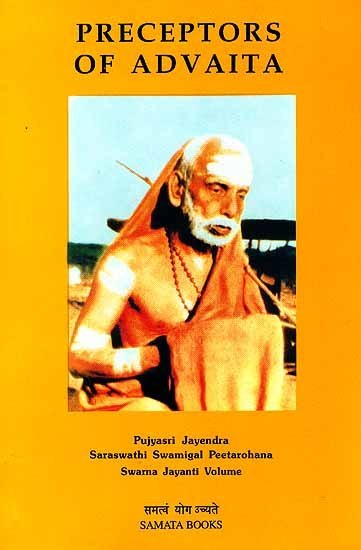

Preceptors of Advaita

by T. M. P. Mahadevan | 1968 | 179,170 words | ISBN-13: 9788185208510

The Advaita tradition traces its inspiration to God Himself — as Śrīman-Nārāyaṇa or as Sadā-Śiva. The supreme Lord revealed the wisdom of Advaita to Brahma, the Creator, who in turn imparted it to Vasiṣṭha....

60. The Sage of Kāñchī

THE SAGE OF KANCHI

by

T. M. P. Mahadevan

M.A., PH.D.

Any one who has read the works of Śrī Śaṅkara would certainly want to know what sort of a person the great Master was. In all his extensive writings he nowhere makes any reference to himself. The only isolated passage where one could see an oblique reference relates, not to any detail in personal biography, but to the inwardly felt experience of the Impersonal Absolute. In this passage which occurs towards the end of the Brahma-sūtra-bhāṣya , he observes:

“How is it possible for another to deny the realization of Brahman -knowledge, experienced in one’s heart, while bearing a body?”[1]

The reference here is to the plenary experience of Brahman, even while living in a body (jīvan-mukti); and it is evident that the testimony offered here is from Śaṅkara’s own experience. The outlines of the story of Śaṅkara’s life could be gathered only from the Śaṅkara-vijayas and other narratives. Inspite of varying accounts in regard to some of the details, the image of the Master that one forms from these sources, taking into account also the grand teachings that are to be found in his own works, is that of a great spiritual leader, who renounced all wordly attachments even as a boy, who was a prodigy in scriptural lore and wisdom, who spent every moment of his life in the service of the masses of mankind by placing before them, through precept and practice, the ideal of the life divine, and who was a teacher of teachers, the universal guru. Even as such a magnificent image is being formed, the doubt may arise in the minds of many : Is it possible that such a great one walked this earth? Is it possible that in a single ascetic frame was compressed several millennia of the highest spiritual human history? This doubt is sure to be dispelled in the case of those who have had the good fortune of meeting His Holiness Jagadguru Śrī Chandra-śekharendra Sarasvatī, the Sixty-eighth in the hallowed line of succession of Śaṅkarāchāryas to adorn the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha of Kāñchī, Anyone who comes into the august presence of His Holiness cannot but recall to his mind the image of Ādi Śaṅkara, the immaculate sage who was divine and yet human, whose saving grace was universal in its sweep, and whose concern was for ail— even for the lowliest and the last. For sixty years Śrī Chandraśekharendra Śarasvatī has been fulfilling the noble spiritual mission entrusted by Ādi Śaṅkara to his successors bearing his holy name. Numerous are the ways in which he has given the lead for human upliftment through inner awakening. When one considers his life of ceaseless and untiring dedication to the task of stabilizing and promoting the renascent spirit of India so that humanity may be benefited thereby, one cannot but conclude that it is the unbounded Grace of Śaṅkara that has assumed this new form in order to move the world one step higher on the ladder to universal perfection.

2. Early Life

‘Chandraśekharendra Sarasvatī’ is the sannyāsa name given to Svāmināthan when he was barely thirteen. It was on the 20th of May, 1894, that Svāmināthan was born in Viluppuram (South Arcot District). His father, Subrahmaṇya Śāstrī, belonged to the Hoysala Karnāṭaka Smārṭa Brahmaṇa family which had migrated years earlier to the Tamil country and had settled in Choḷa-deśa. After passing the Matriculation Examination from the Government School, Kumbhakoṇam, taking the first place, Subrahmaṇya Śāstri served as a teacher for some time, and then entered the Educational Service. At the time of Svāmināthan’s birth, he was at Viḷuppuram. Svāmināthan’s mother, Mahālakṣmī, hailed from a family belonging to Icchaṅguḍi, a village near Tiruvaiyāru. An illustrious and saintly person connected with the family, Raja Govinda Dīkṣita of the sixteenth century, was minister to the first Nāyak King of Tañjāvūr; Dīkṣita popularly known as Ayyan, was responsible for many development projects in Choḷa-territory; his name is still associated with a tank, a canal, etc. (Ayyan Canal, Ayyan Kulam).

Svāmināthan was the second child of his parents. He was named Svāmināthan after the Deity of the family, the Lord Svāminātha of Svāmimalai, Two incidents relating to this early childhood period are recorded by the Āchārya himself in an article contributed to a symposium on What Life Has Taught Me.[2] This is how he has described these incidents:

“A ‘mara nāi’ as they call it in Tamil or teddy cat (an animal which generally climbs on trees and destroys t he fruits during nights) somehow got into a room in the house and thrust' its head into a small copper pot with a neck, which was kept in a sling and contained jaggery. The animal was not able to pull out its head and was running here and there in the room all through the night. People in the house and neighbours were aroused by the noise and thought that some thief was at his job. But, the incessant noise continued even till morning hours, and some bravados armed with sticks opened the door of the room and found the greedy animal. It was roped and tied to a pillar. Some experienced men were brought and after being engaged in a tug-of-war, they ultimately succeeded in removing the vessel from the head of the animal. The animal was struggling for life. It was at last removed to some spot to roam freely, I presume. The first experience of my life was this dreadful ocular demonstration born of greed causing all our neighbours to spend an anxious and sleepless night.

The next experience was a man in the street who entered into the house seeing me alone with tiny golden bangles upon which he began to lay his hands. I asked him to tighten the hooks of the bangles which had become loose and gave a peremptory and authoritative direction to him to bring them back repaired without delay. The man took my orders most obediently and took leave of me with the golden booty. In glee of having arranged for repairs to my ornament, I speeded to inform my people inside of the arrangement made by me with the man in the street who gave his name as Ponnusvāmi. The people inside hurried to the street to find out the culprit But the booty had become his property true to his assumed name, Ponnusami (master of gold)”

Reflecting on these experiences, the Āchārya observes with characteristic humility:

“I am prone to come to the conclusion that there lives none without predominantly selfish motives. But with years rolling on, an impression, that too a superficial one true to my nature, is dawning upon me that there breathe on this globe some souls firmly rooted in morals and ethics who live exclusively for others voluntarily forsaking not only their material gains and comforts but also their own sādhana towards their spiritual improvements”.

A significant incident occurred in the year 1899. Svāmināthan’s father was then serving as a teacher at a school in Porto-novo. He took the boy to Chidambaram for the Kumbhābhiṣekam of Ilaimaiyākkinār temple. Ilaimaiyākkinār it was that, according to a legend, gave salvation to Tirunīlakaṇthanāyanār, one of the sixty-three Śaiva saints whose biographies constitute the theme of Śekkilār’s Periyapurānam. The father and son reached Chidambaram one evening and stayed at the house of Śrī Venkatapati Aiyar, an Inspector of Schools. Svāmināthan was asked by his father to go to sleep after being assured that he would be woken up at night, and taken to the temple to see the procession and have the darśan of the Deity. Svāmināthan woke up only next morning, and felt that his father had disappointed him very much by not waking him up at night and taking him to the temple. He gave expression to his feeling of disappointment to his father. The latter consoled him saying that he himself had not gone to the temple, and added that it was very fortunate that none in the house had gone there. There was a fire accident that night at the temple and many of those who were inside the temple perished in that great fire. On the same night, Svāmināthan’s mother at Porto-novo had dreamt of the fire accident at the Chidambaram temple, and in the early hours of the next day she was very much perturbed imagining that danger might have befallen her husband and child. In a fit of frenzy she came out of the house only to be fold by her servant-maid that there had been a gruesome fire accident at the Chidambaram temple. She proceeded towards the railway station to enquire from the people who were returning from Chidambaram about her husband and her son. Her joy knew no bounds when she saw both of them coming out of the railway station. The agony she had experienced in her dream the previous night, and the providential manner in which the father and son were saved from the tragedy should have had some mysterious connection.

In the year 1900, Svāmināthan was in the first' standard in school at Chidambaram, Śrī M. Singaravelu Mudaliyār, the Assistant Inspector of Schools, visited the school on an inspection and discovered in t he boy the makings of a genius. He asked him to read the Longman’s English Reader prescribed for a higher standard; and Svāmināthan read it remarkably well. At his instance Svāmināthan was promoted to the third standard.

The upanayanam of the boy was performed in 1905 at Tinḍivanam to which place Subrahmanya Śāstri had been transferred. It is significant that the Sixty-sixth Śaṅkarāchārya of Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha, Śrī Chandraśekharendra Sarasvatī, who was at the time touring in South Arcot District, sent his blessings: and it was he that later on literally captivated the boy, and chose him as successor to the holy seat: and it is also significant that Svāmināthan came to bear the sannyāsa name of the Sixty-sixth Āchārya.

