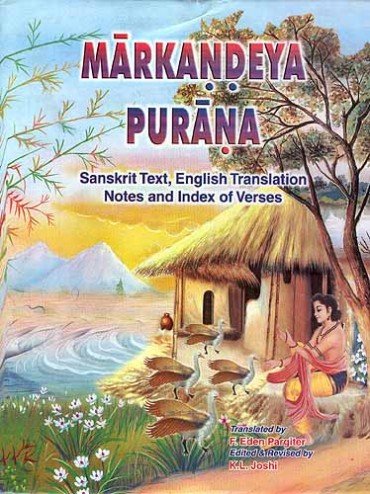

The Markandeya Purana

by Frederick Eden Pargiter | 1904 | 247,181 words | ISBN-10: 8171102237

This page relates “kuvalayasva’s visit to patala” which forms the 23rd chapter of the English translation of the Markandeya-purana: an ancient Sanskrit text dealing with Indian history, philosophy and traditions. It consists of 137 parts narrated by sage (rishi) Markandeya: a well-known character in the ancient Puranas. Chapter 23 is included the section known as “conversation between Sumati (Jada) and his father”.

Canto XXIII - Kuvalayāśva’s visit to Pātāla

Kuvalayāśva, returning home, learnt what had happened—He mourns his loss, and shunning women lives a cheerful life—The Nāga king Aśvatara, hearing this story, engages in austerities and extols Sarasvatī—Sarasvatī, propitiated by him, restores him his companion Kambala, and gives them both perfect skill in poetry and music—Both propitiate Śiva, who at their request gives Aśvatara Madālasā as his daughter, restored to life as before—At Aśvatara’s suggestion, his sons invite Kuvalayāśva to their palace in Bātāla and introduce him to their father—Aśvatara asks Kuvalayāśva to relate his story.

The sons spoke:

The king’s son reaching then his own city in haste, desirous to salute his parents’ feet respectfully, and eager to see Madālasā, beheld some people of the city downcast, with joyless countenances, and then again astonished with joyful faces: and other people with wide-open eyes, exclaiming “Hurrah! hurrah!” embracing one another, filled with the utmost curious interest. “Long mayest thou live, O most fortunate prince! Thy adversaries are slain; gladden thy parents’ mind and ours also, which is relieved of anxiety.

Surrounded before and behind by the citizens who were crying out thus, his joy forthwith aroused, he entered his father’s palace. And his father and mother and other relations embraced him, and then invoked on him auspicious blessings, saying “Long mayest thou live!” Thereupon having done obeisance, surprised at what this might mean, he questioned his father; and he duly explained it to him.

On hearing that his wife Madālasā, the darling of his heart, was dead, and seeing his parents before him, he fell into the midst of a sea of shame and grief. He thought, “The maiden, on hearing I was dead, gave up life, the virtuous one: fie on me harsh-minded that I am! Malignant am I, worthless am I, that I live most pitiless, when deprived of that deer-eyed one who encountered death for my sake!” Again he thought, having firmly composed his mind, banishing hastily the rising distraction, and breathing hard outwards and inwards, feeling undone.

“If I abandon life because she has died on my account, what benefit shall I confer on her? Yet this would be praiseworthy in women’s opinion. Or if being downcast I weep, repeatedly exclaiming ‘ah! my beloved,’ still this would not be praiseworthy in us; for we are men assuredly. Frigid with grief, downcast, uṅgarlanded, uncleansed, I shall then become an object of contumely to my adversaries. I must cut off my enemies, and obey the king, my father. And how then can I resign my life which is dependant on him? But here, I consider, I must renounce pleasure with woman, and yet that renunciation does not tend to benefit the slender-limbed one. Nevertheless in every way I must practise harmlessness, which works neither benefit nor injury. This is little for me to do on her account who resigned her life on mine.”

The sons spoke:

Having thus resolved, Ṛtadhvaja then performed the ceremony of offering water, and immediately afterwards performed the obsequies; and he spoke again.

