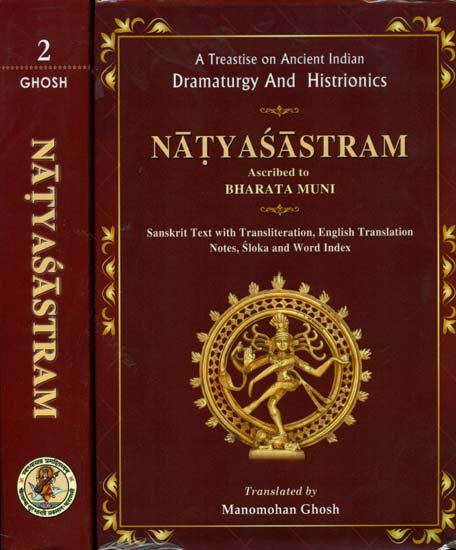

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Chapter XV - Verbal representation (vācika) and Prosody (chandaḥśāstra)

The actor’s speech

1. O the best of Brahmins, I shall now speak about the nature (lit. characteristics of) the Verbal Representation which has been mentioned before[1] and which relates to (lit. arises from) vowels and consonants.

Importance of speech in drama

2. One should take care of words[2]. For these are known as the body of the dramatic art. And Gestures, Costumes and Make-up and the acting of Sattva [merely] clarify the meaning of words.

3. In this world; (lit. here) the Śāstras are made up of words and rest on words; hence there is nothing beyond words, and words are at the source of everything.[3]

4. The Verbal representation is related to [a knowledge of] nouns (nāma), verbs (ākhyāta), particle (nipāta), preposition (upasarga), nominal suffix (taddhita), compound words (samāsa), euphonic combination (sandhi) and case-endings (vibhakti).

Two kinds of recitation

5. The Recitation (pāṭhya) [in a play] is known to be of two kinds Sanskritic and Prakritic. I shall speak of their difference in due order.

Different aspects of Recitation

6-7. [This consists of] vowels, consonants, euphonic combinations, case-endings, nouns, verbs, prepositions, particles and nominal suffixes, The Sanskritic Recitation is characterized by [a due regard to minor rules regarding these as well as] to various verbal roots. Now shall speak briefly about its application.

Speech-sounds

8. The fourteen sounds beginning with ‘a’ and ending in ‘au’, are known as vowels, and the group of sounds beginning with ‘ka’ and ending in ‘ha’ are known as consonants.

Vowels are fourteen in number[4]. a, ā, i, ī, u, ū, ṛ, ḹ (long) ḷ, ḹ (long) e, ai, o and au are to be known as vowels.

The group of letters beginning with ‘ka’, are consonants. ka, kha, ga, gha, ṅa, ca, cha, ja, jha, ña, ṭa, ṭha, ḍa, ḍha, ṇa, ta, tha, da, dha, na, pa, pha, ba, bha, ma, ya, ra, la, va, śa, ṣa sa and ha[5] [constitute] the group of consonants.[6]

Consonants: their articulation

9. [7]The first two sounds of each group [of the stop consonants] are known as unvoiced (aghoṣa) and the rest [of the group] are called voiced (ghoṣa).

10. These [consonants] are to be classified (lit. known as) voiced and unvoiced, velar, labial, dental, lingual (jihvya)[8], nasal, sibilant, palatal and Visarjanīya.

11. In these groups [of consonants] ga, gha, ṅa, ja, jha, ñ, ḍa, ḍha, ṇa, da, dha na, ba bha, ma, ya, ra, la, and va are voiced, while ka, kha, ca, cha, ṭa, ṭha, ta, tha, pa, pha, śa, ṣa, sa and ha are unvoiced.

12-14. Ka, kha, ga, gha, and ṅa, are velar (kaṇṭhastha)1 ca, cha, ja, jha, ña, i, ī, ya and śa palatal, ṭa, ṭha, ḍa, ḍha, ṇa, ṛ, ra, and ṣa cacuminal (mūrdhaṇya), ta, tha, da, dha, na, la, and sa dental, pa, pha, ba, bha, and ma labial; i, c-group, y and ś are labial, ṛ, ṭ-group r and ṣ are cacuminal, and ha are from the throat (kaṇṭhastha). o and au are throat-labial (kaṇṭhoṣṭha-sthāna)[9], e and ai, throat-palatal (kaṇṭha-tālavya).

