Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria

by Morris Jastrow | 1911 | 121,372 words

More than ten years after publishing his book on Babylonian and Assyrian religion, Morris Jastrow was invited to give a series of lectures. These lectures on the religious beliefs and practices in Babylonia and Assyria included: - Culture and Religion - The Pantheon - Divination - Astrology - The Temples and the Cults - Ethics and Life After Death...

Lecture I - Culture And Religion

I

FIFTY or sixty years ago the task of a lecturer called upon to deliver a course of six lectures on the religion of Babylonia and Assyria would have been comparatively simple. He could have told all that was known or that he knew in a single lecture, and could have devoted the remaining lectures to what he did not know—an innocent form of intellectual amusement, sometimes indulged in by lecturers of all times. During the past five or six decades, however, the material for the study has grown to such an extent that it is no longer possible, even were it desirable, to present the entire subject in a single course of lectures.[1] It is my purpose, therefore, in the present course to restrict myself to setting forth the more salient features in the beliefs and practices of a religion of antiquity that well merits the designation—remarkable. Its great age is of itself sufficient to call forth respect and interest. Although the civilisation that once flourished in the region of the Euphrates and Tigris is not so ancient as not many years ago it was fondly supposed to be by scholars whose enthusiasm outran their judgment,[2] yet we may safely say that three thousand years before our era, civilisation and religion in the Euphrates Valley had reached a high degree of development.

At that remote period some of the more important centres had already passed the zenith of their glory. Since thecourseof civilisation in this region flowed from south to north, it follows that the cities of the south are older than those of the northern part of the valley; and this assumption is fully confirmed by the results of excavations, as well as by historical data now at our disposal. The Babylonians themselves recognised this distinction between the south and the north, designating the former as Sumer (more correctly Shumer, though we shall use the simpler form)—which will at once recall the “plain of Shinar” in the Biblical story of the building of the tower[3]— and the latter as Akkad. The two in combination cover what is commonly known as Babylonia, but Sumer and Akkad were at one time as distinct from each other as were in later times Babylonia and Assyria. They stand, in fact, in the same geographical relationship to one other as do the latter; and it is significant that in the title “King of Sumer and Akkad,” which the rulers of the Euphrates Valley, from a certain period onward, were fond of assuming to mark their control of both south and north, it is Sumer, the designation of the southern area, which always precedes Akkad.

More important, however, than any geographical distinction is the ethnological contrast presented by Sumerians and Akkadians. To be sure, the designations themselves, applied in an ethnic sense, are purely conventional; but there is no longer any doubt of the fact that the Euphrates Valley from the time that it looms up on the historical horizon is the seat of a mixed population. The germ of truth in the time-honoured Biblical tradition, that makes the plain of Shinar the home of the human race and the seat of the confusion of languages, is the recollection of the fact that various races had settled there, and that various languages were there spoken. Indeed, we should be justified in assuming this, a priori; it may be put down as an axiom that nowhere does a high form of culture arise without the commingling of diverse ethnic elements. Civilisation, like the spark emitted by the striking of steel on flint, is everywhere the result of the stimulus evoked by the friction of one ethnic group upon another. Egyptian culture is the outcome of the mixture of Semitic with Hami-tic elements. Civilisation begins in Greece with the movements of Asiatic peoples—partly at least non-Aryan—across the JSgean Sea. In Rome we find the old Aryan stock mixed with a strange element, known as Etruscan. In modern times, France, Germany, and England furnish illustrations of the process of the commingling of diverse ethnic elements leading to advanced forms of civilisation, while in our own country the process is proceeding on so large a scale as to have suggested to a modern playwright the title of “The Melting Pot” for a play, depicting a new type of culture springing from the mixture of almost innumerable elements.

A pure race, if it exist at all outside of the brain of some ethnologists, is a barren race. Mixed races, and mixed races alone, bring forth the fruit that we term civilisation,—with social, religious, and intellectual progress. Monuments also bear witness, in ethnic types, in costumes, and in other ways, to the existence of two distinct classes in the population of the Euphrates Valley—Semites or Akkadians, and non-Semites or Sumerians. The oldest strongholds of the Semites are in the northern portion, those of the Sumerians in the southern. It does not, however, necessarily follow that the Sumerians were the oldest settlers in the valley; nor does the fact that in the oldest historical period they are the predominating factor warrant the conclusion. Analogy would, on the contrary, suggest that they represent the conquering element, which by its admixture with the older settlers furnished the stimulus to an intellectual advance, and at the same time drove the older Semitic population farther to the north.

We are approaching a burning problem in regard to which scholars are still divided, and which, in some of its aspects, is not unlike the Rabbinical quibble whether the chicken or the egg came first. It is the lasting merit of the distinguished Joseph Halevy of Paris to have diverted Assyriological scholarship from the erroneous course into which it was drifting a generation ago, when, in the older Euphratean culture, it sought to differentiate sharply between Sumerian and Akkadian elements.[4] Preference was given to the non-Semitic Sumerians, to whom was attributed the origin of the cuneiform script. The Semitic (or Akkadian) settlers were supposed to be the borrowers also in religion, in forms of government, and in civilisation generally, besides adopting the cuneiform syllabary of the Sumerians, and adapting it to their own speech. Hie Sumer, hie Akkad! Halevy maintained that many of the features in this syllabary, hitherto regarded as Sumerian, were genuinely Semitic; and his main contention is that what is known as Sumerian is rnerely an older form of Semitic writing, marked by the larger use of ideographs or signs to express words, in place of the later method of phonetic writing wherein the signs employed have syllabic values.[5]

While an impartial review of the still active controversy demands the conclusion that Halevy has not succeeded in convincing scholars that there is no such thing as a Sumerian language, yet, in addition to demonstrating that, even in its oldest phase, the cuneiform syllabary contains unquestionable Semitic elements, he has also made it clear that many texts— particularly those of a religious character—, once regarded as Sumerian originals, are Semitic in character. The “Sumerian” form of writing was intended purely for the eye, and represented the ideographic method of writing such texts, further complicated by a super-layer of more or less artificial devices. This applies even to votive and other inscriptions of the oldest period. To maintain in reply that the pure Sumerian period lies still further back, is to beg the question.

On the other hand, the existence of a Sumerian people (or whatever name we may propose to give to the earliest non-Semitic settlers) being an undeniable fact in view of the ethnic evidence furnished by the monuments,[6] we must perforce assume that there was also a Sumerian language; and we are certainly justified in looking for traces of this language in inscriptions coming from the strongholds of the Sumerians. Making full allowance for possible, or probable, Semitic elements in the oldest “Sumerian” inscriptions, there yet remain many features not to be satisfactorily accounted for on the supposition that they are artificial devices, introduced in the course of the adaptation of a hieroglyphic script to express greater niceties of thought. A substratum remains requiring the assumption that side by side with the ideographic method of writing the old Semitic speech, developing in the course of time to a phonetic and mixed phonetic-ideographic script, we have also inscriptions which must be regarded as non-Semitic, and that likewise show two varieties—ideographic and phonetic modes of expression.

But in accepting this conclusion we have not yet settled the question whether the script is due to the Semitic or to the non-Semitic settlers. Like every other script, the cuneiform characters revert to a purely hieroglyphic form. The pictures represented, so far as these have been determined, do not carry us outside of the Euphrates Valley. A form of writing in the earliest pictorial style being applicable to any language, it is conceivable that the script of the Euphrates Valley may have been used by Semites and non-Semites alike; or, in other words, the pictorial representation of facts or ideas might have been read or translated into either non-Semitic Sumerian or Semitic Akkadian, using these terms for the languages of the two ethnic groups. The period of differentiation would set in when it became necessary to express thoughts or abstract ideas more definitely, and in nicer shades than is possible in a purely pictorial script, which has obviously definite limitations. Granting that the origin of the Euphratean civilisation is due to the combination of the Semitic and non-Semitic elements of the population, the script would likewise be the joint product of these two elements; and it is conceivable that, starting in this way, writing should develop in two directions—one calculated to adapt the script to express the greater niceties of thought in Sumerian, the other to express them in Akkadian, while both Sumerian and Akkadian would retain many elements in common in the general endeavour to give expression to thought in writing.

At the same time, the two modes would exert upon each other an influence commensurate with the general process of mixture that gives to the religion and culture the harmonious combination of diverse factors. Some such theory as this, which would make the developed script the result of the intellectual activity of both elements of the population, and not the exclusive achievement of one and adopted by the other, may be eventually found to satisfy best the conditions involved, though it must be admitted that as yet neither this theory nor any other can be advanced as absolutely definite and final. The development of the script in two directions would not necessarily proceed pari passu . The one or the other might be accelerated or retarded by various factors. Throughout the different phases of development, there would always be at each stage the tendency to a mutual influence, until finally, with the definite predominance in the culture of one element—which in the case in question proved to be the Semitic,—the development in one direction would be arrested, while in the other it would proceed uninterruptedly.

It is perhaps idle to indulge the hope of ever being able to follow details of a process so complicated as the transformation of a script from its oldest hieroglyphic aspect to a form verging closely on an alphabetic system. The task is particularly hopeless in the case of the cuneiform script, because of this commingling of Sumerian with Akkadian elements which we encounter from the beginning. While, naturally, it is reasonable to expect that further progress towards the solution of the problem will be made— and indeed unexpected material throwing light on the subject may at any time be discovered,—it is safe to predict that this progress will serve also to illustrate still further the composite character of the Euphratean civilisation as a whole.

II

The earliest historical period known to us, which, roughly speaking, is from 2800 B.C., to 2000 B.C., may be designated as a struggle for political ascendency between the Sumerian (or non-Semitic), and the Akkadian (or Semitic) elements. The strongholds of the Sumerians at this period were in the south, in such centres as Lagash, Kish, Umma, Uruk, Nippur, and Ur, those of the Semites in the north, particularly at Agade, Sippar, and Babylon, with a gradual extension of the Semitic settlements still farther north towards Assyria. It does not follow, however, from this that the one element or the other was absolutely confined to any one district. The circumstance that even at this early period we find the same religious observances, the same forms of government, the same economic conditions in south and north, is a testimony to the intellectual bond uniting the two districts, as also to the two diverse elements of the population. The civilisation, in a word, that we encounter at this earliest period is neither Sumerian nor Akkadian but Sumero-Akkadian, the two elements being so combined that it is difficult to determine what was contributed by one element and what by the other; and this applies to the religion and to the other phases of this civilisation, just as to the script.

