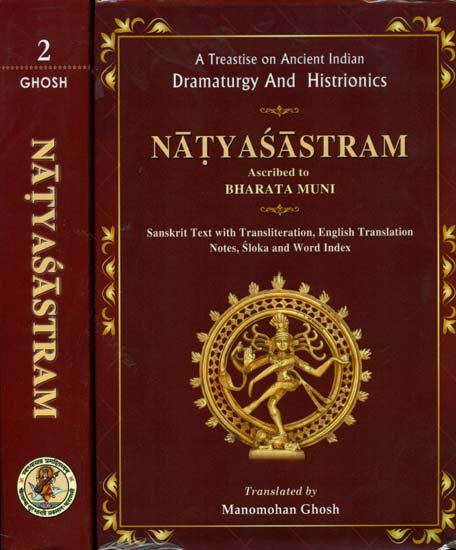

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Chapter XXXIV - Types of Characters (prakṛti)

1. I shall next speak of the salient features of characters, and of all the four kinds of Heroes in their essential aspect.

Three Types of Character in a Play

2-3. Characters male and female [in a play], are in general of three types: superior, middling and inferior.

A Superior Male Character

3-4. [A man] who has controlled his senses, is wise, skilled[1] in various arts and crafts (śilpa), honest, expert in enjoyment,[2] brings consolation to the poor, is versed in different Śāstras, grave, liberal, patient and munificent, is to be known as a ‘superior’ (uttama) [male][3] character.

A Middling Male Character

4-5. [A man] who is an expert in the manners of people, proficient[4] in arts and crafts as well as in Śāstras, has wisdom, sweetness [of manners], is to be known as a ‘middling’ (madhyama) [male] character.

Inferior Male Characters

6-9. [Men] who are harsh in words, ill-mannered, low-spirited, criminally disposed,[5] irascible and violent, can kill friends, can kill anyone by torturing,[6] are prone to engage himself in useless things, speak very little, are mean, haughty in words, ungrateful, indolent, expert in insulting honoured persons, covetous of women, fond of quarrel, treacherous, doers of evil deeds, stealers of others’ properties, are to be known as ‘inferior’ (adhama) [male] characters. These are the three classes of male character according to their nature.

A Superior Female Character

10-12. I shall now speak in due order, of female characters. A woman who has a tender nature, is not fickle, speaks smilingly, is free from cruelty, attentive to words of her superiors, bashful, good-mannered, has natural beauty, nobility and such other qualities, and is grave and patient, is to be known as a ‘superior’ [female] character.

A Middling Female Character

12-13. A woman who does not possess these qualities to a great extent and always, and has some faults mixed with them, is to be known as a ‘middling’ [female] character.

An Inferior Female Character

13-14. An ‘inferior’ female character is to be known in brief from an inferior male character.

A Character of Mixed Nature

14-16. Maid servants and the like are characters of mixed nature. A hermaphrodite is also a mixed character, but of the inferior kind. O the best of Brahmins, the Śakāra[7] and the Viṭa[8] and others [like them] in a drama, are also to be known as characters of mixed nature.

So much about the characters which may be male, female or hermaphrodite.

Four Classes of Hero

17-18. I shall now describe their classes according to their conduct. Among these, Heroes (nāyaka) are known to be of four classes, and they belong to the superior and the middling types and have various characteristics.

18-19. The Hero is described as being of four kinds: the self-controlled and vehement (dhīroddhata), the self-controlled and light-hearted (dhīralalita), the self-controlled and exalted (dhīrodātta) and self-controlled and calm (dhīrapraśānta).

19-21. Gods are self-controlled and vehement, kings are self-controlled and light-hearted, ministers are self-controlled and exalted, and Brahmins and merchants are self-controlled and calm Heroes.

The Four Classes of Jesters

21-22. To these again belong the four classes of Jesters. They are Sannyāsins, Brahmins, other twice-born castes and disciples, in cases respectively of gods, kings, ministers (amātya) and Brahmins.[9]

These should be friends during [the Heroe’s] separation [from the beloved one], and experts in conversation.

The Hero

23. In case of many male characters in a play, one who being in misfortune or distress, ultimately attains elevation, is called the Hero.

24. And when there are more than one of such description, one whose misfortune and elevation are prominent, should be called the Hero.

