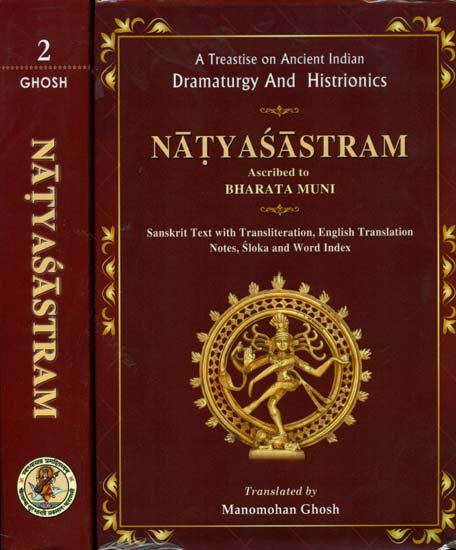

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Chapter XIX - Modes of Address (nāman) and Intonation (kāku)

Different modes of address

1-2. These are, O the best of Brahmins, the rules on the use of languages [in a drama]. Now listen about the rules of popular modes of address[1] or the manner in which persons of equal, superior or inferior status in a play are to be addressed by those of the superior, the medium or the inferior class.[2]

Modes of addressing males: addressing great sages

3. As the great sages are adorable (lit. god) even to the gods they are to be addressed as “holy one” (bhagavan)[3] and their wives are also to be similarly addressed.[4]

Addressing gods, sectarian teachers and learned men

4. Gods,[5] persons wearing sectarian teacher’s dress[6], and persons observing varied vows[7] are to be addressed as “holy one” (bhagavan)[8] by men as well as women.

5. The Brahmin is to be addressed as “noble one” (ārya),[8]

Addressing the king

And the king [is to be addressed] as “great king” (mahārāja).[9]

Addressing the teacher

The teacher [is to be addressed] as “professor” (ācārya).[10]

Addressing an old man

And an old man [is to be addressed] as “father” (tāta).[11]

Brahmins addressing the king

6.[12] Brahmins may address the kings at their pleasure, by their names. This should be tolerated, for the Brahmins are to be adored by the kings.

Brahmins addressing ministers

7. A minister is to be addressed by Brahmins as “Councillor” (amātya) or “minister” (saciva),[13] and by other persons, inferior to them (i.e. Brahmins) he [is] always [to be addressed] as “sir” (ārya).[14]

Addressing the equals

8. One is to accost one’s equals by the name with which they are styled.[15]

Privileged inferiors addressing superiors

A superior person may however be addressed (or referred to) by name by inferior persons when the latter are privileged to do so.[16]

Addressing employees, artisans and artists

9. Men and women in one’s employment,[17] and artisans and artists[18] are to be addressed as such (i.e. according to their status).[19]

Addressing persons of respect

10. A respected person is to be addressed as ‘honoured sir’ (bhāva), and a person slightly less so, as “comrade (mārsaka or mārṣa).[20]

Addressing persons of equal status

A person of equal status should be addressed as ‘brother” (vayasya)[21] and a low person as ‘hey man’ (haṃ-ho)[22]

The charioteer addressing the chariot-rider

11. The chariot-rider should always be addressed by the charioteer as “long-lived one” (āyuṣman).[23]

Addressing an ascetic or a person with beatitude

An ascetic or a person who has attained beatitude (praśānta) is to be addressed as “blessed one” (sādho).[24]

Addressing princes

12. The crown-prince is to be addressed as “sire” (svāmin),[25] and other princes as “young master” (bhartṛ-dāraka).[26]

Addressing inferior persons

Inferior persons are to be addressed as “pleasing one” (śaumya),[27] “auspicious-looking one” (bhadra-mukha)[28] and such terms should be preceded by ‘O’ (he).

Addressing persons by their occupation or birth

13. In a play a person is to be addressed by a term appropriate to his birth or to the vocation, art or learning practised by him.[29]

Addressing a son or a disciple

14. A disciple or a son is to be addressed by the guru or the father as “child” (vatsa)[30], “son” (putraka),[31] “father” (tāta)[32] or by his own name or clan-name (gotra).[33]

15. Buddhist and Jain (nirgrantha) monks are to be addressed as “blessed sir’ (bhadanta).[34]

Addressing persons of other sects

Persons of other sects[35] are to be addressed by terms enjoined by their own rules.[36]

People addressing the king

16. The king is to be addressed by his servants as well as his subjects as “lord” (deva),[37] but when he is an overlord [of other kings] he is always [to be addressed] by his servants as “sire” (bhaṭṭā).[38]

Sages addressing the king

17-18. The king is to be addressed by sages (ṛṣi) as “king” (rājan)[39] or by the patronymic term.[40]

A Jester addressing the king

And he should be addressed as “friend” (vayasya)[41] or “king” (rājan)[42] by the Jester.