When the curtain of history rises on the scene, we are long past the period when the Semitic hordes, coming probably from their homes in Arabia,[7] and the Sumerians, whose origin is with equal probability to be sought in the mountainous regions to the east and north-east of the Euphrates Valley,[8] began to pour into the land. The attraction that settled habitations in a fertile district have for those occupying a lower grade of civilisation led to constant or, at all events, to frequent reinforcements of both Semites and non-Semites. The general condition that presents itself in the earliest period known to us is that of a number of principalities or little kingdoms in the Euphrates Valley, grouped around some centre whose religious significance always kept pace with its political importance, and often surpassed and survived it. Rivalry between these centres led to frequent changes in the political kaleidoscope, now one, now another claiming a certain measure of jurisdiction or control over the others. Of this early period we have as yet obtained merely glimpses. Titles of rulers with brief notices of their wars and building operations form only too frequently the substance of the information to be gleaned from votive inscriptions, and from dates attached to legal and business documents. This material suffices, however, to secure a general perspective. In the case of two of these centres, Lagash and Nippur, thanks to extensive excavations conducted there,[9] the framework can be filled out with numerous details. The general conditions existing at Lagash and Nippur may be regarded as typical for the entire Euphrates Valley in the earliest period.

The religion had long passed the animistic stage when all powers of nature were endowed with human purposes and indiscriminately personified. The process of selection (to be explained more fully in a future lecture) had singled out of the large number of such personified powers a limited number, which, although associated in each instance with a locality, were, nevertheless, also viewed as distinct from this association, and as summing up the chief Powers in nature whereon depended the general welfare and prosperity. Growing political relationships between the sections of the Euphrates Valley accelerated this process of selection, and furthered a combination of selected deities into the semblance, at least, of a pantheon partially organised, and which in time became definitely constituted. The patron deities of cities that rose to be centres of a district absorbed the local numina of the smaller places. The names of the latter became epithets of the deities politically more conspicuous, so that, e.g., the sun-god of a centre like Lagash became almost an abstract and general personification of the sun itself. Similarly, the moon-god of Ur received the names and attributes of the moon-gods associated with other places.

A marked and deep religious spirit pervades throughout the culture of the time. The rulers held their authority directly from the patron deities— “by the grace of God,” as we should now say. They do not generally go so far as to claim divine descent, but they closely approach it. They regard themselves as chosen by the will of the gods. Their strength is derived from Ningirsu, they are nourished by Nin-Kharsag, they are appointed by the goddess Innina. When they go to war the gods march at their side, and the booty is dedicated to these protecting powers. The political fortunes, and indeed the general culture, are thus closely bound up with the religion. Each centre had a chief deity whose position in the pantheon kept pace with the political growth of the centre. At Lagash this chief deity was Ningirsu, a solar deity; at Nippur it was Enlil, originally a personification of the storm; at Cuthah, it was Nergal, likewise a solar deity, and at Ur it was Sin, the moon-god. The chief edifice in the capital of the principality is the temple of the patron deity, alongside of which are smaller sanctuaries within the sacred area, dedicated to the gods and goddesses associated with the main cult. Art is developed around the cult. Such artistic skill was largely employed in the fashioning of votive objects; and even where the rulers erected statues of themselves, these were dedicated to some deity and intended to symbolise the pious devotion of the god’s representative on earth. As further emphasising the bond between religious and secular conditions we find the palaces of rulers at all times adjoining the temple.

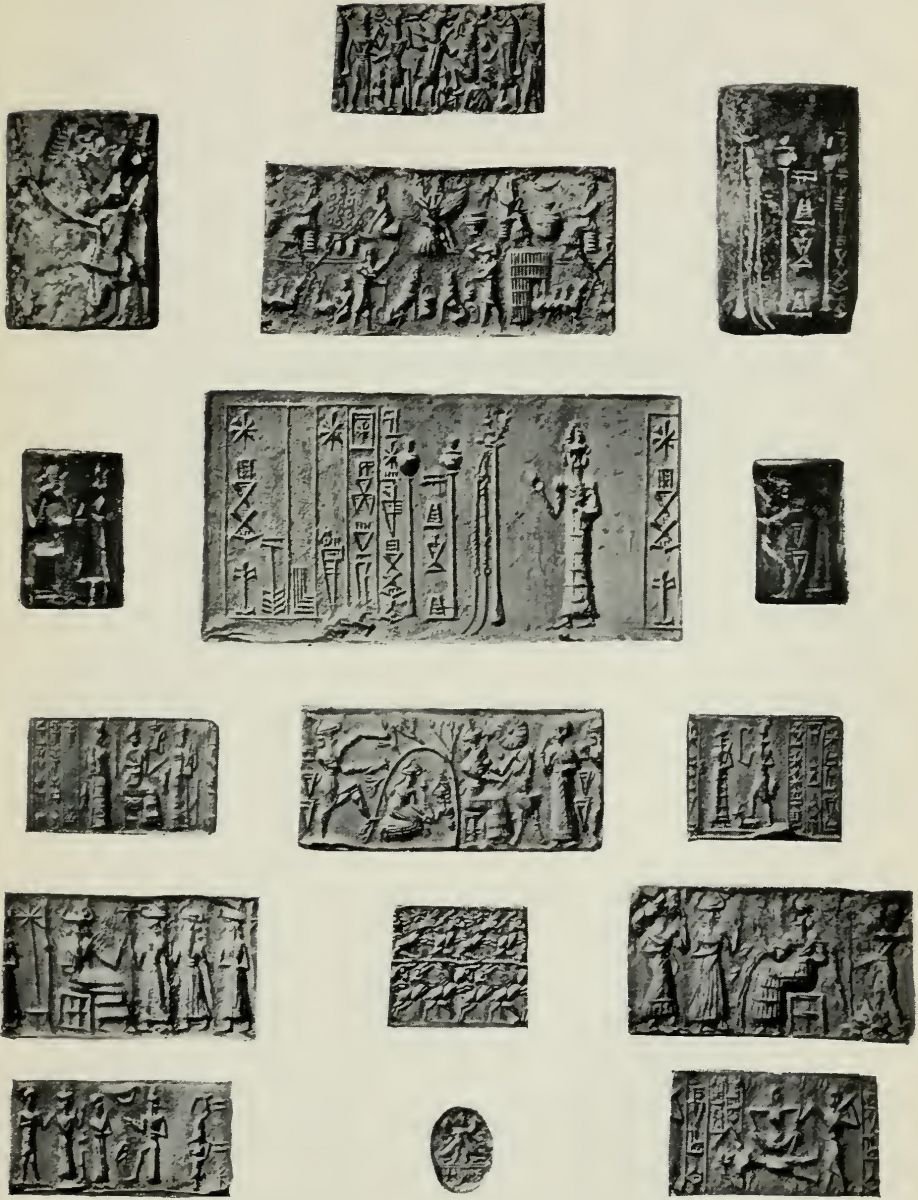

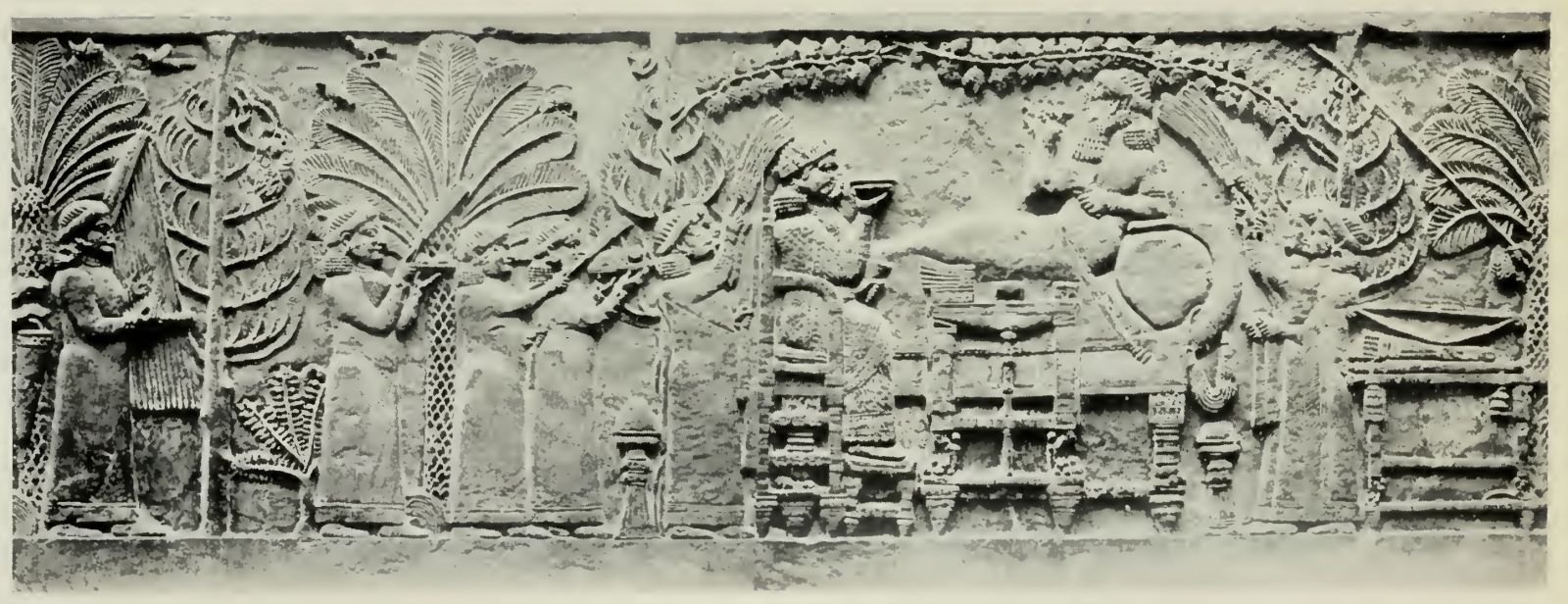

The architecture of both temple and palace is massive and, in consequence of the lack of a hard building-material in the Euphrates Valley, it is perhaps natural that the brick constructions developed in the direction of hugeness rather than of beauty. The drawings on limestone votive tablets and on other material during this early period are generally crude. More skill is displayed in incisures on seal cylinders[10] of various kinds of material, bone, shell, quartz, chalcedony, lapis-lazuli, hematite, marble, and agate. Though serving the purely secular purpose of identifying an individual’s personal signature to a business document—written on clay as the usual writing-material—these cylinders incidentally illustrate the bond between culture and religion by their engraved designs, which are invariably of a religious character, —such as the adoration of deities, sacrificial scenes, or representations of myths or mythical personages. Though marred frequently by grotesqueness, the metal work—in copper, bronze, or silver—is on the whole of a relatively high order, particularly in the portrayal of animals. The human face remains, however, without expression, even where, as in the case of statues chiselled out of the hard diorite,[11] imported from Arabia, the features are carefully worked out.

