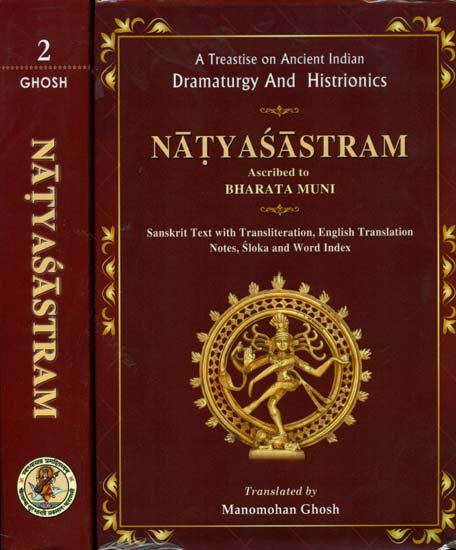

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Chapter XXVII - Success in Dramatic Production (siddhi)

1. I shall now describe the features of the two kinds of Success (siddhi) relating to drama. For the production of a drama is wholly meant for (lit. based on) attaining Success in it.[1]

Two kinds of Success

2. Success [in the dramatic production] which arises from Words, Sattva and Gestures[2] is of two kinds: divine (daivikī), and human (mānuṣī), and relates to various Psychological States and Sentiments.

Human Success

3. [Of these two] the human [Success] has ten features, and the divine [Success] two; and they (i.e. such features) consist [mostly] of various Sattvas expressed vocally (vāṅmayī) and physically (śārīrī).

Vocal Success

4. Slight Smile (smita),[3] Smile (ardhahāsa)[4] and Excessive Laughter (atihāsa),[5] ‘excellent’ (sādhu), ‘how wonderful’ (aho), ‘how pathetic’ (kaṣṭam), and tumultuous applause (pravṛddhanāda, lit. swelling uproar) are the signs of the Success expressed vocally (vāṅmayī).

Physical Success

5. Joy expressed in horripilation, the rising up from the seat and the giving away[6] of clothes (celadāna) and throwing of rings (aṅguli-kṣepa) are signs of the Success expressed physically (śārīrī).[7]

6. When actors produce the Comic Sentiment slightly dependent on words of double entendre, the spectators should always receive the same with a slight Smile[8]

7. When they (i.e. the actors) have a laughter not very clear, or words which do not directly cause laughter, the spectators are always to receive the same with a Smile (ardhahāsya).

8. Laughter created by the bragging of the Jester or by some artifice (śilpa)[9] should always be received by the spectators with an Excessive Laughter (atihāsya)

Vocal Success (again)

9. [Representation of deeds] which relate to the practice of virtue and is endowed with excellence, should be greeted by the spectators with the word “excellent” (sādhu).

10. Similarly, “how wonderful” is naturally uttered by the spectators in connexion with Psychological States like astonishment (vismaya) and to express great joy and the like.

11-12.[10] But in the Pathetic Sentiment they should utter with tears “how pathetic.” And in cases of astonishment there should always be a tumultuous applause (pravṛddhanāda, lit. swelling uproar). Through interrupting exclamation and by horripilation, [the assembly] of spectators are to demonstrate profusely their internal commotion due to a sense of wonder.

13-14. If the play has [a plot containing] burning hostility, cutting and piercing [of limbs], fight, portentous calamity, terrific happening or minor personal combat, it should be received by the expert spectators with tears and rising up [from the seat], and with shaking of the shoulder and head.

15. This is the manner in which the human Success[11] should be expressed. Now listen about the divine Success which I am going to describe.

Divine Success

16. The Success [in dramatic production] which includes an excessive [display] of the Sattva[12] and expresses the Psychological States [clearly] is to be taken by the spectators as divine (daivī).

17. When there is no noise, no disturbance, no unusual occurrence [during the production of a play] and the auditorium is full [of spectators], the Success called divine[13].

Three kinds of Blemish

18. These are the varieties of the Success to be known by the spectators as human and divine. I shall speak hereafter of the Blemishes (ghāta) coming from gods (deva).