Ṛtadhvaja spoke:

“If she, Madālasā, the slender-limbed, were not my wife, I would not have another companion in this life. Besides that fawn-eyed daughter of the Gandharva, I will not love any woman—so have I spoken in truth. Having given up that wife, who observed true religion, whose gait was like the elephant’s, I will not assent to any wo man —this have I declared in truth.”

The sons spoke:

And having renounced, dear father, all the delights of Woman, bereft of her, he continued to sport in company with his peers, his equals in age, in the perfection of his good disposition. This was his supreme deed, dear father. Who is able to do that which is exceedingly difficult of accomplishment by the gods, how much more so by others?

Jaḍa spoke:

Having heard their speech, their father became dissatified; and after reflecting the Nāga king addressed his two sons, as if in ridicule.

The Nāga king Aśvatara spoke:

“If men, deeming a thing impossible, will put forth no effort in the deed, from the loss of exertion there ensues loss. Let a man undertake a deed, without squandering his own manhood; the accomplishment of a deed depends on fate and on manhood. Therefore I will so strive, my sons, henceforth—let me so practise austerities diligently,—that this may in time be accomplished.”

Jaḍa spoke:

Having spoken thus, the Nāga king went to Plakṣāvataraṇa,[1] the place of pilgrimage on the Himavat mountain, and practised most arduous austerities. And then he praised the goddess Sarasvatī there with his invocations, fixing his mind on her, restricting his food, performing the three prescribed ablutions.[2]

Aśvatara spoke:

“Desirous of propitiating the resplendent goddess Jagad-dhātrī Sarasvatī, who is sprung from Brahmā, I will praise her, bowing my head before her. Good and bad, O goddess, whatever there he, the cause that confers alike final enancipation and riches,—all that, conjoint and separate, resides in thee, O goddess. Thou, O goddess, art the imperishable and the supreme, wherein everything is comprised; thou art the imperishable and the supreme, which are established like the Atom. The imperishable and the supreme is Brahma, and this universe is perishable by nature. Fire resides in wood, and the atoms are of earth. So in thee resides Brahma, and this world in its entirety; in thee is the abode of the sound Om, and whatever is immoveable and moveable, O goddess. In thee reside the three prosodial times,[3] O goddess, all that exists and does not exist, the three worlds,[4] the three Vedas, the three sciences,[5] the three fires,[6] the three lights,[7] and the three colours,[8] and the law-book; the three qualities, the three sounds,[9] the three Vedas, and the three āśramas,[10] the three times, and the three states of life, the pitṛs, day, night and the rest. This trinity of standards is thy form, O goddess Sarasvatī! The seven soma-saṃsthā sacrifices, and the seven haviḥ-saṃsthā sacrifices, and the seven pāka-saṃsthā[11] sacrifices, which are deemed the earliest by those who think differently, and which are as eternal as Brahma,[12] are performed by those, who assert that all things are Brahma, with the utterance of thy name, O goddess. Undefinable, composed of half a measure, supreme, unchanging, imperishable, celestial, devoid of alteration is this thy other supreme form which I cannot express. And even the mouth does not declare it, nor the tongue, the copper-coloured lip, or other organs. Even Indra, the Vasus, Brahmā, the Moon and Sun, and Light cannot declare thy form, whose dwelling is the universe, which has the form of the universe; which is the ruler of the universe, the Supreme Ruler; which is mentioned in the discussions of the Sāṅkhya and Vedānta philosophies, and firmly established in many Śākhās; which is without beginning middle or end; which is good, bad, and neutral; which is but one, is many, and yet is not one; which assumes various kinds of existence; which is without name, and yet is named after the six guṇas, is named after the classes, and resides in the three guṇas; which is one among many powerful, possesses the majesty of the Śaktis, and is supreme. Happiness and unhappiness, having the form of great happiness, appear in thee. Thus, O goddess, that which has parts is pervaded by thee, and so also that which has no parts; that which resides in non-duality, and that which resides in duality (O brahman). Things that are permanent, and others that perish; those again that are gross, or those that are subtler than the subtle; those again that are on the earth, or those that are in the atmosphere or elsewhere;—they all derive their perceptibility from thee indeed. Everything—both that which is destitute of visible shape, and that which has visible shape; or whatever is severally single in the elements; that which is in heaven, on the surface of the earth, in the sky or elsewhere;—is connected with thee by thy vowels and by thy consonants!”

Jaḍa spoke:

Thereupon, being praised thus, the goddess Sarasvatī, who is Viṣṇu’s tongue, answered the high-souled Nāga Aśvatara.

Sarasvatī spoke:

“I grant thee a boon, O Nāga king, brother of Kambala speak therefore: I will give thee what is revolving in thy mind.”

Aśvatara spoke:

“Give thou me, O goddess, Kambala indeed my former companion, and bestow on us both a conversance with all sounds.”

Sarasvatī spoke:

“The seven musical notes,[13] the seven modes in the musical scale,[14] O most noble Naga! the seven songs also,[15] and the same number of modulations,[16] so also the forty-nine musical times,[17] and the three octaves[18]—all these thou and also Kambala shalt sing, O sinless one! Thou shalt know more yet through my favour, O Naga king. I have given thee the four kinds of quarter-verse,[19] the three sorts of musical tunes,[20] the three kinds of musical movement,[21] also the three pauses in music,[22] and the four-fold todya.[23] This thou shalt know through my favour O Nāga king, and what lies further. What is contained within this and dependant thereon, measured in vowels and consonants—all that I have given to thee and Kambala. I have not so given it to any other on the earth or in Pātāla, O Nāga: and ye shall be the teachers of all this in Pātāla and in heaven and on earth also, ye two Nāgas!”

Jaḍa spoke:

Having spoken thus, the lotus-eyed goddess Sarasvatī, the tongue of all, then disappeared at once from the Nāga’s view. And then, as it all happened to those two Nāgas, there was begotten in both the fullest knowledge in versification, musical time, musical notes, &c.

Then the two Nāgas, observing musical time on the lutestrings, being desirous of propitiating with seven songs the lord who dwells on the peaks of Kailāsa and Himālaya, the god Śiva, who destroyed Kama’s body, both exerted themselves to the utmost, with voice and tone combined, being assiduous morning, night, noon and the two twilights. The bull-bannered god, being long praised by them both, was gratified with their song, and said to both, “Choose ye a boon.” Thereon Aśvatara with his brother doing reverence made request to Śiva, the blue-throated, Umā’s lord,—

“If thou, O adorable three-eyed god of the gods, art pleased with us, then grant us this boon according to our desire: let Kuvalayāśva’s deceased wife, Madālasā, O god, at once become my daughter of the same age as when she died, remembering her life as before, endowed with the selfsame beauty, as a devotee, and the mother of Toga; let her be born in my house, O Śiva.”

Śiva spoke:

“As thou hast spoken, most noble Nāga, it shall all happen through my favour, in very truth. Hearken also to this, O Nāga. But when the śrāddha is reached, thou shouldst eat the middle piṇḍa by thyself, most noble Nāga, being pure, and having thy mind subdued; and then, when that is eaten, the happy lady shall rise out of thy middle hood, the same in form as when she died. And having pondered on this thy desire, do thou perform the libation to the piṭris; immediately she, the fine-browed, the auspicious, shall rise out of thy breathing middle hood, the same in form as when she died.”

Having heard this, both then adored Śiva, and returned, full of contentment, to Rasātala. And so the Nāga, Kambala’s younger brother, performed the śrāddha, and also duly ate the middle piṇḍa; and, while he pondered on that his desire, the slender-waisted lady was produced[24] at once, in the selfsame form, out of his breathing middle hood. And the Nāga told that to no one: he kept her, the lovely-teethed one, concealed by his women in the inner apartments.

And the two sons of the Nāga king pursuing pleasure day by day, played[25] with Ṛtadhvaja like the immortals. But one day the Nāga king, being intoxicated, spoke to his sons, “Why indeed do ye not do as I told you before? The king’s son is your benefactor in my opinion; why do ye not confer a benefit on him, the pride-inspirer? Thereupon they both, being thus admonished by their kindly-affectioned father, went to their friend’s city, and enjoyed themselves with the wise prince. Then both, after having held some other talk with Kuvalayāśva, invited him respectfully to come to their house. The king’s son said to them, “Is not this your house? Whatever is mine, riches, carriages, garments, &c., that is indeed yours. But whatever ye desire should he given you, riches or jewels, let that be given you, O young dvijas, if ye have friendly regard for me. Am I cheated by such a cruel fate as this, that ye do not evince any sense of ownership in my house F If ye must do me kindness, if I am to receive favour from you, then consider my wealth and home as your own. Whatever is yours is mine, mine is your own. Believe ye this in truth. My life has gone out into you. Never again must ye speak of separate property, O virtuous dvijas: since ye are devoted to my favour, I have adjured you by my heart affectionately.”

Thereupon both the young Nāgas, their faces beaming with affection, replied to the king’s son, somewhat feigning anger. “Ṛtadhvaja, without doubt, we must not think in our mind in this matter otherwise than thou hast now spoken. But our high-souled father has himself repeatedly said this—‘I wish to see that Kuvalayāśva.’” Thereon Kuvalayāśva rising from his seat of honour, prostrated himself on the ground, saying, “Be it as your dear father says.”

Kuvalayāśva spoke:

“Happy am I! Most rich in merit am I! Who else is there like me, that your father shews an earnest mind to see me? Rise ye therefore, let us go: not even for a moment do I wish to transgress his command here. I swear by his feet!”

Jaḍa spoke:

Having spoken thus the king’s son went with them both, and issuing from the city reached the holy river Gomatī. They passed through it, the Nāga princes and the king’s son: and the king’s son thought their home lay on the other side of the river. And drawing him, thence, they led the prince to Pātāla; and in Pātāla he beheld them both as young Nāgas, lustrous[26] with the gems in their hoods, displaying the svastika marks. Gazing with eyes wide open with amazement at them both, who were most handsomely formed, and smiling he spoke kindly—“Bravo! most noble dvijas!”

And they told him of their father, the Nāga king, Aśvatara by name, peaceful, worthy of honour by the heaven-dwellers.

Then the king’s son saw charming Pātāla; which was adorned with Nāgas, young adult and old, and also with Nāga maidens, who were playing here and there, and who wore beautiful ear-rings and necklaces, as the sky is decked with stars; and elsewhere resounding with drums, small drums, and musical instruments, mingled with the strains of singing, which kept time with the sounds of lutes and pipes; filled with hundreds of charming houses. Gazing about on Pātāla Śatrujit’s son the foe-queller, walked about accompanied by those two Nāgas his friends.

Then they all entered the Nāga king’s residence, and they saw the high-souled Nāga king seated, clad in heavenly garlands and raiment, adorned with gems and ear-rings, resplendent with superb pearl-necklaces, decorated with armlets, blessed with good fortune, on a throne all of gold, the frame of which was overlaid with a multitude of gems coral and lapis lazuli.

They showed the king to him saying “That is our father and they introduced him to their father, saying “This is the hero Kuvalayāāva.” Then Ṛtadhvaja bowed at the feet of the Nāga king. Raising him up by force, the Naga king embraced him warmly, and kissing him on the head he said “Long mayest thou live, and destroying all thy foes, be submissive to thy father. My son thy virtues have been mentioned even in thy absence, happy that thou art; thy rare virtues have been reported to me by my two sons. Mayest thou indeed prosper thereby in mind, speech, body and behaviour: the life of a virtuous man is praise-worthy; a worthless man although alive is dead. A virtuous man, while accomplishing his own good, brings complete satisfaction to his parents, anguish into the hearts of his enemies, and confidence among the populace. The gods, the pitṛs, brāhmans, friends, suppliants, the maimed and others, and his relatives also desire a long life for the virtuous man. The life of virtuous men, who eschew abuse, who are compassionate towards those in trouble, who are the refuge of those in calamity, abounds in good fruit.”

Jaḍa spoke:

Having spoken thus to that hero, the Nāga next addressed his two sons thus, being desirous to do honour to Kuvalayāśva. “When we have finished our ablutions and all the other proceedings in due order, when we have drunk wine and enjoyed other pleasures, when we have feasted up to our desire, we shall then with joyful minds spend a short time with Kuvalayāśva in hearing the story of the success of his heart’s festival.” And atrujit’s son assented in silence to that speech. Accordingly the lofty-minded king of the Nāgas did as he had proposed.

The great king of the Nāgas, true to his word, assembling with his own sons and the king’s son, filled with joy, feasted on foods and wines, up to fitting bounds, self-possessed and enjoying pleasure.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Where the R. Sarasvatī takes its rise.

[2]:

At morning, noon, and evening.

[3]:

Mātrā; short, long, and prolated.

[4]:

Loka; earth, atmosphere and the sky.

[5]:

Vidyā; metaphysics (with logic), the art of government, and the practical arts (?)

[6]:

Pāvaka; gārhapatya, āhavanīya, and dakṣiṇa.

[7]:

Jyotis; fire on the earth, ether in the atmosphere, and the sun in the Sky.

[8]:

Varna; or, the three castes.

[9]:

Sabda.

[10]:

Āśrama; those of the gṛha-stha, vana-prastha, and bhikṣn.

[11]:

The names of these sacrifices are thus given me by the Pandit of the Bengal Asiatic Society. The Soma-saṃsthā are

- agni-ṣṭoma,

- atyaṅgi-ṣṭoma,

- ukthya,

- ṣodaśin,

- atirātra,

- vājaheya, and

- āptor-yāma.

The haviḥ-saṃsthā are

- agnyādheya,

- agni-hotra,

- darśa-pūrnamāsan,

- cāturmāsyani,

- paśu-bandha,

- sautra-maṇi, and

- nbsp;agrajaṇeṣṭi.

The pāka-saṃsthā are given differently by different authors. According to Āpastamba they are

- aupāsana-homa,

- vaiśva-deva,

- pārvṇa,

- aṣṭakā,

- śrāddha,

- sarpa-bali,

- isāna-bali.

According to Baudhāyaṇa,

- huta,

- prahuta,

- āhuta,

- śūlagava,

- bali-haraṇa,

- pratyavarohaṇa, and

- aṣṭakā-homa.

According to Gautama,

- aṣṭakā,

- parvaṇa,

- śrāddha,

- śravaṇi,

- āgrahāyam,

- caitrī, and

- āśvayuji.

[12]:

A MS. in the Sanskrit College reads ādye for ādyā, and sanātane for sanātanāḥ; with this reading the first line of the verse would qualify devi sarasvati, if sanātane be taken as an ārṣa form of sanātani. But these verses seem obscure.

[13]:

Svara, a “musical note.” There are 7 svaras, viz., ṣaḍja, ṛṣabha, gāndhāra, madhyama, pañcama, dhaivata, and niṣāda; and they are designated by their initial sounds, sa, ri, ga, ma, pa, dha, and ni: but the arrangement varies, and Prof. Monier-Williams in his dictionary places niṣāda first, ṣaḍja fourth, and pañcama seventh. Those 7 svaras compose the “musical scale,” grāma (Beng. saptak). The interval between each consecutive pair of notes is divided into several ‘lesser notes’ called śruti; thus there are 4 between sa and ri, 3 between ri and ga, 2 between ga and ma, 4 between ma and pa, 4 between pa and dha, 3 between dha and ni, and 2 betweeen ni and sa in the higher octave—that is 22 śrutis in all. The svaras correspond to the ‘natural notes,’ and the śrutis to the ‘sharps and flats’ in European music. (Raja Sourindro Mohun Tagore’s Saṅgīta-sāra-sangraha, pp. 22—24, where the names of the śrutis are given; and his Victoria-gīti-mālā in Bengali, Introduction.)

[14]:

Grāma-rāga. I do not find this in the dictionary. Does it mean the “series of musical scales” that can be formed by taking each of the notes (svara) as the ‘key’ note? Thus there would be 7 scales, as there are 7 notes. But Raja S. M. Tagore calls this svara-grām (Beng.), and he says that only 3 such scales were common in early times, via., those with ṣaḍja, gāndhāra and madhyama as key notes (Victoria-gīti-mālā, Introduction, p. 2).

[15]:

Gītaka. I do not know what the seven songs are.

[16]:

Mūrchanā. This seems to be “running up or down the scaleit is defined thus—

Kramāt svarāṇāṃ saptānām ārohaś cāvarohaṇam

Mūrchanetyucyate grāma-traye tāḥ sapta sapta ca.

As there are 7 scales obtained by taking any of the 7 notes as the key note, there would be 7 mūrchanās; and this applies to the 3 octaves (grāmatray a), so that there are 21 mūrchanās altogether (Saṅgīta-sāra-sangraha, p. 30, where their names are given). But in his Bengali Treatise Baja S. M. Tagore explains mūrchanā to be the “passing uninterruptedly from one note (svara) to another, and in the process sounding all the intermediate notes and lesser notes (śruti)c This corresponds to ‘slurring.’ With this meaning the number of possible mūrchanās is almost indefinite.

[17]:

Tāla, the “division of time in music.” It consists of three things, kāla, the duration of time, kriyā, the clapping of the hands (accentuation), and māna, the interval between the clappings. It seems to correspond to the ‘bar’ and the ‘kinds of time’ in European music. European music has only 3 kinds of time, Common, Triple and Compound, each with a few subdivisions; but in Hindu music there is the utmost variety. I do not know what the 49 tālas here meant are; but Raja S. M. Tagore gives two lists of des’ī-tālas, one enumerating 120, and the other 72.

[18]:

Grāma, the “octave.” Hindu music uses only three octaves, which are called nimna (Beng. udārā), madhya (mudārā) and ucca (tārā).

[19]:

Pada.

[20]:

Tāla. This seems to refer to the classification of the tālas, viz,, śuddha, sālaṅga (or sālaṅka or sālaga, v. r.) and saṅkīrṇa, (Raja S. M. Tagore’s Saṅgīta-sāra-sangraha, p. 201); but this classification is also applied to the rāgas (see his Victoria-gīti-mālā, Introduction, p. 9.). The śuddha are explained to be the famous kinds complete in themselves; the sālanga are those produced by a mixture of two simple ones; and the saṅkīrṇa those produced by a mixture of many simple ones.

[21]:

Laya, “musical speed.” The 3 kinds are druta, quick, madhya, mean, and vilaṃbita, slow; the druta being twice as fast as the madhya, and the madhya twice as fast as the vilambita. Laya does not take account of prosodial time. This corresponds to “the movement” in European music.

[22]:

Yati, “a break in the laya” (laya-pravṛtti-niyama), ‘a rest’ in music. The 3 kinds are samā, sroto-gatā, and go-pucchā. The samā may occur at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of the laya, and in each of the 3 kinds of laya. The sroto-gatā occurs apparently when the time quickens (accelerando) after the rest, that is when the laya changes from vilambita to madhya, or from madhya to druta, or from vilambita or madhya to druta. The go-pucchā occurs apparently when the time becomes slower (rallentando, ritardando) after the rest, that is when the laya changes from druta to madhya, or from madhya to vilambita.

[23]:

Todya. I do not find this word in the dictionary. Does it mean “drum-music?”

[24]:

For yajñe read jajñe.

[25]:

Read cikriḍāte for ciktīdāte.

[26]:

Read kṛtoddyotau for kṛtodyotau.