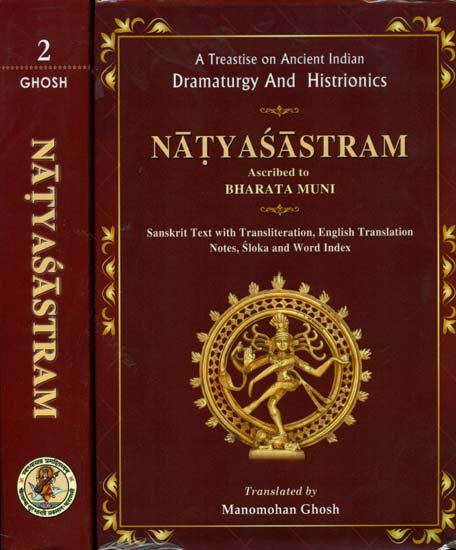

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Chapter II - Description of the Playhouse (nāṭyamaṇḍapa)

1-2. On hearing Bharata’s words, the sages said, “O the holy one, we would like to hear about the ceremony relating to the stage.[1] And how are the men of future to offer Pūjā in the playhouse or [to know about] the practices related to it, or its accurate description?

3. As the production of a drama begins with the playhouse (nāṭyamaṇḍapa), you should [first of all] give us its description.”

Three types of a playhouse

4. On hearing these words of the sages, Bharata said, “Listen, O sages, about the description of a playhouse[2] and of the Pūjā to be offered in this connexion.

5-6. Creations of gods [observed] in houses and gardens are the outcome of their [mere] will; but men’s [creative] activity should be carefully guided by rules [laid down in the Śāstras]. Hence, listen about the method of building a playhouse and of the manner of offering Pūjā at the site [of its construction].

7-8. There are three types of playhouse devised by the wise Viśvakarmā [the heavenly architect] in the treatise on his art (śāstra). They are oblong (vikṛṣṭa) square (caturaśra) and triangular (tryasra).

Three sizes of the playhouse

8-11. Their sizes vary: they may be large (jyeṣṭha), middle-sized (madhya) and small (avara).[3] The length (lit. measurement) of these [three types] fixed in terms of cubits as well as Daṇḍas, is one hundred and eight, sixtyfour or thirtytwo. They[4] should [respectively] have [sides] one hundred and eight, sixtyfour and thirtytwo [cubits or Daṇḍas][5] long. The large playhouse is meant for gods[6] and the middle-sized one for kings, while for the rest of people, has been prescribed the smallest [theatre].[7]

The table of measurement

12-16. Listen now about the measurement of all these theatres, which has been fixed by Viśvakarmā. Units of these measurements[8] are: Aṇu, Raja, Bāla, Likṣā, Yūkā, Yava, Aṅgula, cubit (hasta) and Daṇḍa.

8 Aṇus = 1 Raja,

8 Rajas = 1 Bāla,

8 Bālas = 1 Likṣā,

8 Likṣās = 1 Yūkā,

8 Yūkās = 1 Yava,

8 Yavas = 1 Aṅgula,

24 Aṅgulas = 1 Hasta (cubit),

4 cubits = 1 Daṇḍa

With the preceding table of measurement I shall describe them (i.e. the different classes of playhouse).

A playhouse for mortals

17. An [oblong] playhouse meant for mortals[9] should be made sixtyfour cubits in length and thirtytwo cubits in breadth.

Disadvantage of a too big playhouse

18-19. No one should build a playhouse bigger than the above; for a play [produced] in it (i.e. a bigger house) will not be properly expressive. For anything recited or uttered in too big a playhouse will be losing euphony [for the hearers] due to weak resonance of the sounds uttered.[10]

20. [Besides this] when the playhouse is very big, the expression in the face [of actors] on which rests the Representation of States and Sentiments, will not be distinctly visible [to all the spectators].