19. Blemishes [in the production of a play] are of three kinds; [that coming] from gods[14], from the actors themselves (ātman)[15], and from an enemy (para)[16]. Sometimes a fourth variety of it is what comes up due a portentous calamity.

Blemishes from gods

20. Blemishes from gods are: [strong] wind, fire, rains, fear from an elephant or a serpent, stroke of lightning, appearance of ants, insects, a beast of prey killing[17] of animals.

Blemishes from an enemy

21. Blemishes created by an enemy[18] are: all round screaming, buzzing (viṣphoṭita), noisy clapping, throwing of cow-dung, clods of earth, grass and stones [in the place of performance].[19]

22. Blemishes created by an enemy[20] are considered by the wise to be due to jealousy, hostility [to the party injured], or being partial [to the party’s enemy], or receiving bribe from the latter (arthabheda)[21].

Blemishes due to portents

23. Blemishes resulting from portents (autpātika) are those due to earthquake, storm, the falling of meteors and the like[22].

Self-made Blemishes

I shall now describe Blemishes arising from the actors themselves (ātma-samuttha).

24-25. Unnaturalness [in the acting], wrong movement [of the actors], unsuitability of a role [to an actor] (vibhūmikatva)[23], loss of memory [of the actors], speaking other words[24] (anyavacana i.e. those not in the play), [actor’s] cry of distress[25], want of proper hand movements (vihastatva), falling off of the crown and other ornaments, detects in playing the drums, shyness in of speech, laughing too much and crying too much, are to be taken as obstruction to Success[26].

Serious Blemishes

26-27. Attack of insects and ants wholly spoils the Success, while the falling off of the crown and other ornaments giving rise to a tumultous noise [spoils the production].

27-28. Killing of animals[27] creates hindrance to the production, and the falling off of a crown spoils the excellence. But if taken down voluntarily this will spoil one quarter of the production. But shy speech [of the actors] and the wrong playing of the drums will, [however], wholly spoil Success.

29. The two [kinds of] Blemishes which cannot be remedied in the production of a play are faults due to a natutal calamity, and the running out of water from the Nāḍikā[28].

Palpable sources of Blemishes

30-31. Blemishes in a play are: repetition, defective use of compound words, wrong use of case-endings, want of proper euphonic combination, use of incoherent words, faulty use of three genders, confusion between direct and indirect happenings, lapse in metre, interchange of long and short vowels, and observing wrong caesura[29].

32. Absence of various notes, of sweetness of notes, and of wealth of notes, and ignorance of voice-registers and of tempo, will disturb musical rules [in the production of a play.][30]

33. Non-observance of Sama, Mārga and Mārjanā, giving hard strokes, and ignorance about the [right way of] beginning and the stopping, will spoil the music of drums[31].

34-37. Omission due to loss of memory, and defective enunciation of speeches, putting on ornaments in wrong places, falling off of the crown, not putting on some ornament, an ignorance about mounting or dismounting chariots, elephants, horses, asses, camels, palanquins, aerial cars (vimāna) and vehicles [in general], or confusion about these, wrongly holding or using weapons and armours, entering the stage without the crown, or decoration or entering too late, are the Blemishes which should be marked in proper places by the clever experts, but they should leave out of consideration the sacrificial post, taking up of the fire-wood, Kuśa grass, ladle and other vessels [related to a sacrifice].

Three grades of Blemishes

38. An expert in dramatic production should record Blemishes as “mixed” (miśra), “total” (sarvagata) and “partial” (ekadeśaja), but should not record [merely] Success or Blemishes [without any detailed information about these].

39. Total Success or an all-round Blemish expresses itself in many ways. But a matter affecting merely one aspect [of the production] should not be reckoned for lowering the order [of excellence].

40. After the putting down of the Jarjara [by the Director] in a dramatic production, the Assessors (prāśnika) should always achieve in due manner the accuracy of timing and of recording [of Blemishes as well as goods points].

Wrong Benediction

41. When during a god’s festival, anyone foolishly recites a Benedictory Śloka in honour of a wrong god, it is to be recorded as his Blemish in the Preliminaries.

