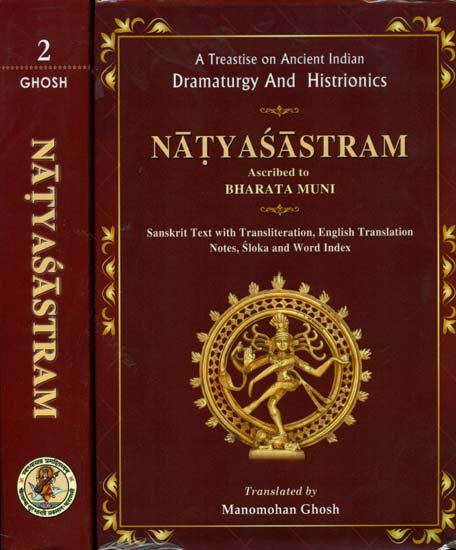

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Part 8 - The Date of the Nāṭyaśāstra

More than sixteen years ago, a careful investigation of the linguistic, metrical, geographical and ethnographic data, of the evidence to be drawn from the history of poetics and music, of the Kāmaśāstra and the Arthaśāstra, and from inscriptions the present writer came to the conclusion that the available text of the Nāṭyaśāstra existed in the second century after Christ, while the tradition which it recorded may go back to a period as early as 100B.C. (The Date of Bharata-Nāṭyaśāstra, in the JDL. Vol. XXV. 1934).[1] Since this conclusion was made, a more intensive study of the text as well as accession of fresh data has confirmed the writer’s belief in its soundness. These additional materials are being discussed below.

1. The Geographical Data

Geographical names occur in the Nāṭyaśāstra (XIV. 36ff.) mostly in connexion with pravṛttis or Local Usages which seem to be a later conception and not at all indispensable for understanding the theatrical art as explained in the Nāṭyaśāstra. In fact the authors of the Daśarūpa and the Nāṭakalakṣaṇa, who speak of the vṛttis are absolutely silent on pravṛttis which are connected with them. Considering the fact that these works depend a great deal on the Nāṭyaśāstra their omission of this item may be taken as very significant. Geographical names occuring in connexion with the pravṛttis are found in the Mbh. and some of the Purāṇas, some of these being almost in the same sequence (see D.C. Sircar, “Text of the Puranic Lists of Peoples” in IHQ. Vol. XXI., 1945, pp. 297-314). It seems that some interpolator put them into the text of the Nāṭyaśāstra, for associating it with all the different parts of India, though the original work was an exposition of the dramatic art as it was practised in the northern India especially in the midland only. Hence the geographical data should not bo used in determining the date of our text.

2. The Nāṭyaśāstra earlier than Kālidāsa

The argument that a particular dramatist who disregards any rule laid down in the Nāṭyaśāstra, will be earlier than it in time, will reverse the accepted chronological relation between the Nāṭyaśāstra and Kālidāsa.

(a) Though the fact has been overlooked by earlier writers on the subject, Kālidāsa too violates the rules of the Nāṭyaśāstra on the following points:

(i) Though the prescribed rule (XIX.33) is that the king’s wives should be given names connected with the idea of victory, some of Kālidāsa’s royal Heroines have been named as follows: Dhāriṇī, Īrāvatī (Mālavi.) Haṃsapadikā, Vasumatī (Śak.).

(ii) It is also in disregard of the rule (XIX.34) prescribing for the handmaids (preṣyā) the names of various flowers, that Kālidāsa has Nāgarikā, Madhukarikā, Samābhṛtikā, Nipuṇikā, Candrikā, Kaumudikā (Mālavi.), Parabhṛtikā, Caturikā (Śak.) as the names of handmaids in his play. Vakulāvalikā (Mālavi.) is possibly an exception.

(iii) Though the prescribed rule (XIX.34) is that the names having an idea of auspiciousness, should be given to the menials, Kālidāsa has Raivataka and Sārasaka (Mālavi.) as the names of servants.

(iv) The term svāmin has been used by an army-chief (senāpati) in addressing the king (Śak. II) in violation of the prescribed rule that it should he used for the crown-prince (XIX.12).

(v) Besides these, Kālidāsa has written elaborate Prologues to his plays, though the Nāṭyaśāstra does not recognize anything of this kind as a part of the play proper. These as well as the departures from the rules in Bhāsa’s play, may bo taken as great dramatists’ innovations which as creative geniuses they were fully entitled to.

(b) Besides these there seems to be other facts which probably go to show that Kālidāsa knew the present Nāṭyaśāstra. They are as follows:

(i) Kālidāsa uses the following technical terms of the Nāṭyaśāstra: aṅgahāra, vṛtti, sandhi, prayoga, (Kumāra, VII.91), aṅga-sattva-vacanā - śrayaṃ nṛttaṃ (Raghu, XIX. 36), pātra, prāśnika, sauṣṭhava, apadeśa, upavahana, śākhā, vastu, māyurī mārjanā (Mālavi.)

(ii) Kālidāsa mentions the mythical Bharata as the director of the celestial theatre (Vikram, III).

(iii) According to Kāṭayavema, Kālidāsa in his Mālāvi. (I.4.0; 21.0) refers to particular passages in the Nāṭyaśāstra (1.16-19; NŚ (C.) XXX, 92ff.)

3. The Mythological Data

In the paper mentioned in the beginning of this chapter the present writer was mistaken in his interpretation of the word mahāgrāmaṇī which does not mean Gaṇapati as Abhinava the reputed commentator of the Nāṭyaśāstra opines (see notes on III.1-8.). The absence from the Nāṭyaśāstra of this deity who does not appear in literature before the fourth century speaks indeed for the great antiquity of this work.

4. The Ethnological Data

The Nāṭyaśāstra in one passage (XXIII.99) names Kirātās, Barbaras and Pulindas together with Andhras, Dramilas, Kaśis and Kosalas who were brown (asita, lit. not white), and in another passage (XVIII.44) names Andhras and Dramilas together with Barbaras and Kirātas. Āpastamba the author of the Dharmasūtra who lived at the latest in the 800 B.C. belonged to the Andhra land (Jolly, Hindu Law and Custom, p. 6 and also P.V. Kane, Hist of the Dharmaśāstra. Vol. I. p, 45). Hence it may be assumed on the basis of these names that the Nāṭyaśāstra was in all likelihood composed at a time when a section at least of the Andhras and the Dramilas (forefathers of the modern Tamils) were still not looked upon as thoroughly civilized. Such a time may not have been much after the beginning of the Christian era.

5. The Epighraphical Data

Sylvain Lévi has discovered parallelism between the Nāṭyaśāstra and the inscriptions of the Indo-Scythian Ksatrapas like Chastana who are referred to therein as svāmi a term applicable, according to the Śāstra to the yuvarāja or crown-prince (I. Ant. Vol. XXXIII. pp. 163f). Though MM.P.V. Kano (Introduction to the SD. p. viii) has differed from him, Lévi’s argument does not seem to be without its force. It may not be considered unusual for common persons who are intimate with him to show the future king an exaggerated honour by calling him svāmin a term to be formally applied to the reigning monarch only. Besides the argument put forward by Lévi, there may be collected from the inscriptions other facts too which may incline us to take 200-300 A.C. as the time of the compilation of the Nāṭyaśāstra. These are as follows:

(a) The word gāndharva probably in the sense in which the Nāṭyaśāstra uses it (XXXVI.76) occurs in the Junagarh Rock inscription of Rudradaman, I (150 A.C.). This also mentions terms, like sauṣṭhava and niyuddha which we meet in the Nāṭyaśāstra probably in the same sense (Junagarh Inscription of Rudradaman I. See Select Inscriptions, pp. 172-173).

(b) The respect for ‘Cows and Brahmins’ (go-brāhmaṇa) which the author of the Nāṭyaśāstra shows at the end of his work (XXXVI.77) has its parallel in the inscription referred to above. And respect for Brahmins also finds expression in more than one inscription belonging to the 3rd century A.C. (op. cit, pp. 159, 161, 165)

(c) The three tribal names Śaka, Yavana, and Pahlava appearing in the inscription of Vasistiputra Pulomayi (149 A.C.) occur in the same order in the Nāṭyaśāstra (op. cit., p. 197,) and NŚ.

The cumulative effect of all these data seems to be that they may enable us to place the Nātyaśāstra about 200 A.C., the time of these inscriptions.

6. The Nāṭyaśāstra earlier than Bhāsa

Lack of conformity to the dramaturgic rules of the Nātyaśāstra has sometimes been cited as an evidence of the antiquity of Bhāsa, the argument being that as he wrote before the rules were formulated, he could not observe them. This view however, seems to be mistaken. For the rules occurring in the Nāṭyaśāstra cannot, for obvious reasons, be the author's fabrication without relation to any pre-existent literature.[2] If the Nāṭyaśāstra was written after Bhāsa’s plays, its rules had every chance of having been a generalisation from them as well as from numerous other dramatic works existing at the time, while the contrary being the case (i.e., Bhāsa being later than the Nāṭyaśāstra) some novelties are likely to be introduced by the dramatist in disregard of the existing rules. It is on this line of argument that the chronological relation between Bhāsa and the Nāṭyśāstra, will be judged below.

(a) On no less than three points, Bhāsa seems to have disregarded the rules of the Nāṭyaśāstra. These are as follows:

(i) The sūtradhāra (Director) begins the plays, though according to the Nāṭyaśāstra the sthāpaka (Introducer) should perform this function (V. 167).

(ii) In contravention of the rule of the Nāṭyaśāstra (XX.20) Bhāsa allows death in Act I of Abhiṣeka.

(iii) In the Madhyama-vyāyoga and the Dūtaghaṭotkaca, Bhāsa does not give the usual bharatavākaya (final benediction) and what he gives in its stead, may be an innovation.

Hence it may be assumed that the Nāṭyaśāstra was completed before the advent of Bhāsa.

(b) Besides this, there seems to be some good evidence in his works to show that the dramatist was acquainted with this ancient work on drama. For example, he mentions in a humorous context the Jester confounding the Nāṭyaśāstra (Avi. II 0. 38-39) with the Rāmāyaṇa. Bhāsa’s mention of some techinical terms as well as the acquaintance which he shows with some special rules of the Nāṭyaśāstra may also be said to strengthen the above assumption.

(i) First, about the technical terms. They are: sauṣṭhava, prastāvanā, sūtradhāra, prekṣaka, cārī, gati, bhadramukha, hāva, bhāva, māriṣa, nāṭakīyā, the root paṭha, raṅga.

(ii) The hetaera in the Cārudatta (I.26, 38.) says within herself, “I am unworthy of being allowed entrance into the harem” (abhāiṇī aham abbhantara-pavesassa). This seems to refer to the NŚ. XX.54. The expression, “by means of a Nāṭaka suiting the time” (kālasaṃvādiṇā nāḍaeṇa) in Pratimā. (I.4.7) probably points to NŚ. XXVII.88ff.

(iii) The vocal skill of the hetaera referred to by the Śakāra (Parasite) in the Cārudatta may also be said to point to the elaborate rules regarding intonation (kāku) in the NŚ. XIX.37-8.

(iv) Besides these, expressions like “the two feet made facile in dance due to training” (nṛttopadeśa-viśada-caraṇau) and “she represents the words with all her limbs” (abhinayati vacāṃsi sarvagātraiḥ) in the Cārudatta (I.9.0, 16.0) probably relate to the elaborate discussion on dance and the use of gestures in the Nāṭyaśāstra.

On the basis of all these it may be assumed that Bhāsa was acquainted with the contents of the present text of the Nāṭyaśāstra. Hence it may be placed in the 2nd centuary A.C. ie. one century before the time generally assigned to Bhāsa’s works. (Jolly, Introduction to AŚ. p. 10, but according to Konow Bhāsa’s date may bo the 2nd century A.C. See ID. p. 51).

From the foregoing discussions it may be reasonable to assume the existence of the Nāṭyaśāstra in the 2nd century A.C., though it must not be supposed that the work remained uninterfered with by interpolators of later ages. Such an interpolation may exist more or less in all the ancient texts. For example, Aristotle’s Poetics too, in its received text, has been suspected to have interpolated passages in it. There are indeed interpolated passages in the Nāṭyaśāstra and some of these have been pointed out[3] and a few more may by some chance be discovered afterwards. But this may not bring down the work as a whole to later times.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

For a bibliography on the Date of the NŚ. see this paper p. 1.

[2]:

F. Hall in his Introduction (p. 12) to the Daśarūpa says: At all events, he (Bharata).would hardly have elaborated them (the rules) except as inductions, from actual compositions.

[3]:

See notes on XVIII.6, 48; XX.63. Besides these cases, the seventeen couplets after XV.101 and the five couplets after XVI.169 are spurious. For these do not give any important information regarding the art of the theatre or dramaturgy and may be merely scholastic additions. The passage on pravṛttis XIV.36-55 may also bo spurious.