21. Hence it is desirable that playhouses should be of medium size, so that the Recitatives as well as the songs in it, may be more easily heard [by the spectators].

22-23. Creations of gods [observed] in house and gardens are the outcome of their [mere] will, while men are to make careful efforts in their creation; hence men should not try to rival the creation of gods.[11] I shall now describe the characteristics of a [play] house suitable for human beings.

Selection of a suitable site

24. The expert [builder] should first of all examine a plot of land and then proceed with a good resolve to measure the site of the building.

25. A builder should erect a playhouse on the soil which is plain, firm, hard, and black or not white.

26. It should first of all be cleared and then scratched with a plough, and then bones, pegs, potsherds in it as well as grass and shrubs growing in it, are to be removed.

Measurement of the site

27a. The ground being cleared one should measure out [the building site].[12]

27-28. Under the asterism Puṣyā (Cancri) he should spread [for measurement] a piece of white string which may be made of cotton, wool, Muñjā grass or bark of some tree.

Taking up the string

28-31. Wise people should prepare for this purpose a string which is not liable to break. When the string is broken into two [pieces] the patron[13] [of the dramatic spectacle] will surely die. When it is broken into three a political disorder will occur in the land, and it being broken into four pieces the master of the dramatic art[14] will perish, while if the string slips out of the hand some other kind of loss will be the result. Hence it is desired that the string should always be taken and held with [great] care. Besides this the measurement of ground for the playhouse should be carefully made.

32-33. And at a favourable moment which occurs in a (happy) Tithi[15] during its good part (su-kaṛaṇa)[16] he should get the auspicious day declared after the Brahmins have been satisfied [with gifts]. Then he should spread the string after sprinkling on it the propitiating water.

The ground-plan of a playhouse

33-35. Afterwards he should measure a plot of land sixtyfour cubits [long][17] and divide the same [lengthwise] into two [equal] parts. The part which will be behind him (i.e. at his back) will have to be divided again into two equal halves. Of these halves one [behind him] should be again divided equally into two parts, and on one of these will be made the stage (raṅga-śīrṣa) and on the part at the back the tiring room.

The ceremony of laying the foundation

35-37. Having divided the plot of land according to rules laid down before, he should lay in it the foundation of the playhouse. And during this ceremony [of laying the foundation] all the musical instruments such as, Śaṅkha (conchshell), Dundubhi[18], Mṛdaṅga[19] and Paṇava[20] should be sounded.

37-38. And from the places for the ceremony, undesirable persons such as heretics[21] including Śramaṇas,[22] men in dark red (kāṣāya)[23] robes as well as men with physical defects, should be turned out.

38-39. At night, offerings should be made in all the ten directions [to various gods guarding them] and these offerings should consist of sweet scent, flowers, fruits and eatables of various other kinds.

39-41. The food-stuff offered in [the four cardinal directions] east, west, south and north, should respectively be of white, blue, yellow and red colours. Offerings preceded by [the muttering of] Mantras should be made in [all the ten] different directions to deities presiding over them.

41-42. At [the time of laying] the foundation ghee[24] and Pāyasa[25] should be offered to Brahmins, Madhuparka[26] to the king, and rice with molasses to masters [of dramatic art].

42-43. The foundation should be laid during the auspicious part of a happy Tithi under the asterism Mūlā (Lambda-Scorpionis).

Raising pillars of the playhouse (nāṭyamaṇḍapa)

43-45. After it has been laid, walls should be built and this having been completed, pillars within the playhouse should be raised in an [auspicious] Tithi and Karaṇa[27] which are under a good asterism. This [raising of pillars] ought to be made under the asterism Rohiṇī (Aldeberan) or Śravaṇā (Aquillae) [which are considered auspicious for the purpose].

45-46. The master [of dramatic art], after he has fasted for three [days and] nights, is to raise the pillars in an auspicious moment at dawn.

