the determination of the conditions under which the individual was born, and the prediction from these conditions of the traits that would be his, and of the fate in store for him,—is not in Babylonian-Assyrian astrology. This aspect represents the contribution of Greek astrologers, when they carried Babylonian astrology into their own lives. To the Greeks, and afterwards to the Romans, genethlialogy,—as the science, dealing with the conditions under which a man is born, was called,—became the alpha and omega of astrology. The reason why it was left to the Greeks to add this important modification to the borrowed product is not far to seek. In the religion as in the culture of the Greeks, the individual was more than merely an infinitesimal part of the whole.

The entire spirit of Greek civilisation was individualism, and the spirit of its institutions correspondingly democratic. The city, to be sure, was regarded as an ideal unity, but the very emphasis laid upon citizenship as a condition to participation in Greek life is an indication that the individual was not lost sight of in the welfare of the whole. The individual in Greece was also, a part of the whole, but an integral part, and one that had an existence also apart from the whole. The relation between the individual and the gods was of a personal nature. The Greek gods concern themselves with individuals; whereas among the Babylonians and Assyrians the welfare of the community and of the country as a whole was primarily the function ascribed to the gods. The latter stood aloof from the petty concerns of individuals and relegated these to the inferior Powers, to the demons and spirits, and to the sorcerers and witches in whom some evil spirit was supposed to have taken up his abode.

VII

Returning to the astrological system of the Babylonians and Assyrians, it still remains for us to indicate the final form given to this system. The notes and entries made by the priests of significant events following upon noteworthy phenomena in the heavens, grew in the course of time to large proportions. Further enlarged by the settling of certain criteria for reading the stars on the basis of a logical or arbitrary association of ideas, and by the introduction of other factors, these memoranda became an extensive series in which the signs were entered in a more or less systematic manner and the interpretations added. It did not follow that, because a certain event occurred subsequent to some phenomenon in the moon, sun, or in one of the planets or in some constellation, the same conditions would always produce the same result. As was stated above, the important feature of the interpretation given to a sign was its general character as favourable or unfavourable. The essential point was whether the sign was a good or a bad omen.

Hence, in many instances we find alternative interpretations given in the astrological collections—either good crops or recovery from disease, long reign of the king or success in war, uprising in the land or low prices in the markets,—always regarded as an ill omen,—peace, and grace of the gods or abundant rains, diminution of the land or insufficient flooding of the canals during the rainy season, invasion of locusts or disastrous floods. The number of such alternative interpretations was not limited to two. Often we find three or four and as many as six contingencies. In such cases it seems simplest to suppose that these alternatives represent interpretations taken from various sources, and combined by the priests in their collections, whereof the value and trustworthiness would be increased by embodying as far as possible the entire experience and wisdom of the past for guidance in the present.

As in the case of “liver” divination, there are indications that various collections of astrological omens were compiled in the temples of the south and north, through the steady growth of the observations and deductions of the bârû priests; there was also one extensive series covering the entire field of astrology, which became, as it were, the official Handbook and main source. From the opening words it was known as the Enuma Anu-Enlil series (i.e., “When Anu, Enlil,” etc.), and probably comprised as many as one hundred tablets, of which, however, only a portion has been recovered from the great royal library at Nineveh; the tablets and fragments of tablets already preserved represent different editions or recensions of the text. Fortunately, the beginning of the series is extant, both in the original “Sumerian,” and in a somewhat free translation into Semitic Babylonian.

It expounds a piece of cosmological tradition as follows:

When Anu, Enlil, and Ea, the great gods, in their council entrusted the great laws of heaven and earth to the shining [?] moon, they caused the new-moon crescent to be renewed [5c. every month], created the month, fixed the signs of heaven and earth so that it [i.e., the moon] might shine brilliantly in heaven [and] be bright in heaven.[42]

Anu, Enlil, and Ea, it will be recalled, represent in theory the triad of divine powers, who precede the creation of the active gods. They stand, as it were, above and behind “the great gods,” and, just as the latter entrust the smaller affairs of the world—the fate of individuals—to the lower order of Powers, to the demons and spirits, so Anu, Enlil, and Ea delegate to the great gods the general affairs of mankind as a whole. The opening lines of the series are evidently quoted from a poetical composition, setting forth the order of creation. In the Sumerian original, which belongs to a very high antiquity, the moon is significantly the first and most important of the “great gods.” A reference to the sun—which is only in the Semitic translation—is presumably a later addition. The precedence hereby accorded to the moon reveals the pre-eminent position occupied by the moon in Baby Ionian-Assyrian astrology, and the quotation from the old cosmological poem was probably chosen as a befitting introduction to the exposition of omens, derived from observations of the moon. The system of the bârû priests was thus justified by the doctrine that the ancient triad in council deputed the government of the universe primarily to the moon, through which the signs to be observed in the heavens and on earth were interpreted.

