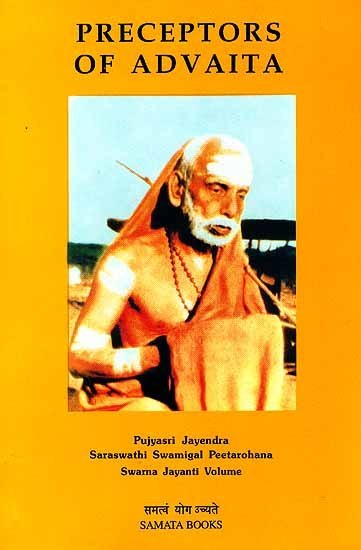

Preceptors of Advaita

by T. M. P. Mahadevan | 1968 | 179,170 words | ISBN-13: 9788185208510

The Advaita tradition traces its inspiration to God Himself — as Śrīman-Nārāyaṇa or as Sadā-Śiva. The supreme Lord revealed the wisdom of Advaita to Brahma, the Creator, who in turn imparted it to Vasiṣṭha....

28. Śaṅkarānanda

SANKARANANDA

by

P. C. Subbamma

M. A., M. LITT.

As is common with the lives of our great men in the past, as regards Śaṅkarānanda also it is difficult to determine with any accuracy his date and to gather the details of his life. Yet from his writings it is possible to gather that Śaṅkarānanda was the disciple of Anantātman and Vidyātīrtha. Śaṅkarānanda along with Bhāratītīrtha, and Vidyāraṇya, studied under Vidyātīrtha. He became a guru of Vidyāraṇya. Vidyāraṇya offers his salutations to his guru thus:

‘namaḥ śrī śaṅkarānanda-guru-pādāṃbujanmane’

Śaṅkarānanda’s most important work is Ātmapurāṇa which is also known as Upaniṣad-ratna and contains the essence of the Upaniṣads in verse in the form of story and dialogue. He has also written a commentary on the Bhagavad-gīta and a vṛtti on Brahma-sūtra. Besides, he has written Dīpikās on several major and minor Upaniṣads. Not only this, but there are other independent works attributed to Śaṅkarānanda. For instance— Yatya-nuṣṭhāna-paddhati, Vivekasāra, Śruti-tātparya-nirṇaya, and so on. His magnum opus, however, is Ātmapurāṇa.

We shall now set forth briefly the teachings of the Ātmapurāṇa.

Śaṅkarānanda is mainly concerned with explaining the nature of Ātman; yet in order to generate in the nninds of aspirants an irresistible attraction towards the knowledge of Brahman, he introduces several stories from the major as well as the minor Upaniṣads. Most of the materials are drawn from Śrī Śaṅkara’s commentary on the Upaniṣads.

Brahman or Ātman, not being conditioned by the three divisions, namely space, time, and matter, is homogeneous. The limitations that are caused by the above three factors exist only in the objects comprising the not-self.

(1) The counter-correlate of the absolute non-existence (atyantābhāva pratiyogī) is called space-division (deśa-pariccheda). This division is seen in a pot which exists in one place while there is the absence of that pot in other places, since the counter-correlateness (pratiyogī) of the absolute non-existence is in that existent pot.

(2) The counter-correlate of the prior non-existence and of the posterior non-existence is known as the time division. This division is applied to the halves of a pot, since there are both the prior non-existence (prāgabhāva) and posterior non-existence (pradhvaṃsābhāva) in a pot before its production and after its destruction, respectively.

(3) The countercorrelate of mutual non-existence (anyonyābhāva) is called the division of matter. For instance, a cloth is not a pot and vice versa. In this cognition, the non-existence of the cloth in the pot and the non-existence of the pot in the cloth is understood.

Thus all the objects that come under the category of not-self are conditioned by three kinds of limitations. Brahman, being all-pervading, transcends the division of space. Since Brahman is eternal, the category of time is inapplicable to it. And Brahman, being the inmost self of all, is not conditioned by matter. So, Brahman is established as the transcendental Reality beyond all kinds of divisions.