When Svāmināthan was ten years of age, he was admitted in the Second Form in the Arcot American Mission School, Tiṇḍi-vanam. The prodigy that the boy was, he gave an excellent record of himself at school. He used to carry away many prizes, including the one for proficiency in the Bible studies. The teachers of the school naturally took a great liking for Svāmināthan: they were proud of him and cited him to the other boys as a model student.

In 1906, when Svāmināthan was studying in the Fourth Form, the school was arranging for a dialogue from Shakespeare’s King John, The teachers who were responsible for fixing the participants in the dialogue could not' find a suitable candidate from the age-group fixed for taking on the role of Prince Arthur, the central character in the play. The Head-Master who knew Svāmināthan’s extraordinary talents sent for the boy who was only twelve then and assigned the role to him. After obtaining permission from his parents, Svāmināthan rehearsed his part for only two days, and acquitted himself remarkably well as Prince Arthur in the dialogue winning the appreciation of the entire audience: the acting was so perfect and the enunciation of Shakespeare’s classical English so accurate. One of Svāmināthan’s friends had lent’ him the attire of a prince and Svāmināthan really looked a prince. Many of the teachers went to Subrahmaṇya Śāstri’s house next day and expressed how greatly they were pleased with Svāmināthan’s superb performance.

3. Ascension to Sri Kamakoti Pitha

We have already referred to the Sixty-sixth Āchārya of Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha, Śrī Chandraśekharendra Sarasvatī. In 1900 he was camping in the village Perumukkal near Tiṇḍivanam and was observing the chāturmāsya-vrata there. Subrahmaṇya Śāstri went to that village along with his family to have the Āchārya’s darśana and receive his blessings. Svāmināthan saw His Holiness from a distance in a temple during the viśvarūpa-yātrā.

His Holiness the Sixty-sixth Āchārya had the Navarātrī Celebrations performed at Marakkanam village. After the Navarātrī he was camping at Sāram village situated on the Tiṇḍivanam-Madurantakam rail route. Svāmināthan went there with a friend without informing his parents. He offered his homage at the lotus-feet of His Holiness and requested his permission to leave. His Holiness insisted that Svāmināthan should stay there itself. Two pandits attached to the Maṭha also asked Svāmināthan to stay there. But Svāmināthan said that he had to attend school and that he had not informed his parents about his coming over to the Maṭha. Thereupon His Holiness gave him permission to leave. Svāmināthan left for Tiṇḍivanam in a cart belonging to the Maṭha. After Svāmināthan had left, His Holiness informed the two pandits of the Maṭha his keen desire to install Svāmināthan as his successor to t he glorious pontifical seat of Kāñchī.

His Holiness the Sixty-sixth Āchārya attained siddhi at Kalavai and Svāmirāthan’s maternal cousin was installed as the Sixty-seventh Āchārya. He was the only child of Svāmināthan’s mother’s sister. And, he had lost his father when he was quite young. He studied the Vedas at Chidambaram, staying in Svāmināthan’s family in the years 1900-1901. After that he was staying along with his mother in the Maṭha itself. When Svāmināthan’s parent’s received the news about his installation to the Pīṭha, Svāmināthan’s mother desired to see and console her sister whose only child had become an ascetic. The whole family planned to leave for Kalavai in a cart. But at the last minute, Svāmināthan’s father received a telegram from Tiruchi asking him to attend an Education Conference at Tiruchi. And so, before leaving for Tiruchi, he desired the members of his family not to go to Kalavai in the cart because it was not quite safe to travel

HIS HOLINESS SRI CHANDRASEKHARENDRA SARASVATI [when thirteen years old.]

nearly fifty miles in a cart without proper escort; he asked them to go to Kāñchī by train and from there to Kalavai in a cart.

The epic journey to Kāñchī and Kalavai and the providential manner in which Svāmināthan came to be installed as the Head of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha at a very tender age is recounted by the Āchārya himself in the article What Life Has Taught Me already referred to, in the following words:

“In the beginning of the year 1907, when I was studying in a Christian Mission School at Tiṇḍivanam, a town in the South Arcot District, I heard one day that the Śaṅkarāchārya of Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha who was amidst us in our town in the previous year, attained siddhi at Kalavai, a village about ten miles from Arcot and twenty-five miles from Kāñchīpuram. Information was received that a maternal cousin of mine who, after some study in the Ṛg Veda had joined the camp of the Āchārya offering his services to him, was installed on the Pīṭha.

He was the only son of the widowed and destitute sister of my mother and there was not a soul in the camp to console her. At this juncture, my father who was a supervisor of schools in the Tiṇḍivanam taluk, planned to proceed with his family to Kalavai, some sixty miles from Tiṇḍivanam in his own touring bullock cart. But on account of an educational conference at Trichinopoly he cancelled the programme.

My mother with myself and other children started for Kalavai to console her sister on her son assuming the sannyāsa āśrama. We travelled by rail to Kāñchīpuram and halted at the Śaṅkarāchārya Maṭha there. I had my ablution at the Kumara-koṣṭa-tīrtha. A carriage of the Maṭha had come there from Kalavai with persons to buy articles for the Mahā Pūjā on the 10th day after the passing away of the late Āchārya Paramaguru. But one of them, a hereditary maistry of the Maṭha asked me to accompany him. A separate cart was engaged for the rest of the family to follow me.

During our journey, the maistry hinted to me that I might not return home and that the rest of my life might have to be spent in the Maṭha itself! At first I thought that my elder cousin having become the Head of the Maṭha, it might have been his wish that I was to live with him. I was then only thirteen years of age and so I wondered as to what use I might be to him in the institution.

But the maistry gradually began to clarify as miles rolled on that the Āchārya my cousin in the pūrvāsrama, had fever which developed into delirium and that was why I was being separated from the family to be quickly taken to Kalavai. He told me that he was commissioned to go to Tiṇḍivanam itself and fetch me but he was able to meet me at Kāñchīpuram itself. I was stunned with this unexpected turn of events. I lay in a kneeling posture in the cart itself, shocked as I was, repeating RĀMA RĀMA, the only spiritual prayer I knew, during the rest of my journey.

My mother and the other children came some time later only to find that instead of her mission of consoling her sister, she herself was placed in the state of having to be consoled by someone else!”

Permission for installing Svāmināthan in the great pontifical seat of Kāñchī was obtained from his father through telegram and every arrangement was made as quickly as possible tor his installation. Svāmināthan ascended the Śrī Kāñchī Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha on the 13th of February, 1907, as the Sixty-eighth Āchārya, assuming the sannyāsa name ‘Chandraśekharendra Sarasvatī.’ His Holiness went in a procession to the siddhisthala and performed the mahā-pūjā of the Sixty-sixth Āchārya.

From Kalavai the new Āchārya proceeded to Kumbhakoṇam where the headquarters of the Maṭha were located. The transfer of the headquarters from Kāñchī to Kumbhakoṇam had been necessitated by the unsettled political conditions in Tonḍaimaṇḍalam in the eighteenth century during the time of the Sixty-second Āchārya. With the passage of time the responsibilities and the functions of the Maṭha increased. It is not a simple monastic institution. The Maṭha has to administer properties endowed for various religious and philanthropic purposes. The headship of such an organization, it is obvious, should be extremely difficult. The administration requires on the part of the Āchārya great spiritual power coupled with worldly wisdom, the ability to fill the status of the Jagadguru , as well as minute knowledge of men and matters. It is pertinent to mention here that the paternal grand-father of Svāmināthan, Gaṇapati Śāstrī, was closely connected with the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha as its manager (sarvādhikārī) for over fifty years from 1835 onwards. It was under his stewardship that permanent arrangements were made for adequate sources of income to meet the expenses of the Maṭha. The duties of the Maṭha had enormously increased since then. And, the new Āchārya lost no time in getting himself equipped for the tasks awaiting him. For this, he had first to go to the headquarters at Kumbhakoṇam.

Leaving Kalavai in the same year, i.e. 1907, the Āchārya went to Kumbhakoṇam after making a brief halt at Tiṇḍivanam. One could well imagine what a proud day it should have been for the people of Tiṇḍivanam when they received their own Svāmināthan as the new Āchārya of Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha. The town wore a festive appearance. The teachers of the American Mission School and the former school-fellows vied with one another in meeting the Āchārya and conversing with him. The Āchārya had a good word for every one, and spoke tenderly to each one of the teachers. After three days’ stay at Tiṇḍivanam, the Āchārya resumed the journey and reached Kumbhakoṇam in the month of Chitra in the year Plavaṅga.