A Jester addressing the queen and her maids

The queen and her maids are to be addressed by him as “lady” (bhavati).[43]

A king addressing the Jester

The Jester is to be addressed by the king by his name or as “friend” (vayasya).[44]

Women addressing their husband

19. By all women in their youth the husband should be addressed as a “noble one’s son” (ārya-putra)[45] but in other cases, the husband is to be addressed simply as “noble one” (ārya),[46] and in case of his being a king he may be addressed as “great king” (mahārāja)[47] also.

Addressing the elder and the younger brothers

20. The elder brother should be addressed as “noble one” (ārya)[48] and the younger brother like one’s son.[49]

These are the modes of address to be used to male-characters in a play.

Modes of addressing women

21. I shall now speak of the modes of address to be used to female characters in a play.

Addressing female ascetics and goddesses

Female ascetics and goddesses are to be addressed as “holy lady” (bhagavati).[50]

Addressing wives of senior persons, and elderly ladies

22. Wives of respectable seniors, and of king’s officers (sthānīyā) are to be addressed as “lady” (bhavati).[51]

Addressing an accessible woman and an old lady

An accessible woman (gamyā)[52] is to be addressed as “gentle-woman” (bhadre)[53] and an old lady as “mother” (amba).[54]

Addressing a king’s wives

23. In a play king’s wives are to be addressed by their servants and attendants as “mistress’ (bhaṭṭini), “madam” (svāmini)[55] and “lady” (devi).[56]

24. [Of these], the term “lady” (devi)[57] should be applied to the chief queen (mahiṣī) by her servants as well as by the king. The remaining [wives of the king] may be addressed [simply] as “madam” (svāmini).[58]

Addressing unmarried princesses

25. Unmarried princesses are to be addressed by their handmaids as “young mistress” (bhartṛ-dārikā).[59]

Addressing a sister

An elder sister is to be addressed as “sister” (bhagini)[60] and an younger sister as “child” (vatse).[61]

Addressing a Brahmin lady, a nun or a female ascetic

26. A Brahmin lady, a nun (liṅgasthā) or a female ascetic (vratinī) is to be addressed as “noble lady” (ārye).[62]

Addressing one’s wife

A wife is to be addressed as “noble lady” (ārye)[63] or by referring to her father’s[64] or son’s[65] name.

Women addressing their equals

27. Women friends among their equals are to be accosted by one another with the word “hallo” (halā).[66]

Addressing a handmaid

By a superior woman a handmaid (preṣyā) is to be accosted with the word “hey child” (haṃ-je).[67]

Addressing a courtezan

28. A courtezan is to be addressed by her attendants as Ajjukā,[68] and when she is an old woman she is to be addressed by other characters in a play as Attā.[69]

Addressing wife in love-making

29. In love-making the wife may be accosted as “my dear” (priye)[70] by all except the king. But priests’ and merchants’ wives are always to be addressed as “noble lady” (ārye).[71]

Giving names to different characters in a play

30. The playwrights should always assign significant names [to characters] which are not well-known and which have been created [by them].[72]

Name of Brahmins and Kṣatriyas

31. Of these, Brahmins and Kṣatriyas in a play should, be given, according to their clan or profession, names ending in śarman or varman.[73]

Naming merchants and warriors

32. The names of merchants[74] should end in datta.[75]

To warriors should be given names indicating much valour.[76]

Naming kings wives, and courtezans

33. The king’s wives should be given names [which are connected] with the idea of victory (vijaya).[77]

Names of courtezans should end in dattā,[78] mitrā[79] and senā.[80]

Naming band-maids and menials

34. In a play hand maids should be given the names of various flowers.[81]

Names of menials should bear the meaning of auspiciousness.[82]

Naming superior persons

35. To superior persons should be given names of deep significance so that their deeds may be in harmony with such names.[83]

Naming other persons

36. The rest of persons[84] should be given names suitable to their birth and profession.

Names [that are to be given] to men and women [in a play] have been properly described [by me].

37a. Names in a play should always be made in this manner by the playwright.

37-38. After knowing exhaustively everything about the rules of language in a drama, one should practise Recitation which is to have six Alaṃkāras.

Qualities of Recitation

I shall now describe the qualities of Recitation. In it there are seven notes, three voice-registers, four Varṇas (lit. manner of uttering notes), two ways of intonation (kāku), six Alaṃkāras and six limbs (aṅga). I shall now explain their characteristics.