The population was largely agricultural, but as the cities grew in size, naturally, industrial pursuits and commercial activity increased. Testimony to brisk trading in fields and field products, in houses and woven stuffs, in cattle and slaves is furnished by the large number of business documents of all periods from the earliest to the latest, embracing such a variety of subjects as loans, rents of fields and houses, contracts for work, hire of workmen and slaves, and barter and exchange of all kinds. Even in the purely business activity of the country, the bond between culture and religion is exemplified by the large share taken by the temples in the commercial life. The temples had large holdings in land and cattle. They loaned money and engaged in mercantile pursuits of various kinds; so that a considerable portion of the business documents in both the older and the later periods deal with temple affairs, and form part of the official archives of the temples.[12]

The prominent influence exerted by religion in the oldest period finds a specially striking illustration in the position acquired by the city of Nippur—certainly one of the oldest centres in the Euphrates Valley. So far as indications go, Nippur never assumed any great political importance, though it is possible that it did so at a period still beyond our ken. But although we do not learn of any jurisdiction exercised by her rulers over any considerable portion of the Euphrates Valley, we find potentates from various parts of Babylonia and subsequently also the Assyrian kings paying homage to the chief deity of the place, Enlil.[13] To his temple, known as E-Kur, “mountain house,” they brought votive objects inscribed with their names. Rulers of Kish, Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Agade are thus represented in the older period, and it would appear to have been almost an official obligation for those who claimed sovereignty over the Euphrates Valley to mark their control by some form of homage to Enlil, the name of whose temple became in the course of time a general term for “sanctuary.”[14] The patron deities of other centres, such as Ningirsu of Lagash, Nergal of Cuthah, Sin of Ur, Shamash of Sippar, and Marduk of Babylon, were represented by shrines or temples within the sacred quarter of Nippur; and the rulers of these centres rarely failed to include in their titles some reference to their relationship to Enlil and to his consort Ninlil, or, as she was also called, Nin-Kharsag, “the lady of the mountain.”

The position thus occupied by Nippur was not unlike that of the sacred places of India like Benares, or like that of Rome as the spiritual centre of Christendom during the Middle Ages. Sumerians and Semites alike paid their obeisance to Enlil, who through all the political changes retained, as we shall see, the theoretical headship of the pantheon. When he is practically replaced by Marduk, the chief god of the city of Babylon, after Babylon had become the political centre of the entire district, he transfers his attributes to his successor. As the highest homage paid to Marduk, he is called the bel or “lord” par excellence in place of Enlil, while Marduk’s consort becomes Ninlil, like the consort of Enlil.

The control of Nippur was thus the ambition of all rulers from the earliest to the latest periods; and the plausible suggestion has been recently made that the claim of divinity, so far as it existed in ancient Babylonia,[15] was merely intended as an expression of such control—an indication that a ruler who had secured the approval of Enlil might regard himself as the legitimate vicegerent of the god on earth, and therefore as partaking of the divine character of Enlil himself.

This close relationship between religion and culture, in its various aspects—political, social, economic, and artistic,—is thus the distinguishing mark of the early history of the Euphrates Valley that leaves its impress upon subsequent ages. Intellectual life centres around religious beliefs, both those of popular origin and those developed in schools attached to the temples, in which, as we shall see, speculations of a more theoretical character were unfolded in amplification of popular beliefs.

III

As already pointed out, even in the oldest period to which our material enables us to trace the history of the Euphrates Valley, we witness the conflict for political control between Sumerians and Akkadians (that is between non-Semites and Semites). Lagash, Nippur, Ur, and Uruk are ancient Sumerian centres, but near the border-line between the southern and the northern sections of this valley a strong political centre is established at Kish, which foreshadows the growing predominance of the Semites. The rulers sometimes assume the title of “king,” sometimes are known by the more modest title of “chief,”[16] a variation that suggests frequent changes of political fortunes. The population is depicted on the monuments as Sumerian, and yet among the rulers we find one bearing a distinctly Semitic name,[17] while some of the inscriptions of the rulers of Kish are clearly to be read as Semitic, and not as Sumerian. It is, therefore, not surprising to find the Semitic kings of Akkad, circa 2500 B.C., and even before the rise of Kish, reaching a position of supremacy that extended their rule far into the south, besides passing to the north, east, and west, far beyond the confines of Babylonia and Assyria.

There are two names in this dynasty of Akkad with its centre at Agade that stand forth with special prominence—Sargon, and his son Naram-Sin. Sargon[18] in fact marks an epoch in the history of the Euphrates Valley. He is the first conqueror to inaugurate a policy of wide conquest that eventually gave to Babylonia and subsequently to Assyria a commanding position in the ancient world. While retaining his captial at Agade, he brings into prominence the neighbouring Sippar by devoting himself to the service of the sun-god Shamash at that place; and he either founds or enlarges the city Babylon which a few centuries later became the captial of the United Euphrates Valley; its frame was destined to outlast the memory of all the other centres of the south, and to become synonymous with the culture and religion of the entire district. The old enemy of Sumer on the east, known as Elam, with which Sumerian rulers had many a conflict , was forced to yield to the powerful Sargon. Far to the north the principality of Subartu—the later Assyria—and still father north the district known as Guti acknowledged the rule of Sargon and of his successors. The land to the west up to the Mediterranean coast, known under the general designation of Amurru,[19] was also claimed by Sargon. The rulers of Lagash humbly call themselves the “servants” of the powerful conqueror; Cuthah, Uruk, Opis, and Nippur in the south, Babylon and Sippar in the north, are among the centres in the Euphrates Valley, specifically named by Sargon as coming under his sway. He advances to Nippur, and, by assuming the title “King of Akkad and of the Kingdom of Enlil,” announces his control of the whole of Sumer and Akkad.

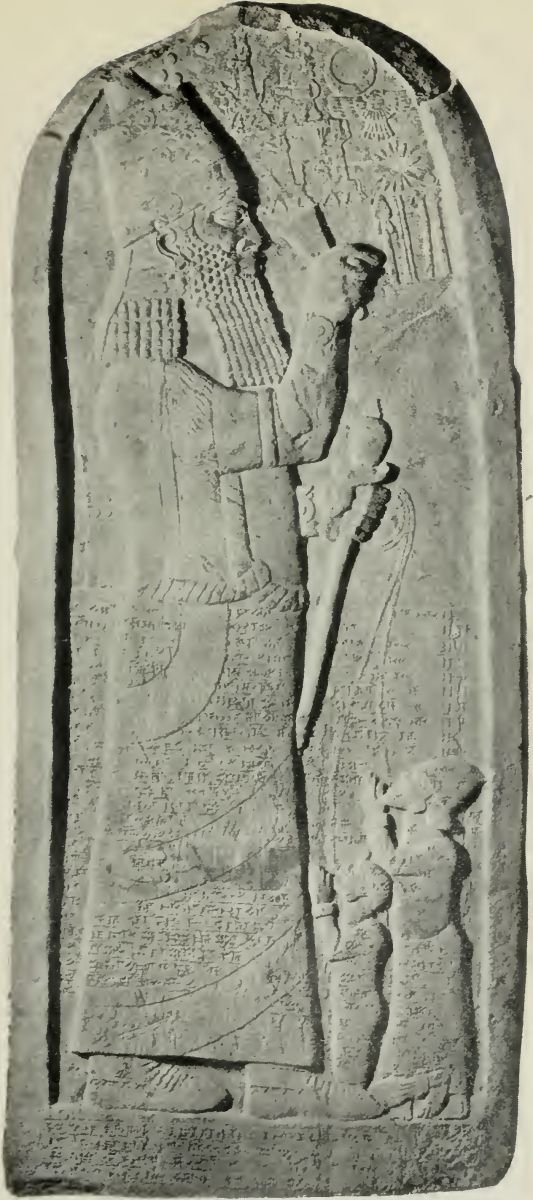

The times must have been ripe for a movement on so large a scale. As so often happens, the political upheaval was followed by a strong intellectual stimulus which shows itself in a striking advance in Art. One of the most remarkable monuments of the Euphrates Valley dates from this period. It depicts Naram-Sin, the son of Sargon, triumphing over Elam; and it seems an irony of fate that this magnificent sculptured stone should have been carried away, centuries later, as a trophy of war by the Elamites in one of their successful incursions into the Euphrates Valley.[20] In triumphant pose Naram-Sin is represented in the act of humiliating the enemy by driving a spear through the prostrate body of a soldier, pleading for mercy. The king wears the cap with the upturned horns that marks him as possessing the attributes of divine power. He continues the conquests of his father, and penetrates even into Arabia,[21] so that he could well lay claim to the high-sounding title which he assumes of “King of the Four Regions.”[22] The glory of this extensive kingdom thus established by Sargon and Naram-Sin was, however, of short duration. Agade was obliged, apparently, to yield first to Kish.

This happened not long after Naram-Sin’s death but, what is more significant, within about two centuries the Sumerians succeeded in regaining their prestige; and with their capital at Ur, an ancient centre of the moon-cult, Sumerian rulers emphasise their sovereignty of both south and north by assuming the title “King of Sumer and Akkad.” Ur-Engur, the founder of the dynasty (ca. 2300 B.C.), which maintained its sway for 117 years, is the first to assume this title, which, to be sure, is not so grandiloquent as that of “King of the Four Regions,” but rests on a more substantial foundation. It represents a realm that could be controlled, while a universal empire such as Sargon and Naram-Sin claimed was largely nominal—a dream in which ambitious conquerors from Sargon to Napoleon have indulged, and which could at the most become for a time a terrifying nightmare to the nations of the world.

With Sargon and Ur-Engur we thus enter on a new era. Instead of a rivalry among many centres for political supremacy over the south or the north, we have Semites and Sumerians striving for complete control of the entire valley, with a marked tendency to include within their scope the district to the north of Akkad. This district, as a natural extension consequent upon the spread of the Sumero-Akkadian culture, was eventually to become a separate principality that in time reversed the situation, and began to encroach upon the independence of the Euphrates Valley.

Two new factors begin about this time, and possibly even earlier, to exercise a decided influence in further modifying the Sumero-Akkadian culture; one of these is the Amoritish influence, the other is a conglomeration of peoples collectively known as the Hittites. From the days of Sargon we find frequent traces of the Amorites; and there is at least one deity in the pantheon of this early period who was imported into the Euphrates Valley from the west, the home of the Amorites. This deity was a storm god known as Adad,[23] appearing in Syria and Palestine as Hadad. According to Professor Clay,[24] most of the other prominent members of what eventually became the definitely constituted Babylonian pantheon betray traces of having been subjected to this western influence. Indeed, Professor Clay goes even further and would ascribe many of the parallels between Biblical and Babylonian myths, traditions, customs, and rites to an early influence exerted by Amurru (which he regards as the home of the northern Semites) on Babylonia, and not, as has been hitherto assumed, to a western extension of Babylonian culture and religion.

