Satapatha-brahmana

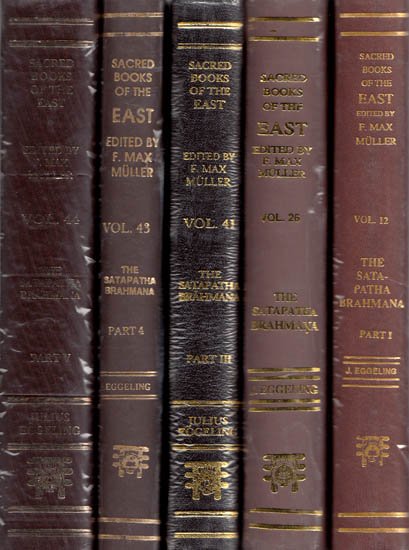

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

This is Satapatha Brahmana I.1.2 English translation of the Sanskrit text, including a glossary of technical terms. This book defines instructions on Vedic rituals and explains the legends behind them. The four Vedas are the highest authortity of the Hindu lifestyle revolving around four castes (viz., Brahmana, Ksatriya, Vaishya and Shudra). Satapatha (also, Śatapatha, shatapatha) translates to “hundred paths”. This page contains the text of the 2nd brahmana of kanda I, adhyaya 1.

Kanda I, adhyaya 1, brahmana 2

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

1. Thereupon he takes the winnowing basket and the Agnihotra ladle[1], with the text (Vāj. S. I, 6 b): 'For the work (I take) you, for pervasion (or accomplishment) you two!' For the sacrifice is a work: hence, in saying 'for the work you two,' he says, 'for the sacrifice.' And 'for pervasion you two,' he says, because he, as it were, pervades (goes through, accomplishes) the sacrifice.

2. He then restrains his speech; for (restrained) speech means undisturbed sacrifice; so that (in so doing) he thinks: 'May I accomplish the sacrifice!' He now heats (the two objects on the Gārhapatya), with the formula (Vāj. S. I, 7 a): 'Scorched is the Rakṣas, scorched are the enemies!' or (Vāj. S. I, 7 b): 'Burnt out is the Rakṣas, burnt out are the enemies!'

3. For the gods, when they were performing the sacrifice, were afraid of a disturbance on the part of the Asuras and Rakṣas: hence by this means he expels from here, at the very opening[2] of the sacrifice, the evil spirits, the Rakṣas.

4. He now steps forward (to the cart[3]), with the text (Vāj. S. I, 7 c): 'I move along the wide aërial realm.' For the Rakṣas roams about in the air, rootless and unfettered in both directions (below and above); and in order that this man (the Adhvaryu) may move about the air, rootless and unfettered in both directions, he by this very prayer renders the atmosphere free from danger and evil spirits.

5. It is from the cart that he should take (the rice required for the sacrifice). For at first the cart (is the receptacle of the rice) and afterwards this hall and because he thinks 'what was at first (in the cart, and hence still unimpaired by entering the householder's abode), that I will operate upon;' for that reason let him take (rice) from the cart.

6. Moreover, the cart represents an abundance; for the cart does indeed represent an abundance: hence, when there is much of anything, people say that there are 'cart-loads' of it. Thus he thereby approaches an abundance, and for this reason he should take from the cart.

7. The cart further is (one of the means of) the sacrifice; for the cart is indeed (one of the means of) sacrifice. To the cart, therefore, refer the (following) Yajus-texts, and not to a store-room, nor to a jar. The Ṛṣis, it is true, once took (the rice) from a leathern bag, and hence, in the case of the Ṛṣis, the Yajus-texts applied to a leathern bag. Here, however, they are taken in their natural application. Because he thinks 'from (or, by means of) the sacrifice I will perform the sacrifice,' let him, therefore, take (rice) from the cart.

8. Some do indeed take it from a (wooden) jar. In that case also he should mutter the Yajus-texts without omitting any; and let him in that case take (the rice) after inserting the wooden sword[4] under (the jar). He does so, thinking 'where we want to yoke, there we unyoke;' for from the same place where they yoke, they also unyoke.

9. (Like) fire, verily, is the yoke of that very cart; for the yoke is indeed (like) fire: hence the shoulder of those (oxen) that draw this (cart) becomes as if burnt by fire. The middle part of the pole behind the prop represents, as it were, its (the cart's) altar[5]; and the enclosed space of the cart (which contains the rice) constitutes its havirdhānam (receptacle of the sacrificial food)[6].

10. He now touches the yoke, with the text (Vāj. S. I, 8 a): 'Thou art the yoke (dhur); injure (dhūrv) thou the injurer! injure him that injures us! injure him whom we injure!' For there being a fire in the yoke by which he will have to pass when he fetches the material for the oblation, he thereby propitiates it, and thus that fire in the yoke does not injure him when he passes by.