46-50.[28] In the beginning, the ceremony in connexion with the Brahmin pillar should be performed with completely white,[29] articles purified with ghee and mustard seed; and in this ceremony Pāyasa should be distributed [to Brahmins]. In case of the Kṣatriya pillar, the ceremony should be performed with cloth, garland and unguent which should all be of red[30] colour; during the ceremony rice mixed with molasses should be given to the twice-born caste. The Vaiśya pillar should be raised in the north-western direction of the playhouse (nāṭyamaṇḍapa) and [at the ceremony of its raising] completely yellow[31] articles should be used, and Brahmins should be given rice with ghee. And in case of the Śūdra pillar, which is to be raised in the north-eastern direction, articles used in offering should all be of dark[32] colour, and the twice-born caste should be fed with Kṛsarā.

50-53. First of all in case of the Brahmin pillar, white garlands and unguent as well as gold from an ear-ornament should be thrown at its foot, while copper, silver, and iron are respectively to be thrown at the feet of the Kṣatriya, Vaiśya and Śūdra pillars. Besides this, gold should be thrown at the feet of the rest [of pillars].

53-54. The placing of pillars should be preceded by the display of garlands of [green] leaves and the utterance of ‘Let it be well’ (svasti) and ‘Let this be an auspicious day’ (puṇyāha).

54-57. After pleasing the Brahmins with considerable (analpa) gift of jewels, cows and cloths, pillars should be raised [in such manner that] they do neither move nor shake nor turn round. Evil consequences that may follow in connexion with the raising of pillars, are as follows: when a pillar [after it has been fixed] moves drought comes, when it turns round fear of death occurs, and when it shakes fear from an enemy state appears. Hence one should raise a pillar free from these eventualities.

58-60 In case of the holy Brahmin pillar, a cow[33] should be given as fee (dakṣiṇā) and in case of the rest [of the pillars] builders should have a feast. And [in this feast foodstuff] purified with Mantra should be given by the wise master of the dramatic art. And the priest and the king should be fed with honey and Pāyasa. Then the workers should be fed Kṛsarā[34] and salt.

60-63. After all these rules have been put into practice and all the musical instruments have been sounded, one should raise the pillars with the muttering over them of a suitable Mantra [which is as follows]: ‘Just as the mount of Meru is immovable and the Himālaya is very strong, so be thou immovable and bring victory to the king.’ Thus the experts should build up pillars, doors, walls and the tiring room, according to rules.

The Mattavāraṇī

63-65. On [each] side of the stage should be built the Mattavāraṇī[35] and this should be furnished with four pillars and should be equal in length to the stage, and its plinth should be a cubit and a half high.[36] And the plinth of the auditorium (raṅgamaṇḍala) should be equal in height to that of the two [Mattavāraṇīs].

65-67. At the time of building them (the two Mattavāraṇīs) garlands, incense, sweet scent, cloths of different colour as well as offerings agreable to Bhūtas should be offered [to them]. And to ensure the good condition of the pillars, one should give to the Brahmins Pāyasa[37] and other eatables such as Kṛsarā. The Mattavāraṇīs should be built up after observing all these rules.

The stage

68. Then one should construct the stage after a due performance of all the acts prescribed by rules, and the stage should include six piece of wood.

69-71. The tiring room should be furnished with two doors.[38] In filling up [the ground marked for the stage] the black earth should be used with great care. This earth is to be made free from stone chips, gravel and grass by the use of a plough to which are to be yoked two white draught animals. Those who will do [the ploughing] work should be free from physical defects of all kinds. And the earth should be carried in new baskets by persons free from defective limbs.

72-74. Thus one should carefully construct the plinth of the stage (raṅgaśīrṣa).[39] It must not be [convex] like the back of a tortoise or that of a fish. For a stage the ground[40] which is as level as the surface of a mirror, is commendable. Jewels and precious stones should be laid underneath this by expert builders. Diamond is to be put in the east, lapis lazuli in the south, quartz in the west and coral in the north, in the centre gold.