There are distinct indications, throughout the recovered portions of the series, of the existence of a very old Sumerian text, which, at a period subsequent to Hammurapi, was given a Semitic form, and, in the course of this process, modified and enlarged. Equally strong is the evidence for the composite character of the series, whereof the component parts, as has already been indicated, belong to different periods and, as it would appear, embody other astrological collections that were taken over in whole or in part to form the great official guide for the priests. In short, the series is a compilation, just as are the Pentateuch and the historical books of the Old Testament. The Gilgamesh epic as well as the incantation rituals and other specimens of Babylonian Assyrian literature reveal this same practice of compilation, which is, in fact, a characteristic trait of literary composition among the Semites at all times. The great Arabic historians of the four centuries after Mohammed are, in the same way, essentially compilers and furnish a proof of the continuance of the same literary process, notwithstanding the profound changes wrought by the two millenniums between the old Babylonian literature and the intellectual activity of Mohammedan writers.

Our fragments of the Anu-Enlil series enable us to divide it into five groups; the first deals with omens derived from the moon; the second with such as deal with phenomena of the sun; the third with those of the remaining five planets; the fourth with constellations, stars, and comets, and the fifth with the various manifestations of the activity of Adad, including storms, winds, rains, thunderbolts, and lightning. In making this division it is not claimed that the tablets of the series were actually divided in this way. The Babylonian scribes and compilers were, probably, not quite so systematic; but there is sufficient internal evidence that the phenomena connected with the moon were for convenient reference grouped together. In the same way, the phenomena of the sun and those of each of the planets were dealt with in a series of tablets that aimed to exhaust all possible contingencies in connection with the movements and position of the heavenly bodies. The period of the final redaction of the series can be only approximately determined.

Historical references in connection with the omens justify the conclusion that portions of the Sumerian original may be as old as the days of Sargon (circa 2500 B.C.), but the greater portion is certainly much later, while for the final redaction we must pass far below the period of Hammurapi. Additions to it were constantly being made, and no doubt every scribe tried to improve upon his predecessors by adding more omens with their interpretations. Even the Assyrian scribes, in copying the “Babylonian” originals, did not hesitate to make additions of this kind; in a very general way we may say, however, that about 1500 B.C., the Anu-Enlil series was already in existence as the official astrological handbook. We are also safe in fixing upon the city of Babylon and its neighbour Borsippa—the two representative centres of the Marduk and Nebo cults—as the district in which the series was compiled and first recognised as the official authority.

The proof that the Anu-Enlil series was official, and consulted by the priests of Marduk and Nebo on all occasions, and that through the influence of the Marduk cult it had become the standard authority throughout Babylonia and-Assyria, is furnished by the official reports and letters of the astrologers at the Assyrian court. These reports, of which we have several hundred, consist of two sections, one containing the description of the phenomena, the other supplying the interpretations in the form of quotations from a collection of astrological omens. We now have the source of many of these quotations from the Anu-Enlil series. In like manner, in letters of Assyrian officials to their royal masters, astrological omens are not infrequently embodied, and these, too, we can trace back to the Anu-Enlil series.[43] Moreover, the series itself is directly referred to both in the reports and in the letters, being either quoted by its title or designated simply as “the Series.” It appears, therefore, that when an inquiry was put to the astrologers as to the meaning of a particular sign in the heavens, the Anu-Enlil series was forthwith consulted, the sign in question him ted up, and copied verbatim, together with the interpretation or the alternative interpretations, and forwarded to the kings with any needful explanations.