The head of an Āchārya-Pīṭha is looked upon by the disciples as the spiritual ruler, and is invested with all the regalia associated with a king. The disciples of the Maṭha desired to celebrate the installation of the new Āchārya as the head of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha with due ceremony. The installation was performed on a grand scale on Thursday the 9th of May 1907 at the Kumbhakoṇam Maṭha. Her Highness Jeejambabhai Saheb and Her Highness Ramakumarambha-bhai Saheb, queens of Shivaji of the ruling family of Tanjore sent all the regal paraphernalia for the coronation. The ceremonial abhiṣeka was performed with jasmine flowers. First, the representatives of the Bangāru Kāmākṣī, Kāmākṣī and Akhilāṇḍeśvarī temples performed the abhiṣeka. This was followed by the representatives of the princely family of Tanjore, of the various Zamindars, and of the several aristocratic families. Prominent scholars took an active part in the coronation. Seated on the throne of the Maṭha, the Āchārya blessed all the people assembled there. That night seated in the golden ambāri on the regal elephant, sent by the Tanjore ruling family, His Holiness went in a grand procession through the main streets of Kumbhakoṇam. Thus commenced the Āchārya’s spiritual rulership as the Jagadguru.

4. The First Tour of Victory (Vijaya-yatra)

Tours of victory (viiaya-yātrā) , in the present context, mean the journeys undertaken by the Āchārya to the different parts of the country to bless the people by his presence, to give them opportunities for participation in the daily pūjā performed to Śrī Chandramaulīśvara and Tripurasundarī (Parameśvara and Pārvatī), the presiding deities of the Maṭha, and to impart to them the light of spiritual knowledge and the guidelines for conduct. Wherever the Āchārya goes, the people of that place take the fullest advantage of his presence, celebrate the event as a great festival, listen to his soul-moving discourses in pindrop silence, and find in the very atmosphere a sense of exaltation.

The first tour undertaken by the new Āchārya was to Jambukeśvaram (Tiruvānaikkā) in 1908. It was here that Ādi Śaṅkara had adorned the Image of the Goddess Akhilāṇḍeśvarī with ear-ornaments (tāṭaṅka). In 1908 arrangements were made for the Kumbhābhiṣekam of the temple there, after it had been renovated. Our Āchārya was invited by the temple Sthānikas and the authorities to grace the occasion with his presence. The Kumbhābhiṣekam was performed with all solemnity and grandeur. Śrī Sachchidānanda Śivābhinava Narasiṃha Bhāratī, Śaṅkarāchārya of Śṛṅgeri, visited the Temple a day after the Kumbhabhiṣekam was performed. Śrī Subrahmanya Bhāratī, Śaṅkarāchārya of Śivagaṅga, visited the shrine a few months later.

From Jambukeśvaram, our Āchārya proceeded to Ilaiyāttaṅkuḍi in Rāmanāthapuram District, the place where the Sixty-fifth Āchārya of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha, Śrī Mahādevendra Sarasvatī, had attained siddhi. On the way, he visited Pudukkoṭṭai, and stayed there for some days. At Ilaiyāttaṅkuḍi he offered his homage to his illustrious predecessor at the Adhiṣṭhānam. From there he returned to Jambukeśvaram for his chāturmāsya. At the end of the period, he went back to Kumbhakoṇam after a brief halt at Tañjāvūr. 1909 was the Mahāmakha year at Kumbhakoṇam — an event which occurs every twelfth year. The Maṭha did its part in playing host to the pilgrims. On the day of the festival, it was a feast for the eyes to see the Āchārya go for the ceremonial bath in the Mahāmakha tank. In a grand procession he went, seated in an ambāri on the back of an elephant.

Our Āchārya was only fifteen years old in 1909. For two years, the learned paṇḍitas of the Maṭha imparted to him instruction in Samskrit classics at Kumbhakoṇam itself. The management of the Maṭha felt that a less congested place than Kumbhakoṇam — a place which would not be frequented by visiting crowds — would be more suitable for study. Mahendramangalam, a quiet village on the northern bank of the Akhaṇḍa Kāverī, was selected for the purpose; a parṇaśālā was put up near the edge of the river. From 1911 to 1914, the Āchārya stayed there studying and receiving the requisite training. It was a strange relation between the teachers and the taught. The teachers were the disciples of the Maṭha. The Āchārya showed the utmost consideration for and respect to the teachers who were entrusted with his training; they too were conscious of the unique honour that was theirs.

Whenever experts in and exponents of musicology met him, he sought to improve his knowledge of this science and art through conversations with them. He used to snatch time to visit the nearby islands in the Kāverī to marvel at the natural scenery. Photographers sometimes took photographs of the natural surroundings. The Āchārya evinced interest in the photographic art. Some of the other areas of study of which he gained intimate knowledge are mathematics and astronomy.

In 1914 the Āchārya returned to the Maṭha at Kumbhakoṇam. He was twenty then. He had acquired by then encyclopaedic knowledge. Whenever scholars went to him, he used to put searching questions relating to their respective fields of study, and thereby gain a lot of information. When he was studying in Kumbhakoṇam, he made it a point to pay an annual visit to Gaṅgaikoṇḍa-choḻa-puram, and study the inscriptions to be found there and the niceties of temple-architecture. Thus, in a variety of ways the Āchārya equipped himself with the all-round knowledge and ability required for fulfilling the obligations of the leadership of the Kāmakōṭi Pīṭha.

Since the Āchārya had not reached the age of majority, the Maṭha was managed under the direction of the Court of Wards from 1911 to 1915. When the Āchārya completed twenty-one years of age in May 1915, he took over the management of the Maṭha under his direct supervision. But the actual execution of the affairs of the Maṭha was by duly appointed officers and agents. Even in the papers granting power of attorney to the agents, the Āchārya would not sign—this is in accordance with custom and usage. Only the official seal of the Maṭha would be affixed.

The Śaṅkara Jayantī Celebrations that year were performed on a grand scale. A new journal ‘Arya-dharma’ commenced its publication under the auspices of the Maṭha. In October 1916, the Navarātrī festival was observed at the Maṭha with a new fervour. The poet Subrahmanya Bhāratī wrote in one of his essays praising, in the highest of terms, the manner in which the festival was conducted in the Maṭha. This is the annual festival at which worship is offered to the World-Mother in Her triple manifestations—as Durgā, Lakṣmī, and Sarasvatī. Learned paṇḍitas came from all over the country to participate in the sadas . The foremost exponents of music gave concerts in the presence of the Āchārya. At the conclusion of the festival on the night of the tenth day, the Āchārya went round the town at the head of a huge and colourful procession.

Some of the very first measures taken by the Āchārya for the promotion of classical learning and of social welfare yielded rich results and marked only the beginning of many more to come. Distinguished scholars were honoured by the award of titles such as ‘śāstraratnākara’. Essay-competitions were held for college students on subjects relating to our dharma. Free studentships were instituted for the benefit of deserving students in schools and colleges. A free Ayurvedic dispensary was started in the Maṭha. During the Āchārya’s stay in Kumbhakoṇam from 1914 to 1918, almost every evening there were learned assemblies or music concerts. Paṇḍitas and śaṅgīta-vidvāns yearned for the Guru’s grace. Even professors, scientists, engineers, and administrators went to him for guidance and encouragement. The followers of the other faiths found in the Āchārya a deep understanding of their respective doctrines and profound appreciation of every type and grade of spiritual endeavour. Everyone who came into contact with the Āchārya recognized in him the Jagadguru.

6. All-India Tour (1919-1939)

The Āchārya’s great tour of our sacred land commenced in March 1919. It was a long and strenuous tour; but it was supremely worthwhile because of the opportunities it gave to people all over the country to meet the Āchārya and receive his blessing. The Āchārya never uses any of the modem modes of transport. He mostly walks, and accepts the use of a palanquin only when it is absolutely necessary. An entourage accompanies him, consisting of the officials of the Maṭha, paṇḍitas, vaidikas, servants, and animals such as cows, elephants, etc. Wherever the Āchārya camps, lots of devotees gather and stay at the camp as long as they can in order to derive the utmost advantage from the Holy Presence. Besides the daily anuṣṭhāna and pūjā, meeting the devotees, receiving visitors, giving instructions to the people concerned for the conduct of the affairs of the Maṭha and of the manv religious and welfare organizations occupy the Āchārya’s time each day. He hardly gets two or three hours of rest out of twenty-four. With frugal diet taken in between fasting days, and with so much of pressing work day after day, it is a marvel how the Āchārya meets the demands on his time and attention with absolute serenity and with perfect poise. No one will fail to nofe that the ideal of the sthita-prajña (the sage who has gained s t eady wisdom) has become actual in the soul-elevating person of the Āchārya.

The long pilgrimage began, as we have seen, in March 1919. During the first three years, the Āchārya visited all the places of pilgrimage—even remote and out of the way villages—in the Tañjāvūr District, the District in which Kumbhakoṇam is situated. The chāturmāsya in 1919 was in Veppattūr village at a distance of five miles to the east of Kumbhakoṇam. During the chāturmāsya, the sannyāsins are to stay at one place so that no harm may be caused to insects and other creatures by treading on them when they come out of the ground in the rainy reason. The sannyāsins camp at one place for four fortnights (pakṣas); this observance starts on the full-moon day in the month of Āṣāḍha which is dedicated to the worship of the sage Vyāsa, the author of the Brahma-sūtra. The day affords an occasion to the devotees to visit the Āchārya’s camp and offer to him their obeisance.