Interpolation is a Blemish

42. When anyone interpolates the composition of one playwright into that of another, a blemish is be recorded on its strength by the experts.[32]

43. When anyone knowingly interpolates (lit. mixes) in [his] play the name or work of another author, then his Blemish in it being definite, no Success should be recorded.[33]

44. When anyone produces a play in disregard of costumes and languages belonging to a region, then his Blemish relating to the rule of locality, should be recorded[34].

Limitation of human efforts in a play

45. Who is able to observe perfectly the rules of [constructing] plays or producing [them on the stage]? Or who can be bold (lit. eager) enough in mind to [claim to] understand properly all that have been said[35]?

46. Hence one should include in plays words which have deep significance, are approved of by the Vedas as well as the people, and are [generally] acceptable to all persons.[36]

47. And no play (lit. nothing) can be devoid of any merit or totally free from faults. Hence faults in the production of a play should not be made much of.[37]

48. But the actor should not [for that reason] be careless about Words, Gestures and Costumes of minor importance (lit. non-essential) as well as about representing the Sentiments and the Psychological States, dance, vocal and instrumental music and popular usages3 of the same kind [relating to the performance].

An ideal spectator of a performance

49. These are [the rules] defining the characteristics of Success. I shall hereafter describe that of [an ideal] spectator (prekṣaka).

50-53. Those who are possessed of [good] character, high birth, quiet behaviour and learning, are desirous of fame, virtue, are impartial, advanced in age, proficient in drama in all its six limbs, alert, honest, unaffected by passion, expert in playing the four kinds of musical instrument, very virtuous, acquainted with the Costumes and Make-up, the rules of dialects, the four kinds of Histrionic Representation, grammar, prosody, and various [other] Śāstras, are experts in different arts and crafts, and have fine sense of the Sentiments and the Psychological States, should be made spectators in witnessing a drama.2

54. Anyone who has (lit. is characterized by) unruffled senses, is honest, expert in the discussion of pros and cons, detector of faults and appreciator [of merits], is considered fit to be a spectator in a drama.

55. He who attains gladness on seeing a person glad, and sorrow on seeing him sorry, and feels miserable on seeing him miserable, is considered fit to be a spectator in a drama.[38]

56-57. All these various qualities are not known to exist in one single spectator, Hence, because objects of knowledge, are so numerous, and the span of life is so brief, the inferior common persons in an assembly which consists of the superior, the middling and the inferior members, cannot be expected to appreciate the performance of the superior ones.

58. And hence an individual to whom a particular dress, profession, speech and an act belong as his own, should be considered fit for appreciating the same.

Various classes of spectator

59. Different are the dispositions of women and men, young and old, who may be of the superior, middling or inferior type, and on the such dispositions [the Success of] a drama rests.

Disposition of different spectators

60. Young people are pleased in seeing [the presentation of] love, the learned a reference to some [religious or philosophical] doctrine, the seekers of money [topics of] wealth, and the passionless, topics of liberation.

61. Heroic persons are always pleased with the Odious and the Terrible Sentiments, the personal combats and battles, and the old people in tales of virtue and Puraṇic legends, And [the common] women, children and the uncultured men (mūrkha) are always delighted with the Comic situations and [remarkable] Costumes and Make-up.

62. Thus the man who enters the stage (lit. here)[39] by imitating the Psychological States of these, can be considered a spectator possessing the [necessary] qualifications.

Assessors in a performance

63-64. These should be known as spectators in connexion with a drama. But if there be any controversy (saṃgharṣa) [about the performance of individual actors,] the following are the Assessors (prāśnika): an expert in sacrifice, an actor (nartaka), a prosodist, a grammarian, a king, an archer (iṣvāsa), painter, a courtezan, a musician (gandharva) and a king’s officer (rāja-sevaka).[40] Listen about them.