Decorative work in the stage

75-80. The plinth of the stage having been constructed thus, one should start the wood-work which is based on a carefully though out (ūha-pratyūha-saṃyukta)[41] [plan], with many artistic pieces such as decorative designs, carved figures of elephants, tigers and snakes. Many wooden statues also should be set up there, and this wood-work [should] include Niryūhas,[42] variously placed mechanized latticed windows, rows (dhāraṇī) of good seats, numerous dove-cots and pillars raised in different parts of the floor.[43] And the wood-work having been finished, the builders should set out to finish the walls. No pillar, bracket,[44] window, corner or door should face a door.[45]

80-82. The playhouse (nāṭyamaṇḍapa) should be made like a mountain cavern[46] and it should have two floors[47] [on two different levels] and small windows; And it should be free from wind and should have good acoustic quality. For [in such a playhouse] made free from the interference of wind, voice of actors and singers as well as the sound of musical instruments[48] will acquire volume.

82-85. The construction of walls being finished, they should be plastered and carefully white-washed. After they have been smeared [with plaster and lime], made perfectly clean and beautifully plain, painting should be executed on them. In this painting should be depicted creepers, men, women, and their amorous exploits.[49] Thus the architect should construct a playhouse of the oblong type.

Description of a square playhouse

86-92. Now I shall speak of the characteristics of that of the square[50] type. A plot of land, thirty-two cubits in length and breadth, is to be measured out in an auspicious moment, and on it the playhouse should be erected by experts in dramatic art. Rules, definitions and propitiatory ceremonies mentioned before [in case of a playhouse of the oblong type] will also apply in case of that of the square type. It should be made perfectly square and divided into requisite parts[51] by holding the string [of measurement], and its outer walls should be made with strong bricks very thickly set together. And inside the the stage and in proper directions [the architect] should raise ten pillars[52] capable of supporting the roof. Outside the pillars, seats should be constructed in the form of a staircase by means of bricks and wood, for the accommodation of the spectators. Successive rows of seats should be made one cubit higher than those preceding them, and the lowest row of seats being one cubit higher than the floor. And all these seats should overlook the stage.

92-95. In the interior of the playhouse six more strong pillars capable of supporting the roof should be raised in suitable positions and with [proper] ceremonies (i.e., with those mentioned before). And in addition to these, eight more pillars should be raised by their side. Then after raising [for the stage or raṅgapīṭha ] a plinth eight cubit [square, more] pillars should be raised to support the roof of the playhouse. These [pillars] should be fixed to the roof by proper fasteners, and be decorated with figurines of ‘woman-with-a-tree’ (sālastrī—śālabhañjikā[53])

95-100. After all these have been made, one should carefully construct the tiring room. It should have one door leading to the stage through which persons should enter with their face towards [the spectators]. There should also be a second door facing the auditorium. The stage [of the square playhouse] should be eight cubits in length and in breadth. It should be furnished with an elevated plinth with plain surface, and its Mattavāraṇī should be made according to the measurement prescribed before (i.e., in case of the oblong type of playhouse). The Mattavāraṇī should be made with four pillars by the side[54] of the plinth [mentioned above]. The stage should be either more elevated than this plinth or equal to it in height. In case of a playhouse of the oblong (utkṛṣṭa) type, it should be higher than the stage, whereas in a playhouse of the square type it should have a height equal to that of the stage. These are the rules according to which a square type playhouse is to be built.

Description of a triangular playhouse

101-104. Now I shall speak about the characteristics of the triangular (tryasra) type of playhouse (nāṭyamaṇḍapa). By the builders, a playhouse with three corners should be built, and the stage in it also should be made triangular. In one corner of the playhouse there should be a door, and a second door should be made at the back of the stage. Rules regarding walls and pillars[55] which hold good in case of a playhouse of the square type, will be applicable in case of the triangular type.[56] These are the rules according to which different types of playhouse are to be constructed by the learned. Next I shall describe to you the [propitiatory] Pūjā in this connexion.