In 1920, on the most auspicious occasion of the mahodaya, the Āchārya took the ceremonial bath in the sea at Vedāraṇyam. The Vyāsapujā and chāturmāsya that year were observed in Māyavaram. One day, during the Āchārya’s stay at this place, a blind old Muslim gentleman wanted to meet the Āchārya. When the permission was given, the old Muslim’s joy knew no bounds. At the command of the Āchārya, he expounded the essential principles of Islam to the assembled audience. And, before taking leave he said that in the person of the Āchārya he found God Himself.

In 1921, there was the Mahāmakham festival in Kumbhakoṇam. The Āchārya who was touring in the neighbourhood went to Kumbhakoṇam on the festival day, but not to the Maṭha, for according to rule he could return to the Maṭha only after completing the vijaya-yātrā. A number of Congress volunteers helped in the orderly conduct of the festival. There was a contingent of Khilafat volunteers also. They went to Paṭṭīśvaram to pay their respects to His Holiness. The Āchārya spoke in appreciative terms about their services and blessed them. One of the leading nationalists of the day, Subrahmaṇyaśiva, met the Āchārya at his Paṭṭīśvaram camp, and asked for his benediction for the liberation of the Motherland from foreign rule and for the spread of devotion to God among the people. The Āchārya readily gave his benediction and said that those laudable objectives would be fulfilled. It may be mentioned here that right from the year 1918 when the Khādi movement came into prominence, the Āchārya has been wearing Khādi.

During this tour of the Tañjāvūr District, the Āchārya was one day going from one village to another, when he saw about two hundred Harijans waiting for his darśana, after having bathed, putting on clean clothes and wearing vibhūti on their foreheads. The Āchārya spent sometime with them, made kind enquiries about their welfare, and gave them new clothes. Similar events have occurred very often during the Āchārya’s journeys. His concern for the poor is great and unlimited, and he never fails to exhort the better-placed sections of society to go to their succour, and asks the Maṭha to set an example in this direction. The Āchārya visited Rāmeśvaram and collected a small quantity of sand for consigning it later on in the waters of the Gaṅgā, which act. is symbolic of the spiritual unity of India.

After touring in the districts of Rāmanāthapuram, Madurai, and Tirunelvēli, the Āchārya went to Jambukeśvaram. This time it was for the tāṭaṅka-pratiṣṭhā. Mention has been made of the Āchārya’s earlier visit to this sacred place in 1908, and of the fact that the Image of Akhilāṇḍeśvarī bears the tāṛaṅkas consecrated by Ādi Śaṅkara. In those early times, according t o legend, the Image was manifesting the Goddess’s fierce aspect. Śaṅkara changed this stale of affairs and enabled the beneficent aspect to express itself by adorning the Image with a pair of ear-ornaments (tiāṭaṅkas) made in the shape of Śrī-chakra. When the ornaments fall into disrepair periodically, they are set right and refixed. This task is the sacred responsibility of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha; and it is the Head of the Pīṭha that has the ornaments re-fixed. In 1846, the then Āchārya of the Pīṭha had this ceremony performed. Now, again, in 1923, arrangements were made for the refixing of the tāṭaṅkas. Our Āchārya went to Jambukeśvaram for participation in this function. It was a great occasion for devotees to gather and pay their homage. Every detail of the ceremony was attended to with meticulous care. Opportunity was availed of for declaring open the renovated Maṭha of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha there. A Veda-pāṭhaśālā and centre for scriptural learning started functioning at the Maṭha. It is interesting to note that the late Sir M. Viśveśvarayya of Mysore said at a meeting in Tiruchi when he visited that town in 1923, that it was at the Kāmakoṭi Maṭha in Jambukeśvaram that he had his upanayanam performed.

After the tāṭaṅka-praṭiṣṭhā ceremony, the Āchārya resumed his journey. One of the places he immediately visited was Nerūr where the Adhiṣṭhāna of Sadāśiva-brahmendra is situated. Born in Tiruvisainallūr near Kumbhakoṇam, Sadāśiva-brahmendra soon became a jīvanmukta, roamed about on the banks of the Kāverī as an avadhūta, and showered his blessings on several people of his time, Śrī Paramaśivendra Sarasvatī was his vidyā-guru. Sadāśiva has written many Advaita works, and has also composed devotion-filled kīrtanas. Our Āchārya spent several hours each day in the Adhiṣṭhāna of Sadāśiva-brahmendra during the time he spent in Nerūr, quietly contemplating on the many benefits that had accrued as a result of Sadāśiva-brahmendra’s exemplary life and precious teachings.

After Nerūr, the Āchārya was camping in the village Kuḻumaṇi near Tiruchi. One day, a prominent gentleman of Tiruchi, Sri F. G. Natesa Aiyar, who had himself lived twenty years of his life earlier as a convert to Christianity, brought along with him a young man form Kerala who had gone to Tiruchi with the intention of getting himself converted to the Christian faith. The Āchārya engaged the young man in conversation on that day as well as on the subsequent few days. He explained to the youth the essentials of Hindu-dharma. It was all-comprehensive; the spiritual paths taught in the other religions were all to be found in Hinduism. It had its own additional advantages. There was no reason whatsoever for any one to leave Hinduism and embrace any other faith. The young man from Kerala was thoroughly convinced of the excellence of the faith he was born in; and he went back home revoking his earlier resolve.

The Āchārya’s visit to different places in Cheṭṭināḍu and Pudukkoṭṭai State lasted about a year. During this period, many paṇḍitas, political workers, and nationalist leaders met the Āchārya and received his blessings. In 1925, Dr U. V. Swāminātha Aiyar, the world-renowned scholar in Tamil, was awarded the title ‘Dākṣiṇātya-kalānidhi’. In those days whenever he happened to be near the camp, he would witness the pūjā performed by the Āchārya. Recalling an earlier experience of his, he said once,

“When I was eighteen years old, I met the Sixty-fifth Āchārya, Śrī Mahādevendra Sarasvatī and watched his unique Śiva-pūjā. It is the same experience I am now having again”.

During the Āchārya’s Cheṭṭināḍu visit, a great Śiva-bhakta, Vaināgaram Rāmanāthan Cheṭṭiyār similarly enjoyed attending the pūjā , and meeting the Āchārya. The people of Cheṭṭināḍu organised a grand procession at Kaḍiyāpaṭṭī. During the procession the Āchārya looked out for Rāmanāthan Cheṭṭiyār, but he could not be seen. At the conclusion of the procession, the Āchārya enquired as to where Cheṭṭiyār was. Cheṭṭiyār who was standing at a distance in the crowd responded. Asked as to why he was not to be found in the procession, he replied with great elation that he had had the privilege that night of being one of the Āchārya’s palanquin-bearers. Another eminent scholar who was honoured by the Āchārya during his sojourn in Cheṭṭināḍu was Śrī Paṇḍitamaṇi M. Kadireśan Cheṭṭiyār who was proficient in both Tamil and Samskrit. The Āchārya and Paṇḍitamaṇi exchanged views about the ancient classical Tamil texts as also about the measures that were needed for promoting the study of Tamil and Samskrit.

Among the politicians and nationalist leaders who met the Āchārya during this period were: Śrī C. R. Dās, along with Sri S. Satyamurti and Sri A. Rangaswami Aiyangar, and Sri Jamnalal Bajaj along with Sri C. Rajagopalachan, and others. The latter group met the Āchārya in 1926 at Jambukeśvaram. Sri C. Rajagopalachari was staying out, sending in Śrī Jamnalal Bajaj. The Āchārya sent for Sri C. Rajagopalachari and asked him why he had not come in. When the latter replied that the reason was that he had not bathed that day, the Āchārya told him that those who were engaged in national work might no t find the necessary time for daily bath, etc., and that Sri C. Rajagopalachari who had dedicated his life for the service of the nation could meet him at any time, and in any condition. The Āchārya made it clear to the politicians and political leaders that he, as a sannyāsin, would not identify himself with party politics of any brand; but he was free to ask them all to keep the good of the people always at heart and to work towards its achievement, and also to do all they could to strengthen faith in God.

An incident which occurred in 1926 deserves special mention. The Āchārya was proceeding to Paṭṭukkoṭṭai from Karambakkuḍi. Among the people who saw the Āchārya off at the latter place there were some Muslims also. One of the Muslims followed the party, touching the palanquin with his hands as a mark of respect. After about three miles of the journey, the Āchārya stopped, and called for the Muslim gentleman and made kind enquiries. The Muslim placed before the Āchārya some personal matters for his advice and guidance, and then offered some verses of praise he had composed along with flowers and fruit. At the command of the Āchārya, the Muslim read out those verses and explained their meaning also. When taking leave he expressed his joy in these words :

“To my eyes the Āchārya appears as the embodiment of Allah Himself. The Āchārya’s darśana is enough for a man who wants to get liberation from worldly bondage.”