14-15. The Visarjanīya is from the throat, and ka and [kha] are from the root of the tongue. The place of articulation for pa and pha are lips, and the same will be for the closed (avivṛta) vowels u and ū.

15-16. [The group of sounds] beginning with ka and ending in ma are called stops (sparśa), śa, ṣa sa, and ha are open (vivṛta) while semivowels (antaḥstha) are closed (saṃvṛta) ṅa, ña, ṇa, na and ma are nasal [sounds].

17-18. Śa, ṣa, and sa and ha are sibilants (uṣman, lit. hot); ya, ra, la and va are semivowels (antaḥstha, lit. intermediate), ḥka from the root of the tongue (jihvāmūlīya) and ḥpa from the throat as well as the chest (kaṇṭhorasya)

18-19. The Visarjanīya should be known as a sound from [the root of] the tongue,[10] These are the consonants which have been briefly defined by me. I shall now discuss the vowels with reference to their use in words.

Vowels: their quantity

20. Of the above mentioned fourteen[11] vowels ten constitute homogenous pairs (samāna), of which the first ones are short and the second ones long.

Four kinds of word

21. Constituted with vowels and consonants [described above] the words include verbs (ākhyāta), nouns (nāma,) roots (dhātu), preposition (upasarga) and particles (nipāta), nominal affixes (taddhita), euphonic combinations (sandhi) and terminations for cases and verbs (vibhakti).

22. The characteristics of vocables have been mentioned in details by the ancient masters. I shall again discuss those characteristics briefly.

The noun

23. The noun has its functions determined by the case-endings such as ‘su’ and the like, and by special meanings derived therefrom; and it is of five[12] kinds and has a basic meaning (prātipadikārtha) and gender[13].

24. It (the noun) is known to be of seven[14] classes, and has six cases, and it is well-known as something to be constituted (sādhya), [and when combined thus with different case-endings] it may imply indication (nirdeśa)[15], giving to (sampradāna), taking away (apādāna) and the like.

25. The verbs relate to actions occurring in the present and the past time and the like; they also are well-known as something to be constituted (sādhya), are distinguished and divided according to number and person.

The verb

26. [A collection of] five hundred roots divided into twenty-five[16] classes is to be known as verbs in connexion with the Recitation, and they add to the meaning [of the nouns].

27. Those that upasṛjanti (modify) by their own special significance the meaning of the verbal roots included in the basic words are for that [very] reason called upasarga[17] (preposition) in the science of grammar (saṃṣkāra-śāstra).

The particle

28.[18] As they nipatanti (come together) with declined words (pada) to strengthen their basic meaning, root, metre[19] or etymology[20], they are called nipata (particles).

The affixes

29.[21] As it distinguishes ideas (pratyaya) and develops the meaning [of a root] by intensifying it or combining [it with another] or [pointing out] its essential quality (sattva), it is called pratyaya (affix).

The nominal affix

30.[22] As it develops suitable meanings [of a word] by an elision [of some of its sounds], a separation [of its root and affix] or their combination and by [pointing out] an abstract notion, it is called taddhita (nominal affix).

The case-ending

31. As they vibhajanti (distinguish between) the meaning of an inflected word or words with reference to their roots or gender, they are called vibhakti (case-endings).[23]

The euphonic combination

32. Where a separated vowel or a consonant sandhīyate (combines with another)[24] by coming together[25] (yogataḥ) in a word or words, it is called sandhi (euphonic combination).

33. As due to the combination of words and the meeting of two sounds (lit. letters) their sound sequence (karma - saṃbandha) sandhīyate (develops in a combination), it is called sandhi (euphonic combination).

Compound words

34. The Samāsa (compound word) which combines many words to express a single meaning, and suppresses affixes, has been described by the experts to be of six kinds, such as Tatpuruṣa and the like.

35. With these rules of grammar (śabda-vidhāna) which include minute details and suggestiveness, one should make a composition by combining words in verse or putting them loosely in prose.

Two kinds of word

36. Padas are inflected words, and are of two kinds, viz. those metrically used and those loosely put together in prose, Now listen [first] about the characteristics of words loosely used in prose.

Words in prose

37. Padas used loosely in prose are not schematically combined, have not the number or their syllables regulated, and they contain syllables required [only] to express the meaning [in view].