Four Classes of Heroine

25-27. These [four] are always Heroes in dramatic works (lit. poetical compositions). I shall now speak of Heroines who [also] are of four classes: a goddess, a queen, a woman of high family, and a courtezan. These according to their characteristics, are of various kinds, such as self-controlled (dhīrā), light-hearted (lalitā), exalted (udāttā) and modest (nibhṛtā).

27-28. Goddesses and king’s women possess all these qualities. Women of high family, are exalted and modest, while a courtezan and a crafts-woman may be exalted and light-hearted.

Two Classes of Employment for Characters

29-30. The characters [in a play] have two kinds of of employment: external (bāhya) and internal (ābhayantara). I shall now speak of their characteristics.

[The character] which has dealings with the king, is an internal employee, and one who has dealings with the [people] outside, is an external employee.

Female Inmates of the Harem

31-34. I shall now describe the classes and functions of women[10] who have dealings with the king. They are the chief queen (mahādevī), other queens (devī), other highborn wives (svāminī), ordinary wives (sthāyinī),[11] concubines (bhoginī), crafts-women (śilpakāriṇī), actresses (nāṭakīyā),[12] dancers (nartakī), maids in constant attendance (anucārikā), maids of special work (paricārikā), maids in constant movement (sañcārikā), maids for running errands (preṣaṇa-cārikā), Mahattarīs (matrons), Pratihārīs (ushers) and maidens (kumārī) and Sthavirās (old dames) and Āyuktikās (female overseers).

The Chief Queen

35-37. The chief queen is one who has been consecrated on her head, is of high birth and character, possessed of accomplishments; advanced in age, indifferent [to her rivals]1, free from anger and malice, and who [fully] understands the king’s character, shares equally his joys and sorrows, is always engaged in propitiatory rites for the good of the [royal] husband, and is calm, affectionate, patient, and benevolent to the inmates of the harem

Other Queens

38-39. Those [wives of the king] who have all these qualities except that they are denied proper consecration, and who are proud and of royal descent, are eager for enjoying affection, are pure and always brilliantly dressed, jealous of their rivals,[13] and maddened on account of their young age and [many other] qualities, are called queens (devī).

Other Highborn Wives

40-41. Daughters of generals, or ministers or of other employees when they (i.e. their daughters) are elevated by the king through bestowal of affection and honour, and become his favourite due to good manners and physical charm, and attain importance through their own merits, are known as highborn wives (svāminī).

Ordinary Wives

42-43. Ordinary wives of a king are those who have physical charm and young age, is violent [in sexual acts], full of amorous gestures and movements, expert in the enjoyment of love, jealous of rivals, [always] alert and ready [to act], free from indolence and cruelty, and capable of showing honours to person according to their status.

Concubines

44-45. Concubines of the king are women who are honest (dakṣā) and clear [in their dealings], exalted, always brilliant with their scents and garlands, and who follow the wishes of the king and are always devoid of jealousy, are well-behaved, demand no honour, are gentle [in manners] and not very vain, and are sober, humble, and forbearing.

Crafts-women

46-47. Those women who are conversant with various arts and skilled in different crafts, know different branches of the art of perfume-making, are skilled in different modes of painting, know all about the comfort of beds, seats and vehicles, and are sweet, clever, honest (dakṣā), agreeable (citrā), clear [in their dealings], gentle, and humble, are to be known as crafts-women (śilpa-kārikā).

Actresses

48-51. Women who have physical beauty, good qualities, generosity, feminine charm, patience, and good manners, and who possess soft, sweet and charming voice, and varying notes in her throat, and who are experts in the representation of Passion (helā), and Feeling (bhāva), know well of representation of the Temperament (sattva), have sweetness of manners, are skilled in playing musical instruments, have a knowledge of notes, Tāla and Yati, and are associated with the master [of the] dramatic art, clever, skilled in acting, capable of using reasoning positive and negative (ūhāpoha), and have youthful age with beauty, are known as actresses (nāṭakīyā).[14]

Dancers

51-54. Women who have [beautiful] limbs, are conversant with the sixty-four arts and crafts (kalā), are clever, courteous in behaviour, free from female diseases, always bold, free from indolence, inured to hard work, capable of practising various arts and crafts, skilled in dancing and songs, who excel by their beauty, youthfulness, brilliance and other qualities all other women standing by, are known as female dancers (nartakī).