The seven notes are: Ṣaḍja, Ṛṣabha, Gāndhāra, Madhyama, Pañcama, Dhaivata and Niṣāda. These are to be used in different Sentiments.

Seven notes to suit different Sentiments

38-40. In the Comic and the Erotic Sentiments the notes should be made Madhyama and Pañcama. Similarly in the Heroic, the Furious and the Marvellous Sentiments they should be made Ṣaḍja, and Ṛṣabha. In the Pathetic Sentiment the notes should be Gāndhāra and Niṣāda, and in the Odious and the Terrible Sentiments they should be Dhaivata.

Uses of the three voice-registers

There are three voice-registers: the chest (uras) the throat and the head.

40-41. In the human body as well as in the Vīṇā notes and their pitches proceed from the three registers: the chest, the throat and the head.

41-42. In calling one who is at a distance, notes proceeding from the head register should be used; but, for calling one who is not at a great distance, notes from the throat register is to be used, while for a person who is by one’s side, notes from the chest [will be proper].

42-43. At the time of Recitation, a sentence begun with notes from the chest should be raised to notes of the head register, and at its close it should be brought down to notes of the throat.

Uses of the four accents

43. In Recitation the four accents will be: acute (udātta), grave (anudātta), circumflex (svarita) and quivering (kampita).

Recitation in circumflex and acute accents is suitable to the Comic and the Erotic Sentiments, acute and quivering accent is suitable to the Heroic, the Furious and the

Marvellous Sentiments, while grave, circumflex and quivering accents are appropriate to the Pathetic, the Odious and the Terrible Sentiments.

Two ways of intonation

There are two ways of intonation, e.g. one entailing expectation (sākāṅkṣa) and another entailing no expectation (nirākāṅkṣa). These relate to the sentence uttered.

44. A sentence which has not completely expressed its [intended] meaning, is said to be entailing an expectation, and a sentence which has completely expressed such a sense, is said to be entailing no expectation.

Now, entailing an expectation relates to [the utterance of a sentence] of which the meaning has not been completely expressed and which has notes from the throat and the chest, and begins with a high pitch and ends in a low pitch (mandra) and has not completed its Varṇa or Alaṃkāra.

And, entailing no expectation relates to [the utterance of a sentence] the meaning of which has not been completely expressed and which has notes from the head, and begins with a low pitch (mandra) and ends with a high pitch (tāra) and has completed its Varṇa and Alaṃkāra.

The six Alaṃkāras

45. The six Alaṃkāras of the [note in] Recitation are that it may be high (ucca), excited (dīpta), grave (mandra), low (nīca), fast (druta), and slow (vilambita). Now listen about their characteristics.

Uses of the six Alaṃkāras

The high note proceeds from the head register and is of high pitch (tāra); it is to be used in speaking to anyone at a distance, in rejoinder, confusion, in calling anyone from a distance, in terrifying anyone, in affliction and the like.

The excited note proceeds from the head register and is of extra high pitch (tāratara); it is to be used in reproach, quarrel, discussion, indignation, abusive speech, defiance, anger, valour, pride, sharp and harsh words, rebuke, lamentation and the like.

The grave note proceed from the chest register and is to be used in despondency, weakness, anxiety, impatience, low-spiritedness, sickness, deep wound from weapons, fainting, intoxication, communicating secret words and the like.

The low note proceeds from the chest register, but has a very low pitch (mandra-tara) sound; it is to be used in natural speaking, sickness, weariness due to austerities and walking a distance, panic, falling down, fainting and the like.

The fast note proceeds from the throat register, and is swift; it is to be used in women’s soothing children (lallana) refusal of lover’s overture (manmana),[85] sexual passion, fear, cold, fever, panic, agitation, distressed and secret acts, pain and the like.

The slow note proceeds from the throat register and is of slightly low pitch; it is to be used in love, deliberation, discrimination, anger, envy, saying something which cannot be expressed adequately, bashfulness, anxiety, threatening, surprise, censuring, prolonged sickness, squeezing and the like. [On this subject] there are the following traditional couplets:

46-48. To suit various Sentiments the intonation (kāku) should always be made high, excited and fast in a rejoinder, confusion, harsh reproach, representing sharpness and roughness, agitation, weeping, challenging one who is not present (lit. away from the view) threatening and terrifying [anyone], calling one who is at a distance, and rebuking [anyone].

49-50. Intonation should be made grave and low (nīca) in sickness, fever, grief, hunger, thirst, observation of a lesser vow (niyama), deliberation, deep wound from a weapon, communicating confidential words, anxiety and state of austerities.