It is too early to pronounce a definite opinion on this interesting and novel thesis; but, granting that Professor Clay has pressed his views beyond legitimate bounds, there can no longer be any doubt that in accounting for the later and for some of the earlier aspects of the Sumero-Akkadian civilisation this factor of Amurru must be taken into account; nor is it at all unlikely that long before the days of Sargon, a wave of migration from the north and north-west to the south and south-east had set in, which brought large bodies of Amorites into the Euphrates Valley as well as into Assyria. The circumstance that, as has been pointed out, the earliest permanent settlements of Semites in the Euphrates Valley appear to be in the northern portion, creates a strong presumption in favour of the view which makes the Semites come into Babylonia from the north-west.[25]

Hittites do not make their appearance in the Euphrates Valley until some centuries after Sargon, but since it now appears[26] that ca. 1800 B.C. they had become strong enough to invade the district, and that a Hittite ruler actually occupied the throne of Babylonia for a short period, we are justified in carrying the beginnings of Hittite influence back to the time at least of the Ur dynasty. This conclusion is strengthened by the evidence for an early establishment of a Hittite principality in north-western Mesopotamia, known as Mitanni, which extended its sway as early at least as 2100 B.C. to Assyria proper.

Thanks to the excavations conducted by the German expedition[27] at Kalah-Shergat (the site of the old capital of Assyria known as Ashur), we can now trace the beginnings of Assyria several centuries further back than was possible only a few years ago. The proper names at this earliest period of Assyrian history show a marked Hittite or Mitanni influence in the district, and it is significant that Ushpia, the founder of the most famous and oldest sanctuary in Ashur, bears a Hittite name.[28] The conclusion appears justified that Assyria began her rule as an extension of Hittite control. With a branch of the Hittites firmly established in Assyria as early as ca. 2100 B.C., we can now account for an invasion of Babylonia a few centuries later. The Hittites brought their gods with them, as did the Amorites, and, with the gods, religious conceptions peculiarly their own. Traces of Hittite influence are to be seen e.g., in the designs on the seal cylinders, as has been recently shown by Dr. Ward,[29] who, indeed, is inclined to assign to this influence a share in the religious art, and, therefore, also in the general culture and religion, much larger than could have been suspected a decade ago.

Who those Hittites were we do not as yet know. Probably they represent a motley group of various peoples, and they may turn out to be Aryans. It is quite certain that they originated in a mountainous district, and that they were not Semites. We should thus have a factor entering into the Babylo-nian-Assyrian civilisation—leaving its decided traces in the religion—which was wholly different from the two chief elements in that civilisation—the Sumerian and the Akkadian.

The Amorites have generally been regarded as Semites. Professor Clay, we have seen, would regard Amurru as, in fact, the home of a large branch of the Semites; yet the manner in which the Old Testament contrasts the Canaanites—the old population of Palestine dispossessed by the invading Hebrews— with the Amorites, raises the question whether this contrast does not rest on an ethnic distinction. The Amoritish type as depicted on Egyptian monuments[30] also is distinct from that of the Semitic inhabitants of Palestine and Syria. It is quite within the range of possibility that the Amorites, too, represent another non-Semitic factor further complicating the web of the Sumero-Akkadian culture, though it must also be borne in mind that the Amorites, whatever their original ethnic type may have been, became commingled with Semites, and in later times are not to be distinguished from the Semitic population of Syria.

Leaving these problems regarding Amorites and Hittites aside as not yet ripe for solution, we may content ourselves with a recognition of these two additional factors in the further development of the political and religious history of the Euphrates Valley and of its northern extension known as Assyria.

IV

For some time after Ur-Engur had established a powerful dynasty at Ur, the Sumerians seem to have had everything their own way. His son and successor, Dungi, wages successful wars, like Sargon and Naram-Sin, with the nations around and again assumes the larger title of “King of the Four Regions.” He hands over his large realm, comprising Elam on the one side, and extending to Syria on the other, to his son Bur-Sin. We know but few details of the reign of Bur-Sin and of the two other members of the Ur dynasty that followed him, but the indications are that the Sumerian reaction, represented by the advent of the Ur dynasty, though at first apparently complete, is in reality a compromise. Semitic influence waxes stronger from generation to generation, as is shown by the steadily growing preponderance of Semitic words and expressions in Sumerian documents. The Semitic culture of Akkad not only colours that of Sumer, but permeates it so thoroughly as largely to eradicate the still remaining original and unassimilated Sumerian elements. The Sumerian deities as well as the Sumerians themselves adopt the Semitic form of dress.[31] We even find Sumerians bearing Semitic names; and in another century Semitic speech, which we may henceforth designate as Babylonian, became predominant.

On the overthrow of the Ur dynasty the political centre shifts from Ur to Isin. The last king of the Ur dynasty is made a prisoner by the Elamites, who thus again asserted their independence. The title “King of the Four Regions” is discarded by the rulers of Isin, and although they continue to use the title “King of Sumer and Akkad,” there are many indications that the supremacy of the Sumerians is steadily on the wane. They were unable to prevent the rise of an independent state with its centre in the city of Babylon under Semitic control, and about the year 2000 B.C., the rulers of that city begin to assume the title “King of Babylon.” The establishment of this so-called first dynasty of Babylon definitely foreshadows the end of Sumerian supremacy in the Euphrates Valley, and the permanent triumph of the Semites. Fifty years afterward we reach another main epoch, in many respects the most important, with the accession of Hammurapi[32] to the throne of Babylon as the sixth member of the dynasty. During his long reign of forty-two years (ca. 1958-1916 B.C.), Hammurapi fairly revolutionised both the political and the religious conditions.

The name of Hammurapi deserves to be emblazoned in letters of gold on the scroll of fame. His predecessors, to be sure, had in part paved the way for him. Availing themselves of the weakness of the south, which had again been split up into a number of independent principalities—Ur, Isin, Larsa, Kish, and Uruk,—they had been successful not only in warding off attacks from the outside upon their own district, but in forcing some of these principalities to temporary subjection. Still, there was much left for Hammurapi to do before he could take the titles “King of Sumer and Akkad” and “King of the Four Regions”; and it was not until the thirtieth year of his reign that, by the successful overthrow of the old-time enemy, Elam, and then of his own and his father’s formidable rival Rim-Sin, the king of Larsa, he could claim to be the absolute master of the entire Euphrates Valley, and of the adjoining Elam.[33] After that, he directed his attention to the north and north-west, and before the end of his reign his dominion embraced Assyria, and extended to the heart of the Hittite domain in the north-west. But Hammurapi is far more than a mere conqueror. He is the founder of a real empire—welding north and south into a genuine union, which outlasts the vicissitudes of time for almost fifteen hundred years. The permanent character of his work is due in part at least to the fact that he is not only “the mighty king, the king of Babylon,” but also “the king of righteousness,” as he calls himself, devoted to promoting the welfare j

of his subjects, and actuated by the ambition that every one who had a just cause should come to him as a son to a father. He establishes the unity of the country on a firm basis by the codification of the existing laws and by a formal promulgation of this code throughout his empire as the authoritative and recognised guide in government. The importance of this step can hardly be overestimated. If from this time on we speak of a Babylonian empire which, despite frequent changes of dynasties, despite a control of Babylonia for over half a millennium (ca. 1750-1175 B.C.), by a foreign people known as the Cassites, survived with its identity clearly marked, down to the taking of Babylon by Cyrus in 539 B.C., and in some measure even to the advent of Alexander the Great in 331 B.C., —it is due, in the first instance, to the unifying power exerted by Hammu-rapi’s code, the fortunate discovery of which in 1891[34] has contributed so much to our knowledge of the conditions of culture and religion in ancient Babylonia. It is no exaggeration to say that this code created the Babylonian people, just as, about six centuries later, the great leader Moses formed the Hebrew nation out of heterogeneous elements by giving them a body of laws, civil and religious.[35] The code established a bond of union between Sumer and Akkad of a character far more binding than could be brought about by the mere subjection of the south to the north. Through this code whatever distinctions still existed between Sumerians and Akkadians were gradually wiped out. From the time of Hammurapi on, we are justified in speaking of Babylonians, and no longer of Sumerians and Akkadians.

The code illustrates in a striking manner the close relationship between culture and religion in the Euphrates Valley which forms our main theme in this lecture. The eloquent introduction will illustrate the spirit that pervades it :

When the supreme Anu, king of the Annunaki, and Enlil» the lord of heaven and earth, who fixes the destiny of the land, had committed to Marduk, the first-born of Ea, the rule of all mankind, making him great among the Igigi, gave to Babylon his supreme name, making it pre-eminent in the regions (of the world), and established therein an enduring kingdom, firm in its foundation like heaven and earth—at that time they appointed me, Hammurapi, the exalted ruler, the one who fears the gods, to let justice shine in the land, to destroy the wicked and unjust that the strong should not oppress the weak, that I should go forth like the sun over mankind.

Hammurapi then passes on to an enumeration of all that he did for the various cities of his realm—

- for Nippur,

- Durilu,

- Eridu,

- Babylon,

- Ur,

- Sippar,

- Larsa,

- Uruk,

- Isin,

- Kish,

- Cuthah,

- Borsippa,

- Dilbat,

- Lagash,

- Adab,

- Agade,

- Nineveh,

- and the distant Hallab.[36]

It is significant that he refers to his conquests only incidentally, and lays the chief stress upon what he did for the gods and for men, enumerating the temples that he built and beautified, the security that he obtained for his subjects, the protection that he granted to those in need of aid.

“Law and justice,” he concludes,

“I established in the land and promoted the well-being of the people.”[37]

The religious and ethical spirit is thus the impelling power of the most important accomplishment in Hammurapi’s career; and the interdependence of culture and religion finds another striking illustration in the changed aspect that the pantheon and the cult assumed after the period of Hammurapi. He names at the beginning of his code the two deities, Anu and Enlil. Both were, originally, local gods, Anu the patron deity of Uruk, Enlil the chief deity of Nippur. Through a process that will be set forth in detail in the next lecture, Anu and Enlil became in the course of time abstractions, summing up, as it were, the chief manifestations of divine power in the universe. Anu, from being originally a personification of the sun, becomes the god of heaven, while Enlil, starting out as a storm-god, takes on as the theoretical head of the pantheon the traits of other gods, and becomes the god in control of the earth and of the regions immediately above it. The two therefore stand for heaven and earth, and to them there is joined, as a third member, Ea. Originally, the local deity of another ancient centre (Eridu, on or nearby the Persian Gulf[38]) and a god of the water, Ea became the symbol of the watery element in general.