Words in verse

38. Padas metrically used consist of schematically combined syllables which have feet and caesura, and which have their number regulated.

Syllabic metres

39. Thus arises a Rhythm-type (chandas) called Vṛtta (syllablic metre) made up of four feet which expresses different ideas and consists of [short and long] syllables.

Rhythm-types

40-41. Rhythym-types with feet are twenty-six in number. Vṛttas (syllabic metres) which are compositions including these Rhythm-types, are of three kinds, viz. even (sama), semi-even (ardha-sama) and uneven (viṣama).

41-42. These Rhythm-types which assume the form of different syllabic metres, have their bases in words. There is no word, without rhythm and no rhythm without a word. Combined with each other they are known to illuminate the drama.

Twenty-six Rhythm-types

43-49. [The Rhythm-type] with one syllable [in a foot] is called Uktā, with two syllables is Atyuktā, with three syllables Madhyā, with four syllables Pratiṣṭhā, with five syllables Supratiṣṭhā, with six syllables Gāyatrī, with seven syllables Uṣṇik with eight syllables Anuṣṭup, with nine syllables Bṛhatī, with ten syllables Paṅkti, with eleven syllables Triṣṭup, with twelve syllables Jagatī, with thirteen syllables Atijagatī, with fourteen syllables Śakkarī, with fifteen syllables Atiśakkarī, with sixteen syllables Aṣṭi, with seventeen syllables Atyaṣṭi, with eighteen syllables Dhṛti, with nineteen syllables Atidhṛti, with twenty syllables Kṛti, with twenty-one syllables Prakṛti, with twenty-two syllables Ākṛtī, with twenty-three syllables Vikṛti, with twenty-four syllables Saṃkṛti, with twenty-five syllables Atikṛti, and with twenty-six syllables Utkṛti.

Possible metrical patterns

49-51. Those containing more syllables than these are known as Mālā-vṛttas. And the Rhythm-types being of many different varieties, metrical pattens according to the experts[26] are innumerable. The extent of these such as Gāyatrī and the like, is being given [below]. But all of them are not in use.

51-76. [Possible] metrical patterns of the Gāyatrī [type] are sixty-four, of the Uṣṇik one hundred and twenty-eight, of the Anuṣṭup two hundred and fifty-six, of the Bṛhatī five hundred and twelve, of the Paṅkti one thousand and twenty-four, of the Triṣṭup two thousand and forty-eight, of the Jagatī four thousand and ninety-two, of the Śakkari, sixteen thousand three hundred and eighty-four, of the Atiśakkarī thirty-two thousand seven hundred and sixty-eight, of the Aṣṭi sixty-five thousand five hundred and thirty-six, of the Atyaṣṭi one lac thirty one thousand and seventy-two, of the Dhṛti two lacs sixty-two thousand one hundred and forty-four, of the Atidhṛti five lacs twenty-four thousand two hundred and eighty-eight, of the Kṛti ten lacs forty-eight thousand five hundred and seventy-six, of the Prakṛti twenty lacs ninety-seven thousand one hundred and fifty-two, of the Ākṛti[27] forty-one lacs ninety-four thousand three hundred and four, of the Vikṛti eighty-three lacs eighty thousand six hundred and eight, of the Saṃkṛti one crore sixty-seven lacs seventy-seven thousand two hundred and sixteen, of the Abhikṛti (Atikṛti) three crores thirty-five lacs fifty-four thousand four hundred and thirty-two, of the Utkṛti six crores seventy-one lacs eight thousand eight hundred and sixty-four.

77-79. Adding together all these numbers of different metrical patterns we find their total as thirteen crores forty-two lacs seventeen thousand seven hundred and twenty-six.

Another method of defining metres

79-81. I have told you about the even metres by counting [their number]. You should also know how the triads make up the syllabic metres. Whether these are one, twenty thousand or a crore, this is the rule for the formation of all the syllabic metres or metres in general.

81-82. Triads are eight in number and have their own definitions. Three syllables heavy or light, or heavy and light make up a triad which is considered a part of each metrical pattern.

83-84. [Of these eight triads] bha contains two light syllables preceded by a heavy one (⎼⏑⏑), ma three heavy syllables (⎼⎼⎼), ja two light syllables separated by a heavy syllable(⏑⎼⏑), sa two light syllables followed by a heavy syllable (⏑⏑⎼) ra two heavy syllables separated by a light one (⎼⏑⎼), ta two heavy syllables followed by a light one(⎼⎼⏑) ya two heavy syllables preceded by a light one and (⏑⎼⎼), na three light syllables (⏑⏑⏑).