In July 1926, the Āchārya went to Uḍaiyārpālaiyam, a Zamindāri closely associated with the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha. When the transfer of the headquarters of the Maṭha from Kānchī to Kumbhakoṇam was being made in the eighteenth century, the then chief of the Zamindārī had rendered all assistance to the Sixty-second Āchārya. Since that time the ruling family had been closely associated with Kāñchī and Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha. Hence, it was a great occasion for Uḍaiyārpālaiyam when our Āchārya visited it in 1926. The Zamindar, his family, and the people accorded to the Āchārya a magnificent reception, and valuable presents were made to the Maṭha to mark the occasion.

When the Āchārya was camping at Tiruppādirippuliyūr, an old lady who was a scholar in Tamil, and national worker came for his darśana. Achalāmbikai was her name. She had composed a narrative poem on the life of Mahātmā Gāndhi. She had known the Āchārya as a child in his pūrvāśrama; and had also studied under the Āchārya’s father. Tears of joy streamed from her eyes when she now beheld the son of her teacher shine as the Jagadguru.

There is a place called Vaḍavāmbalam on the northern bank of South Peṇṇār where a Pūrva Āchārya of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha had his samādhi. At our Āchārya’s wish the samādhi which had been obliterated was reconstructed, and arrangements were made for regular worship there.

At Pondicherry, the officials of the French Government and the people gave the Āchārya a royal welcome. During his stay there, the shocking news of the destruction of the famous temple-car at Tiruvārūr as a result of incendiarism arrived. The āstikas of the district of Tañjāvūr rose as one man and resolved to build a new car. The Āchārya blessed the effort; and through his blessing a new car equalling the old in magnificence was built in two years’ time. One Eḻulūr Subbarāya Vādhyār took a leading part in this laudable effort. Later on, he became a sannyāsin bearing the name ‘Śrī Nārāyaṇa Brahmānanda’; even as a sannyāsin he did great service in renovating old temples and performing kumbhābhi-shekams.

In March 1927, the Āchārya went to Salem and toured in the district. At Erode, a Muslim gentleman offered a few verses in Samskrit which he had composed in praise of the Āchārya. The letters of the verses were written in small squares which together formed the figure of the Śiva-liṅga. In the presence of the Āchārya, the Muslim scholar read out the verses and explained their meaning. When the Āchārya asked him as to how he had mastered the language to such an extent as to be able to compose verses, he replied that his forbears were scholars in Samskrit, and that he himself had studied the language under his own father. The Āchārya complimented him on the proficiency he had attained in Samskrit and advised him to keep up his studies.

After visiting Coimbatore in April 1927, the Āchārya, arrived in Pālghāṭ in the first week of May. Kerala which had given birth to Ādi Śaṅkara was now jubilant at the visit of an illustrious successor in whose life and mission the greatness of the Ādi-Guru was luminously reflected. The Āchārya spoke to the śiṣyas in Malayālam. The people who listened to him mistook him for a Keralīya. It was during the Āchārya’s Pālghāṭ visit that Śrī T. M. Kṛṣṇaswami Aiyar, a leading Advocate of Madras who later served as Chief Judge of Travancore, met the Guru with a party of devotees and conducted Tiruppugaḻ Bhajana. The Āchārya was greatly pleased with the devotion and the music, and blessed the leader by conferring on him the title Tiruppugaḻ-maṇi’.

In the latter half of 1927, Mahātmā Gāndhi was touring the South. He had heard about the Sage of Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha, and wanted very much to meet him. The meeting took place at Nallicheri in Pālghāt They met in a cattle-shed in the Āchārya’s camp. It was a unique experience for the Mahātmā. Here was an authentic successor of Ādi Śaṅkara, dressed in a piece of ochre cloth made of Khādi, and seated on the floor. The Āchārya too appreciated the occasion provided for getting to know at first hand the leader of the nation who had adopted voluntarily the mode of a simple peasant’s life. The Āchārya conversed in Samskrit, and the Mahātmā in Hindi. The conversation took place in a most cordial atmosphere. On taking leave of the Āchārya, the Mahātmā gave expression to the immense benefit he had derived from this unique meeting. How profoundly he was drawn to the Āchārya will be evident from a small incident that occurred during the interview. It was 5-30 in the evening. Śrī C. Rajagopalachari went inside the cattle-shed and reminded the Mahātmā about his evening meal; for the Mahātmā would not take any food after 6 O’clock. The Mahātmā made this significant observation to Śrī C. Rajagopalachari:

“The conversation I am having now with the Āchārya is itself my evening meal for to-day.”

The Āchārya visited several places in Kerala, including Guruvāyūr, Tiruchūr, Ernākulam, Quilon, and Trivandrum. The States of Cochin and Travancore accorded to the Āchārya the highest veneration. At Allepy the Āchārya paid a visit to the Śrī Chandraśekharendra Pāṭhaśālā, and blessed the pupils of the school. At Cape Comorin, he worshipped at the Kanyā Kumārī temple after a bath in the confluence of the seas. After completing the Kerala tour, he proceeded northwards again. At Madurai, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru of Allahabad met the Āchārya and sought his blessings for the effort he was making to convene an All Parties’ Conference, in order to impress on the British Government that it should not ignore the demands of the nationalist forces. The Āchārya told Sir Sapru that the urgent need in India was for achieving the good of the people through peaceful means, and that any effort in that direction had his good wishes.

In February 1929. the Āchārya began his tour of the South Arcot District. The chāturmāsya, that year was observed in Maṇalūrpeṭṭai. For about a month the Āchārya was having fever. In utter neglect of the state of his body, he performed the daily worship, taking his usual bath. In due course the fever left, relieving the devotees of their great anxiety.

During the present tour, the Āchārya was passing through Taṇḍalam village. A cowherd of that place wanted to sell his small holding and give the proceeds as his offering to the Āchārya. The Āchārya dissuaded him from doing so; but the devotee would not go back on his resolve. He actually sold his piece of land to a rich man of the place and made his heart-offering to the Āchārya. The Āchārya, however, did not like that the cowherd should become a destitute. He, therefore, arranged through the local Tahsildar for the allotment of sufficient piece of puramboke land to the cowherd.

In December 1929, the Āchārya went to Tiruvaṇṇāmalai for the Dīpam festival. Tiruvaṇṇāmalai is one of the most sacred places of pilgrimage. The holy hill Aruṇāchala is itself worshipped as a Śiva-liṅga. According to Purāṇa it was here that the Lord Śiva appeared as a column of light whose top and bottom Brahmā and Viṣṇu could not discover. And, it was here that Pārvatī acquired half of Śiva’s body and as a consequence the Lord became Ardhanārīśvara. Saint Aruṇagirināthar had his vision of Subrahmaṇva here, and became the bard who sang the Tiruppugaḻ. The samādhi of Iḍaikkāṭṭu Siddhar is said to be within the precincts of the great temple of Aruṇāchaleśvara. In our own time Tiruvaṇṇāmalai became the hallowed residence of Śrī Ramaṇa Maharṣi. Once a year on the full-moon day in the month of Kṛttikā, iust at sun-down, a beacon is lit at the top of the sacred hill signifying that Śiva is worshipped at Tiruvaṇṇāmalai in the form of light and fire. This is known as the Dipam festival. Our Āchārya visited the sacred place during this festival in 1929, staying there for about a month, walking round the hill several times, and worshipping at the temple.

The next place of importance to be visited was Aḍaiyapalam near Āraṇi. It was here that the famous Appaya Dīkṣita had lived about four centuries earlier. Dīkṣita was a great Advaitin as well as an ardent Śaiva. He was a polymath who wrote several classical works. The Āchārya reminded the people of Aḍaiyapalam of the great service rendered by Dīkṣita to Advaita and Śaivism, and asked them to observe the birth-anniversary of this eminent teacher and to arrange for popularising his works.

In December 1930, at Tirukkaḻukkunṟam (Pakṣitīrtham), an address of welcome was presented to the Āchārya on behalf of the All-India Sādhu Mahāsaṅgham. The address referred in glowing terms to the invaluable service that the Āchārya was doing to Hindu dharma and society, both through precept and practice, following faithfully the grand tradition of Ādi Śaṅkara. In January 1931, the town of Chingleput had the privilege of receiving the Āchārya — the privilege to which the people of the town had been looking forward for a long time.

A notable event that look place during the Āchārya’s sojourn in Chingleput was the visit of Mr Paul Brunton, a noted British writer, journalist, and spiritual seeker. Mr Brunton was on an extensive tour of India looking out for contacts with mystics, yogins, and spiritual leaders. It was the desire for A Search in Secret India[3] that had brought him to this country from far off England. While in Madras, he met Śrī K. S. Venkataramani, the talented author in English of essays and novels on village life. It was Śrī Venkataramani that took Mr Brunton to Chingleput for an interview with the Āchārya. Through his personal representation to the Āchārya, he succeeded in securing for the English visitor an audience with the Āchārya. The beatific face and the glowing eyes of the Sage produced at once an experience of exaltation in the visiting aspirant. Mr Brunton looked at the Achārya in silence, and was struck with what he saw. Referring to this memorable meeting, he wrote later in his book,

“His noble face, pictured in grey and brown, takes an honoured place in the long portrait gallery of my memory. That elusive element which the French aptly term spirituel is present in his face. His expression is modest and mild, the large dark eyes being extraordinarily tranquil and beautiful. The nose is short, straight and classically regular. There is a rugged little beard on his chin, and the gravity of his mouth is most noticeable. Such a face might have belonged to one of the saints who graced the Christian Church during the Middle Ages, except that this one possesses the added quality of intellectuality. I suppose we of the practical West would say that he has the eyes of a dreamer. Somehow, I feel in an inexplicable way that there is something more than mere dreams behind those heavy lids.”[4]

Mr Brunton put to the Āchārya questions about the world, the improvement of its political and economic conditions, disarmament, etc. In his own characteristic way, the Āchārya probed behind the questions and explained how the inward transformation of man was the pre-condition of a better world.