Maids in Constant Attendance

54-55. Women who do not under any condition leave the king, are maids in constant attendance (anucārikā).

Maids of Special Work

55-57. Those women who are employed for looking after the umbrella, bed, and seat as well as for fanning and massaging him, and applying scent to his body and [assisting him] in his toilet, and his wearing of ornaments, and garlands, are known as maids of special work (paricārikā).[15]

Maids in Constant Move

57-59. Those women who [always] roam about in different parts [of the palace], gardens, temples, pleasure pavillions, and strike the bell indicating the Yāmas,[16] and those who having these characteristics are precluded by the playwrights from [sexual] enjoyment,[17] are called maids in constant move (saṃcārikā).

Errand Girls

59-60. Women who are employed by the king in secret missions connected with his love-affairs, and are often to be sent [in some such work], are to be known as errand-girls (preṣaṇa-cārikā).

Mahattarīs

60-61. Women who, for the protection of the entire harem and for [the king’s] prosperity, take pleasure in singing hymns [to gods], and in performing auspicious ceremonies, are known as Mahattarīs (matrons).

Pratīhārīs

61-62. Women who lay before the king any business related to various affairs [of the state] such as treaty, war and the like, are called Pratihārīs (usher).

Maidens

62-63. Girls who have no experience of love’s enjoyment (rati-saṃbhoga), and are quiet, devoid of rashness, modest, and bashful, are said to be maidens (kumārī).[18]

Old Dames

63-64. Women who know the manners of departed kings, and have been honoured by them, and who know the character of all [the members of the harem] are said to be old dames (vṛddhā).

Āyuktikās

64-66. Women who are in charge of stores, weapons,[19] and fruits, roots and grains, who examine the food [cooked for the king], and are in charge of [lit. thinkers of] scents, ornaments and garlands and clothes [he is to use], and who are employed for various [other] purposes, are called Āyuktīkās (female overseer).[20] These in brief are the different classes women of the [royal] harem.

Other Women Employees in the Harem

67. I shall now speak of the characteristics of the remaining characters who are employed in some duty or special work [in the harem].

68-70. Those who are not rash, restless, covetous and cruel in mind, and are quiet, forgiving, satisfied, and have controlled anger and have conquered the senses, have no passion, are modest and free from female diseases, attached and devoted [to the king] and have come from different parts of the state, and have no womanly infatuation, should be employed in the palace of a king.

Other Inmates of the Harem

70-73. The hermaphrodite who is a character of the third class, should be employed in a royal household for moving about in the harem. And Snātakas,[21] Kañcukīyas,[22] Varṣadharas,[23] Aupasthāyika-nirmuṇḍas,[24] are to be placed in different parts of the harem. Persons who are eunuchs or are devoid of sexual function, should always be made the inmates of the harem in a Nāṭaka.

The Snātaka

73-74. A Snātaka[25] with polished manners, should be made the warden of the gate (dvāstha).[26] Old Brāhmins who are clever and free from sexual of passion, should always be employed by the king for various needs of queens.

The Kañcukīyas etc.

75-78. Those who have learning, truthfulness, are free from sexual passion, and have deep knowledge and wisdom, are known as Kañcukīyas.[27] The king should employ them in business connected with polity. And the Varṣadharas should be employed in errands relating to love-affairs. And the Aupasthāyika-nirmuṇḍas are to be employed in escorting women, and in guarding maidens and girls. In bestowing honour to women the king should employ the maids in constant attendance.

The Nāṭakīyā

78-79. Women in the royal harem who attend all the movements of the king, should be employed, when they are proficient in performing all classes of dance, in the [royal] theatre under the authority of the harem.[28]

The Varṣadharas

79-80. Persons of poor vitality, who are clever and are hermaphrodites and have feminine nature, but have not been defective from birth, are called Varṣadharas.[29]

The Nirmuṇḍas

80-81. Persons who are hermaphrodites, but have no of womanly nature and have no sexual knowledge, are called Nirmuṇḍas.[30]

These are the eighteen kinds of inmates of the [royal] harem described by me.

External Persons

82-83. I shall next speak of persons who move about in public.

They are: the king, the leader of the army (senāpati), the chaplain (purodhas), ministers (mantrin),[31] secretaries (saciva).[32] judges (prāḍvivāka), wardens of princes (kumārādhikṛta)[33] and many other members of the king’s court (sabhāstāra). I shall speak of their classes and characteristics. Please listen about them.