65-68. An expert in sacrifice will be an Assessor in the [representation of], sacrifice an actor in general Histrionic Representation, a prosodist in complicated metres, a grammarian in details of speech, a king in royal character and in connexion with [personal] dignity, and other qualities and in dealing with the harem, the archer (iṣvāsa) in the Sauṣṭhava of the pose, and a painter is a very suitable Assessor of movements, and of Dresses and Make-up which are at the root of dramatic production; a courtezan will be an Assessor in matters relating to the enjoyment of love, and a musician in the application of notes (svara) and in observance of Time (tāla), and an officer of the king in [the matter of] showing courtesies. These are the ten Assessors of a dramatic performance.

69. When there is a controversy about the performance among the persons ignorant of the [Nāṭya]-Śāstra, they are to point out justly the faults as well as the merits [of individual actors].[41] Then they will be known as Assessors of whom I spoke to you.

70. When there occurs any learned controversy about the knowledge of the Śāstra the decision should be made on the testimony of the books (lit. Śāstra).[42]

Controversy about a performance

71. Controversy arises when the actors (bharata) have the desire of mutual contest at[43] the instance of their masters or for [winning] money and the Banner[44] [as rewards].

Procedure in deciding controversies

72. In course of deciding a controversy one should observe [the performance of the parties] without any partiality. The decision about [the award of] the Banner[45] should be according to the stipulation made (paṇam kṛtvā)2 [beforehand].

Recording of Blemishes

73. Blemishes affecting the Success should be recorded with the help of reckoners (gaṇaka) by these persons (i. e. Assessors) who are seated at ease, have clean intention, and whose intelligence is. [generally] relied on [by the public].

Ideal position of Assessors in a performance

74. Assessors should neither be too near [the stage] nor too far [from it]. Their seats should be at a distance of twelve cubits (six yards) from it.

75. They are to notice the the points of the Success mentioned before, as well as Blemishes which may occur during the production of a drama.

Blemishes to be ignored

76. Blemishes which may be accidental (lit. caused by the gods), the portents or the enemy are not to be recorded by the wise [observers]. But the Blemishes relating to the play[46] as well as the Blemishes arising from [the actors] themselves[47] should be recorded.

77.[48] After mentioning him to the king the Banner should be given to a person whose Blemishes, have been reckoned as small in number but points of Success as many.[49]

Procedure of awarding the Banner

78-79. If actors[50] are found to be experts of equal merit in the production of a drama, the Banner should be given to one whose Success is greater, or in case of equal Success [of the two contestants] [the reward should be given] after the king’s decision. If the king has equal admiration for the two rivals, then both of them should be given [a Banner], Those knowing the rules [of the Śāstra] should see in this way that a correct decision is made.

80-81. The spectators who are capable of appreciating merits should sit at ease with an unruffled mind and are to observe the [measure of] achievement as well as the slightest of faults which may relate to the theory of theatrical production, Co-ordination (sama), Charm of Limbs (aṅgamādhurya), Recitatives (pāṭhya), roles, and the Sentiments.

81-82. Hence the Assessors should observe from the beginning songs and instrumental music together with the Costumes and Make-up.

Co-ordination

82-83. Gestures (aṅga) which are made all around in a play in harmony with the different measures of Time in course of dances, related to the Dhruvā[51] songs, is called Co-ordination (sama).

83-84. When in course of the performance [of a play] Gestures of different limbs major and minor, are accompanied with songs, proper Time and tempo and by the playing of drums, it is called Co-ordination.

Charm of Limbs

84-85. The position in which the chest is not bent, the two arms are Caturasra and spread out (āyata) and the neck is (Añcita,) gives rise to the Charm of Limbs (aṅgamādhurya).

85-86. And one should also pay attention to subjects not mentioned before which are to be mastered (sādhya)2 by the actors (sādhaka) and to the instrumental music, the roles (prakṛti), and the songs.

86-87. The Success arising due to joy from the Gestures and the various Sentiments, should be expressed by means of all the signs (lit. the places) of the same.

Probable Time for dramatic performances

87-88. Producers [of plays] should know the time for perfomances day and night distinguish these.

88-89. The performance in the forenoon, mid-day[52] and the afternoon belongs to the day.

89-90. The performance in the evening, the midnight[53] and at dawn belongs to the night.

Time of performance according to the subject and the Sentiment

90-91. I shall now speak how these times are suited to

[different] Sentiments after mentioning the time to which a performance should belong.