VIII

Despite the elaborate system, however, developed by the Babylonian priests, the decline of astrology sets in toward the close of the Assyrian period. It is significant that in the inscriptions of the rulers of the neo-Babylonian dynasty,—Nabopolassar to Nabon-nedos, 625 to 539 B.C., —we find no direct references to astrological omens. The gods reveal themselves in dreams and by the liver of sacrificial animals, but there are no omens derived from phenomena in the heavens. This may be, of course, accidental, and yet, considering that this period marks the beginning of a noteworthy advance in astronomy, it would rather seem that the rise of genuine astronomical science gave the death-blow to ,the belief in the revelations of stars. The advent of the Persians, who put an end to the neo-Babylonian empire in 539 B.C., was followed, as so frequently happens with the coming of a great conqueror, by an intellectual impulse. In contrast with the Babylonian religion and cult, (so full of survivals from the animistic stage), Zoroastrianism or Mazdeism, brought into Babylonia by the Persian rulers, was rationalistic in the extreme.

Instead of a multiplicity of divine Powers, we have one great spirit presiding over the universe, the creator of everything, whose power was held to be limited only by the existence at his side of a great power of evil, Ahriman, who thwarted the efforts of Ahura-Mazda until, after the completion of certain cycles, the good spirit would finally triumph over Ahriman and reign supreme. We may be permitted to suppose also that contact with the Hebrews, who under the influence of their prophets had advanced to a monotheistic conception of the universe, was a factor in leading the choicer spirits of the Babylonians to a clearer recognition of a universal divine law. A third factor destined to work still more profound changes throughout the ancient Orient was the contact with Greek culture and Greek modes of thought. Greek philosophy rested even more firmly than Hebrew monotheism on the theory of the sway of inexorable law in nature.

Thus, Persian, Hebrew, and Greek influences acted as disintegrating factors in Babylonia and Assyria, leading to a general decline in time-honoured beliefs, and, more particularly, to a diminution of faith in the gods. Astrology, along with other superstitions, was doomed the moment it was recognised that whatsoever occurred in the heavens, even including all unusual phenomena, was the result of law—eternal and unchanging law. In place of astrology, we see, therefore, a genuine science coming to the fore, which, starting from the axiom of regularity in the universe, set out to find the laws underlying the phenomena of the heavens. In the three centuries following the Persian occupation of the land we find the Babylonian priests exchanging their former profession as diviners for that of astronomers. They engage in elaborate calculations of the movements of moon and sun. They prepare tables of the movements of the planets in their orbits, with exact calendars for extensive periods of the heliacal rise and setting of the same; they calculate the duration of their forward movement, the hour of culmination, and the beginning of the retrograde movement.

The yearly calendar is regulated with more scientific' precision; and even though the recognition of the fact that eclipses of the sim and moon were, in common with all other heavenly phenomena, subject to law did not lead in Babylonia to the discovery of a true theory of eclipses, still the blasting of the belief that eclipses were symptomatic of the anger of the gods shook the very foundations of astrology. If the signs in the heavens were due to immutable laws, then the study of these signs could no longer serve to determine what the gods were purposing to do on earth. The immediate result of this progress toward a genuine astronomical science was not to bring about an era of skepticism in regard to the existence of the gods, but only to overthrow the basis on which astrology rested. If the heavens merely revealed the workings of regular laws, brooking no exceptions and proceeding independently of what happened on earth, then the function of the astrologer ceased. The connecting link between heaven and earth was snapped through the recognition of law in the universe, over which even the gods had no control.

Astronomy versus Astrology marks the beginning of the conflict between Science and Religion in Babylonia and Assyria, which, as in all subsequent phases of that conflict elsewhere, could have only one outcome,—the triumph of Science. Astrology, we have seen, started out as an expression of the science of the day. Dethroned from that position, it became, in the literal sense of the word, a superstition, a survival of an intellectual phase that had been outgrown.

Strange to say, however, the rise of astronomy and the decline of astrology in Babylonia were coincident with the introduction of astrology into the lands swayed by Greek culture. The two movements are connected. Whereas astronomy began among the Greeks long before their contact with the East, it yet received a strong impulse, as did other sciences, through the new era inaugurated by Alexander the Great, and marked by the meeting of Orient and Occident. Several centuries, however, before the days of Alexander the Greeks had begun to cultivate the study of the heavens, not for purposes of divination but prompted by a scientific spirit as an intellectual discipline that might help them to solve the mysteries of the universe. The tradition recorded by Herodotus[44] that Thales discovered the law of eclipses rests on an uncertain foundation; but, on the other hand, it is certain that by the middle of the fourth century B.C., the Greek astronomers had made great advances in the study of heavenly movements. Nor is there any reason to question that, in return for the impulse that contact with the Orient gave to the Greek mind, the Greeks imparted their scientific view of the universe to the East.