85-86. These are the eight triads having their origin in Brahmā. For the sake of brevity or for the sake of metre they are used in works on prosody, with or without [inherent] vowels (i.e. a).

86-87. A single heavy syllables should be known as ga and such a light syllable as la.

Separation of two words [in speaking a verse] required by rules [of metre] is called caesura (yati).

87-88. A heavy syllable is that which ends in a long or prolated (pluta) vowel, Anusvāra, and Visarga or comes after a conjunct consonant or sometimes occurs at the end [of a hemistich].

88-89. Rules regarding the metre, relate to a regular couplet (sampat), pause, foot, deities, location, syllables, colour, pitch and hyper-metric pattern.

A regular couplet

89-90. A couplet in which the number of syllables is neither in excess nor wanting is called a regular one (sampat).

The pause

90-91. The pause (virāma) occurs when the meaning has been finally expressed.

The foot

The foot (pada) arises from the root pad, and it means one quarter [of a couplet].

Presiding deities of metres

91-92. Agni and the like presiding over different metres are their deities.

Location

Location is of two kinks, viz, that relating to the body and that to a [particular] region.

Quantity of syllables

93. Syllables are of the three kinds, viz. short, long and prolated (pluta).

Colours of metres

Metres have colours like white and the like.

Pitch of vowels

94-95. The pitch of vowels is of three kinds, viz. high, low and medium. I shall speak about their character in connexion with the rules of Dhruvās. Rules [about their use] relate to the occasion and the meaning [of thing sung or recited].

Three kinds of syllabic metre

95-97. Syllablic metres are of three kinds, viz, even (sama), semi-even (ardha-sama) and uneven (viṣama).

If the number of syllables in a foot of any metre is difficient or in excess by one, it is repectively called Nivṛt or Bhurik. If the deficiency or excess is of two syllables, then such a metre is respectively called either Svarāṭ or Virāṭ.

98. All the syllabic metres fall into three classes such as divine, human and semi-divine.

99. Gāyatrī, Uṣṇik, Anuṣṭup, Bṛhatī, Triṣṭup and Jagatī belong to the first or the divine (divya) class.

100. Atijagatī, Śakkarī, Atiśakkarī, Aṣṭi, Atyaṣṭi, Dhṛti and Atidhṛti belong to the next (i.e. human) class.

101. Kṛti, Prakṛti, Vyākṛti (Ākṛti), Vikṛti, Saṃkṛti, Abhikṛti (Atikṛti) and Utkṛti belong to the semi-divine class.

102. O the best of Brahmins, now listen about the metrical patterns which are to be used in plays and which are included in the Rhythm-types described by me[28].

Here ends Chapter XV of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, which treats of the Verbal Representation and the Rules of Prosody.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

For the four kinds of Histrionic Representation which includes the Verbal one see VI. 23.

[2]:

This rule applies to the actors as well as to the play-wright. See Ag. on this.

[3]:

This view is also held by Bhatṛhari (circa 600 A.C.) in his Vākyapadīya (Āgamakāṇḍa). See B, p. 224, footnote.

[4]:

Different Śikṣās and Prātiśākhyas enumerate vowels differently. According to the PŚ. they are 22 in number, while the Atharva, Taittirīya, and Vājasaneyī Prātiśākhyas and the Ṛktantra Vyākaraṇa (Sāmaveda Pr.) give their number respectively as 13, 13, 16, 23 and 23. See PŚ. (ed. Manomohan Ghosh) p. 51.

[5]:

PŚ. count anusvāra, visarga, jihvāmūlīya and upadhmānīya among consonants. See ed. Ghosh, p. 50.

[6]:

B, reads after this a couplet (B. 10) from PŚ, See ibid, p. 59. Not occurring in most of the mss. this may be taken as spurious. This is followed in B. by a prose passage which also seems to be such. The same is our view about the couplet B. 11 which follows this prose passage. The substance of this couplet (B. 11) occurs in 9 below.

[7]:

In C. this couplet occurs after 8 and before the prose passage that follows it.