91-92. [The performance] which is pleasant to the ear and is based on a tale of virtue (dharma), whether it is pure or mixed, should be held in the forenoon.

92-93. That which is rich in instrumental music, includes a story of strength and energy, and carries [a chance of] abundant Success should be performed in the afternoon.

93-94. That which relates to the Graceful Style, the Erotic Sentiment and is full of vocal and instrumental music1 should be performed in the evening.

94-95. The drama which relates to the magnanimity [of the Hero], and contains mostly the Pathetic Sentiment, should be performed in the morning, and it will scare away sleep.

95-96. The drama should not be performed in the midnight or at noon or at the time of the Sandhyā prayer or of taking meals.

96-97. Thus after looking into the time, place and the basis (plot) of a play one should bring about its production according to the Psychological States and the Sentiments it contains.

Emergency performances are independent of regular time

97-98. But when the patron (lit. master) orders, the time and place are not to be taken into consideration, and the performance should be held without any hesitation.[54]

98-99. Proper Combination (lit. combined production), Brilliance [of Pageant] (samṛddhi), and actors capable of [good] production are the three [points of] merit [in a performance]

Qualities of an actor

99-101. Intelligence, strength, physical beauty, knowledge of Time and tempo, appreciation of the Psychological State and the Sentiments, [proper] age, curiosity, acquisition [of knowledge and arts], [their] retention, vocal music prompted by dance, suppression of stage-fright, and enthusiasm, will be the requisite qualities of an actor (pātra).

An ideal performance

101-102. That which includes good instrumental music, good songs, good recitatives as will as Co-ordination of all acts prescribed by the Śāstra, is called an [ideal] production.

Brilliance of Pageant

102-103. Use of proper ornaments, good garlands, clothes and proper painting or the Make-up [for the characters] gives rise to Brilliance of Pageant (samṛddhi).

The best performance

103. According to the producers of plays, the best (lit. the ornament) [of the performance] occurs when all these factors combine.

104. Thus I have spoken to you properly of the characteristics of Success. Now I shall speak to you about the different branches of music (ātodya, lit. instrumental music)[55].

Here ends Chapter XXVII or Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, which treats of Success in Dramatic Production.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

This chapter discusses the appreciation of theatrical production by spectators who include persons of various types possessing different psychological and cultural traits.

[2]:

vāk-sattvāṅga. These three constitute the Basic Representation. See XXIV.

[3]:

See VI. 52.

[4]:

The ardhahāsa seems to be the same as hasita, smile; see note I above.

[5]:

See note I above.

[6]:

The age-long custom in India was that the wealthy among the spectators on being very highly pleased with a dramatic performance did at once take out from their own body the costly shawls, other wearing apparels or ornaments to give them way to the talented actors. Cf. also NL. 2289f.

[7]:

See note 1 above.

[8]:

This prescription simply points out what should actually happen.

[9]:

For example, the art of comic make-up.

[10]:

The trans. is tentative.

[11]:

This “human” Success seems to relate to the common “human” beings or average spectators, and they should be compared with men occupying the gallery of a modern theatre. They arc generally moved by external and not deep aspects of a dramatic performance. See below 16 note.

[12]:

These are the deeper aspects of a dramatic performance.

[13]:

The “divine” Success seems to relate to cultured spectators who generally take interest in deeper and more subtle aspects of a dramatic performance and as such are above ordinary human beings and may be called “divine.”

[14]:

“Gods” here means the source of various accidents. See 20 below.

[15]:

Their acts of omission or commission are these Blemishes. See below 24-25.

[16]:

See below 21-22.

[17]:

It seems that the killing of animals had then a great attraction for the people.

[18]:

The rival groups of actors who contested for rewards from their patrons, became enemies to one another; see below 72ff.

[19]:

This kind of improper and dishonest acts sometimes occurs also now-a-days in meetings supporting candidates from rival political parties. Human psychology has not much changed since the NŚ. was written more than two thousand years ago.

[20]:

See above 20 note 2.

[21]:

It seems that the leaders of actors did not scruple even to bribe individual spectators to gain their ends.