“If you scrap your battleships and let your cannons rust, that will not stop war. People will continue to fight, even if they have to use sticks!”

“Nothing but spiritual understanding between one nation and another, and between rich and poor, will produce goodwill and thus bring real peace and prosperity”

The Indian attitude towards life and the world, according to the critics, is one of pessimism. But that this view is utterly wrong is borne out by the answer which the Āchārya gave to one of Mr Brunton’s questions.

Mr Brunton:

“Is it your opinion, then, that men are becoming more degraded?”.

The Āchārya:

“No, I do not think so. There is an indwelling divine soul in man which, in the end, must bring him back to God. Do not blame people so much as the environments into which they are born. Their surroundings and circumstances force them to become worse than they really are. That is true of both the East and West. Society must be brought’ into tune with a higher note.”

Mr Brunton does not fail to make a note of the universalistic and catholic vision of the Āchārya. “I am quick to notice,” he writes, “that Shri Shankara does not decry the West in order to exalt the East, as so many in his land do. He admits that each half of the globe possesses its own set of virtues and vices, and that in this way they are roughly equal! He hopes that a wiser generation will fuse the best points of Asiatic and European civilizations into a higher and balanced social scheme.”

Adverting to the purpose for which he had come to India, Mr Brunton asked if the Āchārya would recommend anyone who could serve as his spiritual preceptor, or if the Āchārya himslef would be his guide.

“I am at the head of a public institution”, said the Āchārya,

“a man whose time no longer belongs to himself. My activities demand almost all my time. For years I have spent only three hours in sleep each night. How can I take personal pupils? You must find a master who devotes his time to them,”

It was as directed by the Āchārya that Mr Brunton went to Tiruvaṇṇāmalai and found the Master he had been in quest of, in Śrī Ramaṇa Maharshi. Already a devotee of the Maharshi had told Mr Brunton in Madras about the Sage of Aruṇāchala. Mr Brunton was not keen then, because he thought that the Maharshi might turn out to be another Yogi like the ones he had met earlier in this country. But now, it was different. The Āchārya himself had asked him not to leave South India before he had met the Maharṣi,

After the interview at Chingleput, Mr Brunton returned lo his residence in Madras. That night he saw the Āchārya in a vision. There was a sudden awakening. The room was totally dark. He became conscious of some bright object. He immediately sat up and looked straight at it. This is what he writes:

“My astounded gaze meets the face and form of His Holiness Shri Shankara. It is clearly and unmistakably visible. He does not appear to be some ethereal ghost, but rather a solid human being. There is a mysterious luminosity around the figure which separates it from the surrounding darkness.

“Surely the vision is an impossible one? Have I not left him at Chingleput? I dose my eyes tightly in an effort to test the matter. There is no difference and I still see him quite plainly!

“Let it suffice that 1 receive the sense of a benign and friendly presence. I open my eyes and regard the kindly figure in the loose yellow robe.

The face alters, for the lips smile and seem to say:

“Be humble and then you shall find what you seek!”

“The vision disappears as mysteriously as it has come. It leaves one feeling exalted, happy and unperturbed by its supernormal nature. Shall I dismiss it as a dream? What matters it?"[5]

From Chingleput, the Āchārya went to Kāñchī, the seat of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha. This was his first visit after he had assumed the headship of the Pīṭha. The ceremonial entry into the holy city was made on Sunday the 25th of January, 1931. The city wore a festive appearance that day, the citizens offered to the Āchārya a reverential and enthusiastic welcome. Kāñchī is the city of temples par excellence. The temple of Śrī Kāmākṣī occupies the central place. Ādi Śaṅkara installed the Śrī Chakra in this temple. In the inner prākāra, there is a shrine for Śaṅkara with a life-size image. Tradition has it that he ascended the Sarvajña Pīṭha and attained siddhi in Kāñchī. There are sculptured representations of Śaṅkara in many of the temples including those of Śrī Ekāmreśvara and Śrī Varadarāja. For several centuries past the management of the Kāmākṣī temple was being carried on under the general supervision of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha. In 1840 the Sixty-fourth Āchārya, Śrī Chandraśekharendra Sarasvatī, performed the kumbhābhiṣekam. The very next year, the British Government in India arranged for the taking over of the direct management of the Temple by the Maṭha itself. During our Āchārya’s stay in Kāñchī in 1931, he made arrangements for the renovation of the temple and for the proper and regular conduct of the daily worship.

Leaving Kāñchī towards the end of April 1931, the Āchārya visited Uttiramērūr which is a place of historical importance as there are inscriptions there regarding the ancient democratic institutions. Another great place in Chingleput district to which the Āchārya went was Śrīperumbūdūr, the birth-place of Śrī Rāmānu-jāchāryā. In a discourse which he gave at the Śrī Ādikesava Perumāḷ Temple, he explained the significance of the verse in Puṣpadanta’s Śiva-mahimna-stotra in which the various religious paths are compared to the different rivers joining the same ocean and the differences in approach to God are attributed to the differences in taste.

The chāturmāsya in 1931 was in Chittoor. After that the tour was resumed. While the Āchārya was camping in Āraṇi, a party of about two hundred volunteers of the Indian National Congress wanted to have his darśana . Those were the peak days of the struggle for freedom. The British Government would come down upon anyone who showed any hospitality to the volunteers. Therefore, the officials of the Maṭha were hesitant in the matter of receiving the volunteers. When the Āchārya was informed of the intention of the volunteers, he immediately asked the officials to admit them and arrange for their hospitality. He made individual enquiries of the members of the party and gave to each one of them vibhūti-prasāda.

In March 1932, the Āchārya went to Kālahasti for the Maha-Śiva-rātrī. During his stay there, he walked round the Kailāsa hill, a distance of about thirty miles along difficult forest paths. From Kālahasti, the Āchārya proceeded to Tirupati and Tirumalai; vast concourses of people listened to his daily discourses in chaste Telugu. Among other places in Chittoor District, the Āchārya visited Venkaṭagiri and Nagari. In Nagari, the Āchārya was presiding over a discussion on Vedānta among scholars, one day. The Manager of the Maṭha received a telegram from Kumbhakoṇam carrying the sad news of the passing away of the Āchārya’s Mother on the 14th of June 1932. As the Manager was approaching the Āchārya with the telegram in his hand, the Āchārya enquired if it had come from Kumbhakoṇam, to which the Manager replied ‘Yes’.

The Āchārya made no further enquiry, but asked the Manager to get back. He remained silent for some time,[6] and then asked the assembled scholars:

“What should a sannyāsin do when he hears of the passing away of his mother?”

Guessing what had happened, the scholars were deeply distressed and could not say anything. The Āchārya got up and walked to a water-falls at a distance of two miles followed by a great number of people chanting the Lord’s name. He took his bath, the others too did the same. The passing away of the Mother of the Jagad-guru was felt as a personal loss by everyone of the śiṣyas.

There is a spot of natural beauty near Kagan, called Buggā. In the same temple, here, there are the shrines of Kāśī Viśvanātha and Prayāga Mādhava. A perennial river flows by the temple; and five streams feed the river. Commencing from the 17th of July 1932, the Āchārya observed the chāturmāsya at this fascinating place. During his stay there, the temple was renovated and kumbhābhiṣekam was performed on a grand scale. A large number of devotees from Madras went to Buggā and invited the Āchārya to the Presidency City. En route to Madras the Āchārya visited Tiruttaṇi and the famous Subrahmaṇya shrine there.

Before we follow the Āchārya to Madras, let us record here the epic of a faithful and devoted dog. Since 1927, a dog was following the retinue of the Maṭha. It was a strange dog — an intelligent animal without the least trace of uncleanliness. It would keep watch over the camp during the nights. It would eat only the food given to it from the Maṭha. The Āchārya would therefore enquire every evening if the dog had been fed. When the camp moved from one place to another, the dog would follow, walking underneath the palanquin, and when the entourage stopped so that the devotees of the wayside villages could pay their homage, it would run to a distance and watch devoutly from there, only to rejoin the retinue when it was on the move again. One day, a small boy hit the dog; and the dog was about to retaliate, when the officials of the Maṭha, in fear, caused the dog to be taken to a distance of twenty-five miles blindfolded and left there in a village. But strange as it may seem, the dog returned to where the Āchārya was even before the person who had taken it away could return. From that day onwards the dog would not eat without the Āchārya’s darśana, and stayed till the end of its life with the Maṭha.