11. Here now Āruṇi said: 'Every half-moon[7] I destroy the enemies.' This he said with reference to this point.

12. Thereupon, whilst touching the pole behind the prop, he mutters (Vāj. S. I, 8 b-9 a): 'To the gods thou belongest, thou the best carrying one, the most firmly joined[8], the most richly filled[9], the most agreeable (to the gods), the best caller of the gods!' 'Thou art unbent, the receptacle of oblations; be thou firm, waver not!' Thus he eulogises the cart, hoping that he may obtain the oblation from the one thus eulogised and pleased. He adds (Vāj. S. I, 9 b), 'May thy Lord of Sacrifice not waver!' for Lord of Sacrifice is the sacrificer, and it is for the sacrificer, therefore, that he thus prays for firmness.

13. He now ascends (the cart by the southern wheel), with the text (Vāj. S. I, 9 c): 'May Viṣṇu ascend thee!' For Viṣṇu is the sacrifice; by striding (vi-kram) he obtained for the gods this all-pervading power (vikrānti) which now belongs to them. By his first step he gained this very (earth), by the second the aërial expanse, and by the last step the sky. And this very same pervading power Viṣṇu, as sacrifice, by his strides obtains for him (the sacrificer).

14. He then looks (at the rice) and (addressing the cart) mutters (Vāj. S. I, 9 d): 'Wide open (be thou) to the wind!' For wind means breath; so that by this prayer he effects free scope for the air of the (sacrificer's) breath.

15. With the text (Vāj. S. I, 9 e), 'Repelled is the Rakṣas!' he then throws away whatever (grass, &c.) may have fallen on it. But if nothing (have fallen on it), let him merely touch it. He thereby drives away from it the evil spirits, the Rakṣas.

16. He touches (the rice), with the text (Vā, . S. I, 9 f), 'Let the five take!' for five are these fingers, and fivefold also is the sacrifice[10]; so that he thereby puts the sacrifice on it (the cart).

17. He then takes (the rice), with the text (Vāj. S. I, 10 a, b): 'At the impulse (prasavana) of the divine Savitṛ, I take thee with the arms of the Aśvins, with the hands of Pūṣan, thee, agreeable to Agni!' For Savitṛ is the impeller (prasavitṛ) of the gods: therefore he takes this as one impelled by Savitṛ. 'With the arms of the Aśvins,' he says, because the two Aśvins are the Adhvaryu priests (of the gods). 'With the hands of Pūṣan,' he says, because Pūṣan is distributer of portions (to the gods), who with his own hands places the food before them. The gods are the truth, and men are the untruth: thus he thereby takes (the rice) by means of the truth.

18. He now announces (the oblation) to the deity (for whom it is intended). For when the Adhvaryu is about to take the oblation, all the gods draw near to him, thinking, 'My name he will choose! my name he will choose!' and among them who are thus gathered together, he thereby[11] establishes concord.

19. Another reason for which he announces (the oblation) to the deity, is this: whichever deities are chosen, they consider it as an obligation that they are bound to fulfil whatever wish he entertains whilst taking (the oblation); and for that reason also he announces it to the deity. After taking the oblations (to the other deities) in the same way as before[12],--

20. He touches (the rice that is left), with the text (Vāj. S. I, 11 a): 'For existence (or, abundance,--I leave) thee, not for non-offering[13]!' He thereby causes it to increase again.

21. He now (whilst seated on the cart) looks towards east, with the text (Vāj. S. I, 11 b): 'May I perceive the light!' For that cart being covered up, its eye is thereby, as it were, affected with evil. Light, moreover, represents the sacrifice, the day, the gods, and the sun; so that he thereby perceives this same (fourfold) light.

22. He then descends (from the cart), with the text (Vāj. S. I, 11 c): 'May those provided with doors stand firm on the earth!' Those provided with doors are the houses: for the houses of the sacrificer might indeed be capable of breaking down behind the back of his Adhvaryu, when he walks forward (from the cart) with the sacrifice, and might crush his (the sacrificer's) family. By this (text), however, he causes them to stand firmly on this earth, so that they do not break down and crush (his family); for this reason he says: 'May those provided with doors stand firm on the earth!' He then walks forward (north of the Gārhapatya fire), with the text (Vāj. S. I, 11 d), 'I move along the wide aërial realm;' the application of which is the same (as before; see par. 4).

23. In the case of one (viz. householder) whose Gārhapatya fire they (the priests) use for coking oblations, they place the utensils in the Gārhapatya (house); and let him (the Adhvaryu) in that case put (the winnowing basket with the rice) down at the back (or west) side of the Gārhapatya. But in the case of one whose Āhavanīya they use for cooking oblations, they place the utensils together in the Āhavanīya; and let him in that case put it (the rice) down at the back of the Āhavanīya. He should (in either case) do so, with the text (Vāj. S. I, 11 e), 'On the navel of the earth I place thee!' for the navel means the centre, and the centre is safe from danger: for this reason he says, 'On the navel of the earth I place thee!' And further, 'In the lap of Aditi (the boundless or inviolable earth)!' for when people guard anything very carefully, they commonly say that 'they, as it were, carried it in their lap;' and this is the reason why he says, 'In the lap of Aditi!' And further, 'O Agni, do thou protect this offering!' whereby he makes this oblation over for protection both to Agni and to this earth: for this reason he says, 'O Agni, do thou protect this offering!'