51. Intonation should be made grave and fast in women’s soothing children (lalla), refusal to love’s overture (manmana), panic and attack of cold.

52-55. The intonation should be made slow, excited and of low pitch in following an object lost after being seen, hearing anything untoward about a desired object or a person, communicating something desired, mental deliberation, lunacy, envy, censure, saying something which cannot be adequately expressed [by words], telling stories, rejoinder, confusion, an action involving excess, wounded and diseased limb, misery, grief, surprise, jealous anger, joy and lamentation.

56. Grave and slow intonations have been prescribed for words containing pleasant sense and bringing in happiness.

57. Exited and high intonations have been prescribed for words which express sharpness and roughness. Thus the Recitation should be made to have different intonations by the producers.1

Intonation in different Sentiments

58-59. Slow intonation is desired in the Comic, the Erotic, and the Pathetic Sentiments. In the Heroic, the Furious and the Marvellous Sentimets the excited intonation is praised. Fast and low intonations have been prescribed in the Terrible and the Odious Sentiments. Thus the intonation should be made to follow the Psychological States (bhāva) and the Sentiments.

Six limbs of enunciation

Now there are six limbs [of enunciation], such as Separation (viccheda), Presentation (arpaṇa), Closure (visarga), Continuity (anubandha), Brilliance (dīpana) and Calming (praśamana). Of these, Separation (viccheda) is due to pause (virāma). Presentation (arpaṇa) means reciting something by filling up the auditorium with graceful modulation of voice. Closure (visarga) means the finishing of a sentence. Continuity (anubandha) means the absence of separation between words [in a sense group] or not taking breath while uttering them. Brilliance (dīpana) means the gradually augmented notes which proceed from the three voice-registers (sthāna), and Calming (praśamanā) means lowering the notes of high pitch without making them discordant.

Now about their uses in connexion with different Sentiments. In the Comic and the Erotic Sentiments the enunciation should include Presentation, Separation, Brilliance and Calming. In the Pathetic Sentiment it should include Brilliance and Calming. In the Heroic the Furious and the Marvellous Sentiments it should abound in Separation, Calming, Brilliance and Continuity. In the Odious and the Terrible Sentiments it should include Closure and Separation.

All these are to be applied through notes of high, low and medium pitch proceeding [from the three voice-registers] In addressing one at distance, the notes should be made of high pitch from the head; the person addressed being not at a great distance the notes should be made of medium pitch from the throat, and to speak to one at one’s side notes should be made of low pitch from the chest. But one should not proceed to the high pitch from the low one, and from the low pitch to the high one. The three kinds of tempo of these notes are to be utilised in different Sentiments. In the Comic and Erotic Sentiments the tempo should be medium, in the Pathetic it should be slow, and in the Heroic, the Furious, the Marvellous, the Odious and Terrible Sentiments it should be quick.

Pause defined

Now, Pause (virāma) in connexion with enunciation is due to the completion of sense, and is to depend on the situation (lit. practical), and not on metre. Why? Because it is found in practice that there occurs pause even after one, two three or four syllables, e.g.

60. kiṃ, gaccha, mā viśa, sudurjana, vārito’si |

kāryaṃ tvayā na mama, sarva-janopabhukta ||

Tr. What [is the matter]? Be off. Don’t enter. You are barred out, O very wicked man, the enjoyed-by-all, I have nothing to do with you[86].

Use of Pause

Thus in a play (lit. poetical composition) occur words containing small number of syllables in cases of Sūcā[87] and Aṅkura[88] [which are connected with Pause].

Hence, care should be taken about Pause. Why? Because [an observation of] Pause clears the meaning. There is a couplet [on this subject].

61. In the [Verbal] Representaion the producers should always take care about Pause; for, on it depends the meaning [of words uttered].

Hands in connexion with Alaṃkāras and Pause

62. Keeping the eyes fixed in the direction in which the two hands move one should make the Verbal Representation by observing proper Pauses for indicating the [intended] meaning.

63-64. In the Heroic and the Furious [Sentiments] the hands are mostly occupied with the weapons, in the Odious they are bent due to contempt, in the Comic they are to point to [something], in the Pathetic they are to hang down and in the Marvellous they are to remain motionless due to surprise.

65. On similar other occasions too, the meaning should be made clear by means of Alaṃkāras and Pauses.

66-67. Pauses which are prescribed in a verse require Alaṃkāras. Pause should be observed after a word, when the meaning or the breath (prāṇa) requires it. And when words and syllables are combined into a [big] compound or [the utterance is] quick, or confusion about different meanings is liable to arise, Pause should be observed at the end of a foot or as required by the breath. In the remaining cases Pause should depend on the meaning.