Here ends Chapter II of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, which treats of the Characteristics of a Playhouse (nāṭyamaṇḍapa).

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

raṅga here means ‘the stage.’ It may also mean the auditorium as well as the spectators sitting there. See Kālidāsa; Śak. I. 4. 2.

[2]:

Except the cave (c. 200 B.C.) in the Ramgarh hill suspected by Th. Bloch (Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, 1903-4, pp. 123ff) to have been the remains of a theatre, there is no other evidence of the existence of a playhouse in ancient India. From the description of the playhouse in the present chapter we learn that it was constructed with brick walls and wooden posts probably with a thatched bungalow roof. The saṃgīdāsālā (saṃgītaśālā) mentioned by Kālidāsa in his Mālavi, was probably a playhouse. Large open halls called nāṭmandir often found in front of more recently built temples in Bengal and the neighbouring provinces may be connected with the extinct playhouse. This nāṭ-mandir or nāt-śālā is often met with in the medieval Bengali literature.

[3]:

Some are for identifying the oblong, the square and the triangular types respectively with the large, the middle-sized and the small playhouses, but Ag. very rightly objects to this. According to Ag.’s view there will be the following nine types of playhouse; (i) large oblong, (ii) large square, (iii) large triangular, (iv) medium oblong (v) medium square, (vi) medium triangular, (vii) small oblong, (viii) small square and (xi) small triangular. For a free translation of the passages in this chapter (8, 17, 19, 24-28, 33-35, 43-53, 63, 68, 69-92) relating to the construction of the playhouse see D.R. Mankad, “Hindu Theatre” in IHQ: VIII. 1932, pp. 482ff.

[4]:

They i.e., the large, the middle-sized and the small.

[5]:

As the measurements described are both in terms of cubits and daṇḍas (4 cubits), eighteen kinds of playhouse will be available.

[6]:

Ag. (I. p. 51) thinks that by gods, kings and other peoples mentioned in this passage, characters in a play have been meant. But this view does not seem to be plausible. So the other view, mentioned by him, which takes gods and kings etc. as spectators may be accepted.

[7]:

After this, B. reads three couplets which go rightly between 20 and 24. G. also holds the same view.

[8]:

The table of measurement given here agrees substantially with the one given by Kauṭilya (see IHQ. VIII. p, 482 footnote).

[9]:

A medium oblong playhouse is meant here. It is described in detail later on, See 33-38, 43-45, 63-65 below.

[10]:

See Ag. on this point.

[11]:

That is, mortals (men) should not build a playhouse of the biggest type which has been prescribed for gods.

[12]:

This hemistich is followed in B. and G. by one couplet which in trans, is as follows: The asterisms Uttaraphālgunī (Beta-Leonis), Uttarāṣāḍhā (Tau-Sagittarii). Uttarabhādrapadā (Andromedœ), Mṛgaśiras (Lambda-Orionis), Viśākhā (lota-Lībra). Revatī (Piseīum). Hastā (Corvii), Tiṣyā (Delta-Cancri) and Anurādhā (Delta-Scorpii) arc favourable in connexion with drama.

[13]:

svāminaḥ=paekṣāpateḥ, Ag.

[14]:

prayoktur-nāṭyācāryasya. (Ag.)

[15]:

tithi—a lunar day.

[16]:

karaṇa—a half of a lunar day, see below 43-45 note.

[17]:

See 17 above and the note 1 on it.

[18]:

dundubhi—a kind of drum.

[19]:

mṛdaṅga— a kind of earthen drum.

[20]:

paṇava—a small drum or tabor.

[21]:

pāṣaṇḍa—Derived originaly from pārṣada (meaning ‘assembly’ or ‘community’) its Pkt. form was pāsaḍa. With spontaneous nasalization of the second vowel it gave rise to Aśokan pasaṃda (Seventh Pillar Edict, Delhi-Topra), which is the basis of Skt. pāṣaṇḍa in the sense of ‘heretic.’