The King

84-88. The king should be intelligent, truthful, master of his senses, clever, and of good character, and he should possess a good memory; and be powerful, high-minded and pure, and he should be far-sighted, greatly energetic, grateful, skilled in using sweet words; he should take a vow of protecting people and be an expert in the methods of [different] work, alert, without carelessness, and be should associate with old people, and be well-versed in the Arthasāstra and the practice of various policies, a promoter of various arts and crafts, and an expert in the science of polity, and should have a liking for this, [Besides these] he should know his actual position, prosperity and its decline, and the weak points of his enemies, and [principles of] Dharma, and be free from evil habits.

The Leader of the Army

89-90. One who possesses a good character and truthfulness, and is always active (lit. has given up idleness), sweet-tongued, knows the rules regarding weakness of the enemy, and proper time for marching against him, has a knowledge of the Arthaśāstra and of everything about wealth, is devoted [to the king], honoured in his own clan, and has a knowledge about time and place, should be made a leader of the army, for these qualities of him.

The Chaplains and Ministers

91. Those who are high-born, intelligent, well-versed in Śruti and polity, fellow-countrymen [of the king], devoted [to him], free from guile (lit. pure) and followers of Dharma, should be chaplains and ministers, for these qualities of them.[34]

Secretaries

92-93. Those who are intelligent, versed in polity, powerful, sweet-tongued, conversant with the Arthasāstra, and attached to the subjects and are followers of Dharma, should be always appointed by kings as secretaires (amātya).[35]

Judges

93-95. Those who know well about litigation, and the true nature of pecuniary transactions, are intelligent, and well-versed in many departments of knowledge, impartial, followers of Dharma, wise, able to discriminate between good and bad deeds, and are forbearing and self-controlled, and can control anger, are not haughty and have similar respect for all, should ba placed in seats of justice as judges (prāḍvivāka).[36]

Wardens of Princes

95-97. Those who are alert, careful, always active (lit. free from indolence), inured to hard work, affectionate, forbearing, disciplined, impartial, skillful, well-versed in polity and in discipline, and who are masters of reasoning positive and negative, have knowledge of all the Śāstras and are not vitiated by passion and such other things, and who are hereditary servants of the king, and are attached to him, should be made wardens of princes,[37] because of their possessing these various qualities.

Courtiers

98. Members of the court (sabhāstāra)[38] should be appointed by practical people according to the views of Brhaspati[39] after taking note of the [various] qualities of these (i.e., ministers etc.).

99. These are the characteristics of various characters, [in a play], that I was to say. I shall next speak of the characteristics of [persons suited to] various roles.

Here ends Chapter XXXIV of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, which treats of the Types of Different Characters.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See note 1 on 4-5 below.

[2]:

The text here is corrupt, The reading bhogadakṣā is suggested on the assumption that a superior male character controlling his senses should not invariably be an ascetic, and he should be disposed to enjoy life legitimately.

[3]:

As female characters have been treated of below, this and the two following passages relate to male characters.

[4]:

If should be noticed that a superior male character should be skilled in various arts and crafts, while a middling male character should be proficient in these. The purpose of this distinction seems to be significant. A superior character should have knowledge of arts and crafts as an accomplishment, while the middling character should be capable of making a professional use of these for earning a livelihood. Saṃvāhaka (Mṛcch. II) who is a middling character, seems to support this view. About his practising massage, he says: Madam, I learnt it as an art. It has now become my profession (ajjae kaleti sikkhidā, ājīviā dāṇim saṃvuttā).

[5]:

Śalyabuddhika.

[6]:

Citraghātaka.

[7]:

See XXXV. 78

[8]:

See XXXV. 77.

[9]:

The text here has been emended with the help of the ND. (168b). See also BhP. (pp. 281-282).

[10]:

This gives us a very good glimpse of the royal harem in ancient India.

[11]:

This passage shows that a king in ancient India, had a large number of wives. According to a Ceylon tradition, the king Bindusāra had sixteen wives. In Svapna. (VI. 9) Udayana refers to his mother-in-law Mahāsena’s chief queen as ṣoḍaśāntaḥpurajyeṣṭhā (being at the head of the sixteen wives).

[12]:

Cf. Pali nāṭakitthī.