Here one should know about the four kinds of syllables known as Drawn-out Syllables (kṛṣyākṣaras) which conform to the proper Sentiments and Psychological States.

Drawn-out syllables and their use

68-69. The consonant ending in a long vowel like o, e, ai, or au is known as a Drawn-out Syllable. In sadness, argumentation, questioning, or indignation, such a syllable should be pronounced by observing proper Kalās of time.

70. As for the rest of the syllables they may be pronounced with Pause required by their meaning, and such a pause may be of one, two, three, four, five or six Kalās duration.

71. The Pause being of greater duration, the syllable pronounced will always be [rendered] long. But its duration should not be more than six Kalās.

72. Or taking account of the practice as required by some cause, or of the particular incident, one should observe Pause in a verse to suit the Psychological State or the Sentiment [involved].

73. In verse, Pauses arising from the foot-division [only] are recognized; but the position of these may be varied on the stage by experts to suit the meaning [of a passage].

74. But [while observing Pause as directed above] one should not create ungrammatical words (apaśabda) or spoil the metre, and one should not pause too long except in places of caesura, and in [uttering words expressing] sorrow one should not make the Intonation excited [dīpta].

75. One should recite a dramatic composition which is free from literary defects, possesses the best characteristics, and has [literary] qualities; in such a Recitation, one should observe proper rules relating to the utterance of notes and their Alaṃkāras.

76. Alaṃkāras and Pauses that have been prescribed in case of Sanskritic Recitation should all be observed in un-Sanskritic (Prakritic) Recitation as well.

77. Thus in the representation of the ten kinds of dramatic work, producers should prepare the Recitation subject to an observance of proper note, Kalā, time (tāla) and tempo (laya).

78. Rules of Intonation have been prescribed [by me] in proper sequence. I shall describe hereafter the ten kinds of dramatic work.

Here ends Chapter XIX of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, which treats of Intonation in connection with the Verbal Representation.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

This manner of addressing different persons includes referring to them before their ownselves or before others, e.g., in Śak. (I), Duṣyanta is referred to by his charioteer as āyuṣmān, āyuṣman paśya paśya).

[2]:

Rules given hereafter do not cover all the numerous and different cases occurring in the exant dramatic literature in Sanskrit and Prakrit.

[3]:

Ex. Kāśyapa (Kaṇva) addressed by his disciple (Śak. IV.) Mārīca by Duṣyanta (ibid. VII.) and Rāvaṇa in ascetic’s disguise by Rāma (Pratimā. V).

[4]:

No ex. of this seems to be available in any extant drama.

[5]:

Ex.: Agni (Abhi. VI). & Varuṇa (ibid. IV).

[6]:

Ex. (Rāvaṇa disguised as an ascetic addressed by Rāma (Pratimā. V.). The Jester in Prātijñā (III) addressing the Jain monk (śramaṇaka) as bhaavam (bhagavan) to create laughter; bhadanta would have been the proper term in this case. See below 15.

[7]:

Read here nānāvratadbara (bha in B) for nānāśrutadhara (B) and nānāśrutidhara (C). Ascetics belonging to minor heterodox sects seem to have been included in this term. Ag. reads nānāśrutadharaḥ and explains this as bahuśrutaḥ.

[8]:

Ex. Brahmin (Keśavadāsa) in Madhyama. addressed by Bhīma.

[9]:

Ex. Sumantra addressing Daśaratha (Pratimā, II), and Vibhīṣaṇa addressing Rāvaṇa (Abhiṣeka II).

[10]:

Ex. Cāṇakya addressed by his disciple (Mudrā, I).

[11]:

Ex. Bharata addressing Sumantra, the old charioteer (Pratimā VI.).

[12]:

Ex. Indra disguised as a Brahmin addressing Karṇa (Kama.), Cf. Cāṇakya addressing Candragupta mostly as Vṛṣala in Mudrā.

[13]:

Cf. XXXIV. 82-83. No example of this rule seems to be available in any extant drama. See note 2 below.

[14]:

Ex. The door-keeper (pratihārī) addressing Yaugandharāyaṇa (Pratijñā, I.). But curiously enough Rākṣasa has been addressed not as ‘Ārya’ but as ‘Amātya’ (counciller) by the door-keeper, and by his friend Virādhagupta too he is addressed likewise (Mudrā, II).

[15]:

Ex. Cāṇakya addressing Rākṣasa and vice versa (Mudrā, VII.).