They became the teachers of the East in astronomy as in medicine and other sciences, and the credit of having discovered the law of the precession of the equinoxes belongs to Hipparchus, the Greek astronomer, who announced this important theory about the year 130 B.C. On the other hand, and in return for improved methods of astronomical calculation, which, it may be assumed, contact with Greek science also gave to the Babylonian astronomers, the Greeks accepted from the Babylonians the names of the constellations of the ecliptic; but in the case of the planets, they substituted for the Babylonian gods the corresponding deities of their own pantheon. More than this, they actually adopted from the Babylonians the system of astrology and grafted it on their own astronomical science. We have the evidence of Vitruvius,[45] and others, to the effect that Berosus the “Chaldean” priest, a contemporary of Alexander the Great, settled in the island of Cos (the home of Hippocrates), and taught astrology to a large number of students who were attracted by the novelty of the subject. Whereas in Babylonia and Assyria we have astrology first and astronomy afterwards, in Greece we have the sequence reversed—astronomy first and astrology afterwards.

How was it possible for the Greek scientific spirit to affix a pseudo-science to a genuine one? The answer to this obvious question is near at hand. It has been already[46] pointed out that the casting of an individual horoscope was the important modification introduced by the Greeks in adopting the Babylonian astrology. By this step an entirely different aspect was given to astrology, and above all, a much more scientific appearance. It was not merely the individualist spirit of Greek civilisation that led the Greeks to make an attempt to read in the stars the fate of the individual, but the current doctrine of preordained fate, which takes so large a share in the Greek religion, and was therein an important factor. Thanks to this doctrine, the harmonious combination of Greek astronomy and Babylonian astrology was rendered possible. A connecting link between the individual and the movements in the heavens was found in an element which they shared in common. Both man and stars moved in obedience to forces from which there was no escape. An inexorable law controlling the planets corresponded to an equally inexorable fate ordained for every individual from his birth.

Man was a part of nature and subject to its laws. The thought could therefore arise that, if the conditions in the heavens were studied under which a man was born, that man’s future could be determined in accord with the beliefs associated with the position of the planets rising or visible at the time of birth or, according to other views, at the time of conception.[47] These views take us back directly to the system of astrology developed by Babylonian bar'd priests. The basis on which the modified Greek system rests is likewise the same that we have observed in Babylonia —a correspondence between heaven and earth, but with this important difference, that instead of the caprice of gods we have unalterable fate controlling the entire universe—the movements of the heavens and the life of the individual alike.

The recognition of law in the heavens, which eventually put an end to astrology in Babylonia, was the very factor that gave to the transplanted system a new hold among the Greeks. Hence the harmonious combination of astronomy and astrology which has been maintained from the days of Greek civilisation, through the Middle Ages, and down to the threshold of modern science. Wherever Greek philosophy wandered, Greek astronomy, like Greek medicine, also went, and with Greek astronomy went a modified astrological system of Babylonia. Astronomy and astrology became inseparable twin sciences. The two became blended—presenting merely two aspects of one and the same object. The study of the heavens was designated “natural astrology”; the application of the study in casting the horoscopes was called “judicial astrology.” If all the great astronomers of Europe during the Middle Ages—men like Copernicus and Galileo—were also astrologers, it was due to this harmonious combination between astronomy and astrology.