[8]:

The jihvya does not seem to occur in any well-known grammatical work. This is perhaps synonymous with mūrdhaṇya; for in the production of mūrdhaṇya sounds jihvā (tongue) plays the most important part. The Taittirīya Pr. describes the manner of their production as follows: Jihvāgreṇa prativeṣṭya mūrdhaṇi ṭa-vargasya (II. 37). Curiously enough the term jihvya has never again been used in the NŚ.

[9]:

For different traditional views about the places of articulation of consonants see PŚ. p. 62.

[10]:

See note 1 to 12-14 above.

[11]:

About the number of vowels see 8 note 1 above.

[12]:

Five kinds of noun have been enumerated by Govīcandra, in the Saṃkṣiptasāra-vivaraṇa (Ref. Haidar, Itihāsa, p. 174).

[13]:

There is a difference of opinion about the number of basic meanings (prātipdikārtha) of a word. According to Pāṇini they are two: charcteristics of a species (jāti) and object (dravya). Kātyāyana adds one more to the number which is gender (liṅga). But Vyāghrapāt—a rather less known ancient authority—took their number to be four. According to him they are: characteristics of a species, object, gender and number (saṃkhyā). Patañjali however considered them to be five in number, e.g. characteristics of a species, object, gender, number and case (kāraka). (Haidar, Itihāsa p. 447-48.

[14]:

The seven classes probably relate to the seven groups of case-ending.

[15]:

Nirdeśa seems to relate ‘nominatives’; for it is one of the meanings of the case-endings. For an enumeration of these see Haidar, Itihāsa, p. 170.

[16]:

There are different numbers of roots in lists (Dhātupāṭha) attached to different grammatical works. It is not known which gives their number as five hundred. Dhanapāla (970 A.C). in his commentary to Jaina Śākaṭāyana’s Dhātupāṭha gives some information on the subject. See Haidar, Itihāsa, pp. 44), Verbal roots arc divided according to Pāṇini into ten classes (gaṇa). Their division into twenty-five classes does not seem to occur in any well-known work.

[17]:

This definition of the upasarga follows Śākaṭāyana’s view on the subject as expressed in the Nirukta (I.1.3-4). According to this authority upasargas have no independant meaning, and they are merely auxiliary words modifying of the verbal roots. (Haidar, Itihāsa, p. 346).

[18]:

According to Pāṇini indeclinables (avyaya) of the ca -group are particles (nipāta). See I, 5.57. According to Patāñjalī nipātas do the function of case-endings and intonation (svara—pitch accent), (on P.III.4.2) The author of the Kāśikā too accepts this view in this comments on P. I, 4.57.

[19]:

Ca, vai, tu, and hi are instances of such nipātas.

[20]:

It is not clear how nipātas, strengthen the etymology given here. Probably the reading here is corrupt.

[21]:

Such an elaborate definition of the pratyaya does not not appear to occur in any exant grammatical work. Ag. seems to trace it to the Aindra school of grammarians. The meaning of the definition is not quite clear. According to the common interpretation the pratyaya means that which helps to develop a meaning from root.

[22]:

This definition of the taddhita does not seem to occur in any well-known grammatical work. It describes the processes through which the taddhita suffix transforms a word.

[23]:

This definition follows the etymological sense of the term (vibhakti). Durgasiṃha of the Kalāpa school says that the case-endings are so called because of their giving distinctive meaning to a word. See Haidar, Itihāsa, p. 169.

[24]:

The sandhi is strictly speaking, not merely a combination of two sounds (vowels or consonants); in a great number of cases their mutual phonetic influence constitutes a sandhi, This is of five kinds, and relate to savara-s, vyañjana-s, prakṛti-s, anusvāra-s, and visarga-s.

[25]:

This ‘coming together’ depends on the shortness of duration which separates the utterance of the two sounds. According to the ancient authorities sandhi will take place when this duration will not be more than half a mātrā, It is for this reason that the two hemistichs in a couplet are never combined. (Hāldar, Itihāsa p. 166).

[26]:

They are mathematicians like Bhāṣkarācārya. See Līlāvātī, section 84, (ed. Jīvānanda, p. 50). Couplets following this are mostly spurious. See Introduction to the text.

[27]:

Ślokas giving the numbers of metres of the ākṛti, vikṛti, saṃkṛti, abhikṛti (atikṛti) and utkṛti classes seems to be corrupt in C.

[28]:

Some versions of the NŚ. read this couplet as the beginning of the next chapter.