[16]:

Ex. Haṃsaka referring to Yaugandharāyaṇa before the latter. (Pratijñā. I. 13. 14). See above note 1.

[17]:

Yaugandharāyaṇa addressing Śālaka by name (Pratijñā. I. 2. 4) and the hero Cārudatta addressing the maid-servant Radanīkā (Cāru. I. 21. 13).

[18]:

Ag. explains kāruka and śilpi as follows: artisans (kāruka) are those that build stūpas and the like objects, artists are painters and the like.

[19]:

Ex. The king addressing Haradatta, one of the teachers of dramatic art (Mālavi. II. 12. 4).

[20]:

Ex. pāripārśvika addressing sūtradhāra as bhāva, and sūtra° addressing pāripārśvika as mārṣa (Abhi. I. 1. 6, 8). Śākara once addressing vita as bhāva and next time as māliśa (māriṣa) in Cāru. I. 17. 3; 26. 3.) The word mārṣaka does not seem to occur any extant drama while māriṣa occurs very often. See Uttara. (I. 4. 7) and Mālavi (I. 1. 3).

[21]:

Ex. Siddhārthaka and Samiddhārthaka addressing each other (Mudrā, VI. 2. 14, 16).

[22]:

Ex. Cāṇakya’s spy addressing his disciple as haṃ-ho bambhaṇa, (Mudrā, I. 18. 4).

[23]:

Ex. Duṣyanta’s charioteer addressing him (Śak. I).

[24]:

Ex. Duṣyanta’s priest addressing the two disciples of Kāśyapa (Kaṇva) and Gautamī tapasvinaḥ (Śak. V. II. 6).

The word sādhu as a form of address does not seem to occur in any extant drama.

[25]:

No example of this rule seems to be available in any extant drama. On the other hand svāmin is very often used in addressing a king. Ex. Yaugandharāyaṇa addressing the king Udayana (Svapna. VI. 17. 1). Kauñjāyana and Bhūtika addressiug the king Kuntibhoja (Avi. I. 5. 3; 8. 3). On the use of the word svāmin in inscriptions see Sylvain Levi, Journal Asiatique, Ser. 9, XIX. 95ff. I. Ant. Vol. XXXIII. p. 163. Sitā’s maid addresses Rāma as bhaṭṭā (Pratimā. I. 9. 2). The door-keeper (pratiharī) refers to the crown prince Rāma as bhaṭṭidāraassa rāmassa (Pratimā. I. 2. 9).

[26]:

The word has been used with reference to the crown prince in Pratimā. (loc, cit. i). In referring to other princes play-wrights use the word kumāra. In Pratimā. (III. 14. 12) Bharata has been addressed with this term. In Mudrā, (IV. 12. 5) Malayaketu has been addressed similarly. Avimātaka, the lover of Kuraṅgī is addressed as bhaṭṭidāraa by her maid (Avi. III, 17. 2).

[27]:

This use of the term saumya does not seem to occur in extant dramas, and bbadra appears to have taken its place, e,g. Bharata addressing the messenger (bhaṭa) in Pratimā (III. 4.2). Duṣyanta addresses his chief of the army (senāpati) similarly (Śak. II. 3. 5.4).

[28]:

Ex. Rākṣasa’s spy (purusa) addressing his door-keeper (Mudrā. IV. 8.2). In Abhi, (VI. 31. 1) Agni (god of fire) addresses Rāma as bhadramukha though earlier, (VI. 26, 7) he says; na me namaskāraṃ kartum arhati deveśaḥ. The Jester addresses the caṇḍālas as bho bhaddamuha (Mṛcchakaṭika X, 23. 3). The Māgadha prince is addressed as bhaddamuha by the female ascetic in Svapna 1. 7. 20. For the use of bhadramukha in inscriptions see Select Inscriptions, no, 72. See also Keith. Sanskrit Drama, p. 69.

[29]:

Not many examples of this rule seem to be available in any extant drama. In Mṛcchakaṭika (X. 20.1) Cārudatta’s son addressing the Caṇḍālas as are caṇḍālā may be an example of this.

[30]:

Ex. The Sauvīra king addressing Avimāraka (Avi. VI. 17. 4). Cf. Droṇa addressing Duryodhana (Pañca. 1.22.3).

[31]:

Ex. The form putraka does not seem to occur in any extant play. Droṇa addressing Duryodhana as putra (Pañca I. 23,3.) Duryodhana addressing his son similarly (Uru. I. 42. 3).

[32]:

No example of this seems to be available in any extant drama.