But by the side of this plausible though erroneous alliance between a science and a pseudo-science, we must not fail to observe that there existed a continued influence of the old Babylonian astrology, less honourable in its character and less agreeable to contemplate. We have already taken note of the fact that when a religious custom is transplanted to a foreign soil, its degeneration sets in.[48] This happened when the divination methods of Babylonia made their way to the West. Not only was the Babylonian astrology transferred to Greece but the barii priests went with it. During the three centuries after Alexander we frequently read in Greek and Roman authors of “Chaldeans” following the armies as diviners, and plying a profitable trade in furnishing omens on all occasions. These “Chaldeans” emerge not only as astrologers, but as diviners by the liver. Their reputation was none of the best. Greek and Latin writers rehearse the tricks with which they plied their trade,[49] until in time “Chaldean” became synonymous with “imposter.” But, on the other hand, it is also significant of the influence which Babylonian practices continued to exert three centuries before our era, that the term “Chaldean” became synonymous with diviner and more particularly with one who read the future in the stars.

It does not follow, therefore, that all diviners who are spoken of as “Chaldeans” necessarily come from Mesopotamia. They appear frequently to have been natives of Egypt, where —no doubt under influences coming from the East—divination flourished during these three centuries as it never did in the pre-Grecian period of Egyptian history. In fact, with the wave of mysticism that swept over Asia Minor, over Greece, and over the lands around the Mediterranean, and as the simple faith in the old order declined, the superstitions of the past acquired fresh vigour. Divination of various kinds became the “fad” of cultured circles as well as of the ignorant masses, and the prominence assumed by astrology among these practices led to the application of the term “Chaldean wisdom” to the observation of the stars.

We must, however, bear in mind that the term as used by Greek and Roman writers means primarily astrology, and not astronomy. The Babylonian bârû priests, who left their native soil in search of a more profitable market elsewhere, found plenty of imitators who were too anxious to be known also as “Chaldeans,” though no doubt, for a time at least, the main supply of diviners in Greece, Rome, Asia Minor, and Egypt came from the Euphrates Valley.

IX

The movement which took place in Babylonia and Assyria when, through Persian, Greek, and other influences, the basis of the astrological system was weakened by the increasing importance of a genuine science growing out of the study of the phenomena of the heavens, reminds us of what happened in Judea. There, through the concentration of the legitimate Jahweh cult in the sanctuary at Jerusalem, the priests of the numerous local sanctuaries scattered throughout Palestine were deprived of their prestige, and to a large extent of their means of livelihood. These priests, known as Levites[50] “lost their job,” if the expressive colloquial phrase be permitted. The local sanctuaries were abandoned, but fortunately provision was made for the Levites in the priestly code. They were assigned to the lower menial duties at the temple in Jerusalem, and to act as attendants to the Jahweh priests—the kôhanîm ,—to be their “hewers of wood and drawers of water.” In Babylonia no Priestly Code was evolved to provide for the new order of things, and so when the bârû priests were replaced by the astronomers, the former left their homes, and, attracted by the prospect of successful careers in foreign lands, became the strolling magicians and soothsayers of antiquity.

The old, as almost invariably happens, partially survived by the side of the new; with the new alliance between astrology and astronomy, brought about by the accommodation of Babylonian methods to the Greek spirit, the old-time astrology continued in force and is represented by these “Chaldean” mountebanks. The pseudo-scientists adopted in time the phraseology and a superficial smattering of astronomical lore from the more genuine devotees of the study of the heavens, but their method remained essentially that of the old Babylonian astrologers. We have, thus, on the one hand, the serious cultivation of the newer astrology under the guise of genethlialogy, and, on the other, the continuation of the older form resting on a pseudo-scientific basis, but degraded to the rank of a dishonest profession through the “Chaldean” priests, who no longer found recognition in their native land.

With the entire collapse of astrology even in the form given to it by the Greek astronomers, through the newer scientific spirit of our own days which has destroyed the bond between the individual and the phenomena of the heavens, the divorce between astronomy and astrology became absolute and complete; but the “Chaldeans” of Greek and Roman times have their successors in the modern “astrologers” who, indifferent to the postulates of modern science, have adopted the jargon of scientific nomenclature, and still carry on a flourishing trade in the cities and country districts of Europe and America, and seem to justify the harsh dictum ascribed to Pope Paul IV.: mundus vult decipi ergo decipiatur.[51] Perhaps it is just as well that those who do not wish to be convinced should be deceived; and, after all, astrology is possibly the most innocent form of charlatanism in our modern life. We must, however, beware of the error of confusing these modem “astrologers” with the astrologer-astronomers of the Middle Ages with whom they naturally strive to claim relationship. This honourable guild of scientists was limited merely by the intellectual and scientific horizon of their day.