Anu, Enlil, Ea, presiding over the universe, are supreme over all the lower gods and spirits combined as Annunaki and Igigi, but they entrust the practical direction of the universe to Marduk, the god of Babylon. He is the first-born of Ea, and to him as the worthiest and fittest for the task, Anu and Enlil voluntarily commit universal rule. This recognition of Marduk by the three deities, who represent the three divisions of the universe—heaven, earth, and all waters,—marks the profound religious change that was brought about through the advance of Marduk to a commanding position among the gods. From being a personification of the sun with its cult localised in the city of Babylon, over whose destinies he presides, he comes to be recognised as leader and director of the great Triad. Corresponding, therefore, to the political predominance attained by the city of Babylon as the capital of the united empire, and as a direct consequence thereof, the patron of the political centre becomes the head of the pantheon to whom gods and mankind alike pay homage. The new order must not, however, be regarded as a break with the past, for Marduk is pictured as assuming the headship of the pantheon by the grace of the gods, as the legitimate heir of Anu, Enlil, and Ea.

There are also ascribed to him the attributes and powers of all the other great gods, of Ninib, Shamash, and Nergal, the three chief solar deities, of Sin the moon-god, of Ea and Nebo, the chief water deities, of Adad, the storm-god, and especially of the ancient Enlil of Nippur. He becomes like Enlil “the lord of the lands,” and is known pre-eminently as the bel or “lord.” Addressed in terms which emphatically convey the impression that he is the one and only god, whatever tendencies toward a true monotheism are developed in the Euphrates Valley, all cluster about him.

The cult undergoes a correspondingly profound change. Hymns, originally composed in honour of Enlil and Ea, are transferred to Marduk. At Nippur, as we shall see,[39] there developed an elaborate lamentation ritual for the occasions when national catastrophes, defeat, failure of crops, destructive storms, and pestilence revealed the displeasure and anger of the gods. At such times earnest endeavours were made, through petitions, accompanied by fasting and other symbols of contrition, to bring about a reconciliation with the angered Powers. This ritual, owing to the religious preeminence of Nippur, became the norm and standard throughout the Euphrates Valley, so that when Marduk and Babylon came practically to replace Enlil and Nippur, the formulas and appeals were transferred to the solar deity of Babylon, who representing more particularly the sun-god of spring, was well adapted to be viewed as the one to bring blessing and favours after the sorrows and tribulations of the stormy season, which had bowed the country low.

Just as the lamentation ritual of Nippur became the model to be followed elsewhere, so at Eridu, the seat of the cult of Ea, the water deity, an elaborate incantation ritual was developed in the course of time, consisting of sacred formulas, accompanied by symbolical rites for the purpose of exorcising the demons that were believed to be the causes of disease and of releasing those who had fallen under the power of sorcerers.[40] The close association between Ea and Marduk (the cult of the latter, as will be subsequently shown,[41] having been transferred from Eridu to Babylon), led to the spread of this incantation ritual to other parts of the Euphrates Valley. It was adopted as part of the Marduk cult and, as a consequence, the share taken by Ea therein was transferred to the god of Babylon. This adoption, again, was not in the form of a violent usurpation by Marduk of functions not belonging to him, but as a transfer willingly made by Ea to Marduk, as his son.

In like manner, myths originally told of Enlil of Nippur, of Anu of Uruk, and of Ea of Eridu, were harmoniously combined, and the part of the hero and conqueror assigned to Marduk. Prominent among these myths was the story of the conquest of the winter storms, pictured as chaos preceding the reign of law and order in the universe. In each of the chief centres the character of creator was attributed to the patron deity, thus in Nippur to Enlil, in Uruk to Anu, and in Eridu to Ea. The deeds of these gods were combined into a tale picturing the steps leading to the gradual establishment of order out of chaos, with Marduk as the one to whom the other gods entrusted the difficult task. Marduk is celebrated as the victor over Tiamat—a monster symbolising primeval chaos.[42] In celebration of his triumph all the gods assemble in solemn state, and address him by fifty names,—a procedure which in ancient phraseology means the transfer of all the attributes involved in these names. The name is the essence, and each name spells additional power. Anu hails Marduk as “mightiest of the gods,” and, finally, Enlil and Ea step forward and declare that their own names shall henceforth be given to Marduk. “His name,” says Ea, “shall be Ea as mine,” and so once more the power of the son is confirmed by the father.

V

There is only one rival to Marduk in the later periods, and he is Ashur, who, from being the patron deity of the ancient capital of the Assyrian empire, rises to the rank of the chief deity of the warlike Assyrians. It is just about the time of Hammurapi that Assyria begins to loom into prominence. It was at first merely an extension of Babylonia towards the north with a strong admixture of Hittite and also Amoritish elements, and then a more or less dependent province; later its patesis exchanged the more modest title, with its religious implication,[43] for sharru, “king,” and acquired a practically independent position at the beginning of the second millennium before this era. Within a few centuries, the Assyrians became formidable rivals to their southern cousins.

The first result of the rise of Assyria was to limit the further extension of Babylonia. The successors of Hammurapi, partly under the influence of the loftier spirit which he had introduced into the country during the closing years of his reign, partly under the stress of necessity, became promoters of peace. Instead of further territorial expansion we find the growth of commerce, which, however, did not hinder Babylonia itself from becoming a prey to a conquering nation that came (as did the Sumerians) from the mountainous regions on the east. Native rulers are replaced by Cassites who, as we have already indicated, retain control of the Euphrates Valley for more than half a millennium. It is significant of the strength which Assyria had meanwhile acquired, that it held the Cassites in check. Alliances between Assyrians and Cassites alternated with conflicts in which, on the whole, the Assyrians gained a steady advantage. But the Assyrian empire also had its varying fortunes before it assumed, in the 12th century, a position of decided superiority over the south. The chief adversaries of the Assyarian rulers were the Hittite groups, who continued to maintain a strong kingdom in north-western Mesopotamia. In addition, there were other groups farther north in the mountain recesses of Asia Minor, which from time to time made serious inroads on Assyria, abetted no doubt by the Hittites or by the Mitanni elements in Assyria, which had probably not been entirely absorbed as yet by the Semitic Assyrians.

As a counterpart to Sargon in the south, we have Tiglathpileser I. in the north (ca. 1130-1100 B.C.). He succeeded in quelling the opposition of the Hittites, carried his triumphant arms to the Mediterranean coast, entered into relations with Egypt, as some of the Cassite rulers had done centuries before, and for a time held in check Babylonia, now again ruled by native kings. Like Sargon’s conquests, the glory of the new empire of Tiglath-Pileser was of short duration. Even before his death there were indications of threatened trouble. For about two centuries Assyria was partially eclipsed, after which the kings of Assyria, supported by large standing armies,[44] bear, without interruption till the fall of Nineveh in 606 B.C., the proud title of “King of Universal Rule,” which, as we have seen,[45] took the place of the Babylonian “King of the Four Regions.” Though “Aramaean” hordes (perhaps identical with Amorites, or a special branch of the latter) continue to give Assyrian rulers, from time to time, considerable trouble, they are, however, held in check until in the reign of Ashumasirpal (884-860 B.C.) their power is effectually broken. This energetic ruler and his successors push on to the north and north-west into the indefinite district known as Nairi, as well as to the west and south-west. Once more the Mediterranean coast is reached, and at a pass on the Nahr-el-Kelb (the “Dog” river) outside of Beirut, Ashurnasirpal and his son Shalmaneser II. (860-824 B.C.) set up images of themselves with records of their achievements.[46]

We are reaching the period when Assyria begins to interfere with the internal affairs of the Hebrew kingdoms in Palestine. Another century, and the northern kingdom (722 B.C.) falls a prey to Assyria’s insatiable greed of empire. Babylonia, reduced to playing the ignoble part of fomenting trouble for Assyria, succeeds in keeping Assyrian armies well occupied, and so wards off the time of her own humiliation. Compelled to acknowledge the superiority of her northern rival in various ways, Babylonia exhausts the patience of Assyrian rulers, to whose credit it must be said that they endeavoured to make their yoke as light as was consistent with their dignity. The consideration that rulers like Sargon of Assyria (721-705 B.C.) showed for the time-honoured prestige of the south was repaid by frequent attempts to throw off the hated yoke, light though it was.

Sennacherib (705-681 B.C.) determines upon a more aggressive policy, and at last in 689 B.C., Babylon is taken and mercilessly destroyed. Sennacherib boasts of the thoroughness with which he carried out the work of destruction. He pillaged the city of its treasures. He besieged and captured all the larger cities of the south—Sippar, Uruk, Cuthah, Kish, and Nippur—and when, a few years later, the south organised another revolt, the king, to show his power, put Babylon under water, and thus obliterated almost all vestiges of the past. The excavations at Babylon[47] carried on by the German expedition show how truthfully Sennacherib described his work of destruction; few traces of the older Babylon have been revealed by the spade of the explorer. What is found dates chiefly from the time of the Neo-Babylonian dynasty, and particularly from the days of Nebuchadnezzar, who, as the restorer of the past glory of the capital, is justified in boasting, as in the Book of Daniel, “Is not this great Babylon that I have built!”[48] Babylonia, however, had the satisfaction of surviving Assyria. By a combination of hordes from the north with Medes of the south-east,—the latter abetted no doubt by Babylonia,—Nineveh is taken in 606 B.C., and the haughty Assyrian power is crushed for ever.

Shortly before the end, however, Assyria witnessed the most brilliant reign in her history—that of Ashurbanapal (668-626 B.C.)—the Sardanapalus of Greek tradition—who was destined to realise the dreams of his predecessors, Sargon, Sennacherib, and Esarhaddon; of whom all four had been fired with the ambition to make Assyria the mistress of the world. Their reigns were spent in carrying on incessant warfare in all directions. During Ashurbanapal’s long reign, Babylonia endured the humiliation of being governed by Assyrian princes. The Hittites no longer dared to organise revolt, Phoenicia and Palestine acknowledged the sway of Assyria, and the lands to the east and northeast were kept in submission. From Susa, the capital of Elam, Ashurbanapal carried back in triumph a statue of Nana,—the Ishtar of Uruk,—which had been captured over 1600 years before, and—greatest triumph of all—the Assyrian standards were planted on the banks of the Nile, though the control of Egypt, as was soon shown, was more nominal than real.