[22]:

It is possible that due to superstitious fear arising from an appearance of these natural phenomena confusion occurred during the performance.

[23]:

Cf. Ag.

[24]:

Cf. Ag.

[25]:

Cf. Ag.

[26]:

25 a stands cencelled.

[27]:

Cf. Ag.

[28]:

Nāḍikā (text nālikā) is a measure of time. See XX. 66 note 1. The ancient Indian device for measuring time consisted of a water-vessel of particular size with a well-defined tube (nāḍikā) at its bottom. Time required for the complete running out of water from it, was known as a nāḍikā (nāḍī), (See AS. II. 20; also AS. notes, p. 27). Here nāḍikā is used in the sense of the water-vessel for measuring time, On the necessity of time-keeping see below 39 and XX. 23, 65-68. Ag’s explanation does not seem to be clear.

[29]:

Actors and actresses at the time of the NŚ. usually being speakers of Middle Indo-Aryan (Prakrit) and not trained scholars, there occurred all sorts of lapses in their Sanskritic recitation, Hence is to be justified the humorous reference to the naṭa (actor) in a traditional couplet which in trans. is as follows: Where would the vulgarly-used words have gone for fear of hunter like grammarians, if there were no mouth-caves of astrologers, actors, expert gallants (Viṭa), singers and physicians? (Haidar, Itihāsa, p. 143).

[30]:

For the technical terms of music used here see XXVIII.

[31]:

For technical terms of music used here see XXXIII.

[32]:

This seems to show clearly that theatrical managers did not hesitate sometimes to insert passages taken from one playwright’s work into that of another to add to its effect.

[33]:

From this it appears that the practice of putting in the name of the author of a play in the Prologue, was not a very old one. This seems to explain the absence of the author’s name the works ascribed to Bhāsa.

[34]:

From a close study of available plays it does not appear that the rules laid down in the Śāstra were very scrupulously followed; or it is also likely that the rules regarding the use of different languages in a play, changed with the linguistic development as well as other conditions connected with the use of languages.

[35]:

This seems to point out that no Śāstra can exhaustively lay down all the rules which can never be made very clear and precise; for many things in theatre relate to so many fluctuating factors.

[36]:

One should mark the stress put on the Vedas and the popular practice in connexion with the Nāṭya. See XXVI. 118-120.

[37]:

This is a very wise counsel for the hasty critics of a play.

[38]:

The critic must be a man with abundant sympathy.

[39]:

The passage is corrupt, Yasmin in the text may be amended into asmin.

[40]:

This is a very elaborate arrangement for judging in every detail the Success of a performance.

[41]:

The significance of this rule seems to be that when in judging a drama the common people (i.e. who are not acquainted with the rules laid down in the Śāstra) fail to decide, the specialist Assessors mentioned above are to be called in.

[42]:

This rule seems to show that when the specialists in theatrical practice differed, they were to refer to the Śāstra or the traditionally handed down rules compiled in books.

[43]:

An example of this is the contest between the two nāṭyācāryas in the Mālavi.

[44]:

The Indian literary tradition records the fact of Bhāsa’s winning Banners, possibly on the occasion of dramatic contests. See Harṣacarita, Introduction, 15.

[45]:

This stipulation may have the following forms: Success in producing any particular play, or any new play, or a new play with a particular principal Sentiment will entitle one group of actors or its leader to the award of the Banner.

[46]:

See 5-17 above.

[47]:

See 18-44 above.

[48]:

Blemishes relating to a play seems to be its literary drawbacks. It is likely that in dramatic contests choice of defective plays brought discredit on the contestants.

[49]:

See above 24-25.

[50]:

Depending on the vocal applause as well as the silent approbation of spectators.

[51]:

See XXXII.

[52]:

See the note on 97-98 below.

[53]:

See the note on 97-98 below.

[54]:

In view of this, mid-day and mid-night have been included in 87-89 above.

[55]:

For the translation of the remaining portion of the NŚ. (XXVIII-XXXVI) see the Vol. II of this work published by the Asiatic Society, Calcutta, 1961.