[22]:

B. reads śramiṇa, but G. śramaṇa; the word means naked Jain monks. See XVIII. 36 note 2.

[23]:

kāṣāya-vasana—men in kāṣāya or robe of dark red colour; such people being Buddhist monks who accepted the vow of celebacy, were considered an evil omen, for they symbolised unproductivity and want of wordly success etc. See also XVIII, 36 note 2.

[24]:

ghee—clarified butter.

[25]:

pāyasa—rice cooked in milk with sugar. It is a kind of rice-porridge.

[26]:

madhuparka—‘ a mixture of honey’; a respectful offering prescribed to be made in Vedic times, to an honourable person and this custom still lingers in ceremonies like marriage. Its ingredients are five: curd (dadhi), ghee (sarpis), water (jala), honey (kṣaudra) and white sugar (sitā).

[27]:

karaṇa—half of the lunar day (tithi). They are eleven in number viz.—(1) vava, (2) vālava, (3) kaulava. (4) taitila, (5) gara, (6) vaṇija, (7) viṣṭi, (8) śakuni, (9) cutuṣpada. (10) nāga and (11) kintughna, and of these the first seven and counted from the second half of the first day of the śukla-pakṣa (bright half of the moon) to the first half of the fourteenth day of the kṛṣṇa-pakṣa (dark half of the moon). They occur eight times in a month. The remaining karaṇas occur in the remaining duration of tithis and appear only once in a month. See Sūrya-siddhānta—II.67-68.

[28]:

Before 46, G. reads on the strength of a single ms. one couplet which seems to record a tradition that the pillars should be wooden.

[29]:

white—symbol of purity and learning associated with the Brahmins.

[30]:

red—symbol of energy and strength, associated with the Kṣatriyas.

[31]:

yellow—symbol of wealth (gold), associated with the Vaiśyas.

[32]:

dark—symbol of non-Aryan origin associated, with the Śūdras.

[33]:

This kind of payment is probably a relic of the time when here was no metallic currency.

[34]:

kṛsarā. is made of milk, sesamum (tila) and rice. Compare this word with NIA. khīcaḍi or khicūḍi (rice and pulse boiled together with a few spices.

[35]:

matta-vāraṇi—The word does not seem to occur in any Skt. dictionary. There is however a word mattavāraṇa meaning ‘a turret or small room on the top of a large building, a veranda, a pavilion.’ In Kṣīrasvāmīn’s commentary to the Amarakośa, mattvāraṇa has been explained as follows: mattālambopāśrayaḥ syāt prāgrīvo mattavāraṇaḥ (see Oka’s ed. p. 50). This is however not clear. Mattavīraṇayor varaṇḥaka mentioned in Subandhu’s Vāsavadattā (ed, Jivananda, p. 33) is probably connected with this word, Śivarāma Tripāṭhī’s commentery on this work does not give any clear idea about mattavāraṇa or mattavāraṇayor varaṇḍaka. But the word mattavārāṇī may be tentatively taken in the sense of ‘a side-room’. Ag. seems to have no clear idea about it. See also Ag. (I. pp. 64-65), A Dictionary of Hindu Architecture, by P. K. Acharya (Allahabad. 1927) dose not give us any light on this term.

[36]:

According to a view expressed in the Ag. (I. p. 62) the plinth of the mattavāraṇī is a cubit and a half higher than that of the stage. The plinth of the auditorium is also to be of the same height as that of the mattavāraṇī. But nothing has been said about the height of the plinth of the tiring room. From the use of terms like raṅgāvātaraṇa (descending into the stage) it might appear that the plinth of the tiring room too, was higher than the stage. Weber however considered that the stage was higher. Indische Studien, XIV. p, 225 Keith, Skt. Drama, p. 360 ; cf, Lévi, Le Théâtre indien, i. 374, ii. 52.