The citizens of Madras had the great privilege of receiving the Āchārya on the 28th of September, 1932. During the four months’ stay of the Āchārya in the city, the people felt in their life a visible change for the better. In their crowds they flocked to the camp at the Madras Samskrit College and later in the different parts of the city, and drank deep of the elevating presence and the soul-moving speeches of the Āchārya. On the first night, there was a huge and colourful procession terminating at the Samskrit College. Seated in a decorated palanquin, the Āchārya showered his blessings on the people. Śrī K. Bālasubrahmanya Aiyar and other devotees had made all arrangements for the Āchārya’s stay at the Samskrit College, founded by Śrī Bālasubrahmaṇya Aiyar’s revered father, Justice Śrī V. Krishnaswami Aiyar. A discourse-hall for studying the Śāṅkara-bhāṣya on the Vijayadaśami day was built, for which the Āchārya himself gave the name, Bhāṣya-vijaya-maṇṭapa.

The Corporation of Madras wanted very much to present the Āchārya with an address of welcome. Śrī T. S. Ramaswami Aiyar was then the Mayor. Moving the resolution to present an address, Śrī A. Ramaswami Mudaliyār referred to the fact that that was the first occasion when the Corporation would be presenting an Address to a religious leader, paid his tribute to the Āchārya, saying that he was held in great esteem not only by the Hindus but also by the followers of other religions, and hoped that the resolution would be passed unanimously. The resolution was passed with acclaim by the entire House. But when the invitation was conveyed to the Āchārya, he politely declined as it would not be proper for him to associate himself directly with a secular function at the Corporation Buildings.

The navarātrī in 1932 was celebrated at the Samskrit College. During this pujā-festival, the Āchārya fasts and observes silence on all the nine days. Women are honoured with offerings of gifts, as they are manifestations of Parā Śakti (the Great Mother of the World). And, ceremonial pūjā is performed to girls, commencing with a two-year old on the first day and ending with a ten-year old on the last day. This is what is known as Along with recitation of the Vedas , pārāyaṇam of the Devī-bhāga-vata, the Rāmāyana, the Gītā and other texts, the Chaṇḍī and Śrī-Vidyā homas are performed during the festival. Thousands of people participated in the navarātrī festival at the Samskrit College and received the Āchārya’s benedictions.

After the navarātrī, the Āchārya delivered discourses every evening after the pūjā. Thousands of people listened to these in pin-drop silence. Seated on the siṃhāsana, the Āchārya would remain silent for some- time. Then, slowly he would commence to speak. It was not mere speech; it was a message from the heart, each day. With homely examples, in an engaging manner, he would exhort the audience to lead a clean, simple, unselfish and godly life. The essentials of Hindu dharma , the obligatory duties, the supreme duty of being devoted to God, the harmony of the Hindu cults, the significance of the Hindu festivals and institutions, the cultivation of virtues, and the grandeur of Advaita, formed some of the themes of these discourses.[7] Those who were not able to listen to these speeches had the benefit of reading reports of them every day in “The Hindu” and “The Swadesamitran.” The Āchārya’s teachings enabled the listeners and readers to gain the experience of inward elevation.

During his stay in the city, the Āchārya visitēd some of the educational institutions such as the Ramakrishna Mission Students’ Home, t he P. S., Hindu, and Theological High Schools. He advised both teachers and students to be devoted to the sacred task of educating and learning respectively. Before leaving the city, he blessed some of the eminent scholars and devoted leaders by the award of titles: Mahāmahopādhyāya S. Kuppuswami Sastri received the title Darśana-Kalānidhi, Śrī K. Balasubrahmanya Aiyar, Dharma-rakṣāmaṇi, and Sri A. Krishnaswami Aiyar, Paropakāra-chintāmaṇi.

Tiruvoṟṟivūr near Madras, is a most sacred place. It has been for centuries the favoured resort of mahātmās. The temple of Tvāgeśa and Tripurasundarī is an ancient one. Ādi Śaṅkara installed the Śrī-chakra in this temple. Even to this dav the archakas that officiate at the shrine of Tripurasundarī are Nambūdiris. There is an image of Śaṅkara in the inner prākāra of the temple. Several of the heads of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha chose to live at least for some time at Tiruvoṟṟyūr. In the Śaṅkara Maṭha there, the adhiṣṭhānas of two Āchāryas of the Kāmakoṭi Pītha are to be seen. Our Āchārya visited Tiruvoṟṟyūr and made the holy place holier.

Leaving Madras, the Āchārya went to the South a sain in order to participate in the Mahāmakham festival at Kurabhakoṇam in March 1933. Since the vijayā-yātrā was still in progress, he did not enter the Maṭha at Kumbhakoṇam; the camp was set up in Tiruviḍaimarudūr. From there, he went to Kumbhakoṇam on the festival day and took the ceremonial bath in the Tank. About six lakhs of people thronged to Kumbhakoṇam that dav to oarticimte in the festival that comes once in twelve years. After the Mahāmakham the Āchārya continued to stay for some months at the Śaṅkara Maṭha in Tiruviḍaimarudūr. According to tradition, when Ādi Śaṅkara visited this holy place and had darśana of Śrī Mahāliṅga-svāmī in the temple, there appeared Śiva’s form from the Liṅga, raised the right hand declared three times that “Advaita alone is the truth”, and disappeared. In 1933, our Āchārya celebrated the Śaṅkara Jayantī at Tiruviḍaimarudūr.

For a long time the Āchārya had had the intention of visiting Chidambaram. But. for over two hundred years no previous Āchārya had gone there, the reason being that the Dīkṣitars of the Temple of Śrī Naṭarāja would not let even the Āchāryas of the Śaṅkara Maṭha take the sacred ashes straight from the cup as was the custom in all other temples as a mark of respect shown to the Pīṭha. Many of the devotees of Chidambaram, however, wished very much that the Āchārya should visit Chidambaram; and the Āchārya too wanted to have Śrī Naṭarāja’s darśana. Accepting the invitation of the devotees, he arrived at Chidambaram on May 18, 1933. A great reception was accorded to him by the inhabitants of Chidambaram including the Dīkṣitars. The devotees of the Āchārya were rather apprehensive of what might happen when the Āchārya visited the temple in regard to the offering of vibhūti. The Āchārya, however, was utterly unconcerned. All that he wanted was to have Śrī Naṭarāja’s darśana as early as possible. He resolved to go to the temple early In the morning: having asked one of his personal attendants to wait for him at the tank, he went there alone at 4 a.m., had his bath and anusṭhāna, and when the shrine was opened he entered and stood in the presence of Śrī Naṭarāja absorbed in contemplation. The Dīkṣitar who was offering the morning worship was taken aback when he saw the Āchārya there. He sent word to the other Dīkṣitars; and all of them came at once. They submitted to the Āchārya that they were planning for a ceremonial reception, and that they were pained at the fact that none of them were present in the temple to receive him that morning. The Āchārya consoled them saying that he had gone to the temple to have the early morning darśana of Śrī Naṭarāja, known as the viśva-rūpa.-darśana, and that he would be visiting the temple several times during his sojourn in Chidambaram. The Dīkṣitars honoured the Āchārya in the same manner as he is honoured in the other temples. And, at the earnest request of the Dīkṣitars, the Āchārya stayed in the temple for a few days and performed the Śrī Chandramaulīśvara-pūjā in the thousand-pillared Maṇṭapa. The devotees had the unique experience of witnessing pūjā performed, at the same place, to two of the five Sphaṭika-liṅgas brought by Śaṅkara, according to tradition, from Kailāsa—the Mokṣa-Liṅga of Chidambaram and the Yoga-Liṅga of Śrī Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha.

The 1933 chāturmāsya and navrātrī were observed at Tañjāvūr. A Śaṅkara Maṭha was established there mainly through the munificence of the Tañjāvūr Junior Prince Pratapa Simha Raja and Śrī T. R. Joshi. The preparation for the Āchārya’s northward journey to Kāśī had by now been completed. A number of years earlier the Āchārya had commissioned a youth Śrī Ananta-krishna Śarmā to go to Kāśī on foot. He had to walk the entire distance and send notes regarding the route and places en route. He should learn Hindi before he returned and could do the return journey by rail. Śrī Anantakrishna Śarmā carried out the instructions in the letter and in spirit. It took six months for him to reach Kāśī. Aged sannyāsins like Brahmānanda Sarasvatī and revered scholars including Mahāmahopādhyāya Ānanda Saran and Pratap Sītaram Sastri, Agent of the Sringeri Maṭha, sent their letter of invitation to the Āchārya of the Kāmakoṭi Pīṭha on behalf of the citizens of Vārāṇasī; Mahāmahopādhyāya Chinnanaswami Sāstrī, Professor of Mīmāṃsā in the Banaras Hindu University, read out the letter of invitation in the Chidambaram camp of His Holiness.