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

For the Agnihotra-havaṇī or ladle used for making the morning and evening milk-oblations, see note on I, 3, 1, 1. For the winnowing basket (śūrpa), see I, 1, 4, 19 seq.

[2]:

Literally, 'from the very mouth,' which refers both to the mouth or hollow part of the two vessels (from which the enemies are, as it were, burnt out), and to the opening of the sacrifice. The same symbolical explanation is met with on the occasion of the heating of the sacrificial spoon, I, 3, 1, 5.

[3]:

The cart containing the rice or barley, or whatever material may be used instead, stands behind (i.e. west of) the Gārhapatya, fitted with all its appliances (except the oxen). Kāty. Śr. II, 3, 12. Rice-grains, as the most common material, will be assumed to constitute the chief havis (sacrificial food) at the present sacrifice.

[4]:

The sphya is a straight sword (khaḍga) or knife, a cubit long, carved out of khadira wood (Mimosa Catechu). Kāty. Śr. I, 3, 33; 39. It is used for various purposes calculated to symbolically insure the safe and undisturbed performance of the sacrifice. On the present occasion it represents the yoke, by touching which (par. 10) the cart is connected with the sacrifice. At the close of the sacrifice also the offering spoons are, as it were, unyoked (or relieved of their duties), by being placed on the yoke, if the rice was taken from the cart; or on the wooden sword lying on the jar, if it was taken from the latter. See I, 8, 3, 26.

[5]:

The pole of an Indian cart consists of two pieces of wood, joined together in its forepart and diverging towards the axle. Hence, as Sāyaṇa remarks, it resembles the altar in shape, being narrower in front and broader at the back, the altar measuring twenty-four cubits in front and thirty cubits at the back. At the extreme end of the pole a piece of wood is fastened on, or the pole itself is turned downwards, so as to serve as a prop or rest (popularly called 'sipoy' in Western India, and 'horse' in English).

[6]:

The havirdhāna (-maṇḍapa) is a temporary shed or tent erected on the sacrificial ground for the performance of the Soma-sacrifice, in which the two carts containing the Soma-plants are placed. These carts themselves, however, are also called havirdhāna. Cf. IV, 6, 9, 10 seq.; III, 5, 3, 7.

[7]:

I.e. at the time of the new and the full moon. Schol.

[8]:

Sasni-tama (? 'the most bountiful'); sasni is explained by Mahīdhara (in accordance with Yāska, Nir. V, 1) by saṃsnāta, from snā, 'to purify, cleanse,' or from snā (snai), 'to envelop, wrap round;' hence 'cleanest or purest,' or 'most firmly secured by being tied (with thongs, &c.)' The latter was probably the meaning connected with the word in this sacrificial formula; though the correct derivation is no doubt from san, 'to acquire, gain,' and 'to bestow' (Roth, Nirukta notes, p. 52). In modern Indian carts the yoke is fastened on to the pole by a string.

[9]:

Papritama, 'most filled with rice,' &c. Schol.

[10]:

According to Sāyaṇa, because there are five kinds of oblations (havish-paṅkti) at the Soma-sacrifice. Cf. Ait. Br. II, 24, with Haug's translation. Compare also the distinction of five different parts-in the victim at animal sacrifices: Śat. Br. I, 5, 2, 16; Ait. Br. II, 14; III, 23; and the five kinds of victims, viz. man, horse, bullock, ram, and he-goat: Ath. V. XI, 2, 9; Śat. Br. I, 2, 3, 6. 7; VI, 2, 1, 6. 18; VII, 5, 2, in; Taitt. S. IV, 2, 10; Chānd. Up. II, 6, 1.

[11]:

Viz. by calling out the names, since, without this being done, quarrels would arise among the deities as to whom the offering might be intended for. Mahīdh.

[12]:

Viz. as in the case of the oblation to Agni, and substituting the name of the respective deity in the formula used above (par. 17), 'Thee, agreeable to (Agni)!' The oblations prescribed for the full-moon sacrifice are a cake on eight potsherds for Agni, and one on eleven potsherds for Agni and Soma: for each of these cakes he takes four handfuls from the cart [and throws them into the Agnihotra ladle lying on the winnowing basket which he holds with his left hand. With each of the first three handfuls of each of the two oblations he repeats the above text, whilst the fourth handful is thrown in silently. After the oblation for Agni is taken, he pours it from the ladle into the winnowing basket so as to lie on the southern side; and then takes out the oblation for Agni-Soma, which is afterwards poured into the basket so as to lie north of the first heap]. Kāty. Śr. II, 3, 20-21 and Scholl.

[13]:

Thus Mahīdhara (i.e. to serve for future oblations, or as food for the priests'). Perhaps the meaning is, 'For a (divine or human) being thee, not for the evil spirit!' Cf. St. Petersburg Dict. s.v. bhūta.