Satapatha-brahmana

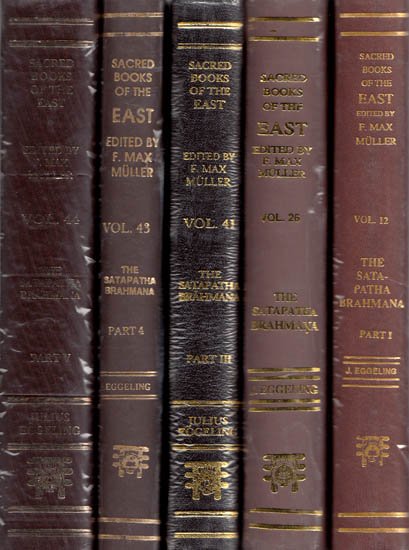

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

This is Satapatha Brahmana VIII.1.3 English translation of the Sanskrit text, including a glossary of technical terms. This book defines instructions on Vedic rituals and explains the legends behind them. The four Vedas are the highest authortity of the Hindu lifestyle revolving around four castes (viz., Brahmana, Ksatriya, Vaishya and Shudra). Satapatha (also, Śatapatha, shatapatha) translates to “hundred paths”. This page contains the text of the 3rd brahmana of kanda VIII, adhyaya 1.

Kanda VIII, adhyaya 1, brahmana 3

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

1. As to this they say, 'What are the vital airs (prāṇa), and what the Prāṇabhṛtaḥ?'--The vital airs are just the vital airs, and the Prāṇabhṛtaḥ (holders of the vital airs) are the limbs, for the limbs do hold the vital airs. But, indeed, the vital airs are the vital airs, and the Prāṇabhṛt is food, for food does uphold the vital airs.

2. As to this they say, 'How do all these (Prāṇabhṛt-bricks) of him (Agni and the Sacrificer) come to be of Prajāpati's nature?'--Doubtless in that with all of them he says, 'By thee, taken by Prajāpati:' it is in this way, indeed, that they all come to be for him of Prajāpati's nature[1].

3. As to this they say, 'As they chant and recite for the cup when drawn, wherefore, then, does he put in verses and hymn-tunes[2] before (the drawing of) the cups?'--Doubtless, the completion of the sacrificial work has to be kept in view;--now with the opening hymn-verse the cup is drawn; and on the verse (ṛc) the tune (sāman) is sung: this means that he thereby puts in for him (Agni) both the verses and hymn-tunes before (the drawing of) the cups. And when after (the drawing of) the cups there are the chanting (of the Stotra) and the recitation (of the Śastra): this means that thereby he puts in for him both the stomas (hymn-forms) and the pṛṣṭha (sāmans) after (the drawing of) the cups[3].

4. As to this they say, 'If these three are done together--the soma-cup, the chant, and the recitation,--and he puts in only the soma-cup and the chant, how comes the recitation also in this case to be put (into the sacrificial work) for him[4]?' But, surely, what the chant is that is the recitation[5]; for on whatsoever (verses) they chant a tune, those same (verses) he (the Hotṛ) recites thereafter[6]; and in this way, indeed, the Śastra also comes in this case to be put in for him.

5. As to this they say, 'When he speaks first of three in the same way as of a father's son[7], how, then, does this correspond as regards the ṛle and sāman?' The sāman, doubtless, is the husband of the

Ṛc; and hence were he also in their case to speak as of a father's son, it would be as if he spoke of him who is the husband, as of the son: therefore it corresponds as regards the ṛc and sāman. 'And why does he thrice carry on (the generation from father to son)?'--father, son, and grandson: it is these he thereby carries on; and therefore one and the same (man) offers (food) to them[8].

6. Those (bricks) which he lays down in front are the holders of the upward air (the breath, prāṇa); those behind are the eye-holders, the holders of the downward air (apāna)[9]; those on the right side are the mind-holders, the holders of the circulating air (vyāna); those on the left side are the ear-holders, the holders of the outward air (udāna); and those in the middle are the speech-holders, the holders of the pervading air (samāna).

7. Now the Carakādhvaryus, indeed, lay down different (bricks) as holders of the downward air, of the circulating air, of the outward air, of the pervading air, as eye-holders, mind-holders, ear-holders, and speech-holders; but let him not do this, for they do what is excessive, and in this (our) way, indeed, all those forms are laid (into Agni).

8. Now, when he has laid down (the bricks) in front, he lays down those at the back (of the altar); for the upward air, becoming the downward air, passes along thus from the tips of the fingers; and the downward air, becoming the upward air, passes along thus from the tips of the toes: hence when, after laying down (the bricks) in front, he lays down those at the back, he thereby makes these two breathings continuous and connects them; whence these two breathings are continuous and connected.