[33]:

Ex, Vālī addressing Aṅgada by name (Abhi, I. 25.2), Kāśyapa (Kaṇva) addressing Śārṅgarava by name (Śak, IV. 16. 1). Instances of a son or a disciple addressed by clan-name (gotra) do not seem to occur is any extant drama.

[34]:

Ex. Kṣapaṇaka addressed by Rākṣasa and Siddhārthaka as bhadanta (Mudrā. IV. 18. 2; V. 2. 1). A Buddhist monk is very rarely met with in extant dramas. Aśvaghoṣa’s drama included such a character, but one cannot say from the fragments how he was addressed. (See Keith, Sanskrit Dr, p. 82)

[35]:

According to Ag. one is to understand by ‘other sects’ Pāśupatas and the like.

[36]:

An example of such a rule is a term like bhāpuṣan or bhāsarvajña used in addressing Pāśupata. teachers (Ag.).

[37]:

Ex. The Kañcukin addressing the king (Mudrā. III. 10. 3). Gaṇadāsa addressing the king (Mālavi. I. 12. 8). Vibhīṣaṇa refers to Rāma as deva (Abhi. VI. 20. 3) when he is not yet a king; besides this the same Vibhīṣaṇa addresses Rāvaṇa as mahārāja (Abhi. III. 15. 1). See also 12 note 1.

[38]:

Ex. Yavanikā addressing the king Duṣyanta (Śak. VI. 24. 10). But in Bāla. (III. 3. i.) the cowherds address Saṅkaraṣaṇa as bhaṭṭā, and Nandagopa too addresses Vāsudeva likewise (Bāla. I. 19. 30).

[39]:

Ex. Bhagavān (Yudhiṣṭhira) addressing the king Virāṭa (Pañca. II. 14. 2).

[40]:

No ex. of this seems to occur in extant dramas. Nārada addresses the two kings simply as Kuntibhoja and Sauvīrarāja in Avi. (VI. 20, 8, 12).

[41]:

Ex. The Jester in Śak. (II. 2. 1) and Mālavi. (V. 3. 18).

[42]:

No example of this seems to occur in any extant drama. In Ratnā. (I. 16. 35) the Jester once addresses the king as bhaṭṭā.

[43]:

Bhavati in the Jester’s speech would be bhodi. Ex. The Jester addressing the queen’s maid in Svapna. (IV. o. 28) also addressing the queen (Mālavi, IV. 4, 23.) and addressing the queen’s maid Susaṃgatā (Ratnā. IV. o. 30).

[44]:

Examples are easily available. See Svapna, Śak. Vikram. etc. The Jester is addressed also as sakhe. See Mālavi. (IV. 1. 1. and Vikram. II, 18. 11. etc.) and as bhadra (Vikram. II. 18. 15).

[45]:

Examples are easily procurable. See Śak, Mālavi, Svapna etc,

[46]:

Ex. Natī in the prologue (prastāvanā) addressing the sūtradhāra her husband (Cāru. and Mudrā).

[47]:

Ex. Gāndhāri addressing Dhṛtarāṣṭra (Ūru. I. 38. 2), Urvaśi refers to the king likewise (Vikram. IV. 39. 2).

[48]:

Ex. Lakṣmaṇa addressing Rāma (Pratimā I. 21. 2). Sahadeva addressing Bhīma (Veṇī. I. 19. 12).

[49]:

Usual from in such a case is vatsa; but the younger brother is also sometimes differently addressed, e. g. by name of the mother, as Saumitre, (Pratimā, I. 21. 1), Kaikeyīmātaḥ, (ibid. IV, 2. 21). See above 14 and 4.

[50]:

The king addressing the privrājikā (Mālavi. I. 14. 2); the Kañcukin addressing the female ascetic (tāpasi) in Vikram. (V. 9. 2).

[51]:

Ex. Sumantra addressing the widowed wives of Daśaratha as bhavatyaḥ (Pratimā. III. 12. 2). The Kañcukin addressing the Pratiharī in Svapna. (VI. o. 6).

[52]:

gamyā—not within the prohibited degree of sexual relationship.

[53]:

Ex. Avimāraka addressing Kuraṅgikā (Avi. III. 19. o). Duṣyanta addressing Priyaṃvadā (Śak. I. 22. 6). But the king addresses Citralekhā as bbadramuhki (Vikram. II. 15. 9). as well as bhadre (ibid. III. 15. o).

[54]:

Ex. The king, Urvaśī and their son addressing the female ascetic. (Vikram, V. 12. 3, 5, 18).