A representative Committee had been formed at Vārāṇasī headed by His Highness the Mahārājā of Kāśī, with Pandit Madanmohan Malaviya, the Mahāmahopādhyāyas, distinguished Scholars, and other eminent men as members. The citizens of the Spiritual Capital of our country were eagerly looking forward to the visit of our Āchārya, who had already made the saṅkalpa for kāśīyātrā.

In conformity with the past practice observed by the previous Government, the Government of Madras issued a notification to the Governments of other States, and the native States to accord due honour and all facilities to the Āchārya and his entourage during his journey to Kāśī.

The journey commenced in the second week of September 1933. The Āchārya proceeded northwards, covering about twenty miles each day. While camping at Kurnool, the Āchārya thought of going to Śrī-śaila which is regarded as the Southern Kailāsa. Here, the Lord Śiva appears as Mallikārjuna-liṅga, and Parvatī as Bhramarāmbikā. The Liṅga is one of the twelve Jyotir-Liṅgas in the country. The holy place is counted among the eighteen Śakti-pīthas. The sthala-vṛkṣa is the Arjuna tree. (The two other sacred places which have the Arjuna as the sthala-vṛkṣa, are Tiruviḍaimarudūr, also known as Madhyārjuna in Tañjāvūr District, and Tiruppuḍaimarudūr, also called Puṭārjuna in Tirunelveli District). The tīrtha at Śrī-Śaila is Pātāla-gaṅgā (the counterpart of Ākāśa-gaṅgā at Tirumalai). Ādi Śaṅkara has sung the praise of Śrī Mallikārjuna in his Śivānanda-laharī.

Our Āchārya delights in reciting these verses—especially the 50th verse:

“I adore Mallikārjuna, the great Liṅga at Śrī-Śaila (the Arjuna tree entwined by jasmine creepers on the beautiful mountain) who is embraced by Pārvatī (which is auspicious), who dances wonderfully at dusk (which blooms profusely in the evening), who is established through Vedānta (whose flowers are placed on one’s ears and head), who is pleasing with the loving Bhramarāmbikā by His side (which is grand with eager honeybees humming around), who shines in the repeated contemplations of pious people (which always wafts good scent), who wears serpents as ornaments (which embellishes those who seek enjoyment), who is worshipped by all the gods (which is the best of flower-trees), and who expresses virtue (and. which is well-known for its high quality)”.[8]

Taking with him only a few attendants, the Āchārya went by boat upto Peddacheruvu, and from there walked the remaining distance of eleven miles uphill. He reached Śrī-śaila on the 29th of January 1934, went to the temple, and stood before the Deities for a long time reciting verses from the Śivānandalaharī and the Saundarya-laharī. After spending a few days at Śrī-śaila, the Āchārya returned to Kurnool. During the difficult Śrī-śaila journey through dense forests, the Chenchus, members of a wild hill-tribe, gave every assistance and protection to the visiting party. They considered the Āchārya’s presence in their midst a great blessing.

Crossing the Tuṅgabhadrā at Kurnool, the Āchārya entered the Hyderabad State. He reached the Capital of the State on the 12th of February 1934. The people and the State officials including the Chief Minister vied with one another in paying their homage to the Jagadguru. At the command of the Nizam, the State Government undertook to meet one day’s expenses of the Maṭha. Every facility was provided for the conduct of the daily pūjā, etc. During the Āchārya’s stay in Hyderabad a Sanātana-dharmasabhā was held; it was attended by many prominent scholars. In his inaugural address to the Sabhā, the Āchārya emphasized the need for safeguarding the Dharma, reminded the Hindus of their duty to follow the rules of conduct, and asked the people to hold the paṇḍitas in high esteem.

As the journey from Hyderabad northwards would be a difficult one—through wild forests and uninhabited areas—a large part of the entourage consisting of carts, cattle, attendants and others, was left behind; this part rejoined the group that accompanied the Āchārya, after four years, in Andhra Pradesa. Leaving Secunderabad on the 24th of April 1934, the Āchārya reached a place called Soṇṇā on the banks of the Godāvarī on the 5th of May, and had his bath in the sacred river.

What was then known as the Central Provinces was the part of India which lay next in the Āchāryas itenerary. In May that year, Śrī Śaṅkara Jayantī was celebrated at Bendelvāḍā on the banks of a tributary of the Godāvarī. After spending a few days at Nagpur in June, the Āchārya travelled through the country of the Vindhya mountains. It was an arduous journey in burning summer, through practically waterless tracts. The members of the party braved all difficulties with cheer, their sole aim being to serve the Master in the fulfilment of the resolve to complete the pilgrimage to Kāśī. After crossing the Vindhyas, the Āchārya reached Jabalpur on the 3rd of July 1934, and had his bath in the sacred river Narmadā. Journeying quickly thereafter, the Āchārya arrived at Prayāga (Allahabad) on the 23rd of July 1934. At the outskirts of the holy city, the prominent leaders of the place headed by Mahāmahopādhyāya Gaṅgānātha Jhā received the Āchārya with due ceremony. Thousands of people lined the route of the procession, uttering the words “Victory to the great Guru!” (Gurumahārāj-ji-ki Jai!).

On the 25th of July 1934, the Āchārya immersed the sacred sand he had brought from Rāmeśvaram in the holy waters at Prayāga, the place of Triveṇī-saṅgama, the confluence of the Gaṅgā, the Yamunā, and the subterranean Sarasvatī; and gathering the holy water in vessels, he had it sent to the places of pilgrimage in South India. By these significant ceremonial acts, the Āchārya made it known to our people how custom and tradition are expressive of the spiritual, as well as geographical, unity of India. On the 26th of July, the Āchārya commenced the chāturmāsya at Prayāga. For the Vyāsa-pūjā that day, many devotees assembled there from the different parts of the country. During this chāturmāsya period, a conference of scholars was held in the immediate presence of the Āchārya. Several paṇḍitas of North India participated in the deliberations of the Conference, and received the Āchārya’s blessings.

From Prayāga (Allahabad) to Kāśī—a distance of eighty miles—the Āchārya travelled by foot. He entered the most holy city of Kāśī on the 6th of October 1934, and was received by the citizens in their thousands, headed by the Mahārājā of Kāśī, Pandit Madanmohan Malaviya, and others. About a lakh of people participated in the procession that day, many of them uttering the full-throated cries of victory, “Jagadguru-Mahārāj-ji-ki Jai!” Unprecedented crowds—a record in the history of the city-gathered to greet the visiting Āchārya. A glowing account of Kāśī’s reception to the Āchārya was published in the Hindi newspaper “Pandit” dated the 8th of October 1934. Among other things, it said that the joy of the people knew no bounds when they beheld the beaming face of the great ascetic, and that the procession and the mammoth meeting were unprecedented in magnificence and splendour iti the history of the holy city within memory.

Kāśī, the city of the Lord Viśvanātha and Śrī Viśālākṣī, is considered to be one of the seven mokṣa-puris. The holy Gaṅgā flows here in a northward direction, and in the form of a crescent. The city is the resort of saints and scholars. Kāśī is also known as Vāraṇāsī, because it lies between two tributary rivers Vāraṇa and Asi. It was in this city near the Maṇikarṇikā Ghaṭṭa that Ādi Śaṅkara wrote his commentaries. It was Kāśī that proclaimed him as the Jagad-guru. It was from there that he started on his dig-vijaya. And so, our Āchārya’s visit to Kāśī was full of supreme significance. On the very day of his arrival there, the Āchārya had darśana of the Lord Viśvanātha and Śrī Annapūrṇā. On the 7th of October, after a bath in the Gaṅgā at the Maṇikarṇikā Ghaṭṭa, he performed the Chandramaulīśvara-pūjā in the Lord’s temple itself. From the 9th of October onwards, the navarātrī festival was celebrated. On the Vijaya-daśmī day, the Āchārya visited the Dakṣiṇāmūrtī Maṭha on the other bank of the Gaṅgā. On the 9th of February 1935, in response to Pandit Madanmohan Malaviya’s request the Āchārya paid a visit to the Hindu University. In his welcome address consisting of five verses in Samskrit, Pandit Malaviya referred to the fact that the Āchārya was adorning the Kāñchī-pīṭha established by Śrī Śaṅkara, and that his fame and grace born of his great wisdom, austerity, compassion, generosity, etc., had spread far and wide in this sacred land, and requested His Holiness to bless the assembled University community by his words of advice. Addressing the teachers and students in felicitous Samskrit, the Āchārya pointed out that the end of education is to gain peace of mind, and that it is by acquiring wisdom that one realizes immortality. Commending the laudable efforts of Pandit Malaviya in founding the Hindu University, the Āchārya said that the main objective of āstika education should always be kept in view in the details regarding the courses of study, etc., and expressed the wish that the University should train and send out leaders of thought and action who would set an example in ideal living for the masses of the people to follow. In his concluding speech, Pandit Malaviya said that while from the legends regarding Ādi Śaṅkara they knew that the great Master visited Kāśī and saved the world through his wondrous works, they now had the rare experience of seeing with their own eyes in Kāśī the Āchārya who was an avatāra of Ādi Śaṅkara.