Thus the seed of dominating imperialism, planted by the old Sargon of Agade, had borne fruit. But the spirit of Hammurapi, too, hovered over Assyria. Ashurbanapal was more than a conqueror. Like Hammurapi, he was a promoter of culture and learning. It is to him that we owe practically all that has been preserved of the literature produced in Babylonia. Recognising that the greatness of the south lay in her intellectual prowess, in the civilisation achieved by her and transferred to Assyria, he sent scribes to the archives, gathered in the temple-schools of the south, and had copies made of the extensive collections of omens, oracles, hymns, incantations, medical series, legends, myths, and religious rituals of all kinds that had accumulated in the course of many ages. Only a portion, alas! of the library has been recovered through the excavations of Layard and Rassam (1849-1854) and their successors on the site of Ashurbanapal’s palace at Nineveh in which the great collection was stored.[49]

About 20,000 fragments of clay bricks have found their way to the British Museum, but it is safe to say that this represents less than one half of the extent of the great library which Ashurbanapal had accumulated. His immediate purpose in doing so was to emphasise by an unmistakable act that Assyria had assumed the position of Babylonia, not only as an imperial power and as a stronghold of culture, but also as the great religious centre. The bulk, nay, practically, the whole of the literature of Babylonia was of a religious character, or touched religion and religious beliefs and customs at some point, in accord with the close bond between religion and culture which, we have seen, was so characteristic a feature of the Euphratean civilisation. The old centres of religion and culture, like Nippur, Sippar, Cuthah, Uruk, and Ur, had retained much of their importance, despite the centralising influence of the capital of the Babylonian empire. Hammurapi and his successors had endeavoured, as we have seen, to give to Marduk the attributes of the other great gods, Enlil, Anu, Ea, Shamash, Adad, and Sin, and, to emphasise it, had placed shrines to these gods and others in the great temples of Marduk, and of his close associate, Nebo, in Babylon, and in the neighbouring Borsippa.[50]

Along with this policy went, also, a centralising tendency in the cult and, as a consequence, the rituals, omens, and incantations produced in the older centres were transferred to Babylon and combined with the indigenous features of the Marduk cult.[51] Yet this process of gathering in one place the literary remains of the past had never been fully carried out. It was left for Ashurbanapal to harvest within his palace the silent witnesses to the glory of these older centres. While Babylon and Borsippa constituted the chief sources whence came the copies that he had prepared for the royal library, internal evidence shows that he also gathered the literary treasures of other centres, such as Sippar, Nippur, Uruk. The great bulk of the religious literature in Ashurbanapal’s library represents copies or editions of omen-series, incanta-tion-rituals, myths, legends, and collections of prayers, made for the temple-schools, where the candidates for the various branches of the priesthood received their training. Hence we find supplemental to the literature proper, the pedagogical apparatus of those days—lists of signs, grammatical exercises; analyses of texts, texts with commentaries, and commentaries on texts, specimen texts, and school extracts, and pupils’ exercises.

The temple school appears to have been the depository in each centre of the religious texts that served a purely practical purpose, as handbooks and guides in the cult. Purely literary collections were not made in the south, not even in the temples of Babylon and Borsippa, in which the more comprehensive character of the religious texts was merely a consequence of the centralising tendency in the cult, and, therefore, likewise prompted by purely practical motives and needs. There are no temple libraries in any proper sense of the word, either in Babylonia or in Assyria. Ashurbanapal is the first genuine collector of the literature of the past, and it is significant that he places the library which he gathered, in his palace and not in a temple. Had there been temple libraries in the south, he would undoubtedly have placed the royal library in the chief temple of Ashur—as his homage to the patron deity of Assyria and the protector of her armies.

At the same time, by transferring the literature of all the important religious centres of the south to his royal residence in Nineveh, Ashurbanapal clearly intended to give an unmistakable indication of his desire to make Nineveh the intellectual and religious as well as the political capital. His dream was not that of the Hebrew prophets who hoped for the day when from Zion would proceed the law and light for the entire world, when all nations would come to Jerusalem to pay homage to Jahweh, but his ambition partook somewhat of this character, limited only by his narrower religious horizon which shut him in. For Ashurbanapal, Nineveh was to be a gathering place of all the gods and goddesses of the world grouped around Ashur, just as courtiers surround a monarch whose sway all acknowledge. To gather in his capital the texts that had grown up around the homage paid in the past to these gods and goddesses in their respective centres, was his method of giving expression to his hope of centralising the worship of these deities around the great figure of Ashur. Ashur-banapal’s policy, thus, illustrates again the continued strength of the bond between culture and religion, despite the fact that in its external form the bond appeared political rather than intellectual.

The king’s ambition, however, had its idealistic side which must not be overlooked. The god Ashur was in some respects well adapted to become the emblem of centralised divine power, as well as of political centralisation. The symbol of the god was not, as was the case with other deities, an image in human shape, but a disc from which rays or wings proceed, a reminder, to be sure, that Ashur was in his origin a solar deity,[52] yet sufficiently abstract and impersonal to lead men’s thoughts away from the purely naturalistic or animistic conceptions connected with Ashur. This symbol[53] appears above the images of the kings on the monuments which they erected to themselves. It hovers over the pictures of the Assyrian armies on their march against their enemies. It was carried into the battle as a sacred palladium —a symbol of the presence of the gods as an irresistible ally of the royal armies; and the kings never fail to ascribe to the support of Ashur the victories that crowned their efforts.

Professor Sayce[54] has properly emphasised the influence of this imageless worship of the chief deity on the development of religious ideas in Assyria. Dependent as Assyria was to a large extent upon Babylonia for her culture, her art, and her religion, she made at least one important contribution to what she adopted from the south, in giving to Ashur a more spiritual type, as it were, than Enlil, Ninib, Shamash, Nergal, Anu, Ea, Marduk, or Nebo could ever claim. On the other hand, the limitation in the development of this more spiritual conception of divine power is marked by the disfiguring addition, to the winged disc, of the picture of a man with a bow and arrow within the circle.[55] It was the emblem of the military genius of Assyria.

The old solar deity as the protector of the Assyrian armies had become essentially a god of war, and the royal warriors could not resist the temptation to emphasise by a direct appeal to the eyes the perfect accord between the god and his subjects. This despiritualisation of the winged disc no doubt acted as a check on a conceivable growth of Ashur, which might have tended under more favourable circumstances towards a purer monotheistic conception of the divine government of the universe; for in his case the transference of the attributes of all the other great gods was more fully carried out than in the case of Marduk.[56] In his capacity as a solar deity, Ashur absorbs the character of all other localised sun-gods. Myths in which Ninib, Enlil, Ea, and Marduk appear as heroes are remodelled under Assyrian influence and transferred to Ashur. We have traces of an Assyrian myth of creation in which the sphere of creator is given to Ashur.[57]

Ishtar, the great goddess of fertility, the mother-goddess presiding over births, becomes Ashur’s consort. The cult of the other great gods, of Shamash, Ninib, Nergal, Sin, Ea, Marduk, and even Enlil, is maintained in full vigour in the city of Ashur, and in the subsequent capital Nineveh,[58] but these as well as other gods take on, as it were, the colour of Ashur. They give the impression of little Ashurs by the side of the great one, so entirely does the older solar deity, as the guardian of mighty Assyrian armies, and as the embodiment of Assyria’s martial spirit, overshadow all other manifestations of divine power. This aspect of Ashur receives its most perfect expression during the reign of the four rulers—Sargon, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanapal—when Assyrian power reached its highest point. The success of the Assyrian armies, and consequent political aggrandisement served to increase the glory of Ashur, to whose protection and aid everything was ascribed—but it is Ashur the war-god, the warrior with bow and arrow within the solar circle, who gains in prestige thereby, while the spiritual phase of the deity as symbolised by the winged disc sinks into the background.

For all this, culture and religion go hand in hand with political and material growth, and the Eu-phratean civilisation with its Assyrian upper layer reaches its zenith in the reign and achievements of Ashurbanapal. From the remains of his edifices with their pictorial embellishment of elaborate sculptures on the soft limestone slabs that lined the walls of palaces and temples, we can reconstruct the architecture and art of the entire historical period from the remote past to his own days; and through the contents of the library of clay tablets we can trace the unfolding of culture from the days of Sargon, Gudea, and Hammurapi, through the sway of the Cassites, and the later native dynasties down to the time when the leadership passes for ever into the hands of the cruder but more energetic and fearless Assyrians. The figure of Ashurbanapal rises before us as the heir of all the ages—the embodiment of the genius of the Babylonian-Assyrian civilisation, with its strength and its weaknesses, its spiritual force and its materialistic form.

After the death of Ashurbanapal in 626 B.C., the decline sets in and proceeds so rapidly as to suggest that the brilliancy of his reign was merely the last flicker of a flame whose power was spent—an artificial effort to gather the remaining strength in the hopeless endeavour to stimulate the vitality of the empire, exhausted by the incessant wars of the past centuries. Babylonia survived her northern rival for two reasons. Forced by the superior military power of Assyria to a policy of political inaction or of fomenting trouble for Assyria among the nations that were compelled to submit to her control, Babylonia did not engage in expeditions for conquest, which eventually weaken the conqueror more than the conquered. Instead of war, commerce became the main occupation of the inhabitants of the south. Through the spread of its products and wares, its culture, art, and religious influence were extended in all directions. The more substantial character of the southern civilisation, the result of an uninterrupted development for many centuries, and not, as in the case of Assyria, a somewhat artificial albeit successful graft, lent to Babylonia a certain stability, and provided her with a reserve force, which enabled her to withstand the loss of a great share of her political independence. After the fall of Assyria, there came to the fore a district of the Euphrates Valley in the extreme south—known as Chaldea—which had always maintained a certain measure of its independence, even during the period of strongest union among the Euphratean states, and not infrequently had given the rulers of Babylon considerable trouble. T

he Babylonian empire was also shaken by the blow which brought Assyria to the ground. The Assyrian yoke, to be sure, was thrown off; but in the confusion which ensued, a Chaldean general, Nabopolassar, took advantage of it to make himself the political master of the Euphrates Valley.[59] By means of a treaty of alliance with Elam to the east, Nabopolassar maintained himself on the throne for twenty years, and on his death in 604 B.C., his crown descended to his son—the famous Nebuchadnezzar. Having won his spurs as a general during a military expedition against Egypt, which took place before his father’s death, Nebuchadnezzar was seized with the ambition to found a world-wide empire—a dream which had proved fatal to Assyria. Palestine and Syria were conquered by him, and Egypt humbled, but the last years of his reign were devoted chiefly to building up Babylon, Borsippa, and Sippar in the hope of restoring the ancient grandeur of those political and religious centres.