[55]:

Ex. (i) bhaṭṭiṇi, Nipuṇika addressing the queen (Vikram. II. 19. 19); Kañcanamālā addressing the queen (Ratnā I. 18. 11). But in Pratimā (I. 5. 4) the maid (ceṭī) addresses Sītā who is not yet a queen, as bhaṭṭiṇi. (ii) Svāmiṇi as a term of address to the queen docs not seem to occur in any extant drama.

[56]:

Ex. The maid (ceṭī) addressing the queen Bhānumatī (Veṇī. II. 2. 14).

[57]:

See above 23 note 2. For an example of king addressing the queen as devi see Pratijñā. II. 10. 12.

[58]:

No. example of svāmini being used in addressing such a wife seems to occur in any extant drama. In Mālavi. IV. 17. 8 Nipuṇikā addressing Īrāvatī the second wife of Agnimitru uses the term bhaṭṭiṇi.

[59]:

Ex. The maid ( ceṭī) addressing Padmāvatī (Svapna. I. 15. 11) and Kuraṅgī (Avi. III. o. 45).

[60]:

This mode of address does not seem to occur in any extant drama. cf. Karp, I. p. 18.

[61]:

Ex. Yaugandharāyaṇa in the role of an elder brother addresses the queen who is playing the role of his younger sister as vatse (Pratijñā. I. 9. 11).

[62]:

No example of this rule seems to be available in any extant drama. Parivrājikā in Mālavi (I) and the female ascetic in Vikram. (V) could have been addresses as ārye instead of as bhagavati. In Madhyama. Ghaṭokaca addresses the wife of the Brahmin as bhavati.

[63]:

Ex. Sūtradhāra addressing his wife (Mṛcchakaṭika I Malati. I)

[64]:

e.g. Māṭharaputti (Māṭhara’s daughter (Ag), No example seems to occur in any extant drama.

[65]:

e.g, Somaśarma-janani (Somaśarman’s mother) Ag. No example seems to occur in any extant drama.

[66]:

For ex. see Śak, Vikram. etc.

[67]:

Ex. Sītā addressing her maid (Pratimā. I. 4. 21), Īrāvatī addressing Nipuṇikā (Mālavi. III. 14. 1).

[68]:

Ex. the heterae (gaṇikā) addressed by her maid (Cāru. II. o. 6). The word ajjukā (* āryakā, OIA) “madam” afterwards came to mean ‘heterae’ as in the title of the Prahasana Bhagavadajjukīyam by Baudhāyana Kavi.

[69]:

No example of this seems to be available in any extant drama. But the word occurs in the form of attiā in Mṛcchakaṭika (IV. 30).

[70]:

Śakuntalā is addressed as priye by Duṣyanta (Śak. VII. 20. 6), but the occasion is strictly not one of love-making (śṛṅgāra). Udayana while lamenting for Vásavadattā says Hā priye, hā priya-śiṣye etc. (Svapna. I. 12. 53).

[71]:

No example seems to be available in any extant drama.

[72]:

No example of such names seems to occur in any extant drama.

[73]:

No example of such names seems to occur in any extant drama.

[74]:

Ex. Cārudatta the hero of Bhāsa’s play of the same name.

[75]:

B. reads after this one additional hemistich which in translation is as follows: ‘The name of Kāpālikas should end in ghaṇṭa.’ The interpolator had evidently Bhavabhūti’s Aghoraghaṇta (Mālati) in mind.

[76]:

Ex, Vīrasena in Mālavi. (I. 8. 1).

[77]:

No example of this seems to occur in any extant drama.

[78]:

No example seems to occur in any old drama. And the name Vāsavadattā for the queen in several dramas seems to be a clear violation of the rule (See Svapna. Ratnā. etc.).

[79]:

No example seems to occur in any old drama. But Aśoka’s daughter was named Saṃghamittā.

[80]:

Ex, Vasantasenā in Bhāsa’s Cāru, and Śudraka’s Mṛcchakaṭika.

[81]:

Nalinikā in Avi. (II) and Padminikā in Svapna (V) seems to be rare examples of this.

[82]:

Ex, Jayasena the servant (bhaṭa) of the king (Avi. I).

[83]:

No example seems to occur in any extant play.

[84]:

Ex. Brahmacārin (Svapna. I), Viṭa (Cāru.). Devakulika, and Sudhākāra (Pratimā. IV.) etc.

[85]:

On the meaning of lalla (lallana) and manmana there is no unanimity. We follow Ag.’s upādhyāya.

[86]:

These are the words of a vīpralabdhā Heroine.

[87]:

See XXIV. 43.

[88]:

See XXIV. 44.