[37]:

According to one reading iron (āyasam) should be placed below them (pillars). But this is inconsistent, see 50-53 above.

[38]:

Some scholars following Ag. are in favour of taking rāṅgapīṭha and raṅgaśīrṣa as two different parts of the playhouse (see D. R. Mankad, “Hindu Theatre” in IHQ, VIII. 1932, pp. 480ff, and IX. 1933 pp. 973ff. ; V. Raghavan, “Theatre Architecture in Ancient India”, Triveni IV-VI, (1931, 1933) also “Hindu Theatre”. IHQ, IX. 1933. pp. 991. ff. I am unable to agree with them. For my arguments on this point see “The Hindu Theatre” in IHQ. IX. 1933 PP- PP- 591ff. and “The NŚ and the Abhinavabhārati” in IHQ. X. 1934pp. 161ff. see also note 3 on 86-92 below.

[39]:

On this point the Hindu Theatre has a similarity with the Chinese theatre. A. K. Coomaraswamy, “Hindu Theatre” in IHQ. IX. 1933. p 594.

[40]:

See note 1 on 68. If raṅgaśīrṣa and raṅgapīṭha are taken to mean two different parts of the playhouse, the interpretation of the passage will lead us to unnecessary difficulty.

[41]:

ūha and pratyūha may also be taken as two architectural terms (see Ag. I. p. 63).

[42]:

niryūha is evidently an architectural term, but it does not seem to have been explained clearly in any extant work. Ag’s explanation does not give us much light.

[43]:

In the absence of a more detailed description of the different parts of the wood-work, it is not possible to have a clear idea of them. Hence our knowledge of the passage remains incomplete till such a description is available in some authentic work.

[44]:

nāgadanta means ‘a bracket’. The word occurs in Vātsyāyana’s Kāmasūtra, I. 5.4).

[45]:

On this passage see Ag.

[46]:

The pillars of the playhouse being of wood, the roof was in all probability thatched, and in the forms of a pyramid with four sides. Probably that was to give it the semblance of a mountain cavern.

[47]:

The two floors mentioned here seem to refer to floors of different heights which the auditorium, mattavāraṇī and the stage have. See 63-65 above and note 2 on it According to some old commentators dvibhūmi indicated a two-storied playhouse while others were against such a suggestion, See Ag. (l. p. 65).

[48]:

kutapa—This word has been explained twice by Ag. as musical instruments. See (I. pp. 73 and 186). But in two other places (I. p, 65) and (I. p. 214) he explains it differently.

[49]:

ātmabhogajām literally means ‘due to self-indulgence or enjoyment of the self’, Compare with this description the decorative paintings in the Ajanta caves.

[50]:

Caturasra gives rise to NIA, cauras or coras.

[51]:

The exact nature of this division is not clear from the passage. The view expressed by Ag. (I, p. 66) on this point does not seem to be convincing.

[52]:

The position of these ten pillars and others mentioned afterwards is not clear from the text. Whatever is written on this point in Ag.’s commentary is equally difficult to understand. Those who are interested in the alleged view of Ag., may be referred to articles of D. R. Manked and V. Raghavan (loc. cit.). See also D. Subba Rao’s article in the Journal of the Oriental Inst. Baroda. vol II. pp. 190ff.

[53]:

śālastrī=śāla-bhañjikā (see A. K. Coomaraswamy, ‘The Women and tree or śālabhañjikā in Indian literature’, in Acta Orientalia, vol. VII., also cf. this author’s Yakṣas, Part II. p. 11.).

[54]:

Both the sides are meant. There should be two mattavāraṇīs as in the case of an oblong medium (vīkṛṣṭa-madhya) playhouse described before (17.32.-35).

[55]:

It is not clear how the triangular playhouse will have pillars like those of other types.

[56]:

No mattavāraṇī has been prescribed in case of the Triangular playhouse.