9. And when he has laid down those on the right side, he lays down those on the left side; for the outward air, becoming the circulating air, passes along thus from the tips of the fingers 1; and the circulating air, becoming the outward air, passes along thus from the tips of the fingers[10]: hence when, after laying down (the bricks) on the right side, he lays down those on the left side, he thereby makes these two breathings continuous and connects them; whence these two breathings are continuous and connected.

10. And those (bricks) which he lays down in the centre are the vital air; he lays them down on the range of the two Retaḥsic (bricks), for the retaḥsic are the ribs, and the ribs are the middle: he thus lays the vital air into him (Agni and the Sacrificer) in the very middle (of the body). On every side he lays down (the central bricks)[11]: in every part he thus lays vital air into him; and in the same way indeed that intestinal breath (channel) is turned all round the navel. He lays them down both lengthwise and crosswise[12], whence there are here in the body (channels of) the vital airs both lengthwise and crosswise. He lays them down touching each other: he thereby makes these vital airs continuous and connects them; whence these (channels of the) vital airs are continuous and connected.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Or, come to be (Agni-) Prajāpati's (prājāpatyā bhavanti).

[2]:

In laying down the different sets of Prāṇabhṛt-bricks the priest is said (in VIII, 1, 1, 5; 8; 2, 2; 5; 8) symbolically to put into the sacrificial work (or into the altar, Agni) 'both verses or metres (as Gāyatrī, Triṣṭubh, &c.) and hymn-tunes (as Gāyatra. Svāra, &c.).

[3]:

It is not quite clear whether this is the correct construction of p. 14 the text, especially as, in the paragraph referred to in. the last note, it is not only the metres and tunes that are supposed to be put in along with the Prāṇabhṛtaḥ, but also the stomas and pṛṣṭha-sāmans.

[4]:

Only soma-cups (graha) and hymn-tunes (sāman) and hymn-forms (stoma) are specially named in connection with these bricks, but no śastras.

[5]:

Every stotra, chanted by the Udgātṛs, is followed by a śastra recited by the Hotṛ or one of his assistants.

[6]:

Most chants (stotra) consisting of a single triplet (e. g. the Pṛṣṭha-stotras at the midday service) have their text (stotriyatṛca) included in the corresponding śastra recited by the Hotṛ, or one of the Hotrakas; it being followed, on its part, by the recitation of an analogous triplet (anurūpa, 'similar or corresponding,' i.e. antistrophe) usually commencing with the very same word, or words, as the stotriya.

[7]:

As in the case of the first (south-west) set of bricks, VIII, 1, 1, 4-6, he puts down the first four with 'This one, in front, the existent,' 'His, the existent's son, the breath,' 'Spring, the son of the breath,' and 'The Gāyatrī, the daughter of spring,'--implying three generations from father to son (or daughter). In the formulas of the remaining bricks of each set referring to the metres (or verses, ilk) and hymn-tunes (sāman) the statement of descent is expressed more vaguely by, 'From the Gāyatrī (is derived) the Gāyatra,' &c.

[8]:

At the offerings to the Fathers, or deceased ancestors, oblations are made to the father, grandfather, and great-grandfather; see II, 4, 2, 23.

[9]:

Sāyaṇa, on Taitt. S. IV, 3, 3, explains 'prāṇa' by 'bahiḥsaṃcārarūpa,' and 'apāna' by 'punarantaḥsaṃkārarūpa;' see also part i, p. 120, note 2; but cp. Maitry-up. II, 6; H. Walter, Haṭhayogapradipikā, p. xviii. Beside the fifty bricks called 'Prāṇabhṛtaḥ,' the Taittirīyas also place fifty Apānabhṛtaḥ in the first layer of the altar.

[10]:

? Or, perhaps, the fingers and toes. The same word (aṅguli), having both meanings, makes it difficult exactly to understand these processes. The available MSS. of Harisvāmin's commentary unfortunately afford no help.

[11]:

That is to say, he lays down the fifth set round the (central) Svayamātṛṇṇā, on the range of the two Retaḥsic bricks. It is, p. 17 however, not quite clear in what particular manner this fifth set of ten bricks is to be arranged round the centre so as to touch one another. The two Retaḥsic bricks, occupying each a space of a square foot north and south of the spine, are separated from the central (Svayamātṛṇṇā) brick by the Dviyajus brick a foot square. The inner side of the retaḥsic-space would thus be a foot and a half, and their outer side two feet and a half, distant from the central point of the altar. The retaḥsic range, properly speaking, would thus consist of a circular rim, obtained by drawing two

[12]:

Each special brick is marked on its upper surface with (usually three) parallel lines. Now the bricks are always laid down in such a way that their lines run parallel to the adjoining spine, whence those on the east and west sides have their lines running lengthwise (west to east), and those on the north and south sides crosswise (north to south). As to the four corner bricks there is some uncertainty on this point, but if we may judge from the analogy of the second layer in this respect, the bricks of the south-east and north-west corners would be eastward-lined, and those of the northeast and south-west corners northward-lined.