The Self (Ātman) does not come within the range of mind and speech. Every word employed to denote an object, denotes that object in relation to a genus, or a quality, or an action. For instance, the word ‘pot’ denotes a thing which contains a particular form, or a quality, blue, etc; the word ‘cook’ denotes a man who is associated with the act of cooking. The Self (Ātman) does not have a genus; it is not related to any quality; it does not act. So, words cannot primarily convey Ātman. However, Brahman-Ātman is taught by the method of adhyāropa and apavāda , which consists in first super-imposing the world on Brahman-Ātman and negating it subsequently. In this teaching of Brahman-Ātman, exciusive-cum-non-exclusive implication (jahad-ajahallakṣaṇa) is resorted to.

Is the universe which we perceive self-sustaining and self-established? The Upaniṣads affirm that there is a Being transcending the universe and yet immanent in it. And that Being is Brahman, which is non-dual. This non-dual Brahman appears as the universe, and avidyā or māyā is the cause of the appearance of Brahman as the universe. This avidyā is doubly evil in that it veils the true nature of Brahman and distorts it in the form of Īśvara, jīva and the jagat. Brahman is said to be the source of the universe in that it is the substratum of avidyā, which is the immediate cause of the universe. Avidyā, being inspired by the reflection of Brahman in it, transforms itself into the form of the universe. It is thus the transformative material cause (paṛṇāmyupādāna) of the universe. Brahman only illusorily appears as the universe; it is the transfigurative material cause (vivarto’pādāna) of the universe. Brahman viewed in this aspect is Īśvara. While the Nyāya system holds that atoms are the material cause of the universe and God is the efficient cause, Advaita holds that Brahman as Īśvara is both the material and the efficient cause of the universe.

It is because of its association with avidyā and its product, intellect, that Brahman, which is supra-relational (asaṅga), appears as the individual soul. The latter in essence is Brahman. But, owing to avidyā, it identifies itself with intellect and its qualities, experiences pleasure, pain, etc., and undergoes transmigration. It is the mind alone that acts and thinks; but being falsely identified with mind, Ātman, which is pure consciousness, appears to act and think. Avidyā, thus, is the source of all evil. It is described as the one which is capable of bringing together two incompatible things (aghaṭita-ghaṭanā-paṭīyasī-māyā). Avidyā is termed ajñāna, mūlaprakṛti, pradhāna, and avyākṛta. This avidyā is the cause of the superimposition of all the objects on Brahman or Ātman. It becomes operative in this way only by being itself superimposed on Brahman. It does not require another avidyā for its own superimposition on Ātman; for, to assume a second avidyā is to be involved in the fallacy of infinite regress. Hence it is admitted that avidyā itself is the cause of its superimposition on Ātman.

Avidyā, the root-cause of the universe, is one; yet it consists of various aspects, and these are known as tūlājñāna or tūlāvidyā. Avidyā which is present in Ātman and which is annihilated by the intuitive knowledge of Ātman is known as mūlāvidyā. And the various aspects of avidyā which are present in the consciousness delimited by the objects and which, are removed by the knowledge of the true nature of those objects are termed tūlāvidyā.

The entire universe is superimposed on Ātman through avidyā. The Upaniṣadie text ‘neti neti’ negates the entire universe superimposed on Ātman, and Ātman the self-existent entity alone remains. The individual souls are identical with Ātman. But, owing to avidyā, they have lost sight of their identity with Ātman and undergo transmigration. By pursuing Vedāntic study, reflection, and meditation, an individual soul attains to the intuitive knowledge of Brahman. Avidyā, in his case, is annihilated and the individual soul becomes free from characteristics such as finitude, agency, etc., that are brought about by avidyā. He is a released soul and he remains as Brahman.