[13]:

Bhāsa seems to disregard this rule. For Padmāvatī has no jealousy against Vāsavadattā (see Svapna.).

[14]:

Perhaps for the personal safety of the king, male actors were not admitted in the theatre attached to the royal harem. The Bṛhatkathā-śloka-samgraha (II. 32, ed. Lacôte) testifies to the antiquity of this practice. In the palaces of the king of Cambodia and of some Sultans of Indonesia too, women only are engaged to produce plays. See Santidev Ghosh, Jāvā-O-Bālir Nṛtya-gīt (Bengali) Calcutta, 1952 p. 11.

[15]:

In Vikram. (V. 3. 1.) a Yavanī brings the king his bow. She was indeed a paricārikā. But her Yavana origin is not mentioned in the NŚ.

[16]:

Yāma =one eighth part of the day, three hours.

[17]:

That is, they should not be personally implicated in love-affairs.

[18]:

Ex. Vasulakṣmī (Vasulacchī) in the Mālavi.

[19]:

See above note 1 on 55-57. Kālidāsa seems to ignore this functionary of the harem.

[20]:

Cf. Yuta (= Yukta) in Asoka’s Girnar Rock III. Āyuktikā may be his female counterpart in the royal harem.

[21]:

See below note 1 on 73-74.

[22]:

See below note 1 on 75-78.

[23]:

See below note 1 on 78-80.

[24]:

See below note 1 on 80-81.

[25]:

From later dramas the Snātaka disappears altogether. Was Puṣyamitra described by S. Lévi as ‘a mayor of the palace,’ a Snātaka?

[26]:

According to the AŚ of Kauṭilya, dauvārika was important officer of high rank and not a simple door-keeper of the ordinary menial type. See AŚ. I. 2. 8.

[27]:

See note 1 on XIII. 112-113. Bhāsa has ‘Kāñcukīya.’

[28]:

See above 48-51 and the note on the word nāṭakīyā. It is not clear why the nāṭakīyā has been described over again and differently.

[29]:

The word varṣadhara often wrongly read as varṣavara literally means “one whose seminal discharge has been arrested.”

[30]:

Nirmuṇḍa or aupasthāyika-nirmuṇḍa probably meant one who had the head (muṇḍa) of his membrum virile (upastha) cut off. The definition given here seems to have been due to a concoction when the real significance was lost sight of.

[31]:

Amātya also has been used before to indicate a minister. But AŚ. (1. 8. 9.) distinguishes between amātya and mantrin. Kāmandakīya Nītisāra (VIII. 1) also does the same. According to the latter amātya seems to be identical with saciva (see IV. 25, 30, 31). According to Śukranīti saciva, amātya and mantrin are three different functionaries (See II. 94, 95 and 103). The Rudradāman inscription seems to distinguish between mantrin and saciva.

[32]:

Saciva as well as amātya originally meant secretary.

[33]:

Kumārādhikṛta probably is identical with the Kumārādhyakṣa of

[34]:

B. reads the passage differently. In translation it is as follows: “Those who are high-born, intelligent, well-versed in various Śāstras, affectionate [to the king], incorruptible by enemies, not haughty, the compatriot [of the king], free from greed, disciplined, trust-worthy, and virtuous are to be made chaplains and ministers.” The taking together of the chaplain and the minister probably shows that at one time the same person discharged the functions of the two.

[35]:

See note 1 on 81-83 before.

[36]:

The radical meaning of the term prāḍvivāka is one who decides a cause after questioning the parties.

[37]:

See in this connexion AS.

[38]:

Vyāsa (smṛti) mentions sabhāstāra who should hold discourse about morals (dharmavākya) for the edification of those who are present [in the court]. In Mbh 4. 1. 24 however the sabhāstāra appears only as a courtier (sabhya Nīlakaṇṭha) who is particularly interested in gambling. Jolly, Hindu Law and Customs, pp. 287-288. Viṣṇudharmasūtra first speaks of the qualification of sabhāsadas who were probably the king’s helpers in the administration of justice. N. C. Sengupta, Evolution of Ancient Indian Law, P. 46.

[39]:

That the author of the NŚ. like the authors of the AŚ. refers to Bṛhaspati, probably shows that they were not very widely separated in time. Vātsyāyana, Mbh. (Vanaparvan) and Bhāsa also refer to Bṛhaspati.