On Babylon his chief efforts were concentrated; the marvellous constructions to which it owes its eminence in tradition and legend were his achievement. It was he who erected the famous “Hanging Gardens,” a series of raised terraces covered with various kinds of foliage, and enumerated among the “Seven Wonders of the World.” A sacred street for processions was built by him leading from the temple of Marduk through the city and across the river to Borsippa— the seat of the cult of Nebo, whose close association with Marduk is symbolised by their relationship of son and father. This street, along which on solemn occasions the gods were carried in procession, was lined with magnificent glazed coloured tiles, the designs on which were lions of almost life size, as the symbol of Marduk.[60] The workmanship belongs to the best era of Euphratean art. The high towers known as Zikkurats,[61] attached to the chief temples at Babylon and Borsippa, were rebuilt by him and carried to a height greater than ever. By erecting and beautifying shrines to all the chief deities within the precincts of Marduk’ś temple, and thus enlarging the sacred area once more to the dimensions of a precinct of the city, he wished to emphasise the commanding position of Marduk in the pantheon. In this way, he gave a final illustration of how indissolubly religious interests were bound up with political aggrandisement.

The impression, so clearly stamped upon the earliest Euphratean civilisation,—the close bond between culture and religion,—thus marks with equal sharpness the last scene in her eventful history. In Nebuchadnezzar’s days, as in those of Sargon and Hammurapi, religion lay at the basis of Babylonia’s intellectual achievements. The priests attached to the service of the gods continued to be the teachers and guides of the people. The system of education that grew up around the temples was maintained till the end of the neo-Babylonian empire, and even for a time survived its fall. The temple-schools as integral parts of the priestly organisation had given rise to such sciences as were then cultivated—astronomy, medicine, and jurisprudence. All were either attached directly to religious beliefs, as medicine to incantations, astronomy to astrology, jurisprudence to divine oracles, or were so harmoniously bound up with the beliefs as almost to obscure the more purely secular aspects of these mental disciplines. The priests continued to be the physicians, judges, and scribes. Medicinal remedies were prescribed with incantations and ritualistic accompaniments. The study of the heavens, despite considerable advance in the knowledge of the movements of the sun, moon, and planets, continued to be cultivated for the purpose of securing, by means of observations, omens that might furnish a clue to the intention and temper of the gods.

On the death of Nebuchadnezzar, in 561 B.C., the decline of the neo-Babylonian empire sets in and proceeds rapidly, as in Assyria the decline began after the death of her grand monargue. Internal dissensions and rivalries among the priests of Babylon and Sippar divided the land. The glory of the Chaldean revival was of short duration, and in the year 539 B.C., Nabonnedos, the last native king of Babylon, was forced to yield to the new power coming from Elam. It was the same old enemy of the Euphrates Valley, only in a new garb, that appeared when Cyrus stood before the gates of Babylon. Nabonnedos gave the weight of his influence to the priestly party of Sippar. In revenge, the priests of Babylon abetted the advance of Cyrus who was hailed by them as the deliverer of Marduk. With scarcely an attempt at resistance, the capital yielded, and Cyrus marched in triumph to the temple of Marduk. The great change had come so nearly imperceptibly that men hardly realised that with Cyrus on the throne of Babylon a new era was ushered in. In the wake of Cyrus came a new force in culture, accompanied by a religious faith that, in contrast to the Baby Ionian-Assyrian polytheism with its elaborate cult and ritual, appeared rationalistic—almost coldly rationalistic. Far more important than the change of government from Chaldean to Persian control of the Euphrates Valley and of its dependencies was the conquest of the old Babylonian religion by Mazdeism or Zoroastrianism, which, though it did not become the official cult, deprived the worship of Marduk, Nebo, Shamash, and the other gods of much of its vitality.

With its assertion of a single great power for good as the monarch of the universe, Zoroastrianism approached closely the system of Hebrew monotheism, as unfolded under the inspiration of the Hebrew prophets. There was only one attribute which the god of Zoroastrianism, known as Ahura-Mazda, did not possess. He was all-wise, all-good, but not allpowerful, or rather not yet all-powerful. Opposing the power of light there was the power of darkness and evil which could only after the lapse of aeons be overcome by Ahura-Mazda. But this personification of evil as a god, Ahriman, was merely the Zoro-astrian form of the solution of a problem which has been a stumbling-block to all advanced and spiritualised religions:—the undeniable existence of evil in the world. The chief power of the universe conceived of as beneficent could not also be the cause of evil. It is the problem that underlies the discussions in the Book of Job, the philosophical author of which could not content himself with the conventional view that evil is in all cases a punishment for sins, since suffering so frequently was inflicted on the innocent, while the guilty escaped. The Book of Job leaves the question open, and intimates that it is an insoluble mystery. Zoroastrianism admits that the good cannot be the cause of the evil, but the aim of the good is to overcome evil and eventually it will be able to do so. The dualism of Zoroastrianism is merely a temporary compromise, and, essentially, it is monotheistic.[62]

Zoroastrianism recognised the reign of inexorable though inscrutable law in the world, and when it began to exercise its influence on Babylonia, the belief in gods acting according to caprice was bound to be seriously affected. So it happened that although the culture of Babylonia and Assyria survived the fall of Nineveh and Babylon, and for many centuries continued to exercise its sway far beyond its natural boundaries, the religion, while formally maintained in the old centres, gradually decayed. The new spiritual force that had entered the country effectually dissolved the long-existing bond between culture and religion. The profound change of spirit brought about through the advent of Zoroastrianism is illustrated by the rise of a genuine science of astronomy, based on the recognition of law in the heavens, in place of astrology, which, in its Babylonian form at least, had a meaning only as long as it was assumed that the gods, personified by the heavenly bodies, stood above law.[63] The era was approaching when the sciences one by one would cut loose from the leading strings of religious beliefs and religious doctrines. When, two centuries later, another wave of culture coming from the Occident swept over the entire Orient, it gave a further impetus to the divorce of culture from religion in the Euphrates Valley. Hellenic culture, brought to Babylonia by Alexander the Great[64] and his successors, meant the definite introduction of scientific thought; and thereby a fatal blow was given to what was left of the foundations of the beliefs that had been current in Babylonia for several millenniums. Traces of the worship of some of the old gods of Babylonia are to be found almost up to the threshold of our era, but it was merely the shell of the once dominant religion that was left. The culture of the country had become thoroughly saturated with Greek elements, and what Zoroastrianism had left of the religion that once reflected the culture of the Euphrates Valley was all but obliterated by the introduction of Greek modes of thought and life, and of Greek views of the universe.

Plates:

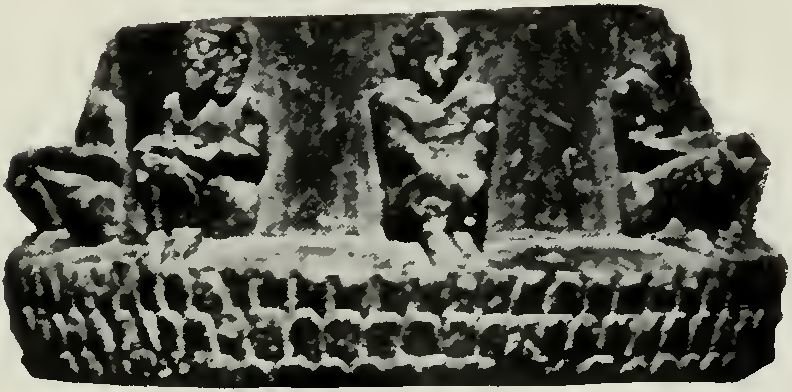

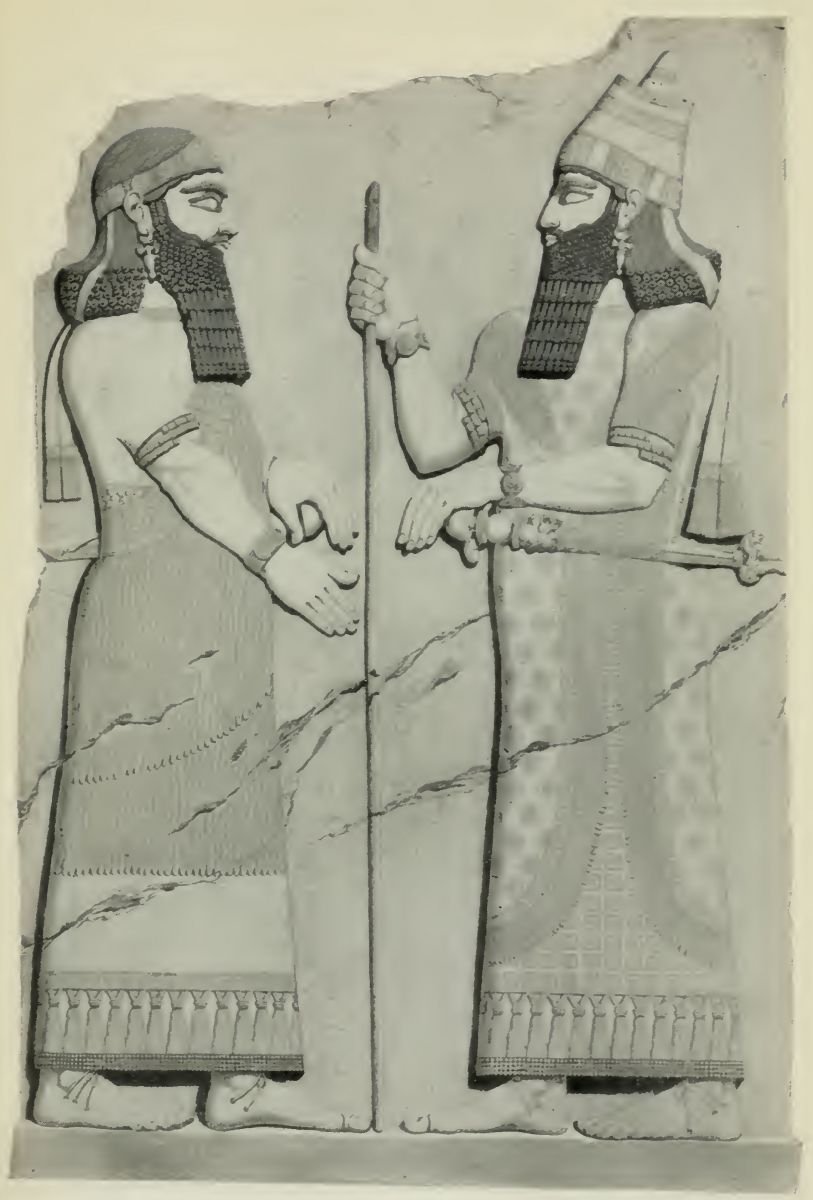

Plate 2:

Pl. 2. Sumerian Types, Ur-Ninâ, Patesi of Lagash (c. 3000 B.C.). and his Family.

