Shishupala-vadha (Study)

by Shila Chakraborty | 2018 | 112,267 words

This page relates ‘Citrakavya (4): Bandhas’ of the study on the Shishupala-vadha (in English) in the light of Manusamhita (law and religious duties) and Arthashastra (science of politics and warfare). The Shishupalavadha is an epic poem (Mahakavya) written by Magha in the 7th century AD. It consists of 1800 Sanskrit verses spread over twenty chapters and narrates the details of the king of the Chedis.

Citrakāvya (4): Bandhas

The nineteenth canto of Śiśupālavadha contains a beautiful description of the battle fought between the yādavas led by Kṛṣṇa and Śiśupāla.

The main content of Śiśupālavadha by Māgha is the assassination of Śiśupāla by Śri-Kṛṣṇa. Throughout this epic the poet exhibits his talent in using variety of figures of speech, metres and at the same time his great potency of luxuriant expression and imagination. One of the characteristic features of Māgha is his using wordtricks or in the other words his power of twisting language. In canto XIX of this epic a number of verses are written in the form of Bandhas like sarvatobhadra, cakra, gomutrikā, murajabandha, ardhabhramaka etc. Bandha is a kind of citra kāvya.

In this verses even if the syllables arranged in different orders they come up with the same sentence and at the same time different orders of arrangements can to different shapes.

Following bandhas are the example of śabdacitra.

Sarvatobhadra

According to Daṇḍin sarvatobhadra is—

‘tadiṣṭa sarvatobhadraṃ bhramanaṃ yadi sarvataḥ’ 3.80 ||[1]

In description it is said—

catuṣṣaṭikoṣṭātmakerasmin bandhe—krameṇādya paṃkticatuṣṭaye pādacatuṣṭayaṃ lekhyam | anantaraṃ cādhaḥsthapaṃ kricatuṣṭaye caturtha—tṛtīya—dvitīya—prathamapādā lekhyāḥ | tatrārdhabhrame adhaḥstha paṃkti catuṣṭaye parāvṛttyā sarvatobhadre parāvṛttyā samāvṛttyā vā caturthādipādalikhanamiti viśeṣaḥ |

In fact there are 64 squares in 8 lines as there are 8 squares in such bandha.

A letter is placed in every square. If last four letters of every eight lines are arranged in opposite direction also, the same sound effect will be created expressing the same significance. It is called sarvatobhadra.

As for example—[19. 27[2] ]

| sa | kā | ra | nā | nā | ra | kā | sa |

| kā | ya | sā | da | da | sā | ya | kā |

| ra | sā | ha | vā | vā | ha | sā | ra |

| nā | da | vā | da | da | vā | da | nā |

| nā | da | vā | da | da | vā | da | nā |

| ra | sā | ha | vā | vā | ha | sā | ra |

| kā | ya | sā | da | da | sā | ya | kā |

| sa | kā | ra | nā | nā | ra | kā | sa |

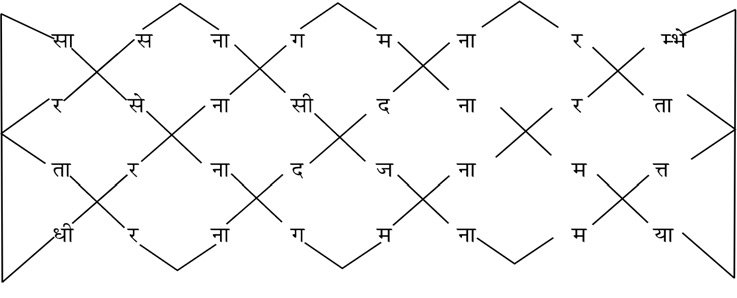

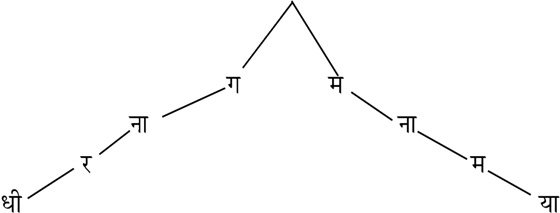

Murajabandha

Murajabandha is—

“atra pādacatuṣke'pi kramaśaḥ parilikhite |

ślokapādakramena syād rekhāsu murajatrayī ||” 2.127 ||[3]

The lines of series of lines took the shape of mṛdanga (an egg shaped drum) as the letters of four lines are arranged serially—

[19.29 ||[4] ]

The arrangements of words found in the first line can also be had if the four lines are read out in the following order—

Similarly the words of the second line can also be had if the first two lines are readout in the following way.

Here we start to read with the first letter of the second line similarly the words of the third line can also be had if the last two lines are readout in the following direction.

Here we start reading from the first letter of the third line. The fourth line can also be arranged if the four lines are readout in the following direction.

Here we start reading from the first letter of the fourth line.

First and fourth and second and third arrangements, if combined together would give out a shape of Muraja, a kind of drum.