The astronomers of the Middle Ages who attached astrology to their scientific study of the heavens continued the traditions of the Greek astronomers, who adopted the astrology of the Babylonians and Assyrians as a practical application of the scientific astronomy long cultivated by them. The alliance was misguided but was not unholy. The modern “astrologers” who, through the law of demand and supply, pose as casters of individual horoscopes, may be thus directly traced back to the old bârû priests. Unscientific or pseudo-scientific, like their more immediate ancestors,—the “Chaldean” charlatans,—the astrologers of our days continue to ply a profession for which the tools are simple and the tricks complicated.

The question may arise, while following this story of the birth and growth of astrology, why exhume the superstitions and follies of the past? Of what use is it? Various are the answers. The path of mankind in its progress toward an unknown goal is devious, leading over wastes of error and falsehood. History is as full of failures as of achievements, and we must study the one as fully as the other. But perhaps the most satisfactory answer is suggested by the distinguished Bouche-Leclercq, who, raising this very question at the close of the introduction to his standard work on Greek astrology,[52] heroically declares— and what heart will not respond?—that it is not a waste of time to find out how other people have wasted theirs.

Plates:

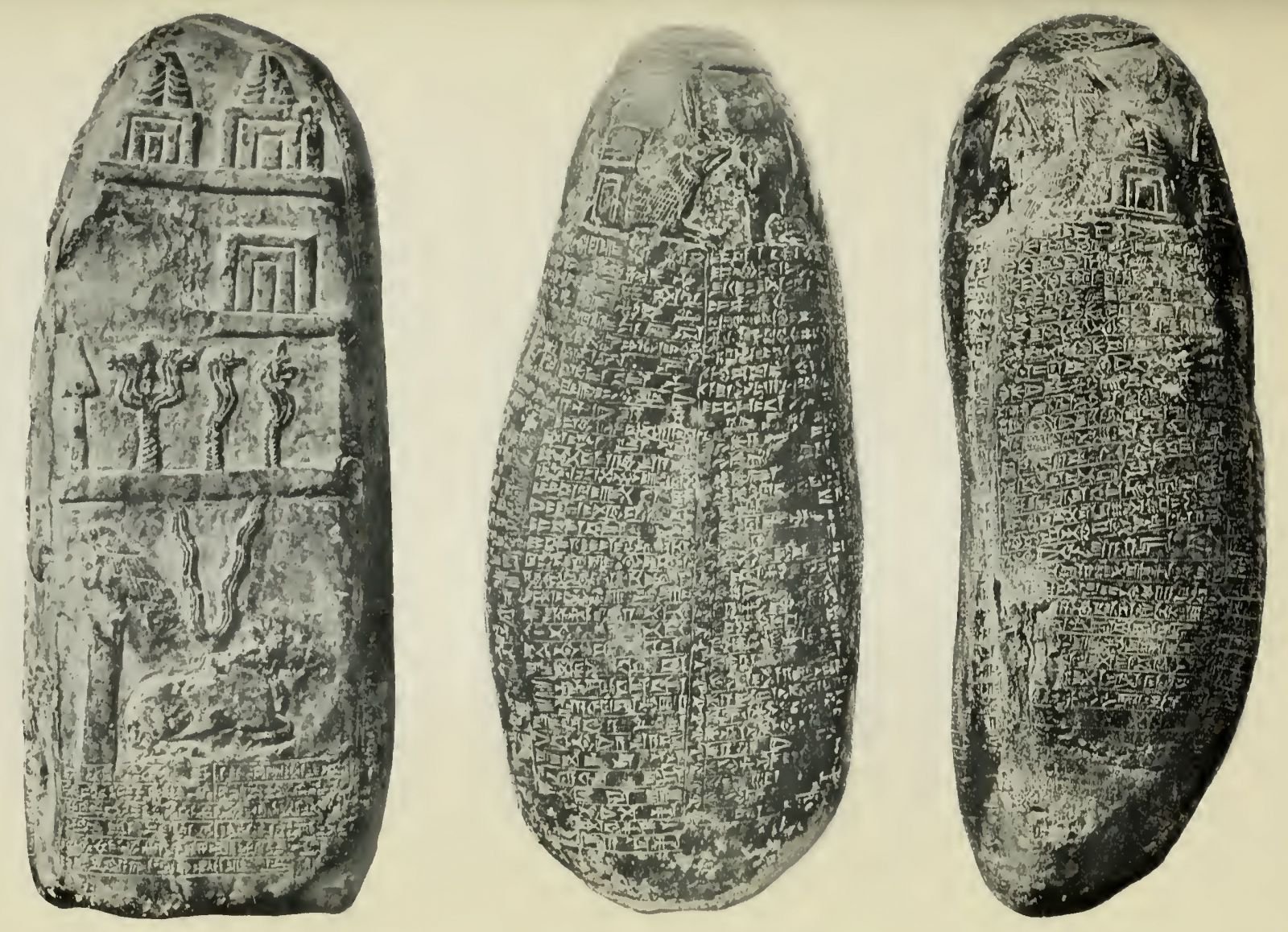

Plate 22

PI. 22, Boundary Stones, Showing Symbols of the Gods.

The one to the right is from the reign gf the Cassite King Nazi-maruttash (c. 1320 B.C.)—found at Susa and now in the Louvre.

The symbols shown on Face D (reproduced in the illustration) are:

- in the uppermost row, Anu and Enlil, symbolised by shrines with tiaras,

- in the second row—probably Ea [shrine with goat-fish and ram’s head (?)], and Ninlil (shrine with symbol of the goddess);

- third row—spear-head of Marduk, Ninib (mace with two lion heads); Zamama (mace with vulture head); Nergal (mace with lion's head);

- fourth row, Papsukal (bird on pole), Adad (or Ranunan—lightning fork on back of crouching ox);

- running along side of stone, the serpen t-god, Siru.

On Face C (not shown) are the symbols of

- Sin, the moon-god (crescent);

- Shamash the sun-god (solar disc);

- Ishtar (eight-pointed star);