Limestone votive tablet found at Telloh and now in the Louvre. See De Sarzec, Decouvertes en Chaldee, Pl. 2 bis, Fig. 1, and pp. 168170; Heuzey, Catalogue des A ntiquites Chaldeetmes, pp. 96-100. Two similar votive tablets of this ruler and his family have been found at Telloh. One of these is also in the Louvre; the other in the Museum at Constantinople. See De Sarzec Decouvertes, Pl. 1 bis, Fig. 2, and Pl. 2 bis, Fig. 1, pp. 171-172. Ur-Ninâ—naked to the waist—is represented in the upper row with a workman’s basket on his head, symbolising his participation in the erection of a sacred edifice. In the accompanying inscription he records his work at the temples of Ningirsu and of Nina and other constructions within the temple area of Lagash. Behind him stands a high official—presumably a priest—with a libation cup in his hand, and before the king are five of his children. The lower row represents the king after the completion of the work pouring a libation. Behind him again the attendant, and before him four other children. The figure with the basket on the head became a common form of a votive offering (see Pl. 29) and persisted to the end of the Assyrian empire as is shown by the steles of King Ashurbanapal and his brother, Shamash-shumukin with such baskets. (See Lehmann, Shamash-shumukin, Leipzig, 1892.)

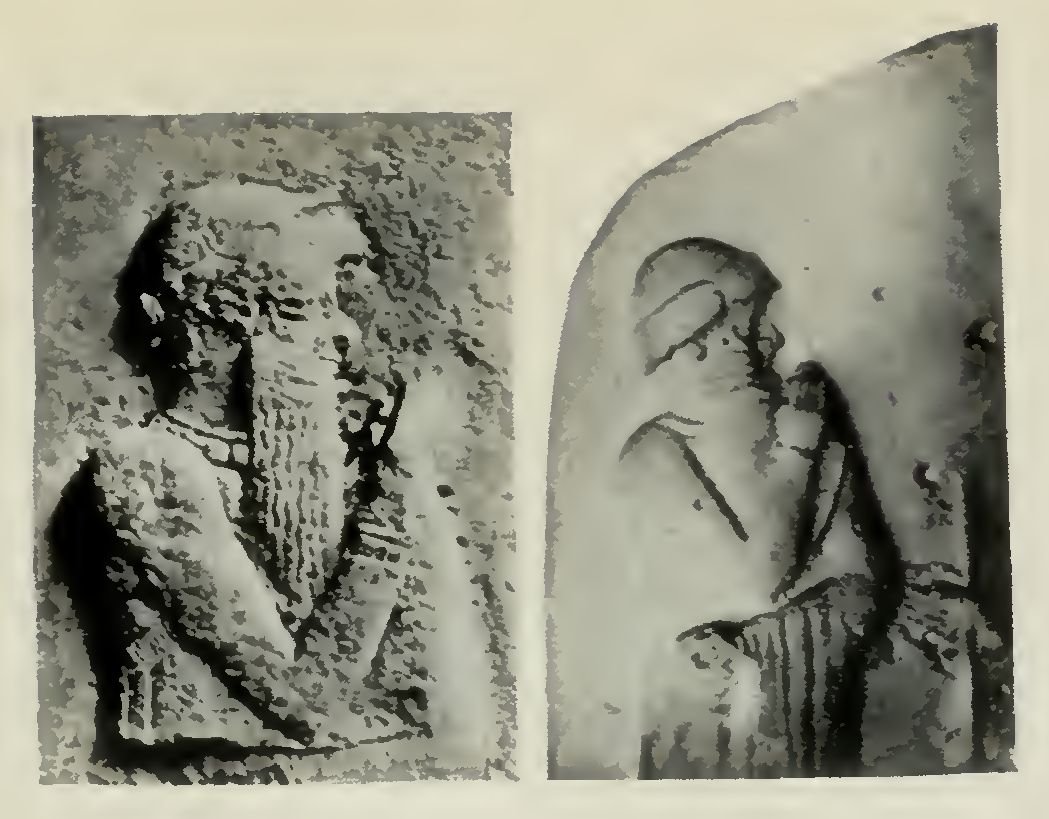

Plate 3:

Pl. 3. Statue of Gudea, Patesi of Lagash (c. 2350 B.C.).

Diorite statue found at Telloh and now in the Louvre. The head was found by De Sarzec in 1881 (De Sarzec Decouvertes, Pl. 12, Fig. 1) and through the discovery of the body in 1903 by Captain Cros, the statue was completed. See Heuzey, “Une Statue complete de Goudea,” in Revue d’Assyriologie, vol. vi., pp. 18-22, and Nouvelles Fouilles de Telloh, pp. 21-25 and Pl. 1. Ten other such diorite statues of Gudea (minus the heads) have been found at Telloh, covered with dedicatory and historical inscriptions. See De Sarzec, Decouvertes, Pis. 9-11; 14; 16-20; and Heuzey, Catalogue pp. 169-188.

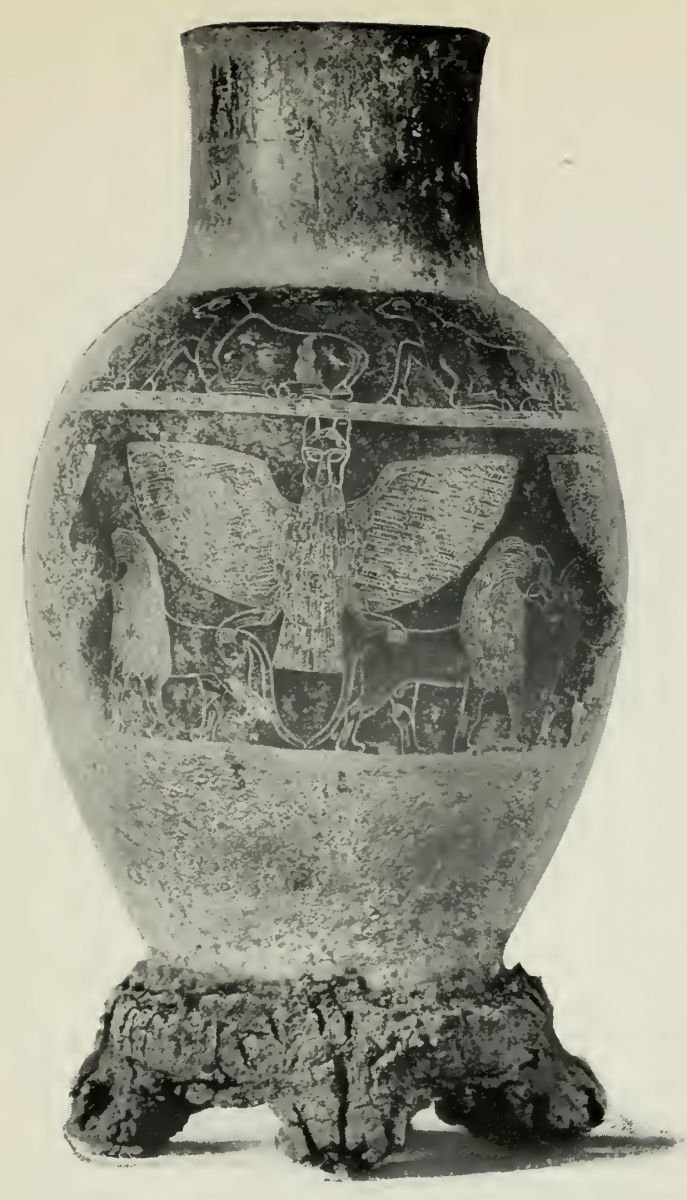

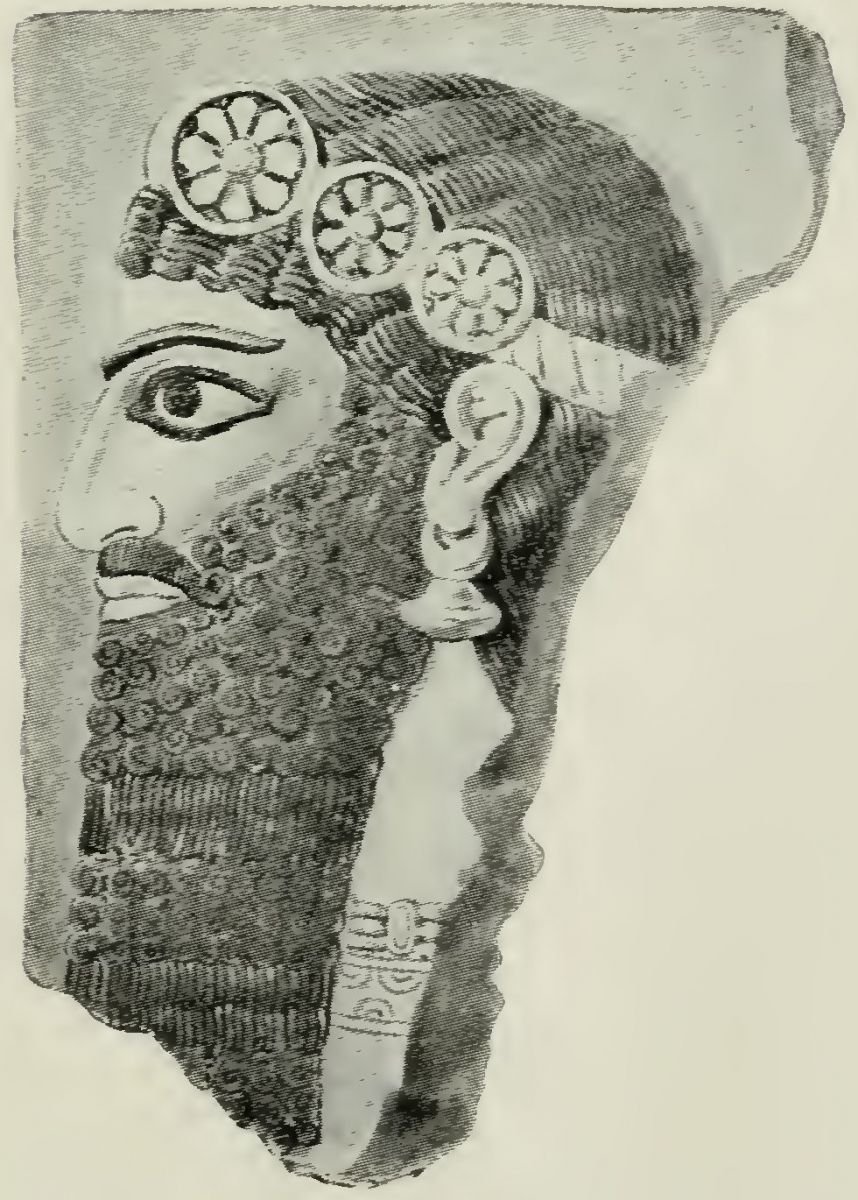

Plate 4:

Pl. 4. Stone Libation Vase of Gudea, Patesi of Lagash (c. 2350 B.C.).