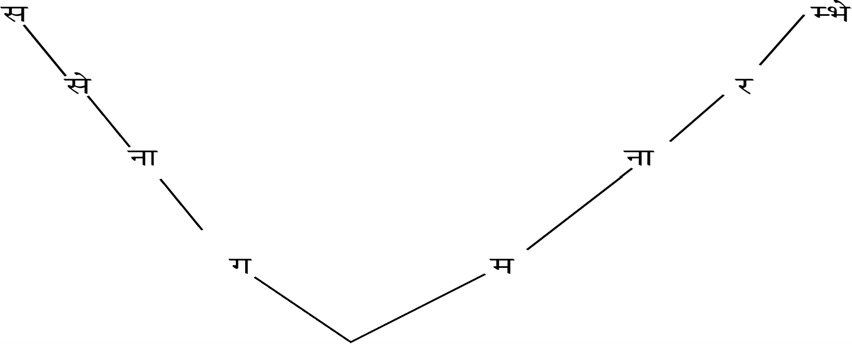

Gomutrikāvanha

There are 32 cells in two rows. There are 16 letteres in every cells, the letters are written in every cell one by one. If we read it diagonally the meaning is understandable. It is called Gomutrikāvanha.

| pra | bṛ | tte | vi | kasad | dhvā | naṃ | sā | dha | ne | pya | vi | ṣā | di | bhiḥ |

| va | bṛ | ṣe | vi | kasa | ddā | naṃ | yū | dha | mā | pya | vi | ṣā | ni | bhiḥ |

[||19. 46 ||[5] ]

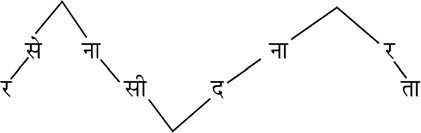

Ardhabhramaka

It is partly like sarvatobhadra.

Here only the half lines are repeated place of full line when read out perpendicularly.

prāhurardhabhramaṃ nāma ślokārdhabhramanaṃ yadi | 3. 80 ||[6]

For this reason it is descriped in the following way This type of bandha is observed in the following verse—

| a | bhī | ka | ma | ti | ke | ne | ddhe |

| bhī | tā | na | nda | sya | nā | śa | ne |

| ka | na | tsa | kā | ma | se | nā | ke |

| ma | nda | kā | ma | ka | ma | sya | ti |

[19.72 ||[7] ]

The half part of the first line can observed if we read it downwards starting from the first syllable. Similarly the first part of the second line can be recreated if we read the words downwords starting from the second syllable and so on.

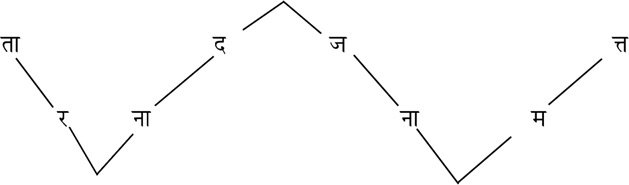

Cakrabandha

Here a concentric circle with three diameters are drawn. All the words are entired in the first three lines. In this way the fourth line is entired in side the outer circle with the last letter of the third line. The renth letter is placed at the centre-It is called cakrabandha.

The verse is as follows—

sattaṃ mānaviśiṣṭamā jirabhasādālamvya bhavyaḥ puro

labdhāghakṣaya śuddhiruddhuratara śrīvatasabhūmirmudā

muktā kāmamapāstabhīḥ para mṛgavyādhaḥ sa nādaṃ hare— 19. 120 ||[8]

rekaughaiḥ samakālamabhramudayī ropaistadātastare |

The verse is reproduced below in the above mentioned way—

Māgha used some verse which are the example of artha citra. These are the eighteenth and fortieth verses of the fourteenth canto. They have double meaning of a word or verse.

Some verses which have triple meaning of a word named arthatrayavācī arthacitra.

In the one hundred and sixteenth verse of the nineteenth canto the meanings of the word “Hari” are Śrī-Kṛṣṇa, Sūrya and India.

sadāmadavalaprāyaḥ samuddhṛtaraso vabhau |

pratītavikramaḥ śrīmān harirharirivāparaḥ || 19. 116 ||[9]

Actually Māgha followed his predecessor Bhāravi in every respect So the using of bandhas in the Śiśupālavadha is not unexpected as it is known to all that Bhāravi also showed his skill in writing verses in various shapes or bandhas. It is interesting to note that in alexandraian age there were some Latin Roman poets who made such jugglery of words in their writing.

The verses of Sotadea can be read backwars also. There was a poet Simmius who made poems in the form of an axe or a nightangle’s eggs.

Dosiadas, another poet showed his skill by making his poem like an alter. So, Bhāravi and Māgha are not only poet in the world making such word tricks. But it should be admitted at the same time that these verses are alright so far as the exercise of brain is concerned, but it is a matter of great doubt whether these verses could contain any kind of poetical merit at all. However, the talent of the poets in arranging the Bandhas can not be denied.

So we may say that Māgha had excellence about various subjects. According to many scholars Māgha was an expert in numerous śāstras (scriptures). He had artistry. Many have discussed the epic of Māgha as the best source of scriptural knowledge. In this context Gobindagopal Mukhopadhaya said—That the poet was expert in many subjects and versatile are realised from differenrt comparisions. Subjects such as grammar, music, ideology etc. are scattered here and there in his epic.

So, to assimilate his epic properly one must have enough knowledge in these subjects. Means, his epic was created only for knowledgeable people. For this a little bit artificialness can be seen evey where in his epic. He consciously tried to show his excellence, which made his epic impure. In spite of these many artificialness, it can be said that Māgha was successful as a poet because, whatever may be less in his epic, there is no scarcity of sentiments.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Jamina Pathak: Kāvyādarśa, p. 528.

[4]:

Haridasa Siddhantavagisha: Op. cit., p. 790.

[5]:

ibid., p. 799.

[7]:

Haridasa Siddhantavagisha: Op. cit., p. 810

[8]:

ibid., p. 831.

[9]:

ibid., p. 829.