- goddess Gula sitting on a shrine with the dog as her animal at her feet;

- Ishkhara (scorpion);

- Nusku, thefire-god (lamp).

The other two faces (A and B) are covered with the inscription. Nineteen gods are mentioned at the dose of the inscription, where these gods are called upon to curse any one who defaces or destroys the stone, or interferes with the provisions contained in the inscription. See Délégation en Perse Mémoires, vol. ii., PI. 18-19 and pp. 86-92 (also voL i., PI. XIV.,-XV., and pp. 170-172), and Hinke, A New Boundary Stone of Nebuchadrezzar, I., pp. 90-91 and p. 231.

The other boundary stone of which two faces are shown is dated in the reign of Marduk-baliddin, King of Babylonia (c. 1170 B.C.),— found at Susa and now in the Louvre. The symbols shown in the illustration are:

- Zamama (mace with the head of a vulture);

- Nebo (shrine with four rows of bricks on it, and homed dragon in front of it);

- Ninib (mace with two lion heads);

- Nusku, the god of fire Gamp);

- Marduk (spear-head);

- Bau (walking bird);

- Papsukal (bird perched on pole);

- Anu and Enlil (two shrines with tiaras);

- Sin, the moon-god (crescent). In addition there are (not distinguishable on the illustration):

- Ishtar (eight-pointed star),

- Shamash (sun disc),

- Ea (shrine with ram's head on it and goat-fish before it),

- Gula (sitting dog),

- goddess Ishkhara (scorpiqn),

- Nergal (mace with lion head),

- Adad (or Ramman—crouching ox with lightning fork on bade),

- Sim—the serpent god (coiled serpent on top of stone).

Pl. 22 —Continued

All these gods, with the exception of the last named, are mentioned in the curses at the close of the inscription together with their consorts. In a number of cases, (e. g., Shamash, Nergal, and Ishtar) minor deities of the same character are added which came to be regarded as forms of these deities or as their attendants; and lastly some additional gods notably Tammuz (under the form Damu), his sister Geshtin-Anna (or belit seri), and the two Cassite deities Shukamuna and Shumalia. In all forty-seven gods and goddesses are enumerated which may, however, as indicated, be reduced to a comparatively small number. See Delegation en Perse Memoir es, vol. vi., Pl. 9-10 and pp. 31-39; Hinke, op. cit., pp. 25 and 233-234.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See above, p. 162 seq.

[2]: