The Markandeya Purana

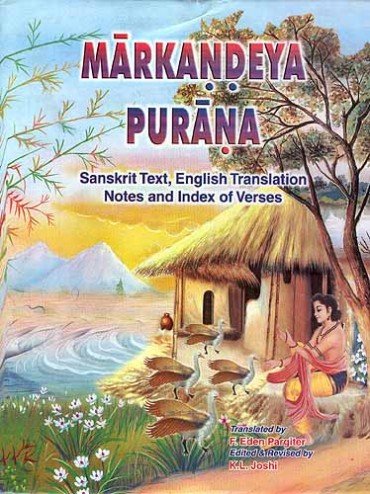

by Frederick Eden Pargiter | 1904 | 247,181 words | ISBN-10: 8171102237

This page relates “the description of the earth (continued)” which forms the 58th chapter of the English translation of the Markandeya-purana: an ancient Sanskrit text dealing with Indian history, philosophy and traditions. It consists of 137 parts narrated by sage (rishi) Markandeya: a well-known character in the ancient Puranas. Chapter 58 is included the section known as “exposition of the manvantaras”.

Canto LVIII - The description of the Earth (continued)

Mārkaṇḍeya continuing represents India as resting upon Viṣṇu in the form of a tortoise looking eastward, and distributes the various countries and peoples accordingly over the several parts of his body, together with the corresponding lunar constellations. He gives an astrological application to this arrangement and enjoins the performance of religious rites to avoid calamity. He also distributes the constellations of the Zodiac over the Tortoise’s body.

Krauṣṭuki[1] spoke:

Adorable Sir! Thou hast duly declared Bhārata to me, its rivers, mountains, countries, and the people who inhabit it. But thou didst previously make mention of the Tortoise, who is the adorable Viṣṇu, in Bhārata; I desire to hear fully about his position.

What position does he, the god Janārdana, occupy in his form of the Tortoise? And how are weal and woe indicated thereby to mankind according to the position of his face and of his feet? Expound all that about him.

Mārkaṇḍeya spoke:

With his face looking eastwards the adorable Tortoise-formed god takes bis position, when he approaches this nine-portioned country Bhārata, O brāhman. The constellations are arranged all about him in nine divisions, and the countries[2] also, O brāhman. Hear duly from me which they are.

The Vedamantras,[3] the Vimāṇḍavyas,[4] the Śālvas,[5] and the Nīpas,[6] and the Śakas,[7] and the Ujjihānas.[8] my child,[9] the Ghoṣasaṅkhyas,[10] and the Khaśas,[11] the Sārasvatas,[12] the Matsyas,[13] the Śūrasenas,[14] and the people of Mathurā,[15] the Dharmāraṇyas,[16] the Jyotiṣikas,[17] the Gauragrīvas,[18] the Guḍas[19] and the Aśmakas,[20] the Vaidehakas,[21] and the Pañcālas,[22] the Saṅketas,[23] the Kankas[24] and Mārutas,[25] the Kālakoṭisas,[26] and Pāṣaṇḍas,[27] and the inhabitants of the Pāripātra mountains,[28] the Kāpiṅgalas,[29] Kururvāliyas,[30] and the Uḍumbara people,[31] and the Gajāhvayas[32]—these are in the middle[33] of the Tortoise as he lies within the water.

To these people, who dwell in his middle, the three constellations, Kṛtlikā, Rohiṇī and Saumyā,[34] reveal[35] weal and woe, O brāhman.

The hills[36] Vṛṣadhvaja,[37] and Añjana,[38] Jambvākhya,[39] and Mānavācala,[40] Sūrpakarṇa,[41] Vyāghramukha,[42] Kharmaka.[43] and Karvaṭāśana;[44] these hills,[45] the people of Mīthilā,[46] the Śubhras,[47] and the Vadanadanturas,[48] and the Candreśvaras[49] also, and the Khaśas,[50] and the Magadhas,[51] the Prāgjyotiṣas,[52] and the Lauhityas,[53] the cannibals who dwell on the sea-coast;[54] the hills Pūrṇotkaṭa,[55] Bhadragaura,[56] and Udayagiri;[57] and the Kaśāyas,[58] the Mekhalāmuṣṭas,[59] the Tāmaliptas,[60] the Ekapādapas,[61] the Vardhamānas,[62] and the Kośalas[63] are situated in the Tortoise’s face.

The three constellations Raudra,[64] Punarvasu, and Puṣya are situated in its face.

Now these are the countries which are situated in the Tortoises right fore foot: listen while I mention them, O Krauṣṭuki.[65] The Kaliṅgas,[66] the Baṅgas,[67] and the Jaṭharas,[68] the Kośalas,[69] and the Mṛṣikas,[70] and the Cedis,[71] and the Ūrdhvakarṇas,[72] the Matsyas[73] and others who dwell on the Vindhya mountains,[74] the Vidarbhas,[75] and the Nārikelas[76], the Dharmadvīpas,[77] and the Elikas,[78] the Vyāghragrīvas,[79] the Mahāgrīvas,[80] the bearded Traipuras,[81] the Kaiṣindhyas,[82] and the Haimakūṭas,[83] the Niṣadhas,[84] the Kaṭakasthalas,[85] the Daśārṇas,[86] the naked Hārikas,[87] the Niṣādas,[88] the Kākulālakas,[89] and the Parṇaśavaras,[90]—these all are in the right fore foot.

The three constellations Aśleṣā, and Paitrya[91] and the First Phālguṇīs have their station in the right fore foot.

Laṅkā,[92] and the Kālājīnas,[93] the Śailikas,[94] and the Nikaṭas,[95] and those who inhabit the Mahendra[96] and Malaya[97] Mountains and the hill Durdura,[98] and those who dwell in the Karkoṭaka forest,[99] the Bhṛgu-kacchas,[100] and the Konkanas,[101] and the Sarvas,[102] and the Ābhīras[103] who dwell on the banks of the river Veṇī,[104] the Avantis,[105] the Dāsapuras,[106] and the Akaṇin[107] people, the Mahārāṣṭras,[108] and Karṇāṭas[109], the Gonarddhas,[110] Citrakūṭakas,[111] the Colas,[112] and the Kolagiras,[113] the people who wear matted hair[114] in Krauñcadvīpa,[115] the people who dwell by the Kāverī and on mount Ṛṣyamūka,[116] and those who are called Nāsikyas,[117] and those who wander by the borders of the Śaṅkha and Sukti[118] and other hills and of the Vaidūrya mountains,[119] and the Vāricaras,[120] the Kolas,[121] those who inhabit Carmapaṭṭa,[122] the Gaṇavāhyas,[123] the Paras,[124] those who have their dwellings in Kṛṣṇadvīpa,[125] and the peoples who live by the Sūrya hill[126] and the Kumuda hill,[127] the Aukhāvanas,[128] and the Piśikas,[129] and those who are called Karmanāyakas,[130] and those who are called the Southern Kauruṣas,[131] the Ṛṣikas,[132] the Tāpasāśramas,[133] the Ṛṣahhas,[134] and the Siṃhalas,[135] and those who inhabit Kāñcī,[136] the Tilaṅgas,[137] and the peoples who dwell in Kuñjaradarī[138] and Kaccha,[139] and Tāmraparṇī,[140]—such is the Tortoise’s right flank.

And the constellations, the Last Phālguṇīs, Hastā and Citrā are in the Tortoise’s right flank.

And next is the outer foot.[141] The Kāmbojas,[142] and Pahlavas,[143] and the Baḍavāmukhas,[144] and the Sindhus[145] and Sauvīras,[146] the Ānartas,[147] the Vanitāmukhas,[148] the Drāvaṇas,[149] the Sārgigas,[150] the Śūdras,[151] the Karṇaprādheyas[152] and Varvaras,[153] the Kirātas,[154] the Pāradas,[155] the Pāṇḍyas[156] and the Pāraśavas,[157] the Kalas,[158] the Dhūrtakas,[159] the Haimagirikas,[160] the Sindhukālakavairatas,[161] the Saurāṣṭras,[162] and the Daradas,[163] and the Drāviḍas,[164] the Mahārṇavas[165]—these peoples are situated in the right hind foot.

And the Svātīs,[166] Viśākhā and Maitra[167] are the three corresponding constellations.

The hills Maṇimegha,[168] and Kṣurādrī,[169] and Khañjana,[170] and Astagiri;[171] the Aparāntika people,[172] and Haihayas,[173] the Śāntikas,[174] Vipraśastakas,[175] the Kokankaṇas,[176] Pañcadakas,[177] the Vamanas,[178] and the Avaras,[179] the Tārakṣuras,[180] the Angatakas,[181] the Sarkaras,[182] the Śālmaveśmakas,[183] the Gurusvaras,[184] the Phalguṇakas,[185] and the people who dwell by the river Venumatī,[186] and the Phalgulukas,[187] the Ghoras,[188] and the Guruhas,[189] and the Kalas,[190] the Ekekṣanas,[191] the Vājikeśas,[192] the Dīrghagrīvas,[193] and the Cūlikas,[194] and the Aśvakeśas,[195] these peoples are situated in the Tortoise’s tail.

And so situated also are the three constellations Aindra,[196] Mūla, and Pūrvā Aṣādhā.

The Māṇḍavyas,[197] and Caṇḍakhāras,[198] and Aśvakālanatas,[199] and the Kunyatālaḍahas,[200] the Strīvāhyas,[201] and the Bālikas,[202] and the Nṛsiṃhas[203] who dwell on the Veṇumatī,[204] and the other people who dwell in Valāva,[205] and the Dharmabaddhas,[206] the Alūkas,[207] the people who occupy Urukarma[208]—these peoples are in the Tortoise’s left hind[209] foot.[210]

Where also Āṣāḍhā and Śravaṇā and Dhaniṣṭhā are situated.

The mountains Kailāsa,[211] and Himavat, Dhanuṣmat,[212] and Vasumat,[213] the Krauñcas,[214] and the Kurus[215] and Vakas,[216] and the people who are called Kṣudravīṇas,[217] the Rasālayas,[218] and the Kaikeyas,[219] the Bhogaprasthas,[220] and the Yāmunas,[221] the Antardvīpas,[222] and the Trigartas,[223] the Agnījyas,[224] the Sārdana peoples,[225] the Aśvamukhas[226] also, the Prāptas,[227] the long-haired Civiḍas,[228] the Dāserakas,[229] the Vāṭadhānas,[230] and the Śavadhānas,[231] the Puṣkalas,[232] and Adhama Kairātas,[233] and those who are settled in Takṣaśilā,[234] the Ambālas,[235] the Mālavas,[236] the Madras,[237] the Venukas,[238] and the Vadantikas,[239] the Piṅgalas,[240] the Mānakalahas,[241] the Hūṇas,[242] and the Kohalakas.[243] the Māṇḍavyas,[244] the Bhūtiyuvakas,[245] the Śātakas,[246] the Hematārakas,[247] the Yaśomatyas,[248] and the Gāndhāras,[249] the Kharasāgararāśis,[250] the Yaudheyas,[251] and the Dāsameyas,[252] the Rājanyas,[253] and the Śyāmakas,[254] and the Kṣemadhūrtas[255] have taken up their position in the Tortoise’s left flank.

And there is the constellation Vāruṇa,[256] there the two constellations of Prauṣṭhapadā[257].

And the kingdom of the Yenas[258] and Kinnaras,[259] the country Praśupāla,[260] and the country Kīcaka,[261] and the country of Kāśmīra,[262] and the people of Abhisāra,[263] the Davadas,[264] and the Tvaṅganas,[265] the Kulaṭas,[266] the Vanarāṣṭrakas,[267] the Sairiṣṭhas,[268] the Brahmapurakas,[269] and the Vanavāliyakas,[270] the Kirātas[271] and Kauśikas[272] and Ānandas,[273] the Pahlava[274] and Lolana[275] peoples, the Dārvādas,[276] and the Marakas,[277] and the Kuruṭas,[278] the Annadārakas,[279] the Ekapādas,[280] the Khaśas,[281] the Ghoṣas,[282] the Svargabhaumānavadyakas,[283] and the Hiṅgas,[284] and the Yavanas,[285] and those who are called Cīraprāvaraṇas,[286] the Trinetras,[287] and the Pauravas,[288] and the Gandharvas,[289] O brahman. These people are situated in the Tortoise’s north-east foot.

And the three constellations, the Revatīs,[290] Āśvidaivatya[291] and Yāmya,[292] are declared to he situated in that foot and tend to the complete development of actions,[293] O best of munis.

And these very constellations are situated in these places,[294] O brāhman. These places, which have been mentioned in order, undergo calamity[295] when these their constellations are occulted,[296] and gain ascendancy,[297] O brāhman,[298] along with the planets which are favourably situated. Of whichever constellation whichever planet is lord, both the constellation and the corresponding country are dominated by it;[299] at its ascendany[300] good fortune accrues to that country, O best of munis—Singly all countries are alike; fear or prosperity[301] comes to people according as either arises out of the particular constellation and planet, O brāhman. The thought, that mankind are in a common predicament with their own particular constellations when these are unfavourable, inspires fear. Along with the particular planets there arises from their occultations an unfavourable influence which discourages exertion. Likewise the development of the conditions may he favourable; and so when the planets are badly situated it tends to produce slight benefit to men and to themselves with the wise who are learned in geography.[302] When the particular planet is badly situated,[303] men even of sacred merit have fear for their goods or cattle-pen, their dependants, friends or children or wife. Now men of little merit feel fear in their souls, very sinful men feel it everywhere indeed, but the sinless never in a single place. Man experiences good or evil, which may arise from community of region, place and people, or which may arise from having a common king, or which may arise peculiarly from himself,[304] or which may arise from community of constellation and planet. And mutual preservation is produced by the non-malignity[305] of the planets; and loss of good is produced by the evil results which spring from these veryplanets, O lordly brāhman.

I have described to thee what is the position of the Tortoise among the constellations. But this community of countries is inauspicious and also auspicious. Therefore a wise man, knowing the constellation of his particular country and the peculation of the planets, should perform a propitiatory rite for himself and observe the popular rumours, O best of men. Bad impulses[306] both of the gods and of the Daityas and other demons descend from the sky upon the earth; they have been called by sacred writings “popular rumours”[307] in the world. So a wise man should perform that propitiatory rite; he should not discard the popular rumours. By reason of them the decay of corrupt traditional doctrine[308] befits men. Those rumours may effect the rise of good and the casting off of sins, also the forsaking of wisdom,[309] O brāhman; they cause the loss of goods and other property. Therefore a wise man, being devoted to propitiatory rites and taking an interest in the popular rumours, should have the popular rumours proclaimed and the propitiatory rites performed at the occultations of planets; and he should practise fastings devoid of malice, the praise-worthy laudation of funeral monuments and other objects of veneration, prayer, the ḥoma oblation, and liberality and ablution; he should eschew anger and other passions. And a learned man should be devoid of malice and shew benevolence towards all created things; he should discard evil speech and also outrageous words. And a man should perform the, worship of the planets at all occultations. Thus all terrible things which result from the planets and constellations are without exception pacified with regard to self-subdued men.

This Tortoise described by me in India is in truth the adorable lord Nārāyaṇa, whose soul is inconceivable, and in whom everything is established. In it all the gods have their station, each resorting to his own constellation. Thus, in its middle are Agni, the Earth, and the Moon, O bhrāhman. In its middle are Aries and the next two constellations;[310] in its mouth are Gemini and the next constellation; and in the south-east foot Cancer and Leo are situated; and in its side are placed the three signs of the zodiac, Leo, Virgo and Libra: and both Libra and Scorpio are in its Southwest foot; and at its hinder part[311] is stationed Sagittarius along with Scorpio; and in its north-west foot are the three signs Sagittarius and the next two; and Aquarius and Pisces have resorted to its northern side; Pisces and Aries are placed in its north-east foot, O brahman.

The countries are placed in the Tortoise, and the constellations in these countries, O brāhman, and the signs of the zodiac in the constellations, the planets in the signs of the zodiac.[312] Therefore one should indicate calamity to a country when its particular planets and constellations are occulted. In that event one should bathe and give alms and perform the homa oblation and the rest of the ritual.

This very foot of Viṣṇu, which is in the midst of the planets, is Brahmā.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

For Kroṣṭukir read Krauṣṭukir.

[2]:

The arrangement of the countries is very far from correct; and this canto cannot be compared with the last canto for accuracy. To make the shape of India conform to that of a Tortoise lying outspread and facing eastwards is an absurd fancy and a difficult problem.

[3]:

This is not in the dictionary and I have not found the name elsewhere. Does it mean “those who observe the Vedas and the Mantras especially” or has it any reference to Brahmāvarta?

[4]:

I have not found this elsewhere and it is not in the dictionary. Māṇḍavyas are mentioned in verse 38.

[5]:

Or Śālveyas as they were also called (Vana-P. cclxiii. 15576-82). The Śālvas are often mentioned in the MahāBhārata They were near the Kurus (Virāṭa-P. i. 11-12) and the Trigartas (id., xxx); and in the beautiful story of Satya-vat and Sāvitrī, he was a Śālva prince and she a Madra princess (Vana-P. ccxcii, &c.). Other indications of Śālva are given in the allusions to Kṛṣṇa’s conquest of it, but the story is marred because the people are called Daityas and Dānavas, and Saubha which seems to have been the capital is described as a city and as situated in the air, and also as able to move about freely (Vana-P. xiv-xxii; Udyoga-P. xlvii. 1886; and Droṇa-P. xi. 395). The Śālva king attacked Dvāra-vatī, and Kṛṣṇa in retaliation killed him and destroyed Saubha at the gulf of the sea (ibid.), which can be none other than the Rann of Kachh. From these indications it appears Śālva was the country along the western side of the Aravalli hills. Saubha is incapable of being determined. Śālva seems to have contained another city called Mārttikāvata (or Mṛttikā-vatī?), which is probably the same as the Mṛttikā-vatī mentioned in page 342, note † (Vana-P. xiv. 629; and xx. 791). The Hari-Vaṃsa says king Sagara degraded the Śālvas (xiv. 784), but this is a late fable for the Śālva king was one of the leading monarchs in Kṛṣṇa’s time (id, cviii. 6029), and was brother of Śiśu-pāla king of Cedi (Vana-P. xiv. 620-7); and other allusions shew that Śālva was a famous kingdom before that (Udyoga-P. clxxiii and clxxiv; and Anuśās.-P. cxxxvii. 6267); besides which, Satya-vat and Sāvitrī rank with the noblest characters in ancient Indian story. The weird legend of Yyushitāśva’s queen no doubt means her sons became Śālvas and did not originate the race (Ādi-P. cxxi. 4695-4714), as in the case of the Madras (page 315, note ‡).

[6]:

The Nīpas began with king Nīpa of the Paurava race, who established his dynasty in Kāmpilya, the capital of Southern Pāñcāla, about 12 or 15 generations anterior to the Pāṇḍavas; the dynasty flourished in king Brahma-datta who was contemporary with their fifth ancestor Pratīpa, and it was destroyed in Bhīṣma’s time (Hari-Vaṃśa, xx. 1060-73; M-Bh., Ādi-P. cxxxviii. 5512-3; and Matsya-P. xlix. 52 and 53) in the person of Janamejaya, nicknamed Durbuddhi, who after exterminating his kinsmen was himself killed by Ugrāyudha (Udyoga-P. lxxiii. 2729; Harivaṃśa, xx. 1071“2; and Matsya-P. xlix. 59). Kāmpilya is the modern Kampil on the old Ganges between Budaon and Farokhabad (Cunningham, Arch. Surv. Repts., I. 255). Priṣata, who is said to have been the last king’s grandson but was a Pāñcāla with a different ancestry, obtained the kingdom and handed down a new dynasty to his son Drupada (Hari-Vaṃśa, xx. 1082-1)15; and xxxii. 1778-93). The Nīpas who survived are mentioned in the MahāBhārata as an inferior people (Sabhā-P. xlix. 1804; and 1. 1844).

[7]:

The śakas were originally an outside race and are mentioned often in the M-Bh. They were considered to be mlecchas (Vana-P. clxxxviii. 12838-9), and were classed generally with Yavanas, but also with Kāmbojas, Pahlavas, Tukhāras and Khaśas (Sabhā-P. xxxi. 1199; 1. 1850; Udyoga-P. iii. 78; xviii. 590; Droṇa-P. xi. 399; xx. 798; cxxi. 4818; Śānti-P. lxv. 2429; and Vana-P. li. 1990; and also Rāmāy., Kiṣk. K. xliv. 13). Their home therefore lay to the north-west, and they are generally identified with the Scythians (Lat. Sacæ). They penetrated into India by invasions, and a branch is mentioned in the M-Bh. as in the Eastern region, apparently in Behar (Sabhā-P. xxix. 1088; and li. 1872; see also Rāmāy., Kiṣk. K. xl. 21). Buddha Śākya-muui is considered to have been of Śaka race. Their inroads continued through many centuries, and were resisted by various kings; and they are mentioned in the text as having established themselves in Madhya-deśa. The Harivaṃśa makes them the descendants of Nariṣya one of Manu Vaivasvata’s sons (x. 614 and 641); another account says they were Kṣattriyas and became degraded from having no brahmans (M-Bh., Anuśās.- P. xxxiii. 2103; and Mann x. 43-44). The Rāmāy. has an absurd fable about their creation (Ādi-K. lvi. 3; see page 314 note *).

[8]:

Ujjihāna is given in the dictionary as the name of a region, but have not met it anywhere. Perhaps it is to be identified with the town Urjihānā, which was situated south-east of Vārana-sthala, which is the same as Hāsti-napura, or near it (Rāmāy., Ayodh. K. lxxiii. 8-10); and in that direction there is now a town called Ujhani about 11 miles south-west of Budaon.

[9]:

Vatsa; but it would be better to read Vatsā, “the Vatsas;” seepage 307, note *.

[10]:

This is not in the dictionary and I have not found the name elsewhere. It may mean “those who are reckoned among Ghoṣas or herdsmen,” and be an adjective to Khaśas.

[11]:

Or Khasas. They were an outside people on the north, as mentioned in page 346 note *. In one passage they are placed between Meru and Mandara near the R. Śailodā (Sabhā-P. li. 1858-9), that is somewhere in Western Thibet; according to the Matsya Purāṇa the R. Śailodakā rises at Mt. Aruṇa which is west of Kailāsa and flows into the Western Sea (cxx. 19-23). Khaśa has been connected with Kaṣgar. The Khaśas also made inroads into India, for they are classed among the Pañjab nations in a passage in the M-Bh., which shews its later age by its tone (Karṇa-P. xliv. 2070), and they are mentioned in the text here as settled in Madhya-deśa. Manu says they were Kṣattriyas and became degraded by the loss of sacred rites and the absence of brahmans (x. 43-44).

[12]:

“Those who live along the Saras-vatī,” that is, the sacred river north of Kuru-kṣetra. They are not the same as the people named in canto lvii. verse 51.

[13]:

See page 307 note

[14]:

Śūrasena lay immediately south of Indra-prastha or Delhi (Sabhā-P., xxx. 1105-6), and comprised the country around Mathurā, the modern Mnttra (Hari-Vaṃśa, lv. 3093—3102; and xci. 4973) to the east of Matsya (Virāta-P., v. 144-5); and it extended apparently from the Chambal to about 50 miles north of Muttra (see Cunningham, Arch. Surv. Repts., XX. 2). The Śūrasenas belonged to the Yādava and Haihaya race, for Mathurā the capital is specially called the capital of the Yādavas, and the kings who reigned there belonged to that race (Hari-Vaṃśa, lvii. 3180-83; lxxix. 4124-34; xc.4904; cxiv. 6387; and xxxviii. 2024 and 2027). A king named Śūrasena, a son of Arjuna Kārtavīrya, is mentioned (id., xxxiv. 1892), who is, no doubt, intended as the eponymous ancestor of this people, for Arjuna who vanquished Rāvana was slightly anterior to Rāma, and the Harivaṃśa says Śūrasena occupied this country after Śatru-ghna’s time (id., lv. 3102); Bee next note. The Śūrasenas constituted a powerful kingdom shortly before the Pāṇḍavas’ time, and Kṛṣṇa killed Kaṃsa, who was one of the chief monarchs of that age, broke up the sovereignty and betook himself to Ānarta. In later times Śūrasena presumably regained importance, for it gave its name to Śaurasenī one of the chief Prakrits.

[15]:

Mathurā was the capital of Śūrasena as mentioned in the last note, and is the modern Muttra on the R. Jumna (Hari-Vaṃśa, lv. 3060—61). The Harivaṃśa Bays that Madhu, king of the Daityas and Dānavas, and his son Lavaṇa reigned at Madhu-pura and Madhu-vana (lv. 3061-3); and during Kama’s reign Śatru-ghna killed Lavaṇa, cut down Madhu-vana and built Mathurā on its site (lv. 3083-96; and xcv. 5243—7); and after the death of Kāma and his brothers Bhīma of the Yādava race according to one passage (id., xcv. 5243-7) took the city and established it in his own family; and Śūrasena (see the last note) according to another passage occupied the country around (id., lv. 3102). It is said Bhīma’s son Andhaka was reigning in Mathurā while Kuśa and Lava reigned in Ayodhyā (id., xcv. 5247-8). These passages seem to make a marked distinction between the population in the country and the dynasty in the city.

[16]:

Dharmāraṇya was the name of a wood near Gayā (Vana-P. lxxxiv. 8063-4; Anuśās.-P. xxv. 1744; and clxv. 7655; with Vana-P. lxxxvii. 8304-8).

[17]:

This is not in the dictionary and I have not found the name elsewhere; but Buchanan Hamilton says there was a class of brahmans in Behar, called Jausi, the vulgar pronunciation of Jyotiṣ (Vol. I. p. 156).

[18]:

These are stated in the dictionary as in the text to be a people in Madhya-deśa; but I have not met the name elsewhere. The word may however be an adjective, “yellow-necked,” and qualify Guḍas and Aśmakas which are joined together in a compound.

[19]:

These are stated in the dictionary as in the text to be a people in Madhya-deśa, but I have not found the name elsewhere. Probably it is to be connected with the country Gauda which Cunningham says was formerly the southern part of North Kosala, i.e. the southern portion of the tract between the Ghogra and Rapti rivers (Arch. Surv. Repts. I. 327). The town Gaur in the Maldah district in Behar, which was once the capital of the Bengal kingdom, is too far east to be admissible here.

[20]:

See page 336, note §.

[21]:

The people of Videha, see page 329, note †.

[22]:

Pañcāla or Pañcāla was a large country, comprising the territory on both banks of the Ganges, and bounded on the north by Sub-Himalayan tribes, on the east by the same tribes and Kosala, on the south by Śūrasena, the junction of the Jumna and Chambal, and Kānya-kubja (Ādi-P., cxxxviii. 6512-3 and Virāta-P,, v. 144), and on the west by the Kurus and Śūrasenas (Sabhā-P., xxviii. 1061; and Bhīṣma-P., ix. 346). The Pāñcālas originated in the descendants of Ajamīḍha by his wife Nīlī, though the MahāBhārata (Ādi-P., xciv. 3722-3) and Harivaṃśa (xxxii. 1776-80, with which agrees the Matsya Purāṇa, xlix. 43-4 and 1. 1-4) differ in the number and names of the descendants. These passages from the Harivaṃśa and Matsya Purāṇa date their rise about eight or nine generations prior to the Pāṇḍavas, and the passage from the MahāBhārata seems to point to a much earlier kingdom. The country being large was divided into two kingdoms, the Ganges being the dividing line (Ādi-P., cxxxviii. 5509-16); to the north was North Pañcāla or Ahi-cchatra, with its capital at Ahi-cchatrā, the modern Ahichhatr, 18 miles west of Bareilly and 7 north of Aonla (Cunningham, Arch. Surv. Repts., 1.255-7); and to the south was South Pañcāla, with its capital at Kāmpilya, the modern Kampil, on the old Ganges between Budaon and Fa (khabad (ibid. 2 55). The Sṛñjayas, or descendants of Sṛñjaya, who are often mentioned in the MahāBhārata (e.g., Ādi-P., cxxxviii. 5476; and Droṇa-P., xxi. 883, 895 and 915) appear to have reigned in North Pañcāla, and the Nīpas in South Pañcāla see page 350 note *); on the destruction of the latter, Pṛṣata of the former dynasty united the two kingdoms, but Droṇa conquered his son Drupada and re-established the two kingdoms, keeping North Pañcāla himself, and restoring the South to Drupada who then reigned in Kāmpilya and Mākandī (Ādi-P. cxxxviii; Harivaṃśa, xx. 1060-1115).

[23]:

Putting aside the Utsava-saṅketas (see page 319 note †), the only instance where I have met this name is in the MahāBhārata (Śānti-P., clxxiv. 6514) where it is introduced apparently as the name of a town; but there is nothing to indicate where it was, and it is not so given in the dictionary. Probably however the reading here and there should be Śāketa, that is, Ayodhyā and its people. Otherwise they are not mentioned in this group where they should be, and they can hardly be intended by the Kośalas in verse 14.

[24]:

These are mentioned in the MahāBhārata only as an outside race, along with the Tukhāras, Śakas, Pahlavas, &c. (Sabhā-P., 1. 1850; and Śānti-P., lxv. 2429) Their being mentioned here in the middle of India suggests that they must have invaded and settled there. It may be noticed also that Yudhiṣṭhira took the name Kanka during his disguised residence at Virāṭa’s Court (Virāṭa-P. vii. 224).

[25]:

I have met no people of this name elsewhere. Perhaps the reading should be Mālavas, the people of Maīwa (see page 341 note *); they are mentioned in verse 45 below, but their more appropriate position is here.

[26]:

I have not met this name elsewhere, but it may mean the people of Kāla-koṭī, which is mentioned in the MahāBhārata as a place of pilgrimage (Vana-P., xcv. 8513), and which appears from the context to be between the Ganges and the Bāhudā (the Ram-ganga or perhaps the Gurra east of it; see page 291 note §§). Koṭi-tīrtha mentioned in the Matsya Purāṇa (cv. 44) seems to be the same. Moreover Kāla-koṭī may be the same as Kāla-kūṭa, which is alluded to occasionally (Sabhā-P., xxv. 997; Udyoga-P., xviii. 596—601; and perhaps Ādi-P., cxix. 4637), and for which the second passage indicates a similar position.

[27]:

“Heretics;” applied to Jains and Buddhists. I have met with no people of this name.

[28]:

See page 286 note ‡.

[29]:

I have not met this name elsewhere. A river called Kapiñjalā is mentioned in the Bhīṣma-P. list (ix. 334), but without any data to identify it. Two other readings may be suggested Kāliṅgakas, i.e., Kaliṅgas (see page 316, note †); or better perhaps Kālañjaras, the inhabitants of Kaliñjar, an ancient and celebrated hill and fort 33 miles south of Banda in Bundelkhand; it is mentioned only as a tīrtha in the MahāBhārata (Vana-P., lxxxv. 8198—8200; lxxxvii. 8317; and Anuśās.-P., xxv. 1721-2).

[30]:

This reading appears to be wrong, but it is not easy to suggest another entirely satisfactory. It is clear, however, that the Kurus are one of the races meant. Vāhyas are said to be a people in the dictionary.

The Kurus occupied the country from the Śivis and Sub-Himalayan tribes on the north to Matsya, Śūrasena and South Pañcāla on the south, and between North Pañcāla on the east and Maru-bhūmi (the Rajputana desert) on the west. Their territory appears to have been divided into three parts, Kuru-kṣetra, the Kurus and Kuru-jāṅgala (Ādi-P., cix. 4337-40). Kuru-kṣetra, ‘the cultivated land of the Kurus,’ comprised the whole tract on the west of the Jumna and included the sacred region between the Saras-vatī and Dṛṣad-vatī (Vana-P., Ixxxiii. 5071-8 and7073-6; Rāmāy., Ayodh.-K., Ixx. 12; and Megha-D., i. 49-50); it is said to have obtained this name because it was raised to honour, pra-kṛṣṭa, by Kuru (Śalya-P., liv. 3009); the Harivaṃśa, in xxxii. 1800, inverts the course of history, and this explanation was afterwards confused and altered into that of his ploughing it (e.g., Matsya-P., 1.20-22). Kuru-jāṅgala, ‘the waste land of the Kurus,’ was the eastern part of their territory and appears to have comprised the tract between the Ganges and North Pañcāla (Rāmāy., Ayodh.-K., lxx. 11; and MahāBhārata, Sabhā-P., xix. 793-4). The middle region between the Ganges and Jumna seems to have been called simply the Kurus’ country. The capital was Hāstinapura (see note † below), and Khāṇḍava-prastha or Indra-prastha, the modern Delhi, was a second capital founded by the Pāṇḍavas (Ādi-P., ccvii. 7568-94), Kuru was the eleventh ancestor of the Pāṇḍavas (id., xciv. 3738-51; and xcv. 3791-3820; and Harivaṃśa, xxxii. 1799—1800).

[31]:

Udumbara is Kachh or Kutch according to Lassen (Ind. Alt., Map) and Cunningham (Arch. Surv. Repts, XIV. 115 and 135), and their identification may apply to the Audumbaras mentioned in Sabhā-P., li. 1869; but the Udumbaras here are placed in Madhya-deśa. I have not met with the name elsewhere and it is not in the dictionary. Certain descendants of Viśvā-mitra were called Audumbaras (Hari-Vaṃśa, xxvii. 1466); and there was a river Uḍumbarā-vatī in the South (id., clxviii. 9511).

[32]:

The people of Hāstina-pura or Hastinā-pura, the capital of the Kurus (see page 354 note ‖), which is situated on the old bed of the Ganges, 22 miles north-east of Meerut; lat. 29° 9′ N., long. 78° 3′ E. It is said to have been founded by king Hastin who was the fourth ancestor of Kuru (Ādi-P., xcv. 3787—92; and Harivaṃśa, xx. 1053-4); bat he is omitted from the genealogy in Ādi-P., xciv. 3714-39 and Harivaṃśa, xxxii. 1754-6 and 1795-9. By a play on the meaning of the word hastin, ‘elephant,’ the city was also called Hastina-pura (Aśrama-vās.-P., xvii. 508 and xxxvi. 1010), Gaja-pura (dict.), Gajāhvaya (Udyoga-P., clxxvi. 6071), Gaja-sāhvaya (Ādi-P., cxiii. 4441 and 4460), Nāga-pura (ibid., 4461-2), Nāgāhva (diet.), Nāga-sāhvaya (Ādi-P., cxxxi. 5146) Vāraṇāhvaya (Āśrama-vās.-P., xxxix. 1098), and Vārana-sāhvaya (diet.). It seems probable, however, that the derivation from ‘elephant’ is the real one, because of the numerous freely-coined synonyms with that meaning, and because there was another town Vāraṇāvata among the Kurus not far from Hāstina-pura (Ādi-P., cxiii, with the description of the Pāṇḍavas’ subsequent movements, cxlix.-cli., and clvi. 6084—7), and also a place called Vārana-sthala among the Kurus or North Pāñcālas (Rāmāy., Ayodh.-K., lxxiii. 8) which was perhaps the same as Hāstina-pura (see page 351, note *).

[33]:

Madhye in verse 7.

[34]:

This does not appear to be the name of any nakṣatra, but seems to mean Mṛga-śiras or Āgrahāyaṇī, which follows Ruhiṇī and precedes Ārdiā (verse 15 and note).

[35]:

Vi-pāṭaka; not in the dictionary.

[36]:

Girayo in verse 12; see note §§ below.

[37]:

I have not met with, this name anywhere else, and it is not in the dictionary as the name of a hill. Is it to be identified with Baidyanath, near Deogarh in the Santal Parganas, where there is said to be one of the twelve oldest liṅgas of Śiva (Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Deogarh)?

[38]:

This may be the mountain from which Sugrīva summoned his vassal monkeys (Rāmāy., Kiṣk.-K., xxxvii. 5), and also the mountain called Añjanābha, mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Anuśās.-P., clxv. 7658); but there are no data to identify it.

[39]:

Jambu-mat is given in the dictionary as the name of a mountain, but I have not met with either name elsewhere.

[40]:

This is mentioned in the dictionary, but I have not found it anywhere else.

[41]:

Or, no doubt, Śūrpa-karṇa, but I have not met with either as the name of a mountain, nor is it given in the dictionary.

[42]:

I have not met with this as the name of a mountain elsewhere, nor is it in the dictionary. On hill Udaya-giri near Bhubaneswar, about 20 miles south of Cuttack, are a number of rock-cut caves, and one is sculptured in the form of a tiger’s open mouth, and is known by the name Vyāghra-mukhay can this be the hill intended here? It would be somewhat out of place here, but the grouping in this canto is far from perfect.

[43]:

I have not found this name elsewhere, nor is it in the dictionary. Is it to be connected with the Kharak-pur hills in the south of the Monghyr District in Behar? A people called Karbukas are mentioned in the East in the Rāmāy. (Kiṣk. K. xl. 29).

[44]:

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not met with it elsewhere; but it is no doubt to be connected with the country or town Karvaṭā, which is mentioned in conjñnction with Tāmra-lipta and Suhma in the west of Bengal (Mahā-Bhārata, Sabhā-P., xxix. 1098-9). See Karbukas in the last note.

[45]:

The two lines of verse 12 must, it seems, be inverted, so as to bring the word girayo next to the- mountains named in verse 11: otherwise the word is meaningless.

[46]:

For Mithilā, see page 329 note †; bat the people ot Videha have been mentioned already in verse 8 as situated in Hadhya-deśa.

[47]:

I have not met this name elsewhere, nor is it in the dictionary ns the name of a people. Probably the reading should be Suhmas; see p. 327 note*. The Śumbhas (Rāmāy., Kiṣk.-K., xl. 25) are no doubt the same.

[48]:

This is in the dictionary as the name of a people, but I have not met with it elsewhere. It may mean “showing their long teeth when speaking;” but here it is no doubt the name of a people as stated in the dictionary.

[49]:

I have not found this elsewhere nor is it in the dictionary as the name of a people. A people called Candra-vatsas are mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Udyoga-P., lxxiii. 2732).

[50]:

See page 346 note * and page 351 note §. Here a branch of these people is placed in the East of India.

[51]:

See page 330 note ‡.

[52]:

See page 328 note †.

[53]:

The people of Lauhitya (Mahā-Bhārata, Sabhā-P., xxix. 1100; and li. 1864) which was the country on the banks of the R. Lohita, or Lauhitya (Sabhā-P., ix. 374; Rāmāy., Kiṣk.-K., xl. 26; and Raghu-V., iv. 81) or Lohityā (Bhīṣma-P., ix. 343), and probably also Lohita-ganga (Hari-Vaṃśa, cxxii. 6873—6), the modern Brahma-putra. The mention of Lohita in Sabhā-P., xxvi. 1025 and Lauhitya in Anuśās.-P., xxv. 1732 appears to have a different application; and a place Lohitya is mentioned in Rāmāy, Ayodh.-K., lxxiii. 13, as situated between the Ganges and Go-matī. Viśvāmitra had certain descendants called Lohitas (Hari-Vaṃśa, xxvii. 1465) or Lauhitas (id., xxxii. 1771) who may have been the children of his grandson Lauhi (id., xxvii. 1474).

[54]:

Sāmudrāḥ puruṣādakāḥ; that is, on the coast of the Bay of Bengal which was the Eastern Ocean. They are mentioned in the Rāmāy. (Kiṣk.-K., xl(xi?). 30).

[55]:

This is mentioned in the dictionary, but I have not found it elsewhere.

[56]:

This is in the dictionary, but I have not found it elsewhere.

[57]:

There are several hills of this name; that intended here is no doubt the hill near Rāja-gṛha, or Rajgir. Its ancient name Cunningham says was Ṛṣi-giri (Arch. Surv. Repts., I. 21 and plate iii), which is mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Sabhā-P., xx. 798-800).

[58]:

This is not in the dictionary and I have not found it elsewhere. The proper reading is probably Kāśayo, “the Kāśis,” the people of Benares (see page 308 note †). They are a little out of place here, and should fall within the former group (verses 6-9), but are not mentioned there, and therefore come in here probably, for the grouping in this canto is far from perfect.

[59]:

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not found it elsewhere. The first part of the word is no doubt a mistake for Mekala or Mekalā, for the Mekalas and Mekala hills are not mentioned in any other group in this canto and may be intended here, though considerably out of their proper position (see page 341 note ‡). There was also a town or river called Mekalā, which (if a river) was distinct from the Narmadā; but it appears to have been more on the western side (Hari-Vaṃśa, xxxvii. 1983) and therefore less admissible in this passage. I would suggest that the second part of the word should be Puṇḍrās, “the Puṇḍras” (see page 329 note *). The text Mekhalā-muṣṭās however might mean “those who have been robbed of the triple zone” worn by the first three classes (see Manu, ii. 42) and might then be an adjective qualifying Kaśāyas.

[60]:

Or Tāmra-liptakas; see page 330 note *.

[61]:

“People who have only one tree;” but perhaps the reading should be Eka-pādakās, “people who have only one foot”? It was a common belief that such people existed, see MahāBhārata, Sabhā-P, 1. 1838 (where they are placed in the South) and Pliny, vii. 2; audit lasted down to modern times, see Mandeville’s Travels, chap. XIV. See Eka-pādas in verse 51.

[62]:

The people of Vardhamāna, the modern Bardhwan (commonly Burdwan) in West Bengal. It is not mentioned in the Rāmāy., nor MahāBhārata, but is a comparatively old town.

[63]:

This can hardly refer to Kosala, or Oudh (see page 308 note ‡) for, if so, this people would have been placed along with the people of Mithilā and Magadha in verse 12; whereas here the Kosalas are separated off from those nations by the insertion of three hills in verse 13, and are grouped with the Mekhalāmuṣṭas, Tāmra-liptas and Vardhamānas. Kosala here must therefore mean Dakṣiṇa Kosala which is mentioned in canto lvii, verse 54, as lying on the slope of the Vīndhya mountains (see page 342 note ¶), and especially the north and east portions of it, for the southern part is placed appropriately in the right fore foot in verse 16.

[64]:

This appears incorrect. Read Raudrī (fem.). a name for the constellation Ārdrā.

[65]:

For Kroṣṭuke read Krauṣṭuke.

[66]:

See page 334 note *.

[67]:

See page 326 note *.

[68]:

They are mentioned in the Bhīṣma-P. list (ix. 350) but with no data to identify their territory. Here they are joined in one compound with Kaliṅgas and Baṅgas.

[69]:

The people of Dakṣiṇa or Southern Kosala; see page 342 note ¶; the south portion is especially meant, see verse 14.

[70]:

See page 332 note †.

[71]:

There is no mention of a people called Cedis in the Eastern region in the older poems; but Cunningham repeatedly places a Cedi race in Chhattisgarh (Arch. Surv. Repts., IX. 54-57; and XVII. 24), yen in ancient times it was not so. Cedi was then one of the countries near the Kurus (Mahā-Bhārata, Virāta-P., i. 11-12; Udyoga-P., lxxi. 2594-5). It is placed in the Eastern region in the account of Bhīma’s conquests there (Sabhā-P., xxviii. 1069-74) and also in the South region in the description of Arjuna’s following the sacrificial horse (Āśva-medh.-P., lxxxiii. 2466-9); and it is also mentioned along with the Daśārṇas (see page 342 note †) and Pulindas (see page 335 note †) in the former passage. Cedi bordered on the Jumua, for king Vasa when hunting in a forest sent a message home to his queen across that river, and the forest could not have been far from his territory (Ādi-P., lxiii. 2373—87). Cedi, moreover, is often linked with Matsya and Karūṣa (e.g., Bhīṣma-P., ix. 348; liv. 2242; and Karṇa-P., xxx. 1231; see page 307 note * and page 341 note †), and with Kāśi and Karūṣa (e.g., Ādi-P., cxxiii. 4796; and Bhīṣma-P., cxvii. 5446). It was closely associated with Matsya and must have touched it, for an ancient king Sahaja reigned over both (Udyoga-P, lxxiii. 2732); and it seems probable that king Vasu’s son Matsya became king of Matsya (Ādi-P., lxiii. 2371-93; and Hari-V-, xxxii. 1804-6). From these indications it appears Cedi comprised the country south of the Jumna, from the R. Chambal on the north-west to near Citra-kūta on the south-east; and on the south it was bounded by the plateau of Malwa and the hills of Bundelkhand.

Its capital was Śukti-matī or Śukti-sāhvayā, (Vana-P., xxii. 898; and Āśva-medh.-P., lxxxiii- 2466-7) and was situated on the R. Śukti-matī, which is said to break through the Kolāhala hills (Ādi-P., lxiii. 2367-70; see page 286 note §). This river rises in the Vindhya Range, and must be east of the R. Daśārṇā, which is the most westerly river that rises in that range (compare notes † and ‡ on page 286); it is probably the modern R. Ken, for which I have found no Sanskrit name. Hence the Kolāhala hills were probably those between Panna and Bijawar in Bandelkhand, and the capital Śakti-matī was probably near the modern town Banda. The kingdom of Cedi seems to have been founded as an offshoot by the Yādavas of Vidarbha (Matsya-Purāṇa, xliii. 4-7; and xliv. 14 and 28-38); and after it had lasted through some 20 or 25 reigns, Vasu Uparicara, who was a Kaurava of the Paurava race, invaded it from the north some nine generations anterior to the Paṇḍavas, and conquering it established his own dynasty in it (id, l. 20-50), which lasted till after their time. For a fall discussion see Journal, Bengal As. Socy., 1895, Part I, p. 219.

[72]:

“Those who have erect ears;” bat I have not met this name elsewhere, and it is not, probably, the name of any people.

[73]:

This seems wholly out of place here: see page 307 note *.

[74]:

These mountains are also out of place here; they die away in Behar, that is, in the region occupied by the Tortoise’s head.

[75]:

These are absolutely out of place here; see page 335 note §.

[76]:

Nārikela is given in the dictionary as the name of an island, bat I have not met with any people of any such name elsewhere.

[77]:

I have not met with this name any where else.

[78]:

Or Ailikas. Neither name is in the dictionary, and I have not found them elsewhere. A river Elā is mentioned as situated in the Dekhan (Hari-V., clxviii. 9512), but without data to identify it.

[79]:

“Having necks like tigers”; perhaps an epithet to Traipuras.

[80]:

“Large-necked”; perhaps also an epithet to Traipuras.

[81]:

The people of Tripura, see page 313 note *; but they are quite out of place here.

[82]:

These seem to be the same as the Kiskindhakas; see page 312 note §.

[83]:

The people of Hema-kūṭa. I have found mention of only one Hema-kūṭa: it was a mountain or group of mountains in the Himalayas in the western part of Nepal (Mahā-Bhārata, Vana.-P., cx. 9968-87); but that does not seem appropriate here.

[84]:

See page 343 note ¶. These people are altogether out of place here.

[85]:

The people of Kaṭaka, the modern Cuttack in Orissa. This is a modern name and is mentioned in the Daśa-kumāra-carita (Story of Soma-datta). The name given to it by the Brahmans was Vārāṇasī in emulation with Benares.

[86]:

See page 342 note †. These people are altogether out place here.

[87]:

This name is not in the dictionary and I have not found it elsewhere.

[88]:

The Niṣādas were an aboriginal race and are described as very black, dwarfish and short-limbed, with large mouth, jaws and ears, with pendent nose, red eyes and copper coloured hair, and with a protuberant belly. Their name is fancifully derived from the command niṣīda, “sit down,” given to the first of them who was created. (Hari-Vaṃśa, v. 306-10; and Muir’s Sansk. Texts, II. 428.) They were specially a forest people, and were scattered all over Northern and Central India. The earliest references shew, they occupied the forest tracts throughout North India. In Kama’s time they held the country all around Prayāga and apparently southwards also (Journal, R. A. S., 1895, page 237); but in the Pāṇḍavas’ time they occupied the high lands of Mālwa and Central India (Mahā-Bhārata, Sabhā-P., xxix. 1085; xxx. 1109 and 1170; and Āśvamedh.-P., lxxxiii. 2472-5) and still formed a kingdom (Udyoga-P., iii. 84; and xlvii. 1881). It would seem that, as the Aryans extended their conquests, the Niṣādas were partly driven back into the hills and forests of Central India, and were partly subjugated and absorbed among the lowest classes of the population as appears from casual allusions (Rāmāy., Ādi-K., ii. 12; and MahāBhārata, Ādi-P., cxlviii; and Vana-P., cxxx. 10538-9). They are also mentioned as being pearl-divers and seamen in an island which seems to be on the west coast (Hari-Vaṃśa, xcv. 5214 and 5233-9). They were looked upon as very degraded in later times, but at first their position was not despicable, for Rāma and Guha king of the Niṣādas met as friends on equal terms (Ayodh.-K., xlvi. 20; xlvii. 9-12; and xcii. 3); and it seems Kṛṣṇa’s aunt Śruta-devā married the king of the Niṣādas (Hari-Vaṃśa, xxxv. 1930 and 1937-8).

[89]:

I have not found this name elsewhere, nor is it in the dictionary. Perhaps it is to be connected with Śrī-kākula, the modern Sreewacolum, a town 19 miles west of Masulipatam. It was founded by king Sumati of the Śāta-vāhanas or Andhras, and was their first capital (Arch. Surv. of S. India by R. Sewell, I. 55; and Report on Amarāvati, pp. 3 and 4).

[90]:

These were a tribe of Śavaras (see page 335 note *) who lived upon leaves; hence their name according to the dictionary; but a forest tribe would hardly live solely on leaves. Might it not more properly mean “the Śavaras who wear leaves”? A girdle of leaves was the ordinary clothing of most of the aboriginal tribes; see Dalton’s Ethnology, passim. They appear to be the modern Pāns, a very low aboriginal caste, common in Orissa and the Eastern Circars.

[91]:

This must mean Maghā, which comes between Aśleṣā and Pūrva-Phalguṇī—a meaning not in the dictionary.

[92]:

Rāvaṇa’s capital in Ceylon.

[93]:

This is given in the dictionary as the name of a people and analysed thus— kāla-ajīna, “those who wear black antelope skins;” but I have not found the name elsewhere.

[94]:

Perhaps the same as the Śailūṣas in canto lvii, verse 46.

[95]:

This name is not in the dictionary, and I have not met it elsewhere.

[96]:

See page 284, note †† and page 305, note §; yet these may be the mountains at C. Comorin, see Journal, R. A. S. 1894, p. 261.

[97]:

See page 285 note *.

[98]:

See page 287 note †.

[99]:

Karkoṭaka was the name of the Nāga king whom Nala saved from a forest fire (Mahā-Bhārata, Vana-P., lxvi); Where that happened is not clear, but probably it was somewhere in the middle or eastern part of the Satpura range (see page 343 note ¶); can that region be intended here? Karkoṭaka is also stated in the dictionary to be the name of a barbarous tribe of low origin, but I have not met with them elsewhere. Perhaps this word, however, may be connected with the modern Karād, a town in the Satara District, near which are many Buddhist caves. Its ancient name was Karahākaḍa or Karahākaṭa according to inscriptions (Arch. Surv. of W. India by J. Burgess, Memo. No. 10, page 16, and Cunningham’s Stupa of Bharhut pp. 131, 135 and 136), and it seems to be the same as Karahāṭaka mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Sabhā-P., xxx. 1173) and spoken of there as heretical, pāṣaṇḍa, no doubt because it was a Buddhist sanctuary as evidenced by its caves. See also Matsya P. xliii. 29 about Karkoṭaka.

See page 339 note **.

Or, more correctly, Konkaṇas. They are the inhabitants of the modem Konkan, the Marāthi-speaking lowland strip between the Western Ghats and the sea, from about Bombay southward to Goa. The Harivaṃśa says king Sagara degraded these people (xiv. 784).

These people are not mentioned in the dictionary and I have not met with them elsewhere. Perhaps the reading should be the Sarpas, i.e., “the Nāgas,” or the Śaravas who are named in MahāBhārata (Bhīṣma-P., 1. 2084, unless this be a mistake for Śavaras.)

See page 312 note †.

This is no doubt the same as Veṇyā, the name of two rivers in the Dekhan; see canto lvii, verses 24 and 26. Either river is admissible in this passage, but the Wain-ganga is meant more probably, because it flows through territory occupied by aboriginal tribes.

See page 340 note § and page 344 note §.

Or, better, Dāśa-puras, the people of Daśa-pura. This was the capital of king Ranti-deva (Megha-D., I. 46-48), and seems from the context there to have been situated on or near the R. Chambal in its lower portion. But the two accounts of Ranti-deva (Mahā-Bhārata, Droṇa-P., lxvii; and Śānti-P., xxix. 1013—22) describe him as exercising boundless hospitality chiefly with animal food, and fancifully explain the origin of the river, Carmaṇ-vatī, as the juices from the piles of the hides of the slaughtered animals; this suggests that he reigned along the upper portion of the river.

Or Ākaṇin. Neither is in the dictionary, and I have not found them elsewhere.

See page 333 note †.

The Canarese. Karṇāṭa properly comprises the south-west portion of the Nizam’s Dominions, and all the country west of that as far as the Western Ghats, and south of that as far as the Nilgiris. It did not include any part of the country below the Ghats, but its application has been greatly distorted by the Mohammedans and English. The name is probably derived from two Dravidian words meaning “black country,” because of the “black cotton-soil” of the plateau of the Southern Dekhan (Caldwell, Grammar of the Dravidian Languages, 34 and 35; and Hunter’s Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Karnātik). The Karṇātakas are mentioned in the Bhīṣma-P. list (ix. 366).

Go-narda is given in the dictionary as the name of a people in the Dekhan, but I have not found either form elsewhere. Goa is said to have had a large number of names in ancient times; but this does not appear to have been one of them (Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Goa).

The people of Citra-kūṭa; it appears to have been the range of hills (comprising the modern mount Citrakut) extending from south of Allahabad to about Panna near the R. Ken (see Journal, R. A. S., 1894, p. 239); but these people are very much out of place here.

See page 331 note ¶.

This name does not seem to be connected with the Kolas who are mentioned in verse 25. The Kolagiras are no doubt the same as the Kolvagireyas, who are placed in South India in the description of Arjuna’s following the sacrificial horse (Āśva-medh.-P., lxxxiii. 2475-7); and they would presumably be the inhabitants of Kolagiri, which is placed in South India in the account of Sahadeva’s conquests there, and which appears to have been an extensive region for the whole of it is spoken of (Sabhā-P., xxx. 1171). Kolagiri may mean “the hills belonging to the Kols,” but the Kols seem to be intended by the Kolas in verse 25. Kolagira may be compared with Kodagu, the ancient name of Coorg, which means ‘steep mountains’ (Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Coorg), and might therefore have led to the modification of the final part of the name to agree with the Sanskrit giri; but see page 366 note ‡. The name Kolagira somewhat resembles the Golāṅgulas of canto Ivii, verse 45; and Golāṅgula might be a corruption of Kodungdlūr, which is the modern town Craṅganore, 18 miles north of Cochin. It had a good harbour in early times, and was a capital town in the 4th century A.D. Syrian Christians were established there before the 9th century, and the Jews had a settlement there which was probably still earlier. It is considered of great sanctity by both Christians and Hindus (imp. Gaz, of India, Art. Ko-dungalūr).

Jaṭā-dhara; the dictionary gives it as a proper name. Jaṭā also means “long tresses of hair twisted or braided together, and coiled in a knot over the head so as to project like a horn from the forehead, or at other times allowed to fall carelessly over the back and shoulders.”

This was no doubt the county of which Krauñca-pura was the capital, for dvīpa appears to have had the meaning of “land enclosed between two rivers,” the modern doab; cf. Śākala-dvīpa, the doab in which Śākala (see page 315 note ‡) was situated, and the Seven dvīpas all in North India (Sabhā-P., xxv. 998-9). The Harivaṃśa says Sārasa, one of Yadu’s sons, founded Krauñca-pura in the South region in a district where the soil was copper-coloured and champaka and aśoka trees abounded, and his country was known as Vana-vāsi or Vana-vāsin (xcv. 5213 and 5231-3); and also that that town was near the Sahya Mts., and was situated apparently south of a river Khaṭvāṅgī and north of Gomanta bill (xcvi. 5325-40). If Gomanta was the modern Goa, these indications agree fairly well with the Krauñcālaya forest mentioned in the Rāmāy. (Araṇ.-K., lxxiv. 7), which appears to have been situated between the Godavari and Bhima rivers (Journal, R. A. S., 1894, page 250). But the town Bana-vāsi or Banawāsi, which was a city of note in early times, is in the North Kanara district, on the R. Warda (tributary of the Tuṅgabhadra), 14 miles from Sirsi in lat. 14° 33′ N., long. 75° 5′ E. (Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Banavasi; Arch. Surv. of W. India, No. 10, pp. 60 note and 100); and this is south of Goa. This was the country of the Vana-vāsakas (seo page 333 note *).

See page 289 note ‡.

These are, no doubt, the people of Nasik; see page 339 note ‖.

The text is Śaṅkha-sukty-ādi-vaidūrya-śaila, which may be so rendered as to make Śaṅkha and Sukti two of the hills which compose the Vaidūrya chain. I have not met with them elsewhere, and neither is in the dictionary as the name of a hill. Sukti can hardly be an error for the Śukti-mat range (see page 306 note §).

This is the Satpura range, for the Pāṇḍavas in their pilgrimage went from Vidarbha and the R. Payoṣṇī (the Purna and Taptī, see page 299 note †), across these mountains, to the R. Narmadā (Vana-P., cxx. and cxxi). This range was placed in the Southern region (ibid., lxxxviii. 8343), and also apparently, as Taidūrya-śikara, in the Western region (ibid., lxxxix. 8359-61); and in the former of these two passages it is called maṇi-maya.

I have not found this name elsewhere, nor is it in the dictionary.

See page 331 note ¶, but the passages cited there with reference to this people appear to refer to the Kolagiras; see page 363 note ‡‡. The Kols are a collection of aboriginal tribes, who are said to have dwelt in Behar in ancient times, but who now inhabit the mountainous districts and plateaux of Chutia Nagpur and are to be found to a smaller extent in the Tributary States of Orissa and in some districts of the Central Provinces (Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Kol).

This is not in the dictionary and I have not met it elsewhere. Is it to be identified with Salem in Madras?

I have not met this elsewhere. Does it refer to the Ganapati dynasty which flourished on the eastern coast during the 13th cent A.D.?

This is not in the dictionary and I have not found it elsewhere.

I have not met this name elsewhere, but it obviously refers to the R. Kṛṣṇa or Kistna, and probably means one of the doabs (see page 364 note †) beside that river, either between the Kistna and Bhīma or between the Kistna and Tuṅgabhadra.

I have not met this name elsewhere.

I have not found this name elsewhere. Comparing the various readings, it seems to have some connexion with the Kusumas of canto lvii verse 46; see page 332 note ‡.

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not found it elsewhere. Perhaps it is to be connected with the Okhalakiyas mentioned in Arch. Surv. of W. India, no. 10, pp. 34-35.

Or as the text may be read, Sapiśikas. Piśika is in the dictionary, but I have not met with either name elsewhere.

I have not found this name elsewhere and it is not in the dictionary. Perhaps the reading should be Kambu-nāyakas or Kombu-nāyakas, and mean the people of Coorg. “According to tradition, Goorg was at this period (16th century A.D.?) divided into 12 kombus or districts, each ruled by an independent chieftain, called a nāyak” (Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Coorg). The similarity of the names is very remarkable.

This name is not in the dictionary and I have not met with it elsewhere Perhaps it should be Kāruṣas (see page 341 note †), and the people intended are a southern branch of that nation.

These are the people mentioned in the Rāmāy. (Kiṣk.-K., xli. 16) and MahāBhārata (Karṇa-P., viii. 237) and Harivaṃśa (cxix. 6724-6). There was also a river called the Ṛṣkā (Mahā-Bhārata, Vana-P., xii. 493) which may be connected with the same people. I have found no further data for fixing their position. See page 332 note †; the Mūṣikas mentioned there may perhaps be the people dwelling on the E. Musi, the tributary of the Kistna on which Haidarabad stands (Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Kistna).

I have not met this name elsewhere nor is it in the dictionary. Perhaps it refers to the descendants of ascetics, see page 339 note †.

These are, no doubt, the inhabitants of Ṛṣabha-parvata mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Vana-P., lxxxv. 8163-4) and placed there between Śrī-parvata and the Kāverī. Śrī-parvata is on the Kistna in the Karnul district (see page 290, note ‡). The Ṛṣabha hills are therefore probably the southern portion of the Eastern Ghats, but none of the ranges there appears to have any name resembling this.

The people of Ceylon. They are named in the MahāBhārata; it is said the Siṃhala king attended Yudhiṣṭhira’s Rāja-sūya sacrifice (Sabhā-P., xxxiii. 1271; and Vana-P., li. 1989); and the Siṃhalas brought to him presents of lapis lazuli, which is the essence of the sea (samudra-sāra), and abundance of pearls and elephants’ housings (Sabhā-P., li. 1893-4). They are also named as fighting on the Kauravas’ side in the great war (Droṇa-P., xx. 798). This name is not I believe given to Ceylon in the Rāmāy., but the name Siṃhikā is given to a terrible female Rākṣasa who dwelt in the middle of the sea between India and Ceylon, and whom Hanūmān killed as he leapt across to the island (Kiṣk.-K, xli. 38; and Sund.-K., viii. 5-13).

This is Kāñcī-puram or Kāñcī-varam, the modem Conjevaram, about 37 miles south-west of Madras. It is not, I believe, mentioned in the Rāmāy. or MahāBhārata, unless the Kāñcyas who are named as fighting in the great war (Karṇa-P., xii. 459) are the people of this town, but the proper reading there should probably be Kāśyas, the people of Kāśi or Benares. Conjevaram, nevertheless, is a place of special sanctity, and is one of the seven holy cities of India. Hwen Thsang speaks of it in the 7th century A.D. as the capital of Drāviḍa. It was then a great Buddhist centre, but about the 8th century began a Jain epoch, and that was succeeded by a period of Hindu predominance (Imp. Gaz. of India, Art. Conjevaram).

This form is not in the dictionary; but it is no doubt the same as Tailanga or Tri-liṅga, that is Teliṅga, the modem Telugu country. It coincided more or less with the ancient kingdom of Andhra (see page 337 note §). I have not found this name in any shape in the Rāmāy. or MahāBhārata; Andhra is the name which occurs in those books.

This probably means “the valleys of the Kuñjara hills,” and the reference may be to mount Kuñjara, which is mentioned in the Rāmāy. as situated in the South, but not in a clear manner (Kiṣk.-K., xli. 50). I have not met the name elsewhere, but as this place is joined with Kaccha in one compound (see next note) it may mean part of the Travancore hills. Kuñjara-darī is given in the dictionary as the name of a place.

This is Kochchi, the modem Cochin, in Travancore. It is not I believe mentioned in the Rāmāy. or MahāBhārata, except once in the latter book in the account of Sahadeva’s conquests in the South (Sabhā-P., xxx. 1176). Both Christians and Jews are said to have settled here early in the Christian era, and they were firmly established here by the 8th century.

This is the name of the modern river Chittar in the extreme South (see page 303, note ‡‡), and also of the district near it. It appears, moreover, to be the name of a hill in the extreme South (Bhīṣma-P., vi. 252). It is also the name of a town in Ceylon, after which the name was extended to the whole island (dictionary). The island seems to be meant by the words Tāmrāhvayadvīpa in the MahāBhārata (Sabha-P., xxx. 1172).

Vāhya-pādas; the right hind foot is meant as is stated expressly in verse 33, but (because perhaps this word is vague) the names that follow are sadly confused and belong to all regions in the west and north-west.

See page 314, note *; these also are out of place.

This should perhaps be connected with Baḍavā, a tīrtha apparently in Kashmir (Mahā-Bhārata, Vana-P., lxxxii. 5034-42). A river of the same name is mentioned (id., ccxxi. 14232), but that seems from its context to be rather in South India. Badavā-mukha (which means ‘submarine fire’) may also mean “having faces like mares”; and a people called Aśva-mukhas are mentioned in Matsya Purāṇa, cxx. 58, as dwelling north of the Himalayas: see also verse 43 below.

See page 315, note *; they are hardly in place here.

See page 315, note †; these are out of place here.

See page 340 note §. The name is derived from an eponymous king Ānarta, who was the son of Śaryāti one of the sons of Manu Vaivasvata (Hari-Vaṃśa, x. 613 and 642—9).

“Those who have faces like women.” I have not met this name elsewhere. It seems, however, to be a proper name and not an adjective.

This as a name is not in the dictionary, and I have not found it elsewhere.

Or “and the Argigas or Ārgigas,” as the text may be read. These names are not in the dictionary and I have not met with them elsewhere. Perhaps the correct reading should be Śāryātas. They were a tribe, so-called from their chief Śaryāta the Mānava, who settled down near where the ṛṣi Cyavana dwelt, and gave his daughter Sukanyā to the ṛṣi to appease his wrath (Śata-P. Brāh., IV. i. 5). He is called Śaryāti in the MahāBhārata (Vana-P., cxxi. 10312; and cxxii.) where the same story is told rather differently; and also in the Harivaṃśa, where he is said to be a son of Manu and progenitor of Ānarta and the kings of Ānarta (x. 613, and 642-9). Prom all these pas-sages it appears the Śāryātas were in the West, in Gujarat; and Cyavana as a Bhārgava is always placed in the West, near the mouths of the Narbada and Tapti. But perhaps the most probable reading is Bhārgavas; they were in the West (see page 310, note †).

See page 313 note ‡.

This name is not in the dictionary and I have not found it elsewhere. It can havo nothing to do with Karṇa one of the heroes of the MahāBhārata, for he reigned in Anga in the East. Prādheya means a descendant of Prādhā, one of Dakṣa’s daughters, and that also is inadmissible. It suggests Rādheya, which was a metronymic of Karṇa, but that is equally unsuitable. It seems therefore the words must be taken as a whole forming one name, and then it suggests comparison with Karṇa-prāvāra which would be the same as Karṇa-prāvaraṇa (see page 346, note †).

See page 319, note *. This word is compounded with the preceding name; it hardly seems to be in place here.

See page 322, note ‖; they seem to be out of place here, unless any Kirātas inhabited the southern part of the Aravalli hills or the extreme western part of the Vindhya mountains, and that seems improbable. See also Adhama-kairātas in verse 44 below, and Kirātas are mentioned again in verse 50.

See page 317, note *; they seem to be out of place here.

These people are out of place here; see page 331, note §; they should be properly in the right flank.

I have not met this name elsewhere; but, no doubt, it denotes some people, who claimed descent from Paraśu-Rāma and who would therefore be somewhere on the western coast between Bombay and the Narmadā; see page 310, note †. It is said there was a dynasty of Pāraśava kings after the great Paurava line came to an end (Matsya Purāṇa, 1.73-76) but it does not appear where.

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not met it elsewhere. It suggests a connexion with the Kālibalas of canto lvii, verse 49; but Kala also means, “emitting a low or inarticulate sound,” and it was an old fable that a people existed, who could not speak articulately, but hissed like serpents, see Mandeville’s Travels, chap, xviii. and xix. Kala occurs again in verse 36.

I have not found this elsewhere as the name of a people. The word however means “a rogue” and may be an adjective to Haima-girikas.

The people of Hema-giri. This is not given as the name of a place in the dictionary, but it may be a synonym for Hema-hūta or Hema-śṛṅga. It is said in the MahāBhārata the latter is the portion of Himavat from which the Ganges issued formerly (Ādi-P., clxx. 6454-5), and Hiraṇya-śṛṅga is probably the same (Bhīṣma-P., vi. 237). Hema-kūṭa was near the rivers Nandā and Apara-nandā and between the sources of the Ganges and Kauśiki (Vana-P.,. cx. 9968-87); and it is alluded to in other passages but they are not clear (e.g., id., clxxxix. 12917; Bhīṣma-P., vi. 198, 202, 236 and 246). The last of these passages says the Guhyakas dwell on Hema-kūṭa. The Matsya Purāṇa says Hema-śṛṅga is south-east of Kailāsa, and the R. Lauhitya, or Brahmaputra, rises at its foot (cxx. 10-12); and that two rivers rise in Hema-kūṭa which flow into the eastern and western seas (ibid., 61-5).

This seems to he erroneous, yet it is not easy to suggest an amendment. The first part, no doubt, refers to the R. Sindhu and the Sindhu people but the latter part appears unintelligible. Perhaps the reading should be Sindhu - kūla-suvīrakāḥ or Sindhavāś ca suvīrakāḥ meaning the Sindhus and the Suvīras (see page 315, notes * and †); but these two people have been mentioned already in verse 30.

The people of Surāṣṭra; see page 340, note ‡.

See page 318, note ‖. They are quite out of place here.

The Drāviḍas are often alluded to in the MahāBhārata (e.g., Sabhā-P, xxxiiL 1271; Vana-P., li. 1988; Karṇa-P., xīi. 454; &c.), but are not mentioned in the Rāmāy., I believe, except in the geographical canto (xli. 18). They are sometimes closely connected with the Pāṇḍyas (Sabhā-P., xxx. 1174), but the name was applied in a general way to denote the southern branches of the races now classed as Dravidian, and it is the same as Tamil (Caldwell’s Grammar of the Dravidian Languages, pp. 12-15). Their territory included the sea coast in early times (Vana-P., cxviii. 10217). It is also said they were kṣattrīyas and became degraded from the absence of brahmans and the extinction of sacred rites (Anuśās.-P., xxxiii. 2104-5; Manu, x. 43-44).

I have not met this name elsewhere. It means “dwelling by the ocean,” and is probably an epithet of Drāvidas, for they bordered on the sea as mentioned in the last note.

The plural seems peculiar.

Or Ana-rādhā.

I have not met this elsewhere. It may be the same as Mt. Maṇi-mat (Droṇa-P., lxxx. 2843); which appears to be also intended in Vana-P., lxxxiī. c043, and if so would denote the range of hills enclosing Kashmir on the south, according to the context. It may also be the same as the “jewelled mountain Su-megha” mentioned in the Rāmāy. (Kiṣk.-K., xliii. 40).

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not found it elsewhere.

This is not in dictionary as the name of a mountain, and I have not found it elsewhere.

This does not appear to be the name of any particular mountains, but rather denoted in a vague way mountains in the west behind which the sun sets. It is mentioned in the Rāmāy. as Asta-giri (Kiṣk.-K., xxxvii. 22), and as Asta-parvata (id., xliii. 54).

See note to Aparāntas, page 313, note †. This half line Aparāntika Haihayāśca is a syllable too long; it would be better to read either Aparāntā or omit the ca.

The Haihayas were a, famous race, the descendants of an eponymous king Haihaya, who is said to have been a grandson or great-grandson of Yadu, the eldest son of Yayāti (Hari-Vaṃśa, xxxiii. 1843-4; and Matsya Purāṇa, xliii. 4-8. Yadu is said to have been king of the north-east region (Hari-Vaṃśa, xxx. 1604, 1618), but the references to the earliest movements of the Haihayas are hardly consistent. Mahiṣ-mat, who was fourth in descent from Haihaya, is said to have founded the city Māhiṣ-matī on the Narmada (see page 333, note ‡; and id., xxxiii. 1846-7), and his son Bhadra-śreṇya is said to have reigned in Kāśi or Benares, which the Vītahavya branch of the Haihayas had previously conquered from its king Haryaśva, but Haryaśva’s grandson Divodāsa defeated them and regained his capital (Mahā-Bhārata, Anuśās.-P., xxx. 1949-62; Harivaṃśa, xxix. 1541-6; and xxxiī. 1736-46). The great king Arjuna Kārtavīrya, who was ninth in descent (Hari-Vaṃśa, xxxiii. 1850-90; and Matsya P., xliii. 13-45), reigned in Anūpa and on the Narmadā and had the great conflict with Rama Jāmadagnya, which ended in the overthrow of the Haihayas (Mahā-Bhārata, Vana-P., cxvi. 10189—cxvii. 10204; and Śānti-P., xlix. 1750-70; and pages 338 note *, and 344 note *). The Haihayas and Tālajanghas in alliance with Śakas, Yavanas, Kāmbojas and Pahlavas are said to have driven Bāhu king of Ayodhyā out of his realm, but his son Sagara drove them out and recovered the kingdom (Vana-P., cvi. 8831-2; and Hari-V, xiii 760 — xiv. 783).

The Haihaya race comprised the following tribes, Vītihotras (or Vita-havyas P), Śāryātas, Bhojas, Avantis, Tauṇḍikeras (or Kuṇḍikeras), and Tālajanghas j the Bharatas, Sujātyas and Yādavas are added, and the Śiīrasenas, Anartas and Cedis also appear to have sprang from them (Hari-Vaṃśa, xxxiv. 1892-6; and Matsya-P., xliii. 46-49). Comparing the territories occupied by these tribes, it appears the Haihaya race dominated nearly all the region south of the Jumna and Aravalli hills as far as the valley of the Tapti inclusive of Gujarat in ancient times (see pages 333 note ‡, 335 note §, 340 note §, 342 note ‡, 344 all the notes, 351 note 352 note *, and 368 note §§); and Cunningham says that two great Haihaya States in later times had their capitals at Manipur in Mahā Kosula (or Chhattisgarh) and at Tripura (or Tewar) on the Narbada (Arch. Sarv. Repts., IX. 51-57).

I have not met this elsewhere, and it is not in the dictionary as the name of a people. It may be the same as the Śāśikas (Mahā-Bhārata, Bhīṣma-P., ix. 354; perhaps the Śaśakas in Vana-P., ccliii. 15257 are the same); or the reading may be Śākalas, the people of Śākala, the capital of Madra (see page 315, note, ‡).

This is not in the dictionary and I have not met it elsewhere. It appears to be a proper name and not an adjective.

This is not in the dictionary and I have not found it elsewhere. Perhaps the reading should be Kokanadas, a people in the north-west classed with the Trigartas and Dārvas (M.-Bh, Sabhā-P., xxvi. 1026), or Kokarakas who seem to be the same (Bhīṣma-P., ix. 369).

This is given in the dictionary as the name of a people, but I have not met it elsewhere. Perhaps a better reading would be Pañcodakas or Pañcanadas, “the people living beside the R. Pañcanada,” which appears to be the single stream formed by the confluence of the five rivers of the Pañjab (Mahā-Bhārata, Vana-P., Ixxxii. 5025; Bhīṣma-P., lvi. 2406; and dictionary); but this name seems to be also applied to the five rivers collectively (Vana-P., ccxxi. 14229), and to the country watered by those five rivers (Sabhā-P., xxxi. 1193; Udyoga-P., iii 82; and xviii. 596-601; Karṇa-P., xlv. 2100 and 2110; &c.; Harivaṃśa, xcii. 5018; and Rāmāy., Kiṣk.-K., xliii. 21), and to the inhabitants of it (Bhīṣma-P., lvi. 2406; and Karṇa-P., xlv. 2086): see also Lassen’s map (Ind. Alt).

This is given in the dictionary as the name of a people, but I have not found it elsewhere. Perhaps a better reading would be Vānavas, who are mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Vana-P., ix. 362), or Vamāyavas. There was a district called Vanāyu or Vāndyu, which appears to have been situated in the north-west, and which was famous for its breed of horses (Mahā-Bhārata, Bhīṣma-P., xci. 3974; Droṇa-P., cxxi 4831; Karṇa-P, vii 200; and Rāmāy., Ādi-K., vi 24). It appears to be the modern Bunnu in the north-west of the Pañjab.

This is not given as the name of a people, and the word means, “low,” and “western.” This name may be compared with Aparas, a people mentioned in the Rāmāy. (Kiṣk.-K., xliii 23); and see page 313, note † and Aparāntikas in verse 34. But a. better reading for the text hy-avarās is perhaps Varvarās; see page 319, note * and page 369, note *.

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not met with it elsewhere; but Tārakṣati and Tārakṣiti are given as the name of a district to the west of Madhya-deśa. There was also a kingdom called Turuṣka ṃ Inter times (Arch. Surv. of W. India, Memo. No. 10, p. 7). The Turuṣkas are the Turks, and their country Turkestan. A people called Tārkṣyas are mentioned in MahāBhārata, Sabhā-P., li. 1871.

I have not found this elsewhere, and it is not in the dictionary. A place called Anga-loka is assigned to the west in the Rāmāy. (Kiṣk.-K., xliii. 8), and Aṅgas and Anga-lokyas are mentioned to the north of India in the Matsya Purāṇa (cxx. 44 and 45).

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not found it elsewhere. A river Śārkarāvartā is mentioned (Bhāgavata Purāṇa-V., xix. 17), but appears to be in the south. A great house-holder and theologian Jana Śārkarākṣya is alluded to (Chāndogya-Up.-V., xi. 1). Perhaps the reading may be Śākalas, the people of Śākala the capital of Madra (see page 315, note ‡).

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not found it elsewhere. It suggests śāla-veśmakas, “those who live in houses with spacious rooms,” and it may be an adjective to Śarkaras. Perhaps we should read Śālvas as the first part of the word (see page 349, note §) but, if so, the latter part seems unrecognizable.

I have not met with this elsewhere, and it is not in the dictionary. It may be an adjective, “deep-voiced,” describing the Phalguṇakas, Perhaps the reading should be Gurjaras They appear to have been settled ip the Pañjab or Upper Sindh, and to have been driven out by the Bālas about 500 A.D., and pushed gradually southward, till at length they occupied the country around the peninsula of Kathiawar, thence called Gujarat after them Cunningham, Arch. Surv. Repts., II 64-72). Or perhaps the reading might be Gurusthala; a river Guru-nadī is mentioned in the west region, but without data to identify it (Hari-Vaṃśa, clxviii. 9516-8).

Or better, Phalgunakas. I have not met with it elsewhere, A similar name Phalgulukas occurs just below.

This is not in the dictionary, and I have not met with it elsewhere. It occurs again in verse 39. A people called Veṇikas are mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Bhīṣma-P., li. 2097).

This resembles Phalguṇakas above. I have not found it elsewhere. A mountain called Phena-giri or Phala-giri is mentioned in the Rāmāy. as situated in the west near the mouth of the Indus (Kiṣk.-K., xliii. 13-17, and Annotations).

These are no doubt the same as the Ghorakas mentioned in the MahāBhārata, Sabhā-P., li. 1870; but I have not found any data to fix their position.

I have not met this elsewhere, but it is stated in the dictionary to be the name of a people in Madhya-deśa, and the word is also written Guḍuha, Gulaha and Guluha.

This has occurred before in verse 31.

“The one-eyed.” It was an old belief that such people existed. “Men with only one eye in their forehead” are mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Sabhā-P., 1. 1837); the Cyclopes are famous in Greek and Latin literature; and a one-eyed race is spoken of as dwelling somewhere in the Indian Ocean by Mandeville (Travels, Chap XIX).

“Those who have hair or manes, like horses.” I have met no such name elsewhere, except that the synonymous name Aśva-keśas occurs in the next line of this verse. Neither is it in the dictionary.

“The long-necks.” I have met no such name elsewhere.

This name is the same as the Culikas mentioned in canto lvii. verse 40, but the position does not quite agree; these are in the west and the others in the north. A people Vindha-culalcas are named in the Bhishma-P. list (ix. 369) and appear to be in the north A dynasty of kings called Cūlikas is said to have reigned after the great Paurava line came to an end (Matsya Purāṇa, 1. 73-76).

“Those who have hair, or manes, like horses.” It is the same as Vāji-keśas mentioned above.

For Aindra-mūlam read Aindram mūlnm. Aindra is the same as Jyeṣṭhā.

They are mentioned again in verse 46. They may be a tribe which claimed descent from the ṛṣi Māṇḍavya, to whom Janaka king of Videha is said to have sung a song (Mahā-Bhārata, Śānti-P., cclxxvii), and whose hermitage is alluded to, as situated somewhere perhaps between Oudh and North Behar (Udyoga-P., clxxxvii. 7355); but Māṇḍavya-pura is said in the dictionary to be situated on the R. Godavari. A people called Maṇḍikas are mentioned in the MahāBhārata (Vana-P., ccliii. 15243). The Vimāṇḍavyas are named in verse 6 above.

I have not met this name elsewhere, nor is it in the dictionary; but it suggests Kandahar, and the position agrees. A people Carma-khaṇḍikas are mentioned in canto lvii. verse 36.