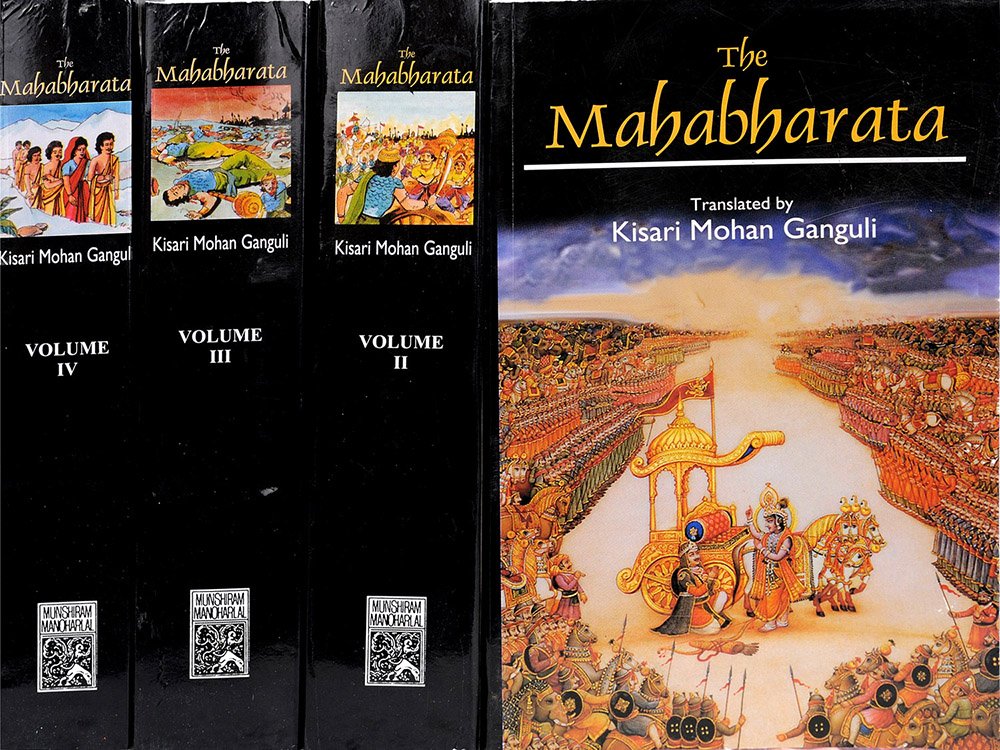

Mahabharata (English)

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section LXXXII

"Bhishma said, 'This that I have told you constitutes the first means. Listen now, O Bharata to the second means. That man who seeks to advance the interests of the king should always be protected by the king. If a person, O Yudhishthira, that is paid or unpaid, comes to you for telling you of the damage done to your treasury when its resources are being embezzled by a minister, you should grant him an audience in private and protect him also from the (impeached) minister. The ministers guilty of peculation seek, O Bharata, to slay such informants. They who plunder the royal treasury combine together for opposing the person who seeks to protect it, and if the latter be left unprotected, he is sure to be ruined. In this connection also an old story is cited of what the sage Kalakavrikshiya had said unto the king of Kosala. It has been heard by us that once on a time the sage Kalakavrikshiya came to Kshemadarsin who had ascended the throne of the kingdom of Kosala. Desirous of examining the conduct of all the officers of Kshemadarsin, the sage, with a crow kept within a cage in his hand, repeatedly travelled through every part of that king’s dominions. And he spoke unto all the men and said, ’study, you the corvine science. The crows tell me the present, the past, and the future.' Proclaiming this in the kingdom, the sage, accompanied by a large number of men, began to observe the misdeeds of all the officers of the king. Having ascertained all the affairs in respect of that kingdom, and having learnt that all the officers appointed by the king were guilty of malversation, the sage, with his crow, came to see the king. Of rigid vows, he said unto the king, 'I know everything (about your kingdom).' Arrived at the presence of the king, he said unto his minister adorned with the insignia of his office that he had been informed by his crow that the minister had done such a misdeed in such a place, and that such and such persons know that he had plundered the royal treasury. 'My crow tells me this. Admit or prove the falsehood of the accusation quickly.' The sage then proclaimed the names of other officers who had similarly been guilty of embezzlement, adding, 'My crow never says anything that is false.' Thus accused and injured by the sage, all the officers of the king, O you of Kuru’s race, (united together and) pierced his crow, while the sage slept, at night. Beholding his crow pierced with a shaft within the cage, the regenerate Rishi, repairing to Kshemadarsin in the morning said unto him, 'O king, I seek your protection. You are all-powerful and you are the master of the lives and wealth of all. If I receive your command I can then say what is for your good. Grieved on account of you whom I regard as a friend have come to you, impelled by my devotion and ready to serve you with my whole heart. You are being robbed of your wealth, I have come to you for disclosing it without showing any consideration for the robbers. Like a driver that urges a good steed, I have come hither for awakening you whom I regard as a friend. A friend who is alive to his own interests and desirous of his own prosperity and aggrandisement, should forgive a friend that intrudes himself forcibly, impelled by devotion and wrath, for doing what is beneficial.' The king replied unto him, saying, 'Why should I not bear anything you will say, since I am not blind to what is for my good? I grant you permission, O regenerate one! Tell me what you pleasest, I shall certainly obey the instructions you will give me, O Brahman,'

"The sage said, 'Ascertaining the merits and faults of your servants, as also the: dangers you incurrest at their hands, I have come to you, impelled by my devotion, for representing everything to you. The teachers (of mankind) have of old declared what the curses are, O king, of those that serve others. The lot of those that serve the king is very painful and wretched. He who has any connection with kings is to have connection with snakes of virulent poison. Kings have many friends as also many enemies. They that serve kings have to fear all of them. Every moment, again, they have fear from the king himself, O monarch. A person serving the king cannot (with impunity) be guilty of heedlessness in doing the king’s work. Indeed, a servant who desires to win prosperity should never display heedlessness in the discharge of his duties. His heedlessness may move the king to wrath, and such wrath may bring down destruction (on the servant). Carefully learning how to behave himself, one should sit in the presence of the king as he should in the presence of a blazing fire. Prepared to lay down life itself at every moment, one should serve the king attentively, for the king is all-powerful and master of the lives and the wealth of all, and therefore, like unto a snake of virulent poison. He should always fear to indulge in evil speeches before the king, or to sit cheerlessly or in irreverent postures, or to wait in attitudes of disrespect or to walk disdainfully or display insolent gestures and disrespectful motions of the limbs. If the king becomes gratified, he can shower prosperity like god. If he becomes enraged, he can consume to the very roots like a blazing fire. This, O king, was said by Yama. Its truth is seen in the affairs of the world. I shall now (acting according to these precepts) do that which would enhance your prosperity. Friends like ourselves can give unto friends like you the aid of their intelligence in seasons of peril. This crow of mine, O king, has been slain for doing your business. I cannot, however, blame you for this. You are not loved by those (that have slain this bird). Ascertain who are your friends and who your foes. Do everything thyself without surrendering your intelligence to others. They who are on your establishment are all peculators. They do not desire the good of your subjects. I have incurred their hostility. Conspiring with those servants that have constant access to you they covet the kingdom after you by compassing your destruction. Their plans, however, do not succeed in consequence of unforeseen circumstances. Through fear of those men, O king, I shall leave this kingdom for some other asylum. I have no worldly desire, yet those persons of deceitful intentions have shot this shaft at my crow, and have, O lord, despatched the bird to Yama’s abode. I have seen this, O king, with eyes whose vision has been improved by penances. With the assistance of this single crow I have crossed this kingdom of thine that is like a river abounding with alligators and sharks and crocodiles and whales. Indeed, with the assistance of that bird, I have passed through your dominions like unto a Himalayan valley, impenetrable and inaccessible in consequence of trunks of (fallen) trees and scattered rocks and thorny shrubs and lions and tigers and other beasts of prey. The learned say that a region inaccessible in consequence of gloom can be passed through with the aid of a light, and a river that is unfordable can be crossed by means of a boat. No means, however, exist for penetrating or passing through the labyrinth of kingly affairs. Your kingdom is like an inaccessible forest enveloped with gloom. You (that art the lord of it) canst not trust it. How then can I? Good and evil are regarded here in the same light. Residence here cannot, therefore, be safe. Here a person of righteous deeds meets with death, while one of unrighteous deeds incurs no danger. According to the requirements of justice, a person of unrighteous deeds should be slain but never one who is righteous in his acts. It is not proper, therefore, for one to stay in this kingdom long. A man of sense should leave this country soon. There is a river, O king, of the name of Sita. Boats sink in it. This your kingdom is like that river. An all-destructive net seems to have been cast around it. You are like the fall that awaits collectors of honey, or like attractive food containing poison. Your nature now resembles that of dishonest men and not that of the good. You are like a pit, O king, abounding with snakes of virulent poison. You resemblest, O king, a river full of sweet water but exceedingly difficult of access, With steep banks overgrown with Kariras and thorny canes. You are like a swan in the midst of dogs, vultures and jackals. Grassy parasites, deriving their sustenance from a mighty tree, swell into luxuriant growth, and at last covering the tree itself overshadow it completely. A forest conflagration sets in, and catching those grassy plants first, consumes the lordly tree with them. Your ministers, O king, resemble those grassy parasites of which I speak. Do you check and correct them. They have been nourished by you. But conspiring against you, they are destroying your prosperity. Concealing (from you) the faults of your servants, I am living in your abode in constant dread of danger, even like a person living in a room with a snake within it or like the lover of a hero’s wife. My object is to ascertain the behaviour of the king who is my fellow-lodger. I wish to know whether the king has his passions under control, whether his servants are obedient to him, whether he is loved by them, and whether he loves his subjects. For the object of ascertaining all these points, O best of kings, I have come to you. Like food to a hungry person, you have become dear to me. I dislike your ministers, however, as a person whose thirst has been slaked dislikes drink. They have found fault with me because I seek your good. I have no doubt that there is no other cause for that hostility of theirs to me. I do not cherish any hostile intentions towards them. I am engaged in only marking their faults. As one should fear a wounded snake, every one should fear a foe of wicked heart!'[1]

"The king said, 'Reside in my palace, O Brahmana! I shall always treat you with respect and honour, and always worship you. They that will dislike you shall not dwell with me. Do you thyself do what should be done next unto those persons (of whom you have spoken). Do you see, O holy one, that the rod of chastisement is wielded properly and that everything is done well in my kingdom. Reflecting upon everything, do you guide me in such a way that I may obtain prosperity.'

"The sage said, ’shutting your eyes in the first instance to this offence of theirs (viz., the slaughter of the crow), do you weaken them one by one. Prove their faults then and strike them one after another. When many persons become guilty of the same offence, they can, by acting together, soften the very points of thorns. Lest your ministers (being suspected, act against you and) disclose your secret counsels, I advise you to proceed with such caution. As regards ourselves, we are Brahmanas, naturally compassionate and unwilling to give pain to any one. We desire your good as also the good of others, even as we wish the good of ourselves. I speak of myself, O king! I am your friend. I am known as the sage Kalakavrikshiya. I always adhere to truth. Your sire regarded me lovingly as his friend. When distress overtook this kingdom during the region of your sire, O king, I performed many penances (for driving it off), abandoning every other business. From my affection for you I say this unto you so that you mayst not again commit the fault (of reposing confidence on undeserving persons). You have obtained a kingdom without trouble. Reflect upon everything connected with its weal and woe. You have ministers in your kingdom. But why, O king, should you be guilty of heedlessness?' After this, the king of Kosala took a minister from the Kshatriya order, and appointed that bull among Brahmanas (viz., the sage Kalakavrikshiya) as his Purohita. After these changes had been effected, the king of Kosala subjugated the whole earth and acquired great fame. The sage Kalakavrikshiya worshipped the gods in many grand sacrifices performed for the king. Having listened to his beneficial counsels, the king of Kosala conquered the whole earth and conducted himself in every respect as the sage directed.'"

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The belief is still current that a wounded snake is certain to seek vengeance even if the person that has wounded it places miles of distance between himself and the reptile. The people of this country, therefore, always kill a snake outright and burn it in fire if they ever take it.

Conclusion:

This concludes Section LXXXII of Book 12 (